A Comprehensive Fluorescence Microscopy Protocol for Quantitative Analysis of Nuclear Fragmentation

This article provides a detailed guide for researchers and drug development professionals on employing fluorescence microscopy to detect and quantify nuclear fragmentation, a key hallmark of cellular processes like apoptosis.

A Comprehensive Fluorescence Microscopy Protocol for Quantitative Analysis of Nuclear Fragmentation

Abstract

This article provides a detailed guide for researchers and drug development professionals on employing fluorescence microscopy to detect and quantify nuclear fragmentation, a key hallmark of cellular processes like apoptosis. It covers foundational principles of nuclear staining, a step-by-step methodological protocol for reliable imaging, advanced troubleshooting for common pitfalls such as background fluorescence and photobleaching, and rigorous validation techniques to ensure data accuracy. By integrating traditional methods with emerging computational and super-resolution approaches, this protocol aims to standardize nuclear fragmentation analysis, enhancing reproducibility and insight in biomedical research.

Understanding Nuclear Fragmentation: Principles and Staining Strategies

Nuclear Fragmentation as a Biomarker in Apoptosis and Disease

Nuclear fragmentation stands as a definitive morphological hallmark of apoptotic cell death. Its quantification provides researchers and drug development professionals with a powerful biomarker for assessing genotoxic stress, chemical toxicity, and therapeutic efficacy. Within the context of fluorescence microscopy research, this application note details standardized protocols for detecting and quantifying nuclear fragmentation, summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies, illustrates the core molecular pathways, and provides essential reagent solutions for robust experimental implementation.

Quantitative Characterization of Nuclear Fragmentation

Nuclear fragmentation manifests through distinct, quantifiable cellular and molecular changes. The following tables consolidate key quantitative data from recent studies for easy reference and experimental comparison.

Table 1: Quantifiable Nuclear Abnormalities and Associated Gene Expression Changes

This table summarizes the concentration- and time-dependent genotoxic effects observed in zebrafish models exposed to lead (Pb) and chromium (Cr), as assessed by erythrocytic nuclear abnormalities (ENA) assay and gene expression analysis [1].

| Parameter | Exposure Conditions | Quantitative Findings | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erythrocytic Nuclear Abnormalities (ENA) | Pb (2.5-10 ppb); Cr (0.5-2 ppm); 15-60 days | Concentration- and time-dependent increase; highest frequency in Pb+Cr combined exposure | Indicator of severe chromosomal damage and genotoxicity [1]. |

| DNA Fragmentation | Pb and Cr, individual and combined | Significant fragmentation confirmed via agarose gel electrophoresis, particularly in liver and gut tissues | Direct evidence of DNA strand breaks and genomic instability [1]. |

| Pro-apoptotic Gene Upregulation (p53, bax, caspase-3, caspase-9) | Pb and Cr, individual and combined | Significant upregulation measured by qRT-PCR | Molecular trigger for apoptosis execution; indicates activation of intrinsic apoptotic pathway [1]. |

| Anti-apoptotic Gene Downregulation (bcl-2) | Pb and Cr, individual and combined | Significant downregulation measured by qRT-PCR | Removal of suppression on apoptosis, enhancing cellular suicidal response [1]. |

Table 2: Spectrofluorometric and 3D Morphological Metrics in Cell Models

This table outlines quantitative parameters for detecting nuclear condensation and fragmentation in human cell lines using spectrofluorometry and 3D morphological analysis [2] [3].

| Method / Assay | Cell Model / Treatment | Key Quantitative Metrics | Protocol Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hoechst 33258 Spectrofluorometry | HepG2 & HK-2 cells; Cisplatin, Staurosporine, Camptothecin | Increase in fluorescence intensity (RFU) at Ex/Em = 352/461 nm; Dose- and time-dependent signal increase | H33258 at 2 µg/mL; 5 min incubation; Centrifugation (5 min, 8000g) post-treatment is critical [2]. |

| 3D Confocal Morphological Analysis | MCF-7 cells; Doxorubicin-induced apoptosis | Quantification of cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, and nuclear fragmentation via 3D reconstruction of image stacks | Staining with Syto-61 (nucleus), Mito-Tracker Orange, Annexin V (apoptosis detection); 63x oil immersion objective [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Fluorescence-Based Detection

Protocol: Spectrofluorometric Quantification of Nuclear Condensation

This protocol, adapted for a 96-well plate format, enables high-throughput, quantitative assessment of nuclear changes in intact cells [2].

Principle: The binding of the cell-permeant Hoechst 33258 dye to A/T-rich regions of DNA results in a significant increase in fluorescence intensity. Apoptotic cells with condensed and fragmented chromatin exhibit enhanced fluorescence, which can be quantitatively measured.

Materials:

- Cell line of interest (e.g., HepG2, HK-2)

- Apoptotic inducer (e.g., Cisplatin, Staurosporine, Camptothecin)

- Hoechst 33258 stock solution

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS)

- 96-well microplate suitable for fluorescence reading

- Centrifuge with a microplate rotor

- Fluorescence microplate reader

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding and Treatment: Seed cells in a 96-well plate and allow to adhere. Treat with the test compound or apoptotic inducer for the desired duration.

- Preparation: After treatment, centrifuge the entire 96-well plate at 8000 x g for 5 minutes at room temperature to ensure cell sedimentation.

- Medium Replacement: Carefully aspirate 70 µL of the culture medium from each well and replace it with 70 µL of PBS.

- Staining: Add Hoechst 33258 solution directly to each well to achieve a final working concentration of 2 µg/mL. Mix gently.

- Incubation and Reading: Incubate the plate for 5 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Immediately measure the fluorescence intensity using excitation/emission wavelengths of 352/461 nm.

- Data Analysis: Subtract the background fluorescence (from wells without cells) and express the results in Relative Fluorescence Units (RFU). A statistically significant increase in RFU compared to the untreated control indicates nuclear condensation and fragmentation.

Protocol: Fluorescence Microscopy Assay for Erythrocytic Nuclear Abnormalities (ENA)

This protocol is used for in vivo genotoxicity assessment in zebrafish models, but the staining principles are widely applicable [1].

Principle: Nucleated erythrocytes from fish are stained and scored for specific nuclear anomalies, which are sensitive indicators of chromosomal damage induced by genotoxic agents.

Materials:

- Blood smears from control and exposed organisms (e.g., zebrafish)

- Fluorescent DNA-binding dye (e.g., Acridine Orange, DAPI, or Syto-61)

- Microscope slides, coverslips, and mounting medium

- Fluorescence microscope with appropriate filter sets

Procedure:

- Smear Preparation: Prepare thin blood smears on clean microscope slides and allow them to air dry.

- Fixation: Fix the cells according to the standard protocol for the chosen dye.

- Staining: Stain the fixed smears with the fluorescent DNA-binding dye. For example, incubate with Syto-61 at 1 µM for 30 minutes [3].

- Mounting and Visualization: Rinse the slide, mount with a coverslip, and visualize under a fluorescence microscope using a 60x or 100x oil-immersion objective.

- Scoring and Analysis: Systematically score a sufficient number of cells (e.g., 1000 cells per sample) for the presence of micronuclei and other nuclear abnormalities such as blebbed, lobed, and notched nuclei. The frequency of ENAs is expressed as a percentage of the total cells scored.

Signaling Pathways and Nuclear Expulsion Mechanisms

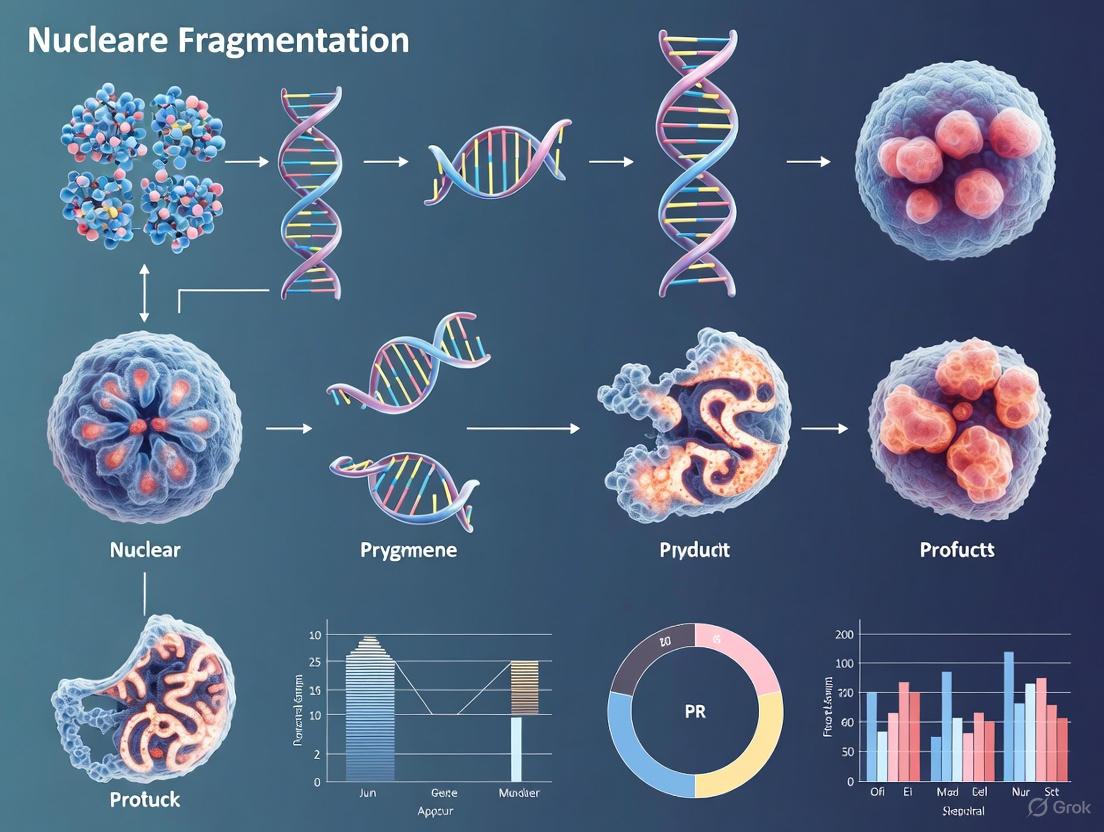

Advanced research has elucidated a specific pathway of apoptosis-induced nuclear expulsion, a process distinct from classic nuclear fragmentation, with significant implications in cancer metastasis [4]. The following diagram illustrates this pathway and its key triggers.

Diagram 1: The pathway of Padi4-dependent nuclear expulsion in cancer cells. This process is triggered by apoptosis inducers that cause calcium influx and caspase activation, leading to Padi4-mediated histone citrullination, nuclear expulsion, and the release of Nuclear Expulsion Products (NEPs). Chromatin-bound S100a4 in NEPs activates the RAGE receptor on surviving tumor cells, promoting metastatic outgrowth. This pathway can be blocked by Padi4 inhibition or knockout [4].

Beyond the novel nuclear expulsion pathway, the intrinsic apoptotic pathway is a primary driver of nuclear fragmentation. The following diagram details the key molecular events linking genotoxic stress to nuclear disintegration.

Diagram 2: The intrinsic apoptotic pathway leading to nuclear fragmentation. Genotoxic stress from agents like lead and chromium induces DNA damage and oxidative stress, triggering a cascade involving p53 upregulation, a shift in the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio, caspase activation, and the eventual cleavage of DNA by activated nucleases like CAD/DFF, resulting in the hallmark nuclear morphology of apoptosis [1] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs essential reagents and their applications for studying nuclear fragmentation and apoptosis.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Nuclear Fragmentation Research

| Reagent / Assay | Function and Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Hoechst 33258 | Cell-permeant DNA dye for spectrofluorometric quantification of nuclear condensation/fragmentation and fluorescence microscopy [2]. | Optimal at 2 µg/mL; requires centrifugation for repeatable results; binds preferentially to A/T-rich DNA. |

| Syto-61 | Cell-permeant nucleic acid stain for nuclear visualization in confocal microscopy and 3D morphological analysis [3]. | Quantum yield increases upon binding nucleic acids; suitable for multi-color staining protocols. |

| Annexin V Conjugates | Binds to phosphatidylserine (PS) exposed on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane in early apoptosis [3]. | Used in conjunction with viability dyes (e.g., PI) to distinguish early apoptotic from late apoptotic/necrotic cells. |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) | Membrane-impermeant DNA dye for flow cytometric cell cycle analysis and identification of dead/late apoptotic cells [5]. | Requires cell fixation or permeabilization; must be used with RNase to avoid RNA binding. |

| Caspase Inhibitors (e.g., Z-LEHD-FMK, Q-VD-OPh) | Specific inhibitors to probe the role of caspases in the apoptotic pathway and nuclear expulsion [4]. | Useful for establishing the causal role of caspases in the observed nuclear morphology. |

| Padi4 Inhibitor (GSK-484) | Inhibits the enzymatic activity of Padi4, blocking histone citrullination and subsequent nuclear expulsion [4]. | Critical tool for investigating the novel nuclear expulsion pathway in metastatic outgrowth. |

Fluorescent nuclear stains are indispensable tools in cell biology, with DAPI and Hoechst dyes representing two of the most prominent examples for visualizing DNA in fluorescence microscopy. Their specific binding mechanism to adenine-thymine (A-T) rich regions makes them particularly valuable for nuclear fragmentation research, a critical area in studying apoptosis and genomic instability. This application note details the molecular mechanism of action of these dyes, provides quantitative binding data, and outlines detailed protocols for their use in fixed and live-cell imaging. Understanding their precise interaction with DNA is fundamental for designing robust experimental frameworks in drug development research, where accurate assessment of nuclear morphology and DNA content is paramount.

Molecular Mechanism of Action

Minor Groove Binding and Fluorescence Enhancement

DAPI and Hoechst dyes belong to a class of fluorescent probes known as minor-groove binders. Their mechanism of action is characterized by a highly specific non-covalent interaction with the DNA double helix. Both dyes exhibit a strong preference for binding to the minor groove of double-stranded DNA, particularly in regions that are rich in consecutive adenine-thymine (A-T) base pairs [6] [7]. The molecular architecture of the minor groove in A-T rich sequences provides an optimal steric and chemical environment for these planar, crescent-shaped molecules to dock securely.

A key feature of their binding is the substantial enhancement of fluorescence upon DNA association. In their unbound state, these dyes demonstrate minimal fluorescence; however, once bound within the DNA minor groove, their rotational freedom is restricted, and hydration is reduced, leading to a dramatic increase in quantum yield [8]. This suppression of non-radiative relaxation pathways results in a 20 to 30-fold increase in fluorescence intensity, providing a high signal-to-noise ratio for microscopic detection [9] [8]. This property is crucial for sensitive detection in nuclear fragmentation studies, where visualizing subtle changes in DNA integrity is essential.

Structural Basis for A-T Rich Specificity

The molecular specificity for A-T tracts arises from the formation of specific hydrogen bonds between the amidino groups of the dyes and the hydrogen bond acceptors (N3 of adenine and O2 of thymine) located on the floor of the minor groove in B-form DNA [10]. Furthermore, the van der Waals contacts between the aromatic rings of the dyes and the walls of the minor groove provide additional binding energy. This interaction network is geometrically favored in A-T rich sequences, where the minor groove is narrower and deeper compared to G-C rich regions, creating a more complementary binding pocket for the dyes [10].

Table 1: Spectral Properties of DAPI and Hoechst Dyes

| Dye Name | Excitation Maximum (nm) | Emission Maximum (nm) | Fluorescence Enhancement Upon DNA Binding | Binding Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAPI | 358 | 461 | ~20-fold [9] | A-T rich minor groove [7] |

| Hoechst 33258 | 352 | 461 | ~30-fold [8] | A-T rich minor groove [10] |

| Hoechst 33342 | 350 | 461 | ~30-fold [8] | A-T rich minor groove [6] |

Quantitative Binding Analysis

Binding Affinity and Sequence Preference

The binding affinity of DAPI and Hoechst dyes is not uniform across all A-T rich sequences. Detailed kinetic and equilibrium studies using defined DNA hairpins have revealed a hierarchy of binding preferences. The association constants can vary by orders of magnitude depending on the specific sequence context, which has profound implications for the uniformity of nuclear staining [10].

Research by Breusegem et al. demonstrated that for Hoechst 33258, the association constant (K_a) for the AATT site was exceptionally high at approximately 5.5 x 10^8 M^-1, making it the preferred binding site. The affinity decreased in the order: AATT >> TAAT ≈ ATAT > TATA ≈ TTAA [10]. The extreme values of K_a differed by a factor of 200 for Hoechst 33258, highlighting a significant sequence dependency. DAPI, while following a similar preference pattern, exhibited a smaller dynamic range in affinity (a factor of 30), suggesting a somewhat broader sequence tolerance [10]. This quantitative data is critical for interpreting staining patterns, especially in heterochromatic regions which may have varying local sequence compositions.

Binding Kinetics

The binding process is characterized by nearly diffusion-controlled association rates, while dissociation rates vary significantly with sequence, thereby controlling the overall affinity [10]. For the high-affinity AATT site, Hoechst 33258 exhibits a slow dissociation rate (k_d = 0.42 s^-1), contributing to stable staining necessary for prolonged imaging sessions. In contrast, for lower-affinity sites like TTAA, the dissociation rate is much faster (k_d = 96 s^-1) [10]. High-resolution kinetic studies have also revealed that binding to the highest-affinity sites can involve a multi-step mechanism or the formation of more than one distinct high-affinity complex, adding a layer of complexity to the interpretation of fluorescence signals [10].

Table 2: Quantitative Binding Parameters for Different DNA Sequences [10]

| DNA Sequence Site | Relative Affinity (Hoechst 33258) | Relative Affinity (DAPI) | Dissociation Rate Constant, k_d (s^-1) for Hoechst 33258 |

|---|---|---|---|

| AATT | Highest | Highest | 0.42 |

| TAAT | Medium | Medium | Not Specified |

| ATAT | Medium | Medium | Not Specified |

| TATA | Low | Low | Not Specified |

| TTAA | Lowest | Low | 96 |

Advanced Imaging Applications

Super-Resolution Microscopy

The utility of DAPI and Hoechst extends beyond conventional fluorescence microscopy into super-resolution techniques. Both dyes can undergo UV-induced photoconversion, where illumination with 405 nm light causes a subset of the blue-emitting molecules to stochastically transition to a green-emitting form [11]. This property can be harnessed for Single Molecule Localization Microscopy (SMLM), such as Spectral Position Determination Microscopy (SPDM) or dSTORM. In these modalities, the photoconverted molecules are excited with a 491 nm laser, and their individual positions are recorded with a localization precision of 15–25 nm, enabling the reconstruction of high-resolution DNA density maps [11]. This is particularly powerful for studying nuclear fragmentation at the nanoscale, revealing details of chromatin organization and breakage sites that are obscured by the diffraction limit in conventional microscopy.

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM)

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM) presents another advanced application. The fluorescence lifetime of DNA-bound dyes is sensitive to the local refractive index, which in turn is influenced by DNA compaction density [12]. Loosely packed euchromatin (often gene-rich) and densely packed heterochromatin (often gene-poor) create different microenvironments that can be distinguished by measuring the fluorescence decay kinetics of Hoechst or DAPI. This allows researchers to probe chromatin compaction states in situ, providing functional insights alongside morphological data in nuclear studies [12].

Experimental Protocols

Staining of Fixed Cells for Nuclear Fragmentation Analysis

This protocol is optimized for visualizing nuclear morphology and detecting apoptotic bodies in fixed cells.

Reagents:

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Fixative (e.g., 4% Formaldehyde in PBS)

- Triton X-100 (0.1-0.5% in PBS for permeabilization)

- DAPI or Hoechst stain stock solution (e.g., 1-5 mg/mL in water) [6] [8]

- Mounting medium (optional, with or without antifade agent)

Procedure:

- Fixation: After removing culture medium, wash cells gently with PBS. Add enough fixative to cover the cells and incubate for 15-20 minutes at room temperature [6].

- Permeabilization: Remove fixative and wash cells twice with PBS. Apply permeabilization solution (0.1-0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 10-15 minutes.

- Staining: Prepare a working solution of DAPI (1 µg/mL) or Hoechst (1 µg/mL) in PBS [6]. Remove the permeabilization solution, add the staining solution to cover the cells, and incubate for at least 5 minutes at room temperature, protected from light.

- Washing and Mounting (Optional): For the highest signal-to-noise ratio, rinse the cells briefly with PBS. If required, add a drop of antifade mounting medium and apply a coverslip.

- Imaging: Image using a fluorescence microscope with standard DAPI filter sets (excitation ~360 nm, emission ~460 nm). For DAPI, excitation at 358 nm and detection at 461 nm is optimal [9].

Live-Cell Staining for Dynamic Studies

Monitoring nuclear changes in real-time requires dyes with low toxicity and high membrane permeability.

Reagents:

- Complete culture medium

- Hoechst 33342 stock solution (10 mg/mL in water) [6]

Procedure:

- Dye Preparation: Hoechst 33342 is strongly recommended over DAPI for live-cell staining due to its superior cell permeability and lower toxicity [6] [8]. Prepare an intermediate 10X solution by diluting the stock in culture medium to a final concentration of 10 µg/mL.

- Staining by Direct Addition: Without removing the culture medium, add 1/10 volume of the 10X dye solution directly to the well. Immediately mix thoroughly by gently pipetting the medium up and down or by swirling the plate [6].

- Incubation: Incubate cells at 37°C for 5-15 minutes, protected from light.

- Imaging: Image live cells directly. Note that washing is not necessary, as the unbound dye is virtually non-fluorescent [6]. For long-term live-cell tracking, consider using low-toxicity alternatives like CellLight Nucleus reagents, as prolonged exposure to Hoechst can affect cell function [8].

Diagram 1: Live-cell staining workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Catalog Numbers |

|---|---|---|

| DAPI (Dilactate or Dihydrochloride) | Cell-impermeant blue fluorescent DNA stain; preferred for fixed cells. Dilactate offers higher water solubility [8]. | Thermo Fisher D1306, D3571, D21490 (FluoroPure) [8] |

| Hoechst 33342 | Cell-permeant blue fluorescent DNA stain; recommended for live-cell staining due to its lipophilic ethyl group [6] [8]. | Thermo Fisher H1399, H21492 (FluoroPure) [8] |

| Hoechst 33258 | Cell-permeant blue fluorescent DNA stain; slightly more water-soluble and less permeant than Hoechst 33342 [6]. | Thermo Fisher H1398, H21491 (FluoroPure) [8] |

| FluoroPure Grade Dyes | High-purity (>98%) dyes for demanding applications like super-resolution and live-cell imaging, minimizing background noise [8]. | Thermo Fisher D21490 (DAPI), H21491 (Hoechst 33258) [8] |

| Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI | One-step mounting and staining solution for fixed cells, offering convenience and long-term fluorescence preservation [6]. | Biotium EverBrite Mounting Medium with DAPI [6] |

| Oxygen Scavenging System | Imaging buffer component (e.g., Glucose Oxidase/Catalase) critical for inducing blinking for SMLM super-resolution imaging [11]. | - |

Critical Considerations and Troubleshooting

- Cell Health and Toxicity: While Hoechst 33342 is suitable for live cells, some cell types may exhibit induced apoptosis or toxicity [6]. DAPI is considered a known mutagen [7]. Always use appropriate personal protective equipment and optimize dye concentration and exposure time to minimize cellular stress.

- Photoconversion and Photobleaching: Be aware that both DAPI and Hoechst can undergo photoconversion upon UV exposure, which may cause their fluorescence to appear in other channels (e.g., green) [6]. Using hardset mounting medium and controlling UV exposure can mitigate this issue.

- Staining of Non-Mammalian Cells: Bacteria and yeast stain more dimly than mammalian cells. Use higher dye concentrations (12-15 µg/mL) and longer incubation times (30 minutes) [6]. In yeast, these dyes can also preferentially stain dead cells.

- Solution Stability: Concentrated stock solutions of Hoechst (e.g., 10 mg/mL) in water are stable for years at 4°C when protected from light. However, dilute solutions of Hoechst are not stable for long-term storage, as the dye will precipitate or adsorb to the container [6]. DAPI is more stable in dilute solutions.

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting weak nuclear staining.

Within the framework of fluorescence microscopy protocols for nuclear fragmentation research, the selection of an appropriate fluorophore is a critical determinant for the success of an experiment. The assessment of nuclear integrity—encompassing morphology, DNA content, and membrane permeability—is fundamental to diverse fields, from cancer biology and toxicology to the study of apoptotic mechanisms. Among the most established tools for these analyses are the nucleic acid stains DAPI, Hoechst, and Propidium Iodide (PI). Each possesses distinct photophysical properties, cellular permeability characteristics, and applications. These dyes enable researchers to visualize nuclear architecture, perform cell cycle analysis, quantify apoptosis-specific changes like pyknosis and karyorrhexis, and differentiate viable from non-viable cells [13] [2] [14]. This Application Note provides a detailed comparison of these three fluorophores and outlines standardized protocols for their use in nuclear integrity assessment, providing a reliable resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

Fluorophore Characteristics and Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Properties and Binding Mechanisms

- DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole): This blue-fluorescent dye binds preferentially to the minor groove of double-stranded DNA, exhibiting a strong affinity for A-T-rich clusters. Its fluorescence is significantly enhanced upon DNA binding [15]. While it can permeate live cells, it does so inefficiently; its use is therefore most common and effective in fixed and permeabilized cells, or as a dead cell stain in viability assays due to its semi-permeable nature [16] [15].

- Hoechst Stains (33258, 33342): Like DAPI, these blue-fluorescent bisbenzimide dyes bind to A-T regions in DNA. A key distinction is that Hoechst 33342 is more lipophilic and effectively permeates the membranes of live cells, making it the preferred choice for live-cell nuclear staining. Hoechst 33258 is also cell-permeant but may require optimized conditions for certain cell types [13] [2] [17].

- Propidium Iodide (PI): This red-fluorescent dye binds to DNA and RNA by intercalating between base pairs, with no sequence preference. It is membrane-impermeant and generally excluded from viable cells with intact plasma membranes. Consequently, PI is a classic marker for dead cells in viability assays and for analyzing DNA content in fixed cells or cells with compromised membranes [13] [16].

Quantitative Spectroscopic and Application Data

The following table consolidates key characteristics and optimized application parameters for the three fluorophores, drawing from recent research to facilitate direct comparison and experimental planning.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Nuclear Staining Fluorophores

| Parameter | DAPI | Hoechst 33258 / 33342 | Propidium Iodide (PI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Binding Mode | Minor groove binding, A-T preference [15] | Minor groove binding, A-T preference [2] | Intercalation between base pairs [13] |

| Excitation/Emission Maxima | ~358 nm / ~461 nm [15] | ~352 nm / ~461 nm [2] | ~535 nm / ~617 nm [16] |

| Cell Permeability | Semi-permeable (better in fixed cells) [16] | Permeant (Hoechst 33342 > 33258) [2] [17] | Impermeant (excluded by live cells) [13] [16] |

| Primary Applications | Nuclear counterstaining, viability assessment (fixed/dead cells) [16] [14] | Live-cell nuclear staining, nuclear morphology assays [2] [18] | Cell viability (dead cell marker), cell cycle analysis (fixed cells) [13] [16] |

| Typical Working Concentration (Microscopy) | 1.0 µg/mL [14] | 2.0 µg/mL [2] | 50 µg/mL [13] |

| Incubation Time | 5-15 min [14] | 5-30 min (live cells) [2] | 5-15 min [13] |

| Compatibility with Fixation | Excellent [15] | Excellent [17] | Required for cell cycle analysis on non-viable cells [13] |

| Key Distinguishing Feature | Sharp nuclear contrast, semi-permeable nature | Low toxicity for long-term live-cell imaging [17] | Membrane impermeability ideal for viability staining |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Combined Nuclear Morphology and Viability Assessment

This protocol is adapted from recent studies on apoptosis detection and sperm membrane integrity, allowing for simultaneous evaluation of nuclear morphology changes (e.g., condensation, fragmentation) and cell viability in adherent cell cultures [16] [14].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- DAPI Stock Solution: 1 mg/mL in deionized water. Store at 4°C [14].

- Propidium Iodide (PI) Stock Solution: 1 mg/mL in deionized water. Store in the dark at 4°C [13].

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Cell Permeabilization Solution: 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS [14].

- Fixative Solution: 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS.

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding and Treatment: Seed cells (e.g., LNCaP, MDA-MB-231) onto a multi-well chambered cover slip and allow them to adhere. Apply the experimental treatment (e.g., apoptosis inducer like cycloheximide) for the desired duration [14].

- Staining Solution Preparation: Prepare a dual-stain solution in PBS containing 1.0 µg/mL DAPI and 50 µg/mL PI [13] [14].

- Incubation and Imaging:

- Aspirate the culture medium from the wells and gently wash the cells with pre-warmed PBS.

- Add the DAPI/PI staining solution to cover the cells.

- Incubate for 15 minutes at 37°C, protected from light.

- Aspirate the staining solution and wash twice with PBS.

- Add a small volume of PBS or live-cell imaging medium to prevent drying.

- Immediately image using a fluorescence microscope with DAPI and TRITC/Cy3 filter sets.

Data Interpretation:

- DAPI Channel: Visualizes all nuclei. Apoptotic cells will show reduced nuclear area, perimeter, and increased fluorescence intensity due to chromatin condensation (pyknosis), or nuclear fragmentation (karyorrhexis) [14].

- PI Channel: Identifies dead cells with compromised plasma membranes. Co-localization of bright DAPI and PI signals indicates a dead cell, potentially in a late apoptotic or necrotic state.

Protocol 2: Quantitative Spectrofluorometric Analysis of Nuclear Condensation

This protocol, based on the work of Anticancer Research (2017) and Scientific Reports (2021), details a method for quantifying apoptosis-induced nuclear condensation in a 96-well plate format using Hoechst 33258, suitable for high-throughput screening [2] [14].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Hoechst 33258 Stock Solution: 1 mg/mL in deionized water. Store at 4°C [2].

- Apoptosis Inducer: e.g., Cisplatin, Staurosporine, or Cycloheximide.

- Cell Culture Medium appropriate for the cell line.

Procedure:

- Cell Treatment: Seed cells (e.g., HepG2, HK-2) in a 96-well plate. After adherence, treat with apoptotic inducers for 6-48 hours [2].

- Sample Preparation:

- Centrifuge the plate (5 min, 8000×g, RT) to sediment all cells to the bottom of the wells.

- Carefully remove 70 µL of the supernatant from each well.

- Replace with 70 µL of 1X PBS.

- Hoechst Staining and Measurement:

- Add Hoechst 33258 dye to each well to achieve a final concentration of 2 µg/mL [2].

- Incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature, protected from light.

- Measure fluorescence using a plate reader with excitation at ~352 nm and emission at ~461 nm.

Data Interpretation: An increase in Hoechst 33258 fluorescence intensity in treated samples relative to untreated controls is indicative of nuclear condensation and fragmentation, hallmarks of apoptosis. This method provides quantitative, high-throughput data that correlates with other apoptosis assays like TUNEL [2].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the logical workflow for the dual-staining protocol and the molecular mechanism of dye action in assessing nuclear integrity.

The strategic selection of DAPI, Hoechst, or Propidium Iodide is paramount for accurate nuclear integrity assessment. Hoechst 33342 is unequivocally the superior choice for live-cell experiments requiring visualization of nuclear dynamics over time due to its effective permeability and low toxicity [17]. In contrast, DAPI provides exceptional nuclear contrast in fixed-cell preparations and can be leveraged in viability assays to identify dead cells, given its semi-permeable nature [16] [14]. Propidium Iodide remains the gold standard for identifying dead cells with compromised membranes and is indispensable for precise cell cycle analysis via flow cytometry in fixed-cell systems [13] [16].

Researchers can combine these dyes for multiparametric analysis. For instance, Hoechst 33342 and PI can be used together to distinguish live and dead populations in a mixed culture, while DAPI staining of fixed samples can be quantitatively analyzed to detect subtle, apoptosis-driven morphological changes like nuclear shrinkage (pyknosis) [14]. Furthermore, the development of quantitative spectrofluorometric assays using Hoechst 33258 enables high-throughput, sensitive detection of nuclear condensation, offering a robust alternative to more complex methods like the TUNEL assay [2].

In conclusion, a deep understanding of the distinct properties of these common nuclear stains allows for informed experimental design. The protocols and data presented herein provide a solid foundation for researchers in drug development and basic science to reliably assess nuclear integrity, a critical parameter in cell health and death studies.

Fundamentals of Wide-Field Epifluorescence Microscopy for Nuclear Imaging

Wide-field epifluorescence microscopy is a fundamental imaging technique where the entire specimen is illuminated simultaneously with a light source, and the resulting fluorescence is collected through the objective lens to form an image [19] [20]. This technique stands in contrast to confocal microscopy, which uses point-scanning with lasers and pinholes to reject out-of-focus light [21]. In epifluorescence microscopy, both the excitation light and the collection of emitted fluorescence occur through the same objective, with a dichroic mirror acting as a wavelength-specific filter to separate the excitation and emission light paths [22] [23].

This methodology is particularly valuable for nuclear imaging in the context of cell biology and drug development, enabling researchers to visualize nuclear architecture, monitor processes like nuclear transport, and investigate nuclear fragmentation events [24] [25]. The technique offers several practical advantages, including relatively straightforward operation, rapid image acquisition capable of capturing dynamic cellular processes, and lower equipment costs compared to confocal systems [21] [26]. These characteristics make wide-field epifluorescence microscopy an accessible and powerful tool for initial screening and live-cell imaging applications in nuclear research.

Technical Fundamentals and Light Path

The core principle of wide-field epifluorescence microscopy involves a specific sequence of optical events that ultimately generate a fluorescent image. The process begins when high-intensity light from a mercury-arc lamp, xenon-arc lamp, or modern LED source passes through an excitation filter, which selects the specific wavelength required to excite the target fluorophore [19] [22]. This filtered light is then reflected by a dichroic mirror downward through the objective lens, which focuses it onto the entire specimen [23].

Fluorophores within the specimen absorb this high-energy excitation light, causing electrons to jump to a higher energy state. As these electrons return to their ground state, they release energy as photons of lower energy and longer wavelength (Stokes shift) [22]. This emitted fluorescence light is collected by the same objective lens and passes back up through the microscope. Since the emitted light is of a longer wavelength, it can pass through the dichroic mirror and subsequently through an emission filter (or barrier filter) that further removes any stray excitation light, ensuring that only the fluorescence signal reaches the detector (camera or eyepiece) [22] [20].

The following diagram illustrates this fundamental light path and the principle of fluorescence:

Microscope Components and Configuration

Core System Components

A wide-field epifluorescence microscope is comprised of several key components that work in concert to generate high-quality fluorescent images, each playing a critical role in the optical pathway [19] [22] [23]:

- Light Source: Provides high-intensity illumination for fluorophore excitation. Traditional sources include mercury-arc and xenon-arc lamps, though LED sources are now widely adopted for their longevity and stability [19] [22].

- Excitation Filter: Selects the specific wavelength range needed to excite the target fluorophore from the broad spectrum emitted by the light source [22].

- Dichroic Mirror: A wavelength-specific beam splitter that reflects the short-wavelength excitation light toward the specimen while transmitting the longer-wavelength emission light toward the detector [22] [23].

- Objective Lens: Serves both as a condenser for focusing excitation light onto the specimen and for collecting the emitted fluorescence. High numerical aperture (NA) objectives are crucial for maximizing light collection [22].

- Emission Filter (Barrier Filter): Further purifies the emitted light by blocking any residual excitation light that may have passed through the dichroic mirror, ensuring only the fluorescence signal reaches the detector [22].

- Detector: Typically a digital camera such as a CCD, CMOS, or sCMOS sensor that captures the fluorescence image for visualization and analysis [19].

Quantitative Comparison of Microscope Components

Table 1: Comparison of key components in wide-field epifluorescence microscopy

| Component | Options | Key Characteristics | Performance Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light Source | Mercury-arc lamp | High intensity, peaks in UV (~365 nm) and green/yellow (546/579 nm) | Limited lifetime (200-300 hrs), intense but uneven spectrum [19] |

| Xenon-arc lamp | More uniform spectrum, extends into infrared | Longer lifetime (400-600 hrs), lower peak intensity than mercury [19] | |

| LED | Narrow wavelength bands, full spectrum (365-770 nm) | Long lifetime (~50,000 hrs), stable output, minimal heat [19] [22] | |

| Detector | CCD | High quantum efficiency, good for low light | Slower readout, used for gradual signal accumulation [26] |

| EMCCD | Electron multiplication for low-light detection | Fast detection of low-light fluorescence, reduced noise [26] | |

| sCMOS | Low noise, high speed, high resolution | Balanced performance for speed and sensitivity [19] | |

| Objective Lens | Standard | Varying NA and magnification | Brightness proportional to NA⁴/magnification² [22] |

| High NA (≥1.4) | Optimized for fluorescence | Maximizes light collection, improves resolution [22] [26] | |

| Oil Immersion | Reduces refractive index mismatch | Increases effective NA and brightness [22] |

Microscope Configurations

Wide-field epifluorescence microscopes are available in two primary configurations, selected based on sample type and experimental needs [22] [20]:

- Upright Microscopes: Illuminate the specimen from below the stage, with the objective lens located above the sample. This configuration is ideally suited for examining fixed tissues or cells mounted on microscope slides [22] [20].

- Inverted Microscopes: Feature illumination from above the stage and objectives situated beneath the sample. This design is particularly advantageous for observing live cells in culture dishes or suspension, allowing easy access for microinjection or manipulation while maintaining sterile conditions [22] [20].

Applications in Nuclear Imaging

Wide-field epifluorescence microscopy serves as an indispensable tool for investigating nuclear structure and function, with particular relevance to studies of nuclear fragmentation and associated cellular processes.

Visualizing Nuclear Architecture and Chromatin Organization

The technique enables detailed visualization of global nuclear organization through the use of DNA-binding dyes such as DAPI and Hoechst [25]. The distinct staining patterns generated by these fluorophores allow researchers to differentiate between condensed heterochromatin and more open euchromatin regions within the nucleus [25]. This capability is fundamental for identifying dramatic nuclear changes such as condensation and fragmentation during processes like apoptosis. Furthermore, when combined with immunofluorescence techniques using antibodies specific to nuclear proteins (lamins, emerin, histones with specific modifications), wide-field microscopy can reveal changes in nuclear envelope integrity and epigenetic states in response to cellular stress or drug treatments [25].

Investigating Nuclear Transport Mechanisms

Wide-field epifluorescence, particularly in its narrower-field implementation, has been successfully employed to track the dynamics of single molecules interacting with nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) [24]. This application can achieve remarkable temporal resolution (2 ms) and spatial precision (~15 nm for stationary particles), enabling researchers to directly measure the kinetics of cargo molecules as they traverse the nuclear envelope [24]. Such detailed analysis of transport dynamics provides insights into how the nucleocytoplasmic barrier function might be compromised in diseased states or in response to therapeutic interventions.

Monitoring Mechanoregulation and Nuclear Fragmentation

Cells constantly sense and respond to their mechanical environment, and the nucleus serves as a central organelle in this mechanoregulation process [25]. Wide-field microscopy allows researchers to correlate changes in nuclear morphology, such as the blebbing and rupturing characteristic of fragmentation, with alterations in the cellular mechanical environment [25]. By visualizing the localization of mechanosensitive transcription factors (YAP/TAZ, MRTF-A, β-catenin) in response to mechanical stimuli, researchers can gain insights into the molecular pathways that connect physical forces to nuclear integrity and gene expression changes relevant to disease progression and drug responses [25].

Experimental Protocol for Nuclear Fragmentation Analysis

Sample Preparation and Staining

Table 2: Essential reagents for nuclear imaging studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Nuclear Imaging |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Stains | DAPI, Hoechst | DNA intercalating dyes that label total chromatin, revealing nuclear morphology and condensation state [25] |

| Antibodies for Nuclear Proteins | Anti-lamin A/C, anti-emerin, anti-histone modifications | Identify specific nuclear envelope and chromatin components to assess structural integrity [25] |

| Viability Indicators | Propidium iodide, Annexin V conjugates | Distinguish viable, apoptotic, and necrotic cells based on membrane integrity and phospholipid exposure |

| Secondary Antibodies | Alexa Fluor conjugates, FITC-labeled secondaries | Amplify signal from primary antibodies for multiplexed imaging of multiple nuclear targets [21] |

| Mounting Media | Antifade mounting media | Preserve fluorescence and reduce photobleaching during imaging and storage |

Cell Culture and Treatment: Plate appropriate cells (e.g., primary cells or cell lines relevant to your research) on sterile glass-bottom dishes or coverslips. Grow to 60-80% confluence before applying experimental treatments (e.g., chemotherapeutic agents, oxidative stress) known to induce nuclear fragmentation.

Fixation: Aspirate culture medium and rinse cells gently with pre-warmed phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature. Note: Methanol fixation can be used as an alternative for certain antigens but may alter nuclear morphology.

Permeabilization and Blocking: Permeabilize cells with 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes. Wash with PBS, then incubate with blocking buffer (e.g., 1-5% BSA in PBS) for 30-60 minutes to reduce non-specific antibody binding.

Staining:

- For nuclear staining: Incubate with DAPI (1 µg/mL) or Hoechst (5 µg/mL) for 10 minutes [25].

- For immunofluorescence: Incubate with primary antibodies (e.g., anti-lamin B1, anti-γH2AX) diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Wash thoroughly, then incubate with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature protected from light.

- For multiplexing: Ensure minimal spectral overlap between fluorophores when designing panels.

Mounting: For coverslips, mount onto glass slides using antifade mounting medium. Seal edges with clear nail polish to prevent drying and movement during imaging.

Image Acquisition Workflow

The following diagram outlines the key steps in image acquisition and analysis for nuclear fragmentation studies:

Microscope Setup:

- Turn on the light source (allow mercury lamps 15-30 minutes for stabilization if used).

- Select a high numerical aperture (NA) objective (60x or 100x oil immersion) to maximize resolution and light collection [22].

- Ensure the correct filter sets are installed for your fluorophores.

Camera Configuration:

- Set appropriate exposure times to avoid saturation while maximizing dynamic range.

- For low-signal samples, consider binning or increasing gain, but be aware of potential noise introduction.

- For time-lapse imaging of live cells, minimize exposure to reduce phototoxicity.

Image Acquisition:

- Focus carefully on the nuclear plane using brightfield illumination if possible before switching to fluorescence.

- Acquire images systematically across treatment conditions, maintaining consistent settings.

- For z-stack acquisition, set appropriate step sizes (0.2-0.5 µm) to capture the entire nuclear volume.

Image Export and Analysis:

- Save images in non-proprietary formats (TIFF) for analysis.

- Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, CellProfiler) for quantitative assessment of nuclear morphology, fragmentation indices, and fluorescence intensity measurements.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative Parameters for Nuclear Fragmentation

Table 3: Key quantitative metrics for nuclear fragmentation analysis

| Parameter | Measurement Method | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Area | Pixel count of nuclear region defined by DAPI staining | Changes in nuclear size may indicate stress responses or pathological states |

| Nuclear Circularity | 4π(Area/Perimeter²) | Deviation from circularity may indicate early morphological abnormalities |

| Fragmentation Index | Count of discrete DAPI-positive bodies per cell | Direct measure of nuclear integrity; increased count indicates fragmentation |

| Intensity Distribution | Coefficient of variation of pixel intensities within nucleus | Heterogeneous staining may suggest chromatin condensation |

| Foci Counting | Automated detection of bright foci (e.g., γH2AX) within nucleus | Quantification of DNA damage response elements |

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- High Background Fluorescence: Increase stringency of washes during staining, optimize antibody concentrations, or include additional blocking steps [21].

- Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio: Increase exposure time, use higher NA objectives, or consider using brighter fluorophores or signal amplification methods [22].

- Photobleaching: Reduce illumination intensity, use antifade mounting media, or limit exposure time during image acquisition [22].

- Channel Crosstalk: Optimize filter sets, use sequential imaging of fluorophores with overlapping spectra, and include single-stain controls for compensation [21].

Advantages and Limitations

Strengths of Wide-Field Epifluorescence Microscopy

Wide-field epifluorescence microscopy offers several compelling advantages for nuclear imaging applications [21] [26] [23]:

- High Speed Imaging: The simultaneous illumination of the entire field of view enables rapid capture of dynamic processes, making it ideal for live-cell imaging and high-throughput applications.

- Simplicity of Operation: Compared to confocal systems, wide-field microscopes are generally less complex to operate and maintain, with lower initial investment costs.

- Direct Observation: Samples can be observed directly through eyepieces, facilitating quick sample assessment and selection of regions of interest.

- Low Phototoxicity: When properly configured, wide-field systems can use lower light intensities than point-scanning confocals, reducing photodamage to live specimens.

- Compatibility: Easily combined with other contrast-enhancement techniques like phase contrast or DIC for correlative imaging of morphology and fluorescent labels.

Limitations and Considerations

Despite its utility, wide-field epifluorescence microscopy presents certain limitations that researchers must consider [21] [26] [20]:

- Out-of-Focus Light: The most significant limitation is the collection of fluorescence from outside the focal plane, which can reduce image contrast and complicate interpretation, particularly in thick samples.

- Limited Optical Sectioning: Without computational approaches like deconvolution, wide-field systems cannot naturally resolve structures along the z-axis as effectively as confocal microscopes.

- Reduced Resolution in Thick Specimens: Scattered light from thick samples can further degrade image quality and resolution.

- Background Fluorescence: The entire specimen is illuminated, potentially increasing autofluorescence contributions from non-target regions.

For applications requiring superior z-resolution in thick samples or precise optical sectioning, confocal microscopy remains the preferred approach [21]. However, for many nuclear imaging applications, particularly those involving monolayer cells or requiring high temporal resolution, wide-field epifluorescence microscopy provides an optimal balance of performance, ease of use, and cost-effectiveness.

In fluorescence microscopy research, particularly in the study of nuclear fragmentation during apoptosis, the preparation of the sample is a critical determinant of experimental success. Fixation is the process of preserving cellular structure and immobilizing antigens to maintain a "lifelike" appearance of cells by preventing autolysis and degradation caused by proteolytic enzymes [27]. The overarching goal of fixation is to stabilize cell morphology and tissue architecture while ensuring that antigenic sites remain accessible to detection reagents like antibodies or fluorescent dyes [28]. For nuclear fragmentation research, this is especially crucial as it allows researchers to accurately visualize and quantify subtle nuclear changes such as chromatin condensation (pyknosis), nuclear shrinkage, and the formation of apoptotic bodies [2] [14].

The process of fixation plays four essential roles: it preserves and stabilizes cell morphology and tissue architecture; it inactivates proteolytic enzymes that could otherwise degrade the sample; it strengthens samples to withstand further processing and staining; and it protects samples against microbial contamination and possible decomposition [28]. When studying nuclear alterations, improper fixation can lead to artifacts that either mask genuine apoptotic phenomena or create false morphological appearances, thereby compromising experimental validity. Thus, a well-optimized fixation protocol serves as the foundation for reliable detection and quantification of nuclear fragmentation events, which are hallmarks of programmed cell death.

Categories of Fixatives and Their Mechanisms

Fixatives are broadly categorized into two main classes based on their mechanism of action: cross-linking fixatives and precipitating fixatives. Each category has distinct advantages and limitations that must be considered in the context of nuclear fragmentation research.

Cross-Linking Fixatives

Cross-linking fixatives, primarily aldehyde-based, form covalent chemical bonds (cross-links) between proteins in the cell and their surroundings [29]. The most commonly used cross-linking fixative is formaldehyde, typically prepared as paraformaldehyde (PFA) for laboratory use [28] [29]. Formaldehyde shows broad specificity for most cellular targets, reacting with primary amines on proteins and nucleic acids to form partially reversible methylene bridge cross-links [28]. The standard concentration for cell fixation is 3-4% paraformaldehyde, typically applied for 5-10 minutes for isolated cells or up to 30 minutes for larger tissue samples [29].

Glutaraldehyde is a stronger cross-linker that reacts with amino and sulfhydryl groups and possibly with aromatic ring structures [28]. While it provides excellent structural preservation, it penetrates tissue more slowly than formaldehyde and can cause greater antigen masking due to its extensive cross-linking capacity. For this reason, glutaraldehyde is more frequently used in electron microscopy than in routine fluorescence microscopy studies of nuclear morphology.

Precipitating Fixatives

Precipitating fixatives (organic solvents) include methanol, ethanol, and acetone. These solvents work by precipitating and coagulating large protein molecules, thereby denaturing them [28] [29]. They remove lipids, dehydrate tissue, and denature and precipitate proteins in samples [29]. Acetone is particularly effective for cold fixation (at -20°C) and is suitable for preserving temperature-sensitive antigens [27].

These fixatives penetrate cells and tissues quickly, and the fixation process is rapid [27]. They generally do not significantly mask antigen epitopes, meaning antigen retrieval is often unnecessary [27]. Additionally, they can fix both lipids and nucleic acids, making them suitable for detecting nuclear proteins and small molecules [27]. A significant drawback, however, is that they dehydrate cells, which can cause some morphological disruption and adversely affect cell membrane integrity [27].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Fixatives for Fluorescence Microscopy

| Fixative Type | Examples | Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-linking | 3-4% Paraformaldehyde [29] | Forms covalent bonds between proteins [29] | Excellent structural preservation [29] | Can mask antigens; may require retrieval [29] |

| Cross-linking | Glutaraldehyde [28] | Strong protein crosslinker [28] | Superior ultrastructure preservation [28] | Slow penetration; often requires quenching [28] |

| Precipitating | Methanol [29] [30] | Protein precipitation and dehydration [29] | Fast; minimal antigen masking [27] | Disrupts membrane integrity [27] |

| Precipitating | Acetone [29] [27] | Protein precipitation at low temperatures [27] | Good for temperature-sensitive antigens [27] | Harsh on cellular structures [27] |

Fixation Protocols for Different Sample Types

The optimal fixation protocol varies significantly depending on whether one is working with adherent cell lines, cells in suspension, or tissue samples. Below are detailed methodologies optimized for nuclear morphology studies in apoptosis research.

Protocol for Adherent Cell Lines

Adherent cells are particularly amenable to nuclear fragmentation studies as they remain in their growth environment throughout initial fixation steps, minimizing artificial morphological changes.

- Wash cells in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2, to remove culture medium and debris [30].

- Fix cells in 3.7% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.2) for 15 minutes at room temperature [30].

- Wash once with PBS for 5 minutes at room temperature to remove excess fixative [30].

- Permeabilize by covering cells with methanol for 5 minutes at room temperature [30]. Alternative permeabilization methods include:

- Wash cells in PBS, pH 7.2 [30].

- Proceed with staining using an appropriate DNA-specific fluorochrome such as DAPI or Hoechst 33258 [30].

Protocol for Cells in Suspension

Cells growing in suspension require additional steps to ensure proper attachment to slides without loss of morphological integrity.

- Wash cells in PBS, pH 7.2 [30].

- Centrifuge (5 minutes at 500× g) to pellet cells [30].

- Prepare cytospin slides by resuspending cell pellet and centrifuging onto poly-L-lysine coated slides [30].

- Air dry cells briefly to ensure adhesion [30].

- Follow steps 2-6 from the adherent cell protocol above [30].

Specialized Protocol for Confocal Microscopy

For high-resolution imaging of nuclear morphology changes using confocal laser scanning microscopy, enhanced fixation protocols are recommended to preserve three-dimensional architecture.

- Grow cells on poly-L-lysine coated coverslips to ensure firm attachment [30].

- Wash once with PBS for 5 minutes at room temperature [30].

- Fix in 3.7% PFA in cytoskeletal (CSK) buffer for 10 minutes at room temperature [30].

- Wash three times in CSK buffer without sucrose for 5 minutes each [30].

- Permeabilize with 0.2% Triton X-100 in CSK buffer without sucrose for 5 minutes [30].

- Wash once in PBS [30].

- Proceed with staining and mount using anti-fade mounting medium [30].

Diagram 1: Cell Fixation and Staining Workflow. This diagram outlines the key decision points and steps in preparing cells for nuclear fluorescence imaging.

Optimizing Stain Penetration and Antigen Accessibility

Achieving optimal fluorochrome penetration while maintaining structural integrity requires careful balancing of fixation and permeabilization conditions. Permeabilization is particularly crucial for nuclear stains like DAPI and Hoechst 33258, which must access DNA within the nucleus.

Permeabilization Methods

Effective permeabilization creates sufficient pores in cellular membranes to allow fluorescent dyes to reach their intracellular targets without causing excessive morphological damage.

Detergent-based permeabilization: Triton X-100 (0.1-0.5%) or saponin are commonly used to solubilize membrane lipids while preserving protein structure [30]. For nuclear staining, 0.2% Triton X-100 applied for 5 minutes at room temperature is generally effective [30].

Solvent-based permeabilization: Methanol and acetone both act as both fixatives and permeabilizing agents due to their ability to dissolve lipids [27]. Methanol treatment (5 minutes at room temperature) following aldehyde fixation is particularly effective for nuclear staining protocols [30].

Antigen Retrieval Techniques

For cross-linking fixatives that may mask antigen epitopes or hinder dye access, various antigen retrieval methods can be employed to restore accessibility:

Heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER): Treatment with 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95°C for 20 minutes is highly effective for reversing formaldehyde-induced cross-links [28].

Enzymatic retrieval: Proteolytic enzymes such as proteinase K (20 μg/mL for 10-20 minutes at 37°C) can digest proteins that obscure access to nuclear targets [29].

Alternative retrieval methods: Combining Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) with heat treatment (95-100°C for 10-40 minutes) provides another effective approach for restoring antigen accessibility [29].

Table 2: Optimization Scheme for Fixation and Stain Penetration

| Sample | Fixation Method | Permeabilization/Retrieval | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard nuclear staining | 3.7% PFA, 15 min [30] | 0.2% Triton X-100, 5 min [30] | Routine apoptosis detection [14] |

| Membrane protein preservation | Methanol, 5 min [30] | Already permeabilized [30] | Combined membrane/nuclear staining |

| Labile nuclear antigens | Acetone, -20°C, 5-10 min [29] | Already permeabilized [29] | Temperature-sensitive targets [27] |

| Strongly cross-linked samples | 3-4% PFA, 15-30 min [29] | Proteinase K, 37°C, 10-20 min [29] | After over-fixation [29] |

| Enhanced penetration | 3.7% PFA, 15 min [30] | Methanol + Acetone sequence [30] | Challenging-to-stain nuclei |

Quantitative Assessment of Nuclear Morphology

Well-fixed and properly stained samples enable precise quantification of nuclear morphology changes characteristic of apoptosis. Fluorescence microscopy combined with image analysis software allows researchers to extract multiple parameters indicative of nuclear fragmentation.

Key Nuclear Parameters in Apoptosis

During apoptosis, nuclei undergo characteristic changes that can be quantified using fluorescence microscopy:

Nuclear area: Significant reduction in nuclear size (pyknosis) is a hallmark of early apoptosis. Studies show apoptotic cells can exhibit up to 50% reduction in nuclear area compared to healthy cells [14].

Nuclear perimeter: Irregular nuclear contours and invaginations lead to increases in perimeter length during intermediate stages of apoptosis [14].

Major and minor axis: The aspect ratio of nuclei changes as spherical nuclei become elongated or irregularly shaped during fragmentation [14].

Staining intensity: Chromatin condensation leads to increased local fluorochrome concentration, resulting in enhanced fluorescence intensity. Research demonstrates a 1.5 to 2-fold increase in DAPI fluorescence intensity in apoptotic cells [14].

Nuclear fragmentation: Advanced apoptosis leads to nuclear disintegration into multiple discrete fragments that can be quantified as discrete objects [2] [14].

Spectrofluorometric Assay for Nuclear Changes

Beyond morphological analysis, a quantitative spectrofluorometric assay using Hoechst 33258 can detect nuclear condensation and fragmentation in intact cells. This approach offers several advantages for apoptosis research:

Sensitivity: The assay detects nuclear changes induced by various apoptotic inducers (cisplatin, staurosporine, camptothecin) with sensitivity comparable to TUNEL assay [2].

Throughput: The method is suitable for 96-well plates, enabling rapid screening of multiple conditions [2].

Quantification: Fluorescence intensity increases proportionally with chromatin condensation, allowing precise quantification of apoptotic progression [2].

The optimal Hoechst 33258 concentration for this assay is 2 μg/mL with 5 minutes incubation time, providing an optimal signal-to-noise ratio for detecting nuclear changes [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Nuclear Staining

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Nuclear Fluorescence Studies

| Reagent | Composition/Preparation | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (3-4%) | 3.7 g PFA in 100 mL PBS + 2 drops 10N NaOH [30] | Cross-linking fixative | Preserves structure; may require antigen retrieval [30] |

| Methanol Fixative | 100% methanol at -20°C [29] | Precipitating fixative and permeabilizer | Fast penetration; may disrupt membranes [27] |

| Permeabilization Buffer | 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS [30] | Membrane permeabilization | Creates pores for dye access; use after aldehyde fixation [30] |

| DAPI Stain | 1.0 μg/mL in PBS [14] | DNA-specific fluorochrome | Blue fluorescence (ex 358 nm, em 461 nm); nuclei counterstain [14] |

| Hoechst 33258 | 2 μg/mL in PBS [2] | DNA-binding probe for apoptosis detection | Fluorescence increases with chromatin condensation [2] |

| Propidium Iodide | 10 μg/mL in PBS [30] | DNA intercalating dye | Red fluorescence (ex 536 nm, em 617 nm); not cell-permeant [30] |

| Mounting Medium with Anti-fade | Polyvinyl alcohol + glycerol [30] | Preserves fluorescence | Reduces photobleaching; essential for quantitative work [30] |

Diagram 2: Nuclear Morphology Changes in Cell Death. This diagram illustrates the progression of nuclear changes during different modes of cell death, highlighting key morphological transitions.

Proper sample preparation through optimized fixation and staining protocols is fundamental to successful nuclear fragmentation research using fluorescence microscopy. The choice between cross-linking and precipitating fixatives represents a critical decision point that balances structural preservation with stain accessibility. The protocols presented here for different sample types, combined with appropriate permeabilization and antigen retrieval methods, provide researchers with a solid methodological foundation for investigating nuclear morphology changes in apoptosis. When properly executed, these techniques enable precise quantification of key parameters such as nuclear area, perimeter, and fragmentation index, facilitating robust and reproducible research in drug development and cell death mechanisms. As fluorescence microscopy technologies continue to advance, with new approaches like topological data analysis [31] and scattering-resistant imaging [32] emerging, the importance of standardized, optimized sample preparation becomes increasingly critical for generating reliable, quantitative data in nuclear fragmentation studies.

A Step-by-Step Protocol for Imaging and Quantifying Nuclear Fragmentation

Within the context of fluorescence microscopy research into nuclear fragmentation, a robust and reproducible sample preparation protocol is paramount. Nuclear fragmentation, a key hallmark of processes such as apoptosis and cellular stress, requires precise visualization and quantification [33] [34]. This application note details a comprehensive workflow for the preparation, fixation, staining, and mounting of adherent cell cultures, optimized specifically for high-resolution fluorescence imaging of nuclear structures. The protocols herein are designed to preserve delicate nuclear morphology, minimize background fluorescence, and ensure the reliable detection of subcellular features, thereby providing a solid foundation for quantitative analysis in drug development and basic research.

The complete experimental journey, from preparing the coverslip to acquiring an image, is outlined below. This workflow ensures optimal cell adhesion, preservation, and staining for high-quality microscopy.

Detailed Protocols and Methodologies

Coverslip Preparation and Cell Seeding

Proper coating is critical for cell adhesion, especially for sensitive stem cells or primary cultures.

3.1.1 Coating with a Defined Matrix (for ES cells, iPS cells, MSCs, or NSCs) [35]

- Procedure:

- Place a sterile coverslip into each well of a 24-well plate.

- Thaw the culture matrix at 2–8 °C.

- Dilute the matrix 1:100 in sterile 1X PBS. Mix gently without vortexing.

- Immediately add approximately 400 µL of the diluted matrix to each well, ensuring the coverslip is submerged.

- Incubate at 37 °C for 2–3 hours.

- Immediately before plating cells, aspirate the matrix solution and rinse once with sterile 1X PBS.

- Plate cells at the desired density in complete growth medium.

3.1.2 Coating with Poly-L-ornithine and Fibronectin (for Neural Stem Cells) [35]

- Reagent Preparation:

- Poly-L-ornithine (1X): Dilute a 15 mg/mL stock solution 1000-fold in sterile PBS to a final concentration of 15 µg/mL.

- Fibronectin Solution (1X): Dilute human or bovine fibronectin in sterile PBS to 1 µg/mL.

- Procedure:

- Place a sterile coverslip into each well of a 24-well plate.

- Add 0.5 mL of 1X Poly-L-ornithine solution to each well. Incubate overnight at 37 °C.

- Aspirate the solution and wash each well 3 times with 1 mL of sterile PBS.

- Add 0.5 mL of sterile PBS to each well and incubate overnight at 37 °C.

- Aspirate the PBS, wash once, then add 0.5 mL of 1 µg/mL Fibronectin solution.

- Incubate at 37 °C for 3–24 hours.

- Aspirate the Fibronectin solution, wash once with PBS, and plate cells at the desired density.

Cell Fixation

Fixation preserves cellular architecture at the moment of fixation. The choice of fixative is critical for antigen preservation and compatibility with downstream stains.

- Procedure (Cross-linking with Paraformaldehyde) [35] [36]:

- Once cells reach ~70% confluency, carefully aspirate the culture media.

- Wash cells twice gently with room temperature 1X PBS to remove residual media and serum.

- Add 300–400 µL of 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS to each well, ensuring the coverslip is fully covered.

- Incubate for 20 minutes at room temperature.

- Aspirate the PFA and gently rinse the fixed cells twice with 1X PBS. Fixed cells on coverslips can be stored in PBS at 4 °C for up to three months.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Fixation Methods

| Fixative | Mechanism | Best For | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) [35] [36] | Cross-linking proteins | Most applications, especially preserving soluble proteins and superior structural detail. | Excellent morphological preservation; compatible with many fluorescent proteins. | Can mask some epitopes, requiring antigen retrieval. |

| Methanol [36] | Precipitation and dehydration | Some nuclear antigens, cytoplasmic structures. | Permeabilizes cells; can reduce background. | Can destroy some protein epitopes and alter morphology. |

Permeabilization and Staining

Permeabilization allows dyes and antibodies to access intracellular targets. For nuclear fragmentation studies, dyes that intercalate with DNA are essential.

3.3.1 Permeabilization Protocol

- Procedure: After fixation and PBS rinses, incubate cells with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes at room temperature [33] [35]. Rinse three times with PBS before proceeding to staining.

3.3.2 Propidium Iodide Staining for Nuclear DNA

- Procedure (Adapted from flow cytometry protocol) [33] [34]: After permeabilization, incubate cells with a solution of Propidium Iodide (PI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Typically, this involves a 15-30 minute incubation at room temperature, protected from light. Rinse thoroughly with PBS or a wash buffer (e.g., 0.1% BSA in PBS) to remove unbound dye [35].

Table 2: Common Nuclear Stains for Fluorescence Microscopy

| Stain | Excitation/Emission | Target / Mechanism | Key Application in Nuclear Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propidium Iodide (PI) [33] [34] | ~535/~617 nm | Intercalates into double-stranded nucleic acids; impermeant to live cells. | Labels fragmented nuclear DNA, yielding a hypodiploid signal that marks cell death. |

| Hoechst 33258 [34] | ~345/~460 nm | Binds to the minor groove of AT-rich DNA sequences; cell-permeant. | General nuclear counterstain; used to confirm trends in cell death rates. |

| DAPI [37] | ~358/~461 nm | Binds strongly to AT-rich regions in DNA. | General nuclear counterstain and visualization of nuclear envelopes. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Cell Preparation and Staining

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Poly-L-ornithine [35] [36] | Coating to enhance adhesion of cells to glass coverslips. | Universal coating compatible with most adherent cell types. |

| Fibronectin [35] | Defined extracellular matrix protein for specific cell types. | Used for MSCs or NSCs under serum-free conditions. |

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) [35] [36] | Cross-linking fixative for optimal preservation of cellular morphology. | Typically used at 4% in PBS. |

| Triton X-100 [33] [35] | Non-ionic detergent for permeabilizing cell membranes post-fixation. | Allows intracellular access for dyes and antibodies. |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) [33] [34] | Fluorescent nuclear dye that labels fragmented DNA. | Key for identifying apoptotic cells via nuclear fragmentation. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) [35] [36] | Isotonic buffer for washing cells and diluting reagents. | Prevents osmotic shock and maintains pH. |

| Mounting Medium [38] | Preserves fluorescence and secures coverslip for imaging. | Avoid glycerol-based medium with some dyes; use buffer or antifade medium. |

Critical Steps and Troubleshooting

The relationship between key experimental steps and the final image quality is summarized below. Attention to detail at each stage prevents common artifacts.

Key Considerations:

- Fixative Compatibility: Methanol fixation is not recommended for subsequent staining with many membrane dyes or fluorescent proteins, as it can destroy epitopes or quench fluorescence [38] [36]. For nuclear fragmentation studies, PFA fixation is generally preferred.

- Mounting Medium: The choice of mounting medium is crucial. For original CellBrite dyes, CytoLiner stains, and similar, buffer-only mounting is recommended. Glycerol or solvent-based mounting media can dissolve or redistribute the stain, leading to loss of signal [38].

- Imaging Modality: For crisp imaging of cell boundaries and nuclear details, confocal microscopy is highly recommended over standard epifluorescence. Confocal microscopy rejects out-of-focus light, providing greater clarity and control over excitation power to limit photobleaching [38].

In fluorescence microscopy-based nuclear research, particularly in studies of nuclear fragmentation, the selection of appropriate fluorescent dyes and their corresponding microscope configuration is paramount. The blue fluorescent, nuclear-specific dyes DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) and Hoechst (including 33342 and 33258 variants) are fundamental tools for visualizing nuclear DNA [39] [6]. Both dyes exhibit minimal fluorescence in solution but become brightly fluorescent upon binding to the minor groove of DNA, with a distinct preference for A/T-rich regions [6]. This property enables specific nuclear staining with high signal-to-noise ratios. While their excitation and emission profiles are similar, with peak excitation in the ultraviolet (UV) to violet range (~358 nm for DAPI, ~350-352 nm for Hoechst) and emission around 461 nm, key differences influence their application [6]. Hoechst dyes are generally preferred for live-cell staining due to better cell permeability and lower toxicity, whereas DAPI is often favored for fixed cells as it is less cell-membrane permeant [6]. Understanding these characteristics is essential for configuring the microscope system to maximize signal detection while minimizing artifacts in nuclear fragmentation studies.

Microscope Configuration for DAPI/Hoechst

Filter Set Specifications

The core of detecting DAPI or Hoechst fluorescence lies in the epi-fluorescence filter cube. A standard setup includes an excitation filter, a dichromatic beamsplitter (mirror), and an emission (barrier) filter [40]. For DAPI/Hoechst, which are excited by UV light and emit blue light, a filter set designed for ultraviolet (UV) excitation is required.

Table 1: Recommended Filter Set Specifications for DAPI and Hoechst Staining

| Filter Component | Optimal Spectral Characteristics | Example Nikon Filter Cube & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Excitation Filter | Bandpass: 330-380 nm (Width: 10-50 nm) [40] | UV-2E/C: Sharp cutoff, narrow bandpass barrier to eliminate green/red background [40] |

| UV-1A: Narrow excitation bandpass; minimizes autofluorescence and photobleaching [40] | ||

| Dichromatic Mirror | Longpass: Cut-on at ~400 nm [40] | Cuts on wavelength aligns with the cut-off of the excitation bandpass [40] |

| Emission (Barrier) Filter | Bandpass: ~460-500 nm (e.g., 40 nm width) OR Longpass: >420 nm [40] | Bandpass: Isolates specific blue emission (e.g., UV-2E/C) [40] |

| Longpass: Allows detection of a wider blue range (e.g., UV-2A) [40] |

Objective Lens Selection

The choice of objective lens critically impacts resolution and signal collection efficiency. For high-resolution imaging of nuclear structures, including micronuclei and nuclear fragments, a high-numerical aperture (NA) plan-apochromatic objective is recommended. Plan Apo 60x/1.40 NA Oil or Plan Apo 40x/1.30 NA Oil objectives provide the necessary resolution and light-gathering capability. For lower magnification, wider field-of-view applications such as high-content screening, a Plan Fluor 20x/0.75 NA Air objective is a suitable and practical choice [41].

Camera and Detector Settings

sCMOS cameras are the current standard for high-sensitivity, low-noise quantitative imaging of DAPI and Hoechst fluorescence. Key settings must be optimized to detect the often-intense nuclear signal without saturation, which is crucial for accurate DNA content quantification [42].

- Gain: Use a unity or medium gain setting to maintain a high dynamic range and avoid introducing excessive read noise.

- Exposure Time: Begin with 50-200 ms and adjust based on signal intensity. Avoid saturation (pixels at maximum brightness) to ensure accurate integrated intensity measurements for cell cycle analysis [42].

- Bit Depth: A 16-bit camera is preferred over 12-bit to provide a greater dynamic range (65,536 vs. 4,096 grayscale levels), allowing for more precise quantification of intensity differences.

Experimental Protocols for Nuclear Staining

Live Cell Staining with Hoechst 33342

This protocol is designed for minimal perturbation of live cells and is ideal for tracking nuclear morphology in real-time.

Workflow: Live Cell Staining

Detailed Methodology:

- Dye Preparation: Prepare an intermediate 10X stock of Hoechst 33342 by diluting a concentrated aqueous solution (e.g., 10 mg/mL) into pre-warmed complete culture medium to a final concentration of 10 µg/mL [6].

- Staining: Without removing the medium from the cells, add one-tenth of the medium's volume of the 10X dye solution directly to the culture well. For example, add 100 µL of dye to 900 µL of medium in a well of a 24-well plate.

- Mixing: Immediately mix the medium thoroughly and gently by pipetting up and down or by gently swirling the plate to ensure even distribution of the dye and avoid localized high concentrations.

- Incubation: Incubate the cells for 5-15 minutes at either 37°C or room temperature, protected from light.