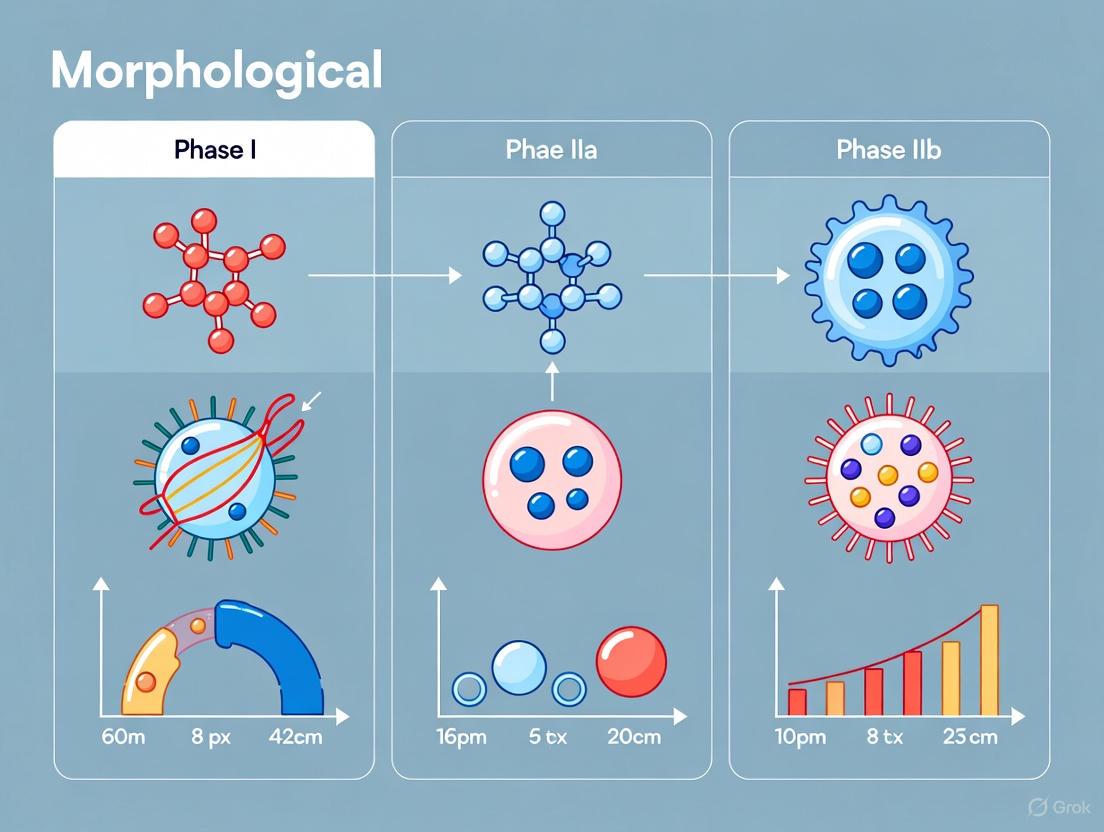

A Comprehensive Guide to the Morphological Features of Apoptosis Phases I, IIa, and IIb

This article provides a detailed examination of the distinct morphological characteristics that define Phase I (early), Phase IIa (middle), and Phase IIb (late) of apoptosis.

A Comprehensive Guide to the Morphological Features of Apoptosis Phases I, IIa, and IIb

Abstract

This article provides a detailed examination of the distinct morphological characteristics that define Phase I (early), Phase IIa (middle), and Phase IIb (late) of apoptosis. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it bridges foundational knowledge with practical application. The content systematically explores the ultrastructural changes observed via various microscopy techniques, compares methodological approaches for detection and analysis, addresses common challenges in morphological identification, and validates findings through integration with biochemical assays. This guide serves as a critical resource for accurately identifying and quantifying apoptotic progression in experimental and clinical contexts, ultimately informing therapeutic development.

Defining the Morphological Hallmarks of Apoptotic Phases I, IIa, and IIb

Apoptosis, a fundamental programmed cell death process, is characterized by a series of distinctive morphological and biochemical hallmarks that enable the controlled elimination of cells without inducing inflammation. This highly regulated process is crucial for multicellular organisms, playing essential roles in embryogenesis, tissue homeostasis, and the removal of damaged or potentially harmful cells [1] [2]. The execution of apoptosis occurs through specific signaling pathways—primarily the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways—that converge on the activation of caspases, which systematically dismantle cellular components [2]. Understanding the precise morphological features of apoptosis and their underlying molecular mechanisms has significant implications for therapeutic interventions in cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and autoimmune diseases. This technical review provides an in-depth analysis of apoptosis within the context of morphological research, detailing experimental methodologies, key regulatory networks, and essential research tools for investigating this critical cellular process.

Morphological Hallmarks of Apoptosis

The identification of apoptosis relies heavily on recognizing its characteristic morphological features, which distinguish it from other forms of cell death such as necrosis. These morphological changes occur in a coordinated sequence and can be observed through various microscopic techniques.

Core Morphological Characteristics

Table 1: Key Morphological Features of Apoptosis

| Morphological Feature | Description | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Shrinkage | Reduction in cell volume and cytoplasmic compaction | Light microscopy, electron microscopy |

| Chromatin Condensation | Chromatin aggregation into dense masses beneath nuclear membrane | Nuclear staining (DAPI, Hoechst), electron microscopy |

| Nuclear Fragmentation | Nuclear breakdown into discrete fragments (karyorrhexis) | Fluorescence microscopy, TUNEL assay |

| Membrane Blebbing | Formation of bulges on plasma membrane surface | Time-lapse microscopy, electron microscopy |

| Apoptotic Body Formation | Cell fragmentation into membrane-bound vesicles containing organelles | Electron microscopy, fluorescence microscopy |

| Phagocytosis | Engulfment of apoptotic bodies by neighboring cells | Histological analysis, time-lapse imaging |

The morphological process of apoptosis begins with cell shrinkage and chromatin condensation, where the nucleus undergoes pyknosis (condensation) and karyorrhexis (fragmentation) [1] [3]. This is followed by extensive plasma membrane blebbing and the separation of cell fragments into membrane-bound apoptotic bodies in a process called budding [3]. These apoptotic bodies contain intact organelles and are rapidly phagocytosed by macrophages, parenchymal cells, or neoplastic cells, subsequently degrading in phagolysosomes [1] [3]. Critically, this entire process occurs without inducing inflammation, as apoptotic cells do not release their cellular contents into the surrounding environment [3].

Contrasting Apoptosis and Necrosis

Table 2: Comparative Analysis: Apoptosis versus Necrosis

| Characteristic | Apoptosis | Necrosis |

|---|---|---|

| Distribution | Affects individual scattered cells | Affects massive contiguous cell groups |

| Cellular Morphology | Cell shrinkage, cytoplasmic compaction | Cell swelling, organelle disruption |

| Nuclear Changes | Chromatin condensation and margination | Irregular chromatin clumping, karyolysis |

| DNA Fragmentation | Internucleosomal cleavage (DNA ladder) | Random DNA degradation (smear pattern) |

| Membrane Integrity | Maintained until late stages | Lost early in the process |

| Inflammatory Response | Absent | Present |

| Energy Requirement | Energy-dependent, ATP-requiring | Energy-independent |

| Genomic Control | Genetically regulated | Not genetically controlled |

The distinction between apoptosis and necrosis is fundamental in cell death research. While apoptosis is a tightly regulated, energy-dependent process [3], necrosis is an uncontrolled, passive process typically resulting from acute cellular injury [2]. Morphologically, necrosis is characterized by cell swelling, formation of cytosolic vacuoles, distended endoplasmic reticulum, swollen or ruptured mitochondria, and eventual cell membrane disruption [3]. This membrane rupture results in the release of cytoplasmic contents into the surrounding environment, triggering inflammatory responses [3].

Molecular Mechanisms of Apoptosis

The morphological changes observed during apoptosis result from the precise activation and execution of molecular pathways. The two primary initiation routes are the extrinsic (death receptor) pathway and the intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathway, both culminating in the activation of caspases that execute the cell death program.

The Extrinsic Pathway

The extrinsic pathway is initiated by the binding of extracellular death ligands to their corresponding transmembrane death receptors, which belong to the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily [3]. Notable death ligands and receptors include FasL/FasR, TNF-α/TNFR1, Apo3L/DR3, and Apo2L/DR4/DR5 [3].

Upon ligand binding, the receptors undergo trimerization and recruit intracellular adapter proteins such as FADD (Fas-associated protein with death domain) through protein-protein interactions mediated by death domains [3]. This complex, known as the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC), recruits and activates initiator caspases (primarily caspase-8 and caspase-10) through proximity-induced autocatalytic cleavage [2] [3]. Active caspase-8 then activates executioner caspases (caspase-3, -6, and -7), which systematically cleave cellular substrates to bring about the morphological changes characteristic of apoptosis [2].

Diagram 1: Extrinsic apoptosis pathway activation

The Intrinsic Pathway

The intrinsic pathway, also known as the mitochondrial pathway, is triggered by intracellular stress signals such as DNA damage, oxidative stress, growth factor withdrawal, or endoplasmic reticulum stress [2]. These signals cause the Bcl-2 protein family to regulate mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) [1].

Pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins (such as Bax and Bak) oligomerize and form pores in the mitochondrial outer membrane, while anti-apoptotic members (including Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL) inhibit this process [2]. The permeabilization of the mitochondrial membrane leads to the release of several pro-apoptotic proteins from the intermembrane space into the cytosol, including cytochrome c and SMAC (second mitochondria-derived activator of caspases) [2].

Cytochrome c binds to Apaf-1 (apoptotic protease activating factor 1) and ATP to form the apoptosome, which recruits and activates procaspase-9 [2]. Active caspase-9 then activates the executioner caspases (primarily caspase-3). Simultaneously, SMAC proteins neutralize inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs), thereby relieving their suppression of caspase activity [2].

Diagram 2: Intrinsic apoptosis pathway mechanism

Caspase Activation and Execution

Both the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways converge on the activation of executioner caspases (primarily caspase-3, -6, and -7), which orchestrate the systematic dismantling of cellular structures [2]. Caspases are cysteine proteases that cleave their substrates after aspartic acid residues [3]. Their activation initiates a proteolytic cascade that amplifies the apoptotic signal and ensures rapid, irreversible commitment to cell death.

Executioner caspases target hundreds of cellular proteins, including:

- Nuclear proteins: Lamin proteins (nuclear envelope disintegration), ICAD/DFF45 (activation of DNases causing DNA fragmentation)

- Cytoskeletal proteins: Actin, fodrin, gelsolin (membrane blebbing and apoptotic body formation)

- DNA repair enzymes: Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP)

- Cell cycle regulators

- Cell adhesion molecules

This targeted proteolysis results in the characteristic morphological changes of apoptosis while maintaining membrane integrity to prevent inflammatory responses [1] [3].

Experimental Methods for Apoptosis Detection

Accurate detection and quantification of apoptosis are essential for research and therapeutic development. Multiple methodologies exist that target different aspects of the apoptotic process, from morphological assessment to biochemical and molecular analyses.

Morphological Assessment Techniques

Light and Electron Microscopy: The initial identification of apoptotic cells often relies on recognizing characteristic morphological changes using various microscopic techniques [3]. Light microscopy can reveal cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, and apoptotic body formation in stained tissue sections [3]. Electron microscopy provides higher resolution details, including organelle integrity, chromatin margination, and membrane blebbing [3].

Time-Lapse Microscopy: Live-cell imaging allows for the dynamic observation of apoptotic progression in real-time, including membrane blebbing, cell shrinkage, and apoptotic body formation [3].

Biochemical and Molecular Detection Methods

Table 3: Key Experimental Methods for Apoptosis Detection

| Method | Principle | Application | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TUNEL Assay | Detects DNA fragmentation by labeling 3'-OH ends | In situ detection of apoptotic cells in tissue sections | High sensitivity, works in fixed tissues | Can detect non-apoptotic DNA damage [1] |

| DNA Laddering | Agarose gel electrophoresis of fragmented DNA | Detection of internucleosomal DNA cleavage | Classic apoptosis confirmation | Requires many cells, not quantitative [1] |

| Caspase Activity Assays | Fluorogenic or colorimetric substrate cleavage | Measurement of caspase activation | Quantitative, specific to apoptosis | Does not indicate late-stage apoptosis |

| Annexin V Staining | Binds to phosphatidylserine externalized on membrane | Detection of early apoptotic stages | Distinguishes early vs late apoptosis | Requires live cells, confounded by necrosis |

| Mitochondrial Membrane Potential | Fluorescent dyes (JC-1, TMRM) | Assessment of mitochondrial integrity in intrinsic pathway | Early indicator of intrinsic apoptosis | Not specific to apoptosis alone |

| Western Blotting | Detection of cleavage products (PARP, caspases) | Confirmation of apoptotic protein activation | Specific, provides molecular evidence | Semi-quantitative, requires protein extraction |

The TUNEL (TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling) assay is a widely used method for detecting apoptotic cells in tissue samples by labeling the 3'-OH ends of fragmented DNA [1]. TUNEL-positive cardiomyocytes show morphological features of apoptosis and the typical ladder pattern in DNA electrophoresis [1]. However, careful standardization of the staining protocol is essential, as the assay can detect non-apoptotic DNA damage under suboptimal conditions [1].

Caspase activity assays utilize fluorogenic or colorimetric substrates that emit signals upon cleavage by active caspases, providing quantitative data on apoptotic progression [1]. These assays can be adapted for high-throughput screening of potential therapeutic compounds that modulate apoptosis.

Annexin V staining capitalizes on the externalization of phosphatidylserine during early apoptosis, which serves as an "eat-me" signal for phagocytes [3]. When combined with viability dyes like propidium iodide, this method can distinguish between early apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI-), late apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI+), and necrotic (Annexin V-/PI+) cells [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

The investigation of apoptotic mechanisms relies on a comprehensive toolkit of research reagents that enable the specific detection, modulation, and analysis of cell death pathways.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Apoptosis Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caspase Inhibitors | Z-VAD-FMK (pan-caspase inhibitor) | Inhibition of apoptotic execution | Irreversible binding to active site of caspases [4] |

| Death Receptor Ligands | Recombinant TNF-α, FasL, TRAIL | Extrinsic pathway activation | Binding to death receptors to initiate DISC formation [3] |

| Bcl-2 Family Modulators | ABT-737 (Bcl-2 inhibitor), AT-101 (Bcl-2/Bcl-xL inhibitor) | Modulating intrinsic pathway | Disrupting anti-apoptotic protein function [2] |

| IAP Antagonists | Smac mimetics (BV6) | Sensitizing cells to apoptosis | Neutralizing IAP proteins to promote caspase activation [5] [4] |

| Kinase Inhibitors | Cabozantinib (Met inhibitor), Necrostatin-1 (RIPK1 inhibitor) | Pathway-specific modulation | Targeting regulatory kinases in apoptotic signaling [4] |

| Mitochondrial Dyes | JC-1, TMRM, MitoTracker | Assessing mitochondrial health | Indicators of mitochondrial membrane potential [3] |

| Apoptosis Inducers | Staurosporine, Actinomycin D, Etoposide | Experimental induction of apoptosis | DNA damage or kinase inhibition [2] |

| Detection Antibodies | Anti-cleaved caspase-3, anti-PARP, anti-Bax | Immunodetection of apoptotic markers | Recognizing specific epitopes on apoptotic proteins [1] |

These research reagents enable precise investigation of apoptotic mechanisms and potential therapeutic interventions. For example, Smac mimetics are cytotoxic agents specifically designed to maximize tumor cell killing mediated via endogenous tumor necrosis factor (TNF) by targeting IAP proteins for degradation [4]. Similarly, caspase inhibitors like ZVAD allow researchers to distinguish between apoptotic and non-apoptotic cell death mechanisms and have been instrumental in identifying hybrid cell death processes [4].

Advanced Research Applications

Crosstalk Between Cell Death Mechanisms

Emerging research reveals extensive crosstalk between different cell death mechanisms, including apoptosis, autophagy, ferroptosis, necroptosis, mitophagy, and pyroptosis [6]. This crosstalk enables cells to integrate diverse stress signals and determine the most appropriate death modality based on cellular context, energy status, and environmental factors.

Key nodes in cell death crosstalk include:

- Caspase-8: Functions as a molecular switch between apoptosis and necroptosis

- Bcl-2 family proteins: Regulate both apoptosis and autophagy

- Mitochondrial integrity: Central to apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis

- Reactive oxygen species: Common inducers of multiple cell death pathways

Understanding these interconnections provides novel therapeutic opportunities, particularly for overcoming treatment resistance in cancer, where tumor cells often develop defects in apoptotic pathways [6] [4].

Computational Modeling of Apoptosis

Boolean or logical modeling has emerged as a promising approach to capture the qualitative behavior of complex apoptotic networks [5]. These models represent the apoptotic signaling network as a series of logical operations (ON/OFF states) that respond to various inputs such as Fas ligand, TNF-α, UV-B irradiation, and other stimuli [5].

Advanced Boolean models of apoptosis incorporate 86 nodes and 125 interactions, utilizing timescales and multi-value node logic to reproduce dynamic features such as threshold behavior, feedback loops, and reaction delays [5]. These computational approaches help identify critical regulatory hubs in the apoptotic network and predict cellular responses to combinatorial treatments, facilitating the development of selective control strategies for pathological conditions [7].

Therapeutic Targeting of Apoptosis Pathways

The precise regulation of apoptosis has significant therapeutic implications across multiple disease areas. In cancer, where apoptosis is often repressed, strategies focus on restoring or enhancing apoptotic sensitivity through:

- BH3 mimetics that inhibit anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins

- Smac mimetics that neutralize IAP-mediated caspase inhibition

- Death receptor agonists that directly activate extrinsic apoptosis

- Combination therapies that simultaneously target multiple regulatory nodes

Recent research demonstrates that targeting the Met-RIPK1 signaling axis with Cabozantinib can sensitize colorectal cancer cells to Smac mimetic-induced apoptosis and necroptosis, providing a promising approach to overcome therapy resistance [4]. Similarly, modulating between apoptosis and necroptosis represents a strategic approach to maximize tumor cell killing and foster anti-tumor immunity [4].

Apoptosis represents a critically important programmed cell death process characterized by distinctive morphological features that result from the precise execution of molecular pathways. The systematic investigation of apoptotic mechanisms—from initial morphological observations to current understanding of complex signaling networks—has provided fundamental insights into cellular homeostasis and disease pathogenesis. Advanced research methodologies, including sophisticated detection assays, targeted research reagents, and computational modeling approaches, continue to enhance our understanding of apoptotic regulation and its interconnections with other cell death modalities. This comprehensive knowledge base provides the foundation for developing novel therapeutic strategies that selectively modulate cell death pathways in cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and other pathological conditions, ultimately advancing the frontier of precision medicine.

Phase I (Early Apoptosis) represents the initial and commitment stage of programmed cell death, characterized by a defined set of morphological alterations that precede the complete dismantling of the cell. These early changes—cell shrinkage, cytoplasmic condensation, and loss of microvilli—serve as the first visible indicators that the apoptotic cascade has been irreversibly activated [8] [9]. This phase is distinct from accidental cell death (necrosis) and is tightly regulated by molecular machinery that transforms the cell's structure with remarkable precision [10]. The events of Phase I are not passive degenerative processes but are actively executed by proteases and other enzymes, setting the stage for subsequent phases involving nuclear fragmentation and the formation of apoptotic bodies [8].

Understanding these initial morphological hallmarks is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals. They provide a foundation for identifying apoptotic cells in experimental and clinical samples, from tissue sections to cell cultures, and are essential for validating the efficacy of therapies designed to modulate cell death, such as in cancer treatment [11]. This guide provides a detailed technical examination of the defining features, underlying mechanisms, and detection methodologies for Phase I apoptosis.

Morphological Hallmarks of Phase I Apoptosis

The transition of a cell into Phase I apoptosis involves a coordinated series of structural changes. The following table summarizes the core morphological features and their functional consequences.

Table 1: Core Morphological Features of Phase I Apoptosis

| Morphological Feature | Description | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Shrinkage | Reduction in cell volume and disruption of the cytoskeleton, leading to a smaller, more condensed cellular profile [8]. | Represents the initial break with normal cellular homeostasis and is a key feature distinguishing apoptosis from necrotic cell swelling [10]. |

| Cytoplasmic Condensation | Increased density of the cytoplasmic matrix and organelles, with the cell becoming deeply eosinophilic in stained preparations [8]. | Results from caspase-mediated cleavage of structural proteins and dehydration, concentrating the cellular contents. |

| Loss of Microvilli and Cell-Cell Contact | Breakdown of specialized surface structures, including microvilli, and detachment from neighboring cells and the extracellular matrix [8] [9]. | Facilitates the isolation of the dying cell from its healthy neighbors, a prelude to its eventual removal. |

The following diagram illustrates the temporal relationship and key signaling initiators of these morphological events during Phase I apoptosis:

Molecular Mechanisms and Key Players

The dramatic structural changes observed in Phase I are the direct result of the activation of caspases, a family of cysteine-aspartic proteases that act as the central executioners of apoptosis [8] [9]. Initiator caspases (e.g., caspase-8, -9) are activated upstream by either the extrinsic (death receptor) or intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathways. These, in turn, activate the executioner caspases-3, -6, and -7 [8] [10]. Caspase-3 is particularly crucial and targets several key structural proteins to initiate Phase I morphology:

- Cytoskeletal Disassembly: Caspase-3 cleaves proteins such as gelsolin, which then severs actin filaments, and ROCK1 kinase, which induces membrane blebbing by causing actomyosin contraction [9]. The breakdown of the cytoskeletal framework is the primary driver of cell shrinkage and the loss of structural integrity.

- Loss of Cell Adhesion: The cleavage of focal adhesion kinases (FAKs) and other adhesion complex proteins contributes to the loss of cell-cell and cell-matrix contacts, explaining the observed rounding and detachment of apoptotic cells [8].

Concurrently, one of the earliest biochemical events, which often precedes overt morphological changes, is the translocation of phosphatidylserine (PS) from the inner to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane [12]. This "eat-me" signal is recognized by phagocytic cells and is facilitated by the caspase-mediated inactivation of the flippase ATP11A and activation of the scramblase Xkr8 [9].

Table 2: Key Molecular Players in Phase I Apoptosis Morphology

| Molecule | Role/Function in Phase I | Effect on Morphology |

|---|---|---|

| Caspase-3 | Primary executioner caspase; cleaves numerous cellular substrates [9]. | Orchestrates multiple morphological changes including shrinkage, condensation, and membrane blebbing. |

| Gelsolin | Actin-binding protein; cleaved and activated by caspases [8]. | Severs actin filaments, leading to the dissolution of the cytoskeleton and cell shrinkage. |

| ROCK1 | Kinase regulating actomyosin contraction; cleaved and activated by caspases [9]. | Induces forceful contraction of the cell cortex, resulting in membrane blebbing. |

| Xkr8 / ATP11A | Plasma membrane phospholipid scramblase and flippase, respectively [9]. | Regulates phosphatidylserine externalization, a key "eat-me" signal for phagocytes. |

Experimental Detection and Analysis Protocols

Detecting Phase I apoptosis requires assays that capture the initial structural and membrane changes. A multi-modal approach is recommended for robust confirmation [8].

Light and Electron Microscopy

Protocol: Morphological Assessment via Microscopy

- Sample Preparation: Culture cells or collect tissue samples. Induce apoptosis using a relevant stimulus (e.g., staurosporine, chemotherapeutic agent, UV irradiation). Fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde [10].

- Staining:

- Analysis: Examine slides under a light microscope. Apoptotic cells are identified by their reduced size, condensed cytoplasm, and nuclear changes (chromatin condensation) [8]. For higher resolution, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) can be used to confirm organelle condensation and loss of microvilli [9].

Annexin V Staining for Phosphatidylserine Exposure

Protocol: Flow Cytometry for Early Apoptosis

- Cell Harvesting: Gently harvest adherent cells using a non-enzymatic dissociation buffer to preserve membrane integrity [12].

- Staining:

- Incubation and Analysis: Incubate cells for 15-20 minutes in the dark. Analyze immediately using a flow cytometer.

- Early Apoptotic Cells: Annexin V positive / PI negative.

- This assay is a cornerstone for quantifying cells in the early stages of apoptosis [12].

Analysis of Caspase Activation

Protocol: Immunoblotting for Caspase-3 Cleavage

- Protein Extraction: Lyse control and treated cells in RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors.

- Electrophoresis and Transfer: Separate proteins via SDS-PAGE (12-15% gel) and transfer to a nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane.

- Immunodetection:

- Block membrane with 5% non-fat milk.

- Probe with a primary antibody against cleaved caspase-3 (preferable) or total caspase-3.

- Incubate with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and detect using chemiluminescence [10].

- Expected Result: Appearance of a lower molecular weight band (~17/19 kDa) corresponding to the active subunits of caspase-3 in apoptotic samples, confirming the activation of the executioner phase [8].

The following workflow diagram integrates these key methodologies into a coherent experimental strategy:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

A range of well-characterized reagents is critical for the experimental investigation of Phase I apoptosis. The following table details essential tools and their applications.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Phase I Apoptosis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Viability & Membrane Assays | Annexin V (FITC, PE conjugates); Propidium Iodide (PI); 7-AAD | Detects phosphatidylserine exposure and loss of membrane integrity to distinguish early and late apoptotic stages via flow cytometry [8] [12]. |

| Caspase Activity Assays | Fluorogenic substrates (e.g., DEVD-AFC for caspase-3); Caspase inhibitors (e.g., Z-VAD-FMK) | Measures enzymatic activity of caspases for proof of apoptotic mechanism; inhibitors confirm caspase-dependency of observed death [8]. |

| Antibodies for Immunoassay | Anti-cleaved caspase-3; Anti-cytochrome c; Anti-Bcl-2 family proteins | Used in Western blot (WB) and Immunohistochemistry (IHC) to detect activation of key apoptotic proteins and regulators [12] [10]. |

| DNA-Binding Dyes | Hoechst 33342; DAPI; Acridine Orange | Stain condensed chromatin in apoptotic nuclei for visualization by fluorescence microscopy [8]. |

| Inducers/Inhibitors | Staurosporine; TRAIL; ABT-263 (Navitoclax); TNF-α | Pharmacological tools to reliably induce apoptosis (intrinsic/extrinsic pathways) or inhibit specific anti-apoptotic proteins (e.g., Bcl-2) for experimental control [13] [11]. |

The events of Phase I apoptosis—cell shrinkage, cytoplasmic condensation, and loss of microvilli—are the definitive morphological signature of a cell undergoing programmed demolition. These changes are not passive but are actively driven by the precise cleavage of structural proteins by activated caspases. Mastery of the assays to detect these changes, from Annexin V staining to caspase immunoblotting, is fundamental for research in cell biology, toxicology, and drug development. As therapeutic strategies increasingly aim to modulate apoptosis, particularly in oncology [11], a rigorous understanding of this initial phase provides the critical framework for analyzing therapeutic efficacy and understanding resistance mechanisms.

Within the broader morphological framework of apoptosis, cell death progresses through three distinct nuclear phases: Phase I (chromatin condensation and cell shrinkage), Phase IIa (nuclear collapse characterized by pyknosis and chromatin margination), and Phase IIb (nuclear fragmentation into apoptotic bodies) [14]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of Phase IIa apoptosis, a critical middle stage marked by definitive nuclear collapse. During this stage, the cell commits to the point of no return in the death pathway [14]. We will delineate the characteristic morphological features of Phase IIa, detail the molecular mechanisms driving these changes, and present robust experimental protocols for its detection and quantification. A thorough understanding of this phase is paramount for basic cell biology research and for the development of therapeutics designed to induce or inhibit cell death in diseases such as cancer [15].

Morphological and Nuclear Characteristics of Phase IIa Apoptosis

Phase IIa represents the stage of nuclear collapse and disassembly, serving as a bridge between the initial condensation of Phase I and the final packaging of cellular contents into apoptotic bodies in Phase IIb [14]. The defining morphological characteristics of this stage are profound and observable at the ultrastructural level.

The most prominent feature is chromatin condensation, where the nuclear chromatin becomes densely packed [6]. This is closely followed by pyknosis, the irreversible condensation of the nuclear chromatin resulting in a reduction of nuclear size and increased basophilia, and nuclear margination, a process where the condensed chromatin aggregates along the inner periphery of the nuclear membrane [14] [15]. Concurrently, the cell itself continues to shrink and undergoes a process of budding, and the cytoskeleton begins to degrade [14]. It is critical to note that the integrity of the plasma membrane is maintained throughout this phase, preventing the release of intracellular contents and an inflammatory response, which distinguishes apoptosis from necrotic cell death [14] [6].

Table 1: Key Morphological Characteristics of Apoptosis Phase IIa

| Feature | Description | Technical Observation Method |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatin Condensation | Chromatin becomes highly compacted and densely stained. | Electron microscopy; Fluorescence microscopy (DAPI/Hoechst) [14] |

| Pyknosis | Irreversible condensation of nuclear chromatin, leading to a small, dense nucleus. | Light microscopy (HE staining); Fluorescence microscopy [15] |

| Nuclear Margination | Condensed chromatin aggregates on the inner nuclear membrane. | Electron microscopy; Fluorescence microscopy [14] |

| Nuclear Shrinkage | Overall reduction in nuclear volume. | Computerized morphometric analysis of stained nuclei [15] |

| Intact Plasma Membrane | Cellular membrane remains intact, preventing inflammatory response. | Exclusion dyes (e.g., Propidium Iodide) in live cells [14] |

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The dramatic nuclear morphology of Phase IIa is executed by a tightly regulated molecular cascade, primarily driven by the activation of caspases and specific endonucleases.

Caspase Activation and Substrate Cleavage

The apoptotic process, including the transition to Phase IIa, is dependent on the activation of a family of cysteine proteases known as caspases [16]. These exist as inactive zymogens in healthy cells and are cleaved and activated in a cascade. Both the intrinsic (mitochondrial) and extrinsic (death receptor) pathways converge on the activation of executioner caspases, such as caspase-3 and caspase-7 [17] [6]. Once activated, these caspases cleave a wide array of intracellular substrates, including structural proteins of the nucleus and cytoskeleton, which facilitates the morphological changes characteristic of apoptosis [17].

The Role of DFF40/CAD Endonuclease in Chromatin Collapse

A key substrate of caspase-3 is DFF45/ICAD (Inhibitor of Caspase-Activated DNase), the chaperone and inhibitor of the endonuclease DFF40 (also known as CAD) [16]. Cleavage of DFF45/ICAD leads to the release and activation of DFF40/CAD [16]. While this endonuclease is famously known for hydrolyzing DNA into oligonucleosomal-sized fragments (the DNA ladder), research indicates that its role in Phase IIa nuclear collapse is distinct.

Studies using cell models that undergo caspase-dependent apoptosis without DNA laddering have shown that DFF40/CAD is still essential for the chromatin compaction and nuclear disassembly of Phase IIa [16]. The mechanism involves DFF40/CAD generating single-strand DNA nicks/breaks (SSBs) with 3'-OH ends, rather than the double-strand breaks responsible for the DNA ladder [16]. This specific type of DNA damage is sufficient to prompt the highest order of chromatin compaction observed in Stage II apoptotic nuclei. Therefore, Phase IIa chromatin collapse relies on DFF40/CAD-mediated DNA damage, with the nature of the DNA break being a critical factor.

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular events leading to Phase IIa morphology:

Experimental Protocols for Detection and Analysis

Accurate identification and quantification of Phase IIa apoptosis require a combination of morphological, biochemical, and cytometric techniques. Below are detailed protocols for key methodologies.

Fluorescence Microscopy and Nuclear Morphometry

This protocol allows for the quantitative assessment of apoptotic nuclear changes, including pyknosis and shrinkage [15].

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Induction: Seed cells (e.g., LNCaP or MDA-MB-231) onto culture dishes or multi-well plates and allow them to adhere. Treat with an apoptosis-inducing agent (e.g., 3.0 μM Cycloheximide) for a predetermined time (e.g., 24 hours) [15].

- Fixation and Permeabilization: Wash cells twice with Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS). Permeabilize cells by incubating with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10-15 minutes at room temperature [15].

- Nuclear Staining: Wash cells with PBS. Incubate with a nuclear stain, such as 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) at a concentration of 1.0 μg/ml, for 10-20 minutes protected from light [15].

- Image Acquisition: Using a fluorescence microscope (e.g., Keyence BZ-9000), acquire images from multiple random fields using a DAPI filter set with a 20x or higher magnification objective [15].

- Morphometric Analysis: Use image analysis software (e.g., BZ II Analyzer) to quantify parameters for each nucleus. Key parameters include:

- Area: The total area of the nucleus (μm²). Apoptotic nuclei show a significant decrease.

- Perimeter: The outer boundary length of the nucleus (μm).

- Major and Minor Axis: The longest and shortest diameter of the nucleus (μm).

- Brightness: The mean fluorescence intensity. Apoptotic nuclei often show increased brightness due to chromatin condensation [15].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Phase IIa Apoptosis Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| DAPI / Hoechst 33258 | Fluorescent DNA dyes that bind preferentially to A-T regions, staining the nucleus. | Visualization of nuclear morphology (condensation, pyknosis) via fluorescence microscopy [15]. |

| Cycloheximide (CHX) | Inhibitor of protein synthesis; a potent activator of apoptotic pathways. | Used as a positive control inducer of apoptosis in model cell lines [15]. |

| Caspase Inhibitor (e.g., Q-VD-OPh) | Pan-caspase inhibitor that prevents the activation of executioner caspases. | Tool to confirm the caspase-dependence of the observed nuclear morphology [16]. |

| Anti-DFF40/CAD Antibody | Specific antibody for immunoblotting or immunofluorescence. | Used to detect the expression and cleavage/activation status of the DFF40/CAD endonuclease [16]. |

| TUNEL Assay Kit | Labels 3'-OH ends of DNA fragments with fluorescent tags. | Detects the DNA strand breaks generated during apoptosis, including those in Phase IIa [16] [15]. |

In Situ Detection of DNA Strand Breaks (TUNEL Assay)

The TUNEL (TdT dUTP Nick-End Labeling) assay is a key method for detecting the 3'-OH DNA ends generated by DFF40/CAD and other nucleases during apoptosis [16].

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation and Fixation: Culture and induce apoptosis in cells grown on glass coverslips. Fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15-30 minutes at room temperature.

- Permeabilization: Permeabilize the fixed cells with a mild detergent (e.g., 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 5-10 minutes on ice to allow enzyme access to the nucleus.

- Labeling Reaction: Prepare the TUNEL reaction mixture containing Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase (TdT) and fluorescently-labeled dUTP (e.g., FITC-dUTP). Incubate the coverslips with the reaction mixture in a humidified chamber for 60 minutes at 37°C in the dark.

- Counterstaining and Mounting: Wash the coverslips thoroughly to remove unincorporated nucleotides. Counterstain the nuclei with DAPI or Hoechst to visualize all cells.

- Analysis: Mount the coverslips and analyze by fluorescence microscopy. Cells with positive TUNEL staining (green fluorescence) indicate the presence of DNA strand breaks, a hallmark of mid-to-late stage apoptosis. It is crucial to include appropriate controls (e.g., DNase-treated cells as a positive control, and omission of TdT enzyme as a negative control) [14] [16].

Discriminating Apoptosis from Necrosis in Real-Time

Advanced live-cell imaging techniques can dynamically distinguish Phase IIa apoptosis from necrotic cell death, which is vital for understanding drug mechanisms.

Procedure Utilizing FRET-Based Caspase Sensor:

- Stable Cell Line Generation: Engineer a cell line (e.g., U251 neuroblastoma) to stably express two constructs: a soluble FRET-based caspase sensor (e.g., ECFP-DEVD-EYFP) and a non-soluble organelle-targeted fluorescent protein (e.g., Mito-DsRed) [18].

- Real-Time Imaging: Treat the cells with the compound of interest and perform time-lapse imaging using a fluorescence microscope equipped with environmental control (37°C, 5% CO₂).

- Data Interpretation:

- Viable Cells: Exhibit intact FRET (yellow emission) and mitochondrial red fluorescence.

- Apoptotic Cells (Phase IIa): Show a loss of FRET (increase in blue donor emission) due to caspase-mediated cleavage of the DEVD linker, while retaining mitochondrial DsRed fluorescence.

- Necrotic Cells: Lose the soluble FRET probe completely (no ECFP or EYFP signal) due to membrane rupture, while initially retaining the mitochondrial DsRed signal [18].

The experimental workflow for a multi-method approach to characterizing Phase IIa apoptosis is summarized below:

Phase IIa apoptosis, characterized by chromatin condensation, pyknosis, and nuclear margination, represents a decisive commitment to cell death driven by caspase-3 and the DFF40/CAD-mediated generation of single-strand DNA breaks. A comprehensive approach, utilizing the quantitative and qualitative methods detailed in this guide, is essential for researchers to accurately identify and study this critical phase. As our understanding of the molecular crosstalk between different cell death pathways deepens [6], the precise characterization of apoptotic stages will become increasingly important for developing more effective and targeted therapeutic strategies, particularly in oncology and neurodegenerative diseases.

Phase IIb, or late apoptosis, represents the terminal executive phase of the programmed cell death process, characterized by systematic cellular disintegration. This phase follows the initial signaling events and early morphological changes, culminating in the hallmark features of nuclear fragmentation and apoptotic body formation [17] [19]. These structural changes represent the irreversible commitment to cell death and facilitate the safe packaging and removal of cellular debris without eliciting an inflammatory response, distinguishing apoptosis from necrotic cell death [17] [13].

The biological significance of these late-stage events lies in their role in maintaining tissue homeostasis. By efficiently disposing of unwanted cells through phagocytosis by neighboring cells or professional phagocytes, apoptosis prevents the release of intracellular contents that could trigger inflammation or autoimmune reactions [6] [13]. This silent elimination is particularly crucial during developmental processes, tissue remodeling, and the elimination of damaged or potentially harmful cells [19].

Morphological Hallmarks of Phase IIb

Nuclear Fragmentation

Nuclear fragmentation, also known as karyorrhexis, involves the systematic breakdown of the nucleus into discrete, membrane-bound fragments. This process begins with chromatin condensation, where nuclear chromatin aggregates into dense, marginalized masses against the nuclear envelope [17] [19]. The nuclear envelope then invaginates and fragments, followed by the separation of the condensed chromatin into multiple discrete nuclear bodies [17].

This nuclear disintegration is mediated by the activation of specific endonucleases, particularly caspase-activated DNase (CAD), which cleaves DNA at internucleosomal regions, producing characteristic DNA fragments in multiples of approximately 180-200 base pairs [19]. This cleavage pattern results in the distinctive DNA laddering pattern observed in gel electrophoresis, which serves as a biochemical hallmark of apoptosis [19].

Apoptotic Body Formation

Following nuclear disintegration, the cell undergoes a coordinated process of segmentation into apoptotic bodies. The cell membrane undergoes pronounced blebbing, forming protrusions that eventually separate from the main cell body [20] [19]. These membrane-bound vesicles typically range from 0.5 to 2.0 micrometers in diameter and contain various cellular components, including intact organelles, nuclear fragments, and cytoplasmic elements [17].

Critically, during this process, phosphatidylserine—a phospholipid normally restricted to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane—translocates to the external surface of the apoptotic bodies [17]. This surface alteration serves as an "eat me" signal for phagocytic cells, facilitating the recognition and clearance of the apoptotic debris [17] [19]. The entire process occurs without compromising plasma membrane integrity, thus preventing the release of pro-inflammatory intracellular components [13].

Table 1: Key Morphological Features of Phase IIb Apoptosis

| Morphological Feature | Description | Molecular Mediators | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatin Condensation | Aggregation of nuclear chromatin into dense, marginalized masses | Histone modification, caspase activation | Inactivates genetic material, initiates nuclear breakdown |

| Nuclear Fragmentation | Disintegration of nucleus into multiple discrete fragments | Caspase-activated DNase (CAD), Lamin cleavage | Packages nuclear material for disposal |

| DNA Fragmentation | Cleavage at internucleosomal regions | Endonucleases | Produces characteristic DNA laddering pattern |

| Membrane Blebbing | Protrusion and bulging of plasma membrane | ROCK1-mediated actin cytoskeleton reorganization | Facilitates cell segmentation |

| Apoptotic Body Formation | Formation of membrane-bound vesicles containing cellular components | Cytoskeletal breakdown, membrane remodeling | Packages cellular contents for phagocytosis |

| Phosphatidylserine Externalization | Translocation to outer membrane leaflet | Scramblase activation, floppase inhibition | Promotes recognition by phagocytic cells |

Quantitative Analysis of Morphological Changes

Advanced imaging technologies have enabled precise quantification of the morphological alterations characterizing late apoptosis. Studies utilizing high-resolution techniques like Full-Field Optical Coherence Tomography (FF-OCT) have documented consistent dimensional changes during this phase [20].

Cells undergoing late apoptosis demonstrate a significant reduction in cell volume—typically decreasing to 40-60% of their original size—as the cytoplasm condenses and organelles are packaged into apoptotic bodies [20]. The nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio also decreases dramatically as the nucleus fragments and disperses. Time-lapse imaging reveals that the process from initial nuclear condensation to complete apoptotic body formation typically occurs within 30-180 minutes, depending on cell type and apoptotic stimulus [20].

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters of Late Apoptosis Morphology

| Parameter | Measurement Method | Typical Values in Late Apoptosis | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Volume Reduction | FF-OCT 3D topography | 40-60% of original volume | Measured via surface reconstruction |

| Apoptotic Body Size | Electron microscopy, FF-OCT | 0.5-2.0 μm diameter | Membrane-bound vesicles |

| Nuclear Condensation | Chromatin staining intensity | 2-3 fold increase in density | DAPI/Hoechst fluorescence |

| DNA Fragmentation | Gel electrophoresis | 180-200 bp multiples | "DNA laddering" pattern |

| Time Course | Live-cell imaging | 30-180 minutes | Cell type and stimulus dependent |

| Phosphatidylserine Exposure | Annexin V binding | >80% of cells | Detected before membrane permeability |

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The morphological changes of Phase IIb apoptosis are executed through the coordinated activation of specific molecular pathways. The caspase cascade serves as the central executioner, with initiator caspases (caspase-8, -9) activating effector caspases (caspase-3, -6, -7) that directly cleave cellular structural proteins [6] [17] [19].

Nuclear Disassembly Mechanisms

Nuclear fragmentation is mediated through the caspase-mediated cleavage of key nuclear structural proteins. Lamin proteins, which form the nuclear lamina scaffolding, are cleaved by caspase-6, leading to the collapse of the nuclear envelope integrity [17]. Simultaneously, activation of caspase-activated DNase (CAD) through cleavage of its inhibitor (ICAD) by caspase-3 results in DNA fragmentation at internucleosomal sites [19]. Additional caspase targets include proteins involved in DNA repair (such as PARP) and nuclear transport, ensuring the systematic dismantling of nuclear function and structure [6].

Cytoskeletal Reorganization and Membrane Blebbing

The dramatic changes in cell shape and the formation of apoptotic bodies are driven by caspase-mediated cleavage of cytoskeletal components. Caspase-3 cleaves ROCK1, generating a constitutively active fragment that induces hyperphosphorylation of myosin light chain, leading to actomyosin contraction and membrane blebbing [20]. Additionally, cleavage of gelsolin by caspase-3 produces an active fragment that severs actin filaments, contributing to cytoskeletal collapse [17]. Other structural proteins targeted include fodrin, paxillin, and focal adhesion kinases, which disrupts cell-matrix and cell-cell contacts, facilitating cell detachment and rounding [19].

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular events in Phase IIb apoptosis:

Experimental Models and Detection Methodologies

Induction Models for Late Apoptosis

Researchers employ various models to induce and study late apoptosis. Doxorubicin treatment (typically 5 μmol/L for HeLa cells) effectively triggers the intrinsic apoptotic pathway by intercalating into DNA and inhibiting topoisomerase II, causing DNA double-strand breaks and p53 activation [20]. The extrinsic pathway can be activated using death receptor ligands such as Fas ligand or TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) at concentrations ranging from 10-100 ng/mL, depending on cell sensitivity [6] [21]. For cellular stress induction, reactive oxygen species inducers like hydrogen peroxide (100-500 μmol/L) or compounds that disrupt mitochondrial membrane potential are frequently utilized [22].

Detection and Imaging Techniques

Multiple complementary approaches are employed to detect and quantify Phase IIb apoptotic features:

Microscopy Techniques: Full-Field Optical Coherence Tomography (FF-OCT) provides label-free, high-resolution (sub-micrometer) visualization of apoptotic morphological changes, including membrane blebbing and apoptotic body formation in living cells [20]. Electron microscopy remains the gold standard for detailed ultrastructural analysis of nuclear condensation and organelle packaging in apoptotic bodies [17]. Fluorescence microscopy using DNA-binding dyes (DAPI, Hoechst) reveals nuclear fragmentation, while Annexin V conjugates detect phosphatidylserine externalization [17] [19].

Biochemical Assays: DNA laddering analysis via agarose gel electrophoresis detects the characteristic internucleosomal DNA cleavage pattern [19]. The TUNEL assay (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP Nick-End Labeling) enzymatically labels the 3'-ends of DNA fragments, allowing in situ detection and quantification of DNA fragmentation [17]. Caspase activity assays using fluorogenic or colorimetric substrates confirm the activation of the executioner caspases, particularly caspase-3 [19].

The following workflow outlines a comprehensive experimental approach for studying late apoptosis:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Phase IIb Apoptosis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application/Function | Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apoptosis Inducers | Doxorubicin (5 μmol/L), Anti-Fas antibody, TRAIL (10-100 ng/mL), Staurosporine (0.1-1 μmol/L) | Trigger specific apoptotic pathways | Viability assays, morphology analysis |

| Caspase Substrates | Ac-DEVD-AMC (caspase-3), Ac-IETD-AFC (caspase-8), Ac-LEHD-AFC (caspase-9) | Measure caspase activity | Fluorometry, spectrophotometry |

| Nuclear Stains | DAPI, Hoechst 33342, Propidium Iodide | Visualize chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation | Fluorescence microscopy |

| Phosphatidylserine Detection | FITC-Annexin V, Cy5-Annexin V | Detect PS externalization on apoptotic bodies | Flow cytometry, microscopy |

| DNA Fragmentation Kits | TUNEL assay kits, DNA laddering extraction kits | Detect and quantify DNA breakdown | Fluorescence microscopy, gel electrophoresis |

| Caspase Inhibitors | Z-VAD-FMK (pan-caspase), Z-DEVD-FMK (caspase-3) | Confirm caspase-dependent mechanisms | Control experiments |

| Structural Protein Antibodies | Anti-lamin A/C, Anti-PARP, Anti-ROCK1 | Detect cleavage of specific substrates | Western blot, immunofluorescence |

Technical Considerations and Research Applications

Methodological Considerations

When studying Phase IIb apoptosis, several technical considerations are crucial for accurate interpretation. Kinetic monitoring is essential, as late apoptotic events represent a transient state that quickly progresses to secondary necrosis if apoptotic bodies are not cleared [20]. Employing multiple complementary detection methods is recommended, as reliance on a single parameter may yield false positives or negatives; for instance, Annexin V staining alone cannot distinguish between early and late apoptosis [17] [19].

The cell type and apoptotic stimulus significantly influence the morphological presentation and timing of late apoptotic events [20]. Additionally, researchers must consider that phagocytic clearance of apoptotic bodies occurs rapidly in vivo, making their detection more challenging in physiological contexts compared to in vitro systems [6] [13].

Research and Therapeutic Applications

Understanding Phase IIb apoptosis has significant implications for both basic research and therapeutic development. In drug discovery and screening, compounds that induce or enhance late apoptotic events are valuable candidates for cancer therapeutics, particularly for tumors resistant to conventional treatments [13] [19]. Quantitative assessment of nuclear fragmentation and apoptotic body formation serves as a key efficacy metric for evaluating novel chemotherapeutic agents [20] [23].

In toxicology and safety assessment, unintended induction of late apoptosis indicates compound toxicity, informing risk assessment [20]. Furthermore, dysregulated apoptotic body clearance is implicated in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, making the morphological assessment of late apoptosis relevant for understanding disease mechanisms [6] [13]. The distinctive morphological features also provide important diagnostic markers in histopathology for distinguishing apoptotic cells from those undergoing other forms of cell death [17].

The Critical Role of Phagocytosis in Clearing Apoptotic Bodies without Inflammation

The efficient clearance of apoptotic cells is a fundamental biological process essential for maintaining tissue homeostasis and preventing inflammatory responses. This intricate process, known as efferocytosis, involves specialized mechanisms that allow phagocytes to recognize, engulf, and process dying cells without triggering the release of pro-inflammatory mediators. Understanding the molecular pathways governing this silent disposal system provides crucial insights into tissue remodeling, resolution of inflammation, and the prevention of autoimmune disorders. This technical review examines the sophisticated cellular and molecular machinery that enables the non-inflammatory clearance of apoptotic bodies, with particular emphasis on the morphological transitions during apoptosis and their implications for phagocytic recognition.

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is a genetically controlled process that eliminates unwanted or damaged cells during development, tissue homeostasis, and immune responses. In adult humans, an estimated one million cells undergo apoptosis every second, requiring an efficient clearance mechanism to prevent the accumulation of cellular debris [24]. The specific phagocytosis of dying cells by macrophages, termed efferocytosis, represents a critical mechanism for maintaining tissue integrity and preventing autoimmune reactions [25]. Unlike necrotic cell death, which results in membrane rupture and release of inflammatory contents, apoptosis produces membrane-bound fragments known as apoptotic bodies that are safely disposed of through phagocytic uptake.

The immunological consequences of apoptotic cell clearance are profoundly different from those following pathogen phagocytosis. While both processes may engage similar receptors, efferocytosis typically promotes an anti-inflammatory response and immunological tolerance rather than inflammation and immunity [26]. This review systematically examines the morphological features of apoptotic cells, the molecular recognition systems, and the intracellular processing mechanisms that collectively enable the non-inflammatory clearance of apoptotic bodies, with specific focus on their implications for research and therapeutic development.

Morphological Transitions During Apoptosis and Phagocytic Implications

The morphological progression of apoptosis creates distinct cellular states that directly influence how phagocytes recognize and engulf dying cells. These structural changes have been categorized into three sequential phases, each characterized by specific alterations that facilitate efficient clearance.

Table 1: Morphological Characteristics of Apoptotic Phases and Their Impact on Clearance

| Apoptotic Phase | Key Morphological Features | Detection Methods | Impact on Phagocytic Clearance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I | Cell shrinkage, dense cytoplasm, decreased water content, increased eosinophilia, disappearance of microvilli | Electron microscopy, membrane permeability assays | Initial "find-me" signal release, early recognition marker exposure |

| Phase IIa | Chromatin condensation (pyknosis), marginalization along nuclear membrane, nuclear fragmentation | Fluorescence microscopy (Hoechst, DAPI, AO), TUNEL assay | Exposure of "eat-me" signals including phosphatidylserine |

| Phase IIb | Membrane blebbing, cytoskeleton degradation, apoptotic body formation | Light microscopy (HE, Giemsa, Wright's staining), FCM | Generation of bite-sized fragments for phagocytosis, maximal "eat-me" signal display |

Phase I: Initial Activation and Cell Shrinkage

During Phase I, apoptotic cells undergo cytoplasmic condensation and reduced volume while maintaining membrane integrity. The cytoplasm becomes increasingly dense with organelle compaction, and surface structures such as microvilli retract [14]. These changes are mediated by caspase activation and cytoskeletal reorganization. From a clearance perspective, this phase is characterized by the initial release of soluble "find-me" signals including nucleotides (ATP and UTP) and lipids (lysophosphatidylcholine) that attract potential phagocytes to the dying cell [25] [24].

Phase IIa: Nuclear Fragmentation

Phase IIa is defined by nuclear disintegration featuring highly condensed chromatin masses (pyknosis) that subsequently marginalize along the inner nuclear membrane [14]. This stage involves the activation of endogenous endonucleases that cleave DNA at internucleosomal sites, producing characteristic fragments of 180-200 base pairs [14]. Detection methods for this phase include fluorescence microscopy with DNA-binding dyes (Hoechst 33342, DAPI) that reveal chromatin condensation, and TUNEL assays that identify DNA strand breaks with 3'-OH ends [14]. The nuclear breakdown during Phase IIa coincides with the externalization of phosphatidylserine (PS) on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, serving as a primary "eat-me" signal for phagocytes [26].

Phase IIb: Apoptotic Body Formation

The terminal Phase IIb features extensive membrane blebbing and the formation of apoptotic bodies containing nuclear debris, organelles, and cytoplasmic components [14]. This process is mediated by ROCK1 (Rho-associated protein kinase 1) activation following caspase-3 cleavage, leading to actomyosin contraction and membrane protrusion [27]. The resulting apoptotic bodies range from 50-5000 nm in diameter and present an optimal "bite-size" for phagocytic engulfment [27]. These membrane-bound vesicles display the full complement of "eat-me" signals, including surface-exposed phosphatidylserine, calreticulin, and other apoptotic cell-associated molecular patterns (ACAMPs) that facilitate recognition by professional phagocytes [26] [28].

Diagram 1: Morphological Transitions During Apoptosis and Phagocytic Clearance. This flowchart illustrates the sequential phases of apoptosis and their relationship to phagocytic recognition mechanisms.

Molecular Recognition Systems in Efferocytosis

The precise recognition of apoptotic cells involves a sophisticated network of signaling molecules, receptors, and bridging proteins that distinguish dying cells from their viable counterparts. This molecular machinery ensures the selective removal of apoptotic bodies while maintaining immune silence.

Find-Me Signals and Phagocyte Recruitment

Apoptotic cells release chemoattractant signals that recruit potential phagocytes before the loss of membrane integrity. These "find-me" signals include:

- Nucleotides (ATP and UTP): Released through pannexin 1 channels and detected by phagocyte P2Y2 receptors [25] [24]

- Lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC): Generated by caspase-3 activation of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2) and recognized by G2A receptors on macrophages [25] [24]

- Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P): Promotes monocyte and macrophage migration through G protein-coupled receptors [25]

- Fractalkine (CX3CL1): Present on apoptotic microparticles and engages CX3CR1 on phagocytes [24]

These find-me signals operate at picomolar to nanomolar concentrations and establish a chemotactic gradient that guides phagocytes to apoptotic cells without provoking inflammatory responses [24].

Eat-Me Signals and Phagocytic Receptors

The specific recognition of apoptotic cells is mediated through "eat-me" signals that are absent from viable cells. The most characterized eat-me signal is phosphatidylserine (PS), a phospholipid normally restricted to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane by ATP-dependent translocases [26]. During apoptosis, PS becomes externalized through caspase-activated scramblase activity and translocase inhibition [26]. Phagocytes recognize PS through multiple receptor systems:

Table 2: Principal Phagocytic Receptors and Recognition Mechanisms in Efferocytosis

| Receptor Category | Specific Receptors | Recognition Mechanism | Signaling Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct PS Receptors | TIM-1, TIM-4, BAI1, Stabilin-2 | Direct binding to phosphatidylserine | BAI1: ELMO1-Dock180-Rac module; TIM-4: Requires adaptor for signaling |

| Bridging Molecule Receptors | Integrins (αvβ3, αvβ5), TAM receptors (Tyro3, Axl, Mer) | Bind opsonins (MFG-E8, Gas6, Protein S) that recognize PS | Integrins: Focal adhesion kinase; TAM receptors: Tyrosine kinase signaling |

| Scavenger Receptors | CD36, SR-A, LOX-1 | Recognize oxidized PS and other modified lipids | Src family kinases, Rho GTPases |

| Complement Receptors | CD91 (LRP1), C1q receptors | Bind complement proteins (C1q, C3b) that opsonize apoptotic cells | MAPK/ERK signaling |

The TAM receptor family (Tyro3, Axl, Mer) represents a particularly important recognition system that binds the bridging molecules Gas6 and Protein S, which in turn interact with PS on apoptotic cells [25]. Similarly, MFG-E8 (lactadherin) forms a molecular bridge between PS and phagocyte integrins αvβ3 and αvβ5 [25]. The developmental endothelial locus-1 (DEL-1) also facilitates efferocytosis by binding both PS and αvβ3 integrin, with compartmentalized expression determining its anti-inflammatory versus pro-resolution functions [25].

Don't-Eat-Me Signals

Viable cells express surface molecules that actively inhibit phagocytic engulfment. The best-characterized "don't-eat-me" signal is CD47, which engages signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) on phagocytes to suppress engulfment [25]. During apoptosis, CD47 expression decreases, thereby removing this inhibitory signal [25]. Other don't-eat-me signals include CD31 (PECAM-1), which engages in homotypic interactions between viable cells and phagocytes to prevent inappropriate clearance [25].

Diagram 2: Molecular Recognition Systems in Efferocytosis. This diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways and molecular interactions between apoptotic cells and phagocytes during efferocytosis.

Intracellular Processing and Immunological Consequences

Following recognition and engulfment, the internalized apoptotic bodies undergo intracellular processing that shapes the subsequent immune response. The metabolic and signaling pathways activated during this process are critical for maintaining non-inflammatory clearance.

Engulfment and Phagolysosomal Degradation

The internalization of apoptotic bodies occurs through unique engulfment synapses that spatially organize recognition receptors and signaling components [25]. Unlike Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis, which typically produces pro-inflammatory responses, efferocytosis triggers distinct signaling cascades that promote immune tolerance. The internalized apoptotic material is trafficked through the endocytic pathway and ultimately degraded in phagolysosomes, with the resulting metabolic byproducts influencing macrophage function [25].

Immunometabolic Reprogramming

Efferocytosis induces significant metabolic reprogramming in phagocytes that supports their anti-inflammatory phenotype. The digestion of apoptotic cell-derived membranes delivers a substantial lipid load that promotes fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial respiration [25]. This metabolic shift away from glycolysis supports the production of anti-inflammatory mediators while limiting pro-inflammatory responses. Additionally, efferocytic macrophages upregulate enzymes such as 12/15-lipoxygenase that generate specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs) including resolvins, lipoxins, and maresins [25].

Anti-Inflammatory Mediator Production

The processing of apoptotic cells directly stimulates the production of immunosuppressive cytokines including TGF-β and IL-10 [25] [28]. These cytokines suppress the production of pro-inflammatory factors such as TNF, IL-1β, and IL-8, while promoting tissue repair and regeneration [25]. The strategic location of efferocytic receptors also contributes to immune silencing, as their engagement typically activates negative regulators of inflammatory signaling such as SOCS1 and SOCS3 [28].

Experimental Methods for Studying Apoptotic Cell Clearance

The investigation of efferocytosis requires specialized methodologies that can accurately quantify clearance efficiency and characterize the underlying molecular mechanisms. The following experimental approaches represent current best practices in the field.

In Vitro Co-culture Phagocytosis Assays

Live co-culture systems using fluorescently labeled apoptotic cells and macrophages enable real-time quantification of efferocytosis. The established protocol involves:

- Macrophage differentiation: THP-1 monocytes are differentiated into macrophages using 50 nM PMA (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate) for 48 hours [29]

- Apoptotic cell preparation: Target cells (e.g., prostate cancer PC3 or CL-1 cells) are engineered to express DsRed Express fluorescent protein or labeled with Cell Tracker Red CMTPX dye [29]

- Co-culture establishment: Fluorescent apoptotic cells are co-cultured with macrophages at optimized ratios (typically 1:10 to 1:20) in serum-free medium [29]

- Quantification: Phagocytosis is assessed using Confocal and Nomarski microscopy, with quantification of internalized fluorescent cells per macrophage [29]

This approach provides sensitive, measurable, and reproducible assessment of phagocytic activity that can be adapted for high-throughput screening of efferocytosis modulators.

Apoptosis Detection Methods

Different stages of apoptosis require specific detection strategies based on characteristic morphological and biochemical changes:

- Early apoptosis: Analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential using fluorescent cationic dyes (e.g., JC-1, TMRM) that exhibit potential-dependent accumulation in mitochondria [14]

- Mid-stage apoptosis: Annexin V staining for phosphatidylserine exposure combined with viability dyes (e.g., propidium iodide) to distinguish from necrotic cells [14] [28]

- Late apoptosis: DNA fragmentation detection via TUNEL assay or gel electrophoresis for nucleosomal ladder patterns [14]

- Morphological assessment: Electron microscopy for ultrastructural changes across all phases; light microscopy for Phase IIb apoptotic bodies [14]

Apoptotic Body Isolation and Characterization

The isolation and analysis of apoptotic bodies requires specialized techniques due to their heterogeneous size and composition:

- Differential centrifugation: Sequential centrifugation at increasing speeds (2,000 × g for 10 min followed by 10,000 × g for 30 min) to separate ABs from larger debris and smaller vesicles [27]

- Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS): Isolation of ABs based on specific surface markers (phosphatidylserine, caspase-3, calreticulin) and light scattering properties [27]

- Characterization methods: Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) for size distribution, cryo-electron microscopy for morphological assessment, and Western blotting for protein marker confirmation [27]

Table 3: Key Methodologies for Apoptotic Cell Clearance Research

| Experimental Goal | Recommended Methods | Key Readouts | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phagocytosis Quantification | Live co-culture with fluorescent targets, time-lapse imaging | Internalized targets per phagocyte, phagocytic index | Requires differential staining to distinguish attached vs. internalized targets |

| "Eat-Me" Signal Detection | Annexin V staining, antibody labeling for oxidized lipids | Surface PS exposure, oxidized epitope presentation | Must confirm apoptosis specificity with caspase inhibition |

| Phagocyte Recruitment | Transwell migration assays, microfluidic devices | Phagocyte migration toward apoptotic conditioned media | Distinguish chemotaxis from chemokinesis through checkerboard analysis |

| In Vivo Clearance Assessment | Intravital microscopy, labeled apoptotic cell injection | Clearance kinetics, phagocyte recruitment in tissue context | Consider anatomical differences in clearance efficiency |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table compiles critical reagents and their applications for investigating apoptotic cell clearance mechanisms, derived from current methodological approaches.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Apoptotic Clearance Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Mechanistic Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phagocyte Modulators | PMA (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate), Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor (PEDF) | Macrophage differentiation, phagocytosis enhancement | PKC activation, efferocytosis potentiation |

| Fluorescent Labels | DsRed Express, Cell Tracker Red CMTPX, Annexin V-FITC | Target cell labeling, PS exposure detection | Phagocytosis quantification, apoptosis staging |

| Receptor Blockers | Anti-TIM-4, anti-αvβ3 integrin, anti-CD36 antibodies | Pathway-specific inhibition | Mechanistic dissection of recognition systems |

| "Find-Me" Signal Receptors | P2Y2 agonists (ATP, UTP), G2A ligands (LPC) | Phagocyte recruitment studies | Chemotaxis assessment, signal transduction analysis |

| Metabolic Inhibitors | Fatty acid oxidation inhibitors, 12/15-LOX inhibitors | Immunometabolic studies | Resolution mediator production, metabolic reprogramming |

| Apoptosis Inducers | Staurosporine, actinomycin D, TNF-α/CHX | Controlled apoptosis induction | Standardized apoptotic cell preparation |

The non-inflammatory clearance of apoptotic bodies represents a sophisticated biological system that maintains tissue homeostasis while preventing inappropriate immune activation. The process integrates specific morphological changes during apoptosis with specialized recognition mechanisms and intracellular processing pathways that collectively ensure silent disposal of dying cells. Understanding these mechanisms provides not only fundamental biological insights but also therapeutic opportunities for manipulating efferocytosis in disease contexts ranging from chronic inflammation to autoimmunity. Continued technical innovation in tracking, quantifying, and modulating apoptotic cell clearance will further illuminate this critical biological process and its translational applications.

Detection and Analysis: Techniques for Visualizing Apoptotic Morphology

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is a fundamental process crucial for maintaining tissue homeostasis, organ development, and the elimination of damaged or mutant cells [14]. Its detection and accurate quantification are therefore paramount in both basic research and applied drug development. While numerous biochemical and molecular techniques exist, the morphological assessment of apoptosis remains a cornerstone, providing direct and often unequivocal evidence of cell death within its tissue context [30]. This technical guide focuses on the application of common light microscopy stains—Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), Giemsa, and Wright's—for identifying apoptotic cells, with its content rigorously framed within the classical morphological model that defines three phases of apoptosis: Phase I (cell shrinkage), Phase IIa (nuclear condensation), and Phase IIb (apoptotic body formation) [14].

The significance of morphology was cemented by Kerr, Wyllie, and Currie in 1972, who coined the term "apoptosis" to describe a specific morphological pattern of cell death distinct from necrosis [31] [30]. Despite the advent of sophisticated assays, guidelines advise that morphological characteristics are the definitive arbiter for diagnosing apoptosis, as biochemical features like DNA fragmentation can vary by cell type and lead to false negatives [30]. Light microscopy, with its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and capacity for providing storable specimens for further study, is an accessible and powerful tool for this purpose [14] [32]. This guide will detail how H&E, Giemsa, and Wright's staining can be deployed to detect the hallmark morphological features across the different phases of apoptosis, providing researchers and drug development professionals with clear methodologies and interpretive frameworks.

Morphological Hallmarks of Apoptosis Across Three Phases

The progression of apoptosis is characterized by a sequence of distinct structural changes. The following table summarizes the key features observable via light microscopy, correlated with the three morphological phases [14].

Table 1: Morphological Features of Apoptosis Across Key Phases

| Phase | Morphological Feature | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Phase I | Cell Shrinkage | Decreased cell volume, dense cytoplasm, loss of cell-cell contact [14] [30]. |

| Phase IIa | Chromatin Condensation | Nuclear chromatin condenses into dense masses (pyknosis) or marginalizes along the inner nuclear membrane [14]. |

| Phase IIb | Apoptotic Body Formation | The cell membrane buds off, forming small, membrane-bound vesicles containing cytoplasm and nuclear debris [14] [33]. |

These features form the basis for identifying apoptotic cells under the light microscope. It is important to note that cell shrinkage is one of the most ubiquitous characteristics, occurring in almost all instances of apoptosis regardless of the initiating stimulus [30]. Furthermore, the formation of apoptotic bodies is considered an important morphological marker, and their rapid phagocytosis by neighboring cells in vivo prevents inflammatory responses, making their detection in a small area challenging [14].

Staining Techniques and Their Applications

The choice of stain directly influences the ease and clarity with which these morphological features can be visualized. The following table provides a comparative overview of H&E, Giemsa, and Wright's staining for apoptosis detection.

Table 2: Comparison of Staining Methods for Apoptosis Detection by Light Microscopy

| Staining Method | Staining Principle | Key Apoptotic Features Visualized | Advantages & Disadvantages | Optimal Apoptosis Phase for Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H&E | Hematoxylin (basic) stains nucleic acids blue; Eosin (acidic) stains proteins pink [30]. | Cell shrinkage, cytoplasmic eosinophilia, nuclear pyknosis, and apoptotic bodies [14] [32]. | Advantages: Routine, widely available, provides good tissue context [32].Disadvantages: Chromatic differentiation can limit easy identification; may underestimate apoptosis [32]. | Phase IIb (apoptotic bodies) [14]. |

| Giemsa | Romanowsky-type stain; azure dyes and eosin differentiate cellular components. | Cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, and apoptotic body formation [34] [33]. | Advantages: Excellent for highlighting nuclear detail and morphology in cytospin preparations [30].Disadvantages: Requires consistent protocol for reproducible results. | Phase IIa and IIb [33]. |

| Wright's | Similar to Giemsa; a Romanowsky stain based on methylene blue and eosin. | Cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, and loss of surface microvilli [35] [33]. | Advantages: Standard in hematology; ideal for blood smears and suspended cells [35] [36].Disadvantages: Staining procedure requires preparation time and infrastructure [35]. | Phase IIa and IIb [33]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Stains

Protocol for Giemsa Staining [34] [33]

- Sample Preparation: Plate cells (e.g., PC-3 or CEM-SS leukemia cells) on a slide, for instance, via cytospin centrifugation.

- Fixation: Fix cells with 75% methanol for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Staining: Apply Giemsa working solution (diluted with phosphate buffer as per supplier's instructions) for the prescribed duration.

- Washing: Gently rinse the slide with distilled water to remove excess stain.

- Air-Drying: Allow the slide to air-dry completely.

- Observation: Examine under a light microscope using a 200x or higher magnification objective.

Protocol for H&E Staining [32] [30]

- Sample Preparation: Deparaffinize and rehydrate formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections through a graded alcohol series.

- Nuclear Staining: Immerse slides in Hematoxylin solution for a specified time (e.g., 5-10 minutes).

- Washing: Rinse in running tap water.

- Differentiation: Briefly dip in 1% acid alcohol (1% HCl in 70% ethanol).

- Bluing: Place in Scott's tap water or a weak ammonia solution.

- Cytoplasmic Staining: Counterstain with Eosin Y working solution (0.25-1%) for 1-5 minutes.

- Dehydration & Mounting: Dehydrate through graded alcohols, clear in xylene, and mount with a synthetic resin.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Morphological Apoptosis Detection

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application in Apoptosis Detection |

|---|---|

| Hematoxylin | A basic dye that binds to DNA/RNA, staining the nucleus blue-purple, allowing visualization of chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation [30]. |