Advanced SDS-PAGE Strategies for Resolving PARP-1 Fragments and Post-Translational Modifications

This methodological guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with optimized SDS-PAGE protocols for effective separation and analysis of PARP-1 fragments and their complex post-translational modifications.

Advanced SDS-PAGE Strategies for Resolving PARP-1 Fragments and Post-Translational Modifications

Abstract

This methodological guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with optimized SDS-PAGE protocols for effective separation and analysis of PARP-1 fragments and their complex post-translational modifications. Covering foundational principles of PARP-1 domain architecture and auto-modification, we detail specialized electrophoresis techniques for resolving serine ADP-ribosylation and other modifications. The article includes comprehensive troubleshooting for common artifacts, validation methods using mass spectrometry and Western blotting, and discusses implications for DNA repair research and PARP inhibitor development. These optimized protocols address the unique challenges posed by PARP-1's modification heterogeneity in studying DNA damage response mechanisms.

Understanding PARP-1 Domain Architecture and Modification Complexity

PARP-1 (Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1) is a critical nuclear enzyme that functions as a primary sensor of DNA damage, facilitating the cellular response to genotoxic stress. This multi-domain protein detects DNA strand breaks and catalyzes the synthesis of poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) chains onto target proteins, initiating DNA repair pathways and modulating chromatin structure. Understanding the structure-function relationships of PARP-1's domains is essential for research in DNA repair mechanisms and the development of targeted cancer therapies, particularly PARP inhibitors. The systematic analysis of these domains often relies on protein separation techniques, with SDS-PAGE serving as a fundamental method for resolving individual domains and proteolytic fragments to study their distinct functions and interactions.

Detailed Domain Structure and Function

PARP-1's functional versatility stems from its multi-domain architecture, where each domain contributes to DNA damage recognition, allosteric activation, and signal transduction. The table below summarizes the core structural and functional attributes of each domain.

Table 1: Core Domains of PARP-1 and Their Functions

| Domain | Location | Key Structural Features | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc Fingers (F1 & F2) | N-terminus | Zn²⁺-coordinating motifs [1] | Primary DNA break sensors; initiate multi-domain assembly [2] [1] |

| Zinc Finger (F3) | N-terminus | Structurally distinct from F1/F2 [1] | Contributes to DNA binding and inter-domain contacts [1] |

| BRCT Domain | Central Region | Protein-protein interaction fold [3] | Serves as an auto-modification site; mediates recruitment of repair proteins like XRCC1 [3] |

| WGR Domain | Central Region | Named for conserved Trp-Gly-Arg motif [2] | Propagates allosteric signal; bridges DNA-binding and catalytic domains [2] |

| Catalytic Domain (CAT) | C-terminus | Comprises Helical Domain (HD) & ART subdomain [2] | Catalyzes ADP-ribose polymerization from NAD⁺ [2] |

The following diagram illustrates the domain organization and the sequential activation mechanism of PARP-1.

Key Experimental Data and Reagents

The study of PARP-1 domains utilizes a suite of specialized reagents and mutants to dissect their individual and collective functions. The quantitative analysis of DNA binding affinity for various PARP-1 constructs provides critical insights into the allosteric regulation of its activity.

Table 2: DNA Binding Affinity of PARP-1 Constructs and Mutants Data derived from fluorescence polarization (FP) DNA binding assays [2]

| PARP-1 Construct | Description | K_D (nM) for DSB | K_D (nM) with EB-47 (Type I PARPi) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT (Full-length) | Wild-type PARP1 | 59.7 ± 9.2 | 8.4 ± 1.0 |

| ΔART | Catalytic ART subdomain deletion | 12.1 ± 4.6 | 15.4 ± 1.8 |

| L713F | Hyperactive mutant (Constitutive) | 21.3 ± 3.5 | 6.2 ± 3.1 |

| ΔV687-E688 | HD loop deletion mutant | 9.4 ± 1.3 | 8.0 ± 1.9 |

| WGR-CAT | WGR + Catalytic domains | >800 | 42.8 ± 5.7 |

| WGR-HD | WGR + Helical Domain | 7.0 ± 2.4 | Not Applicable |

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PARP-1 Domain Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Details / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant PARP1 Proteins | In vitro binding, activity, and structural assays | Human or murine PARP1, PARP2; full-length and domain fragments (e.g., Zn1-Zn3, WGR-CAT) [4] [2] |

| PARP Inhibitors (PARPi) | Probing allosteric mechanisms and catalytic function | EB-47 (Type I): Pro-retention, increases DNA affinity [2]. Niraparib: Shifts DNA to unkinked state [1] |

| DNA Substrates | Activating PARP-1 for functional studies | DSB, SSB, 1-nt gap, nucleosome core particle (NCP), cruciform, hairpin DNA [4] [5] [1] |

| HPF1 (Histone PARylation Factor) | Directs PARP1/PARP2 serine ADP-ribosylation | Essential for HPF1-dependent histone PARylation in DNA damage response [4] |

| Activity Assay Reagents | Measuring PARP-1 catalytic output | NAD⁺ (including ³²P-NAD⁺ for detection), PARG (hydrolyzes PAR chains) [4] |

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol: Analyzing PARP-1 Domain Assembly on DNA Damage by smFRET

Application: This protocol uses single-molecule Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (smFRET) to probe the conformational changes in DNA and the induced fit multi-domain assembly of PARP-1 upon binding to a single-strand break (SSB) [1]. This is crucial for understanding the initial steps of DNA damage recognition.

Workflow Overview: The experimental pathway for investigating PARP-1 domain assembly via smFRET is methodically outlined below.

Detailed Methodology:

DNA Substrate Preparation:

- Design a dumbbell-shaped DNA hairpin substrate containing a single-strand break (nick) between two double-stranded stems.

- Site-specifically label the 3' stem with a donor fluorophore (ATTO 550) and the 5' stem with an acceptor fluorophore (Alexa 647), positioned 18 bases apart for optimal FRET sensitivity [1].

smFRET Data Acquisition:

- Immobilize the labeled DNA construct on a passivated microscope surface for single-molecule imaging.

- Image the molecules using total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy.

- First, record the FRET efficiency baseline for the DNA substrate alone in the absence of protein. This typically shows a low-FRET state, indicating minimal DNA kinking [1].

Protein Titration and Complex Formation:

- Introduce the PARP-1 zinc finger 2 (F2) domain at saturation concentrations. Observe the FRET population shift to an intermediate FRET state, indicating F2-induced DNA kinking [1].

- Subsequently, titrate with the F1F2 double zinc finger fragment. This will shift the population to a high-FRET state, signifying substantial DNA kinking and the formation of inter-domain contacts between F1 and F2 [1].

- Finally, repeat the experiment with full-length PARP-1 to observe the final, fully assembled complex.

Data Analysis and Interpretation:

- Plot the populations of molecules in low, medium, and high FRET states under each condition (DNA only, +F2, +F1F2).

- Use computational modeling and structural ensemble calculations to convert the observed FRET efficiencies into DNA kinking angles [1].

- The sequential, protein-induced progression of DNA through increasingly kinked states provides direct evidence for an induced fit mechanism rather than conformational selection [1].

Protocol: Mapping PARP-1 Allostery and Auto-inhibition Using Mutant Analysis

Application: This protocol employs a series of PARP-1 point mutants and deletions to dissect the allosteric communication between the DNA-binding domains and the auto-inhibitory Helical Domain (HD), and to study the resulting functional consequences in cells [6] [2].

Key Mutants and Their Utility:

- Constitutively Active Mutant (L713F): This mutation within the HD destabilizes auto-inhibition, leading to high catalytic activity even in the absence of DNA damage. Reconstituting PARP-1 KO cells with L713F triggers apoptosis, which can be rescued by PARP inhibitors, demonstrating the toxic potential of unregulated PAR synthesis [6].

- ART Subdomain Deletion (ΔART): Removing the ART subdomain "frees" the HD, allowing it to fully engage with the WGR domain. This mimics the effect of Type I PARP inhibitors like EB-47, resulting in a ~5-fold increase in DNA binding affinity (Table 2). This construct is vital for crystallography studies aimed at capturing the active state of PARP1 [2].

- Mono-ADP-ribosylating Mutant (E988K): This catalytic domain mutation abolishes PAR synthesis capacity, restricting the enzyme to mono-ADP-ribosylation. When expressed in PARP-1 KO cells, it causes a DNA-damage-induced G2 arrest, revealing distinct cellular outcomes for mono- versus poly-ADP-ribosylation [6].

Methodology:

- Protein Purification: Express and purify wild-type and mutant PARP1 proteins (e.g., L713F, E988K, ΔART) using recombinant baculovirus or bacterial systems [6] [2].

- DNA Binding Assays: Determine the DNA binding affinity (K_D) of each mutant for double-strand breaks (DSBs) using fluorescence polarization (FP). Compare the values to wild-type PARP1 (Table 2) to quantify allosteric effects [2].

- Cellular Reconstitution: Stably express these mutants in PARP1 knockout HeLa or DT40 cells [6] [3]. This provides a clean background to study mutant-specific phenotypes without interference from the endogenous protein.

- Phenotypic Analysis:

- Assess PARP1 recruitment kinetics to laser-induced DNA damage sites using live-cell imaging.

- Measure cell viability and cell cycle progression following genotoxic stress.

- Analyze markers of apoptosis and DNA repair.

- Test the rescuing effects of PARP inhibitors on observed phenotypes [6].

The sophisticated multi-domain architecture of PARP-1, comprising zinc fingers, BRCT, WGR, and catalytic domains, enables its precise function as a DNA break sensor and signal transducer. The experimental strategies and protocols detailed herein—ranging from smFRET analysis of domain assembly to the cellular phenotyping of allosteric mutants—provide a robust framework for deconstructing this complex protein. Mastery of these techniques, underpinned by optimized SDS-PAGE separation for analyzing domains and cleavage products, is fundamental for advancing research in DNA repair biochemistry and for developing the next generation of PARP-targeted therapeutics.

Auto-modification Mechanisms and Their Impact on Electrophoretic Mobility

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) is a nuclear enzyme that functions as a critical DNA damage sensor. Its primary catalytic function involves the transfer of ADP-ribose units from NAD+ onto acceptor proteins, including itself—a process known as auto-modification or autoPARylation. This post-translational modification results in the attachment of either linear or branched chains of ADP-ribose (poly(ADP-ribose) or PAR) to target proteins [7]. PARP-1's ability to function simultaneously as both a catalytic enzyme and an acceptor substrate has created challenges in interpreting experimental data, particularly regarding the stoichiometry of PARP-1 molecules involved in auto-modification reactions and the direction of PAR chain growth [7].

The electrophoretic mobility of PARP-1 undergoes significant shifts during auto-modification due to the substantial addition of negatively charged ADP-ribose polymers. These mobility changes provide researchers with a valuable tool for monitoring PARP-1 activation and enzymatic activity. Understanding these auto-modification mechanisms is especially relevant in pharmaceutical development, as PARP inhibitors have emerged as promising cancer therapeutics that exploit synthetic lethality in DNA repair-deficient tumors [7] [8].

Molecular Mechanisms of PARP-1 Auto-modification

Domain Architecture and Catalytic Activation

PARP-1 is a 116-kDa protein comprising three primary functional domains: an N-terminal DNA-binding domain containing zinc fingers, a central auto-modification domain, and a C-terminal catalytic domain [9]. The auto-modification domain contains multiple glutamate, aspartate, and lysine residues that serve as acceptors for ADP-ribose units [9]. Upon binding to DNA damage sites through its zinc finger domains, PARP-1 undergoes a conformational change that relieves the auto-inhibitory configuration of its catalytic domain, enabling NAD+ substrate access and catalytic activity [10].

PAR Chain Initiation and Elongation

The auto-modification reaction occurs through a two-step process:

- Initiation: Transfer of the first ADP-ribose unit to specific acceptor amino acids (primarily glutamate, aspartate, or lysine residues) within PARP-1's auto-modification domain

- Elongation: Subsequent addition of ADP-ribose units to the initial monomer, forming linear or branched polymers [7]

Recent research has revealed that the histone PARylation factor 1 (HPF1) plays a crucial role in modulating PARP-1 activity. HPF1 forms a joint active site with PARP-1, influencing both the specificity of amino acid targeting (switching preference to serine residues) and the length of PAR chains synthesized [10]. HPF1 presence typically results in shorter PAR chains, affecting the electrophoretic mobility patterns observed in SDS-PAGE analysis.

Table 1: Key Proteins Regulating PARP-1 Auto-modification

| Protein/Enzyme | Function in PARP-1 Auto-modification | Effect on PAR Chain |

|---|---|---|

| PARP-1 | Catalyzes addition of ADP-ribose units to itself and other proteins | Forms linear/branched polymers |

| HPF1 | Forms joint active site with PARP-1 | Shortens PAR chain length, switches amino acid specificity to serine |

| PARG | Hydrolyzes PAR chains | Removes PAR modifications, reverses mobility shifts |

| PARP-2 | Partially redundant function with PARP-1 | Synthesizes shorter PAR chains than PARP-1 |

Experimental Protocols for Analyzing PARP-1 Auto-modification

In Vitro PARP-1 Auto-modification Assay

Purpose: To monitor PARP-1 auto-modification and its impact on electrophoretic mobility through SDS-PAGE analysis.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Purified PARP-1 protein (commercial sources or purified from overexpression systems)

- NAD+ solution (prepared fresh in appropriate buffer)

- Activated DNA or nucleosome core particles (for PARP-1 activation)

- PARP assay buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM DTT

- HPF1 protein (optional, for modulation studies)

- PARP inhibitors (e.g., Olaparib, AG-14361, UPF 1069) for inhibition controls

- SDS-PAGE equipment and materials

- Western blot transfer system

- Anti-PAR antibody (e.g., Trevigen 4336-BPC-100) or anti-PARP-1 antibody (e.g., Cell Signaling 9532S)

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup:

- Prepare 20 μL reactions containing 1-2 μg PARP-1 in PARP assay buffer

- Add activating DNA (200-500 ng) or nucleosome core particles

- Include experimental conditions: ± HPF1 (60-1000 nM), ± PARP inhibitors

- Pre-incubate for 5 minutes at 25°C

PARylation Initiation:

- Start reactions by adding NAD+ to final concentration of 50-500 μM

- Incubate at 25°C for 5-30 minutes

- Terminate reactions by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer and heating to 95°C for 5 minutes

Electrophoretic Analysis:

- Load samples on 6-10% SDS-PAGE gels (higher percentage for better resolution of modified PARP-1)

- Run electrophoresis at constant voltage until proper separation achieved

- Transfer proteins to PVDF membrane for Western blotting

- Probe with anti-PAR and anti-PARP-1 antibodies to visualize modified and total PARP-1

Troubleshooting Notes:

- High molecular weight smearing indicates extensive PARylation; optimize NAD+ concentration and reaction time

- Include PARG treatment controls to confirm PAR-specific modifications

- Use specialized buffers (e.g., Laemmli buffer without reducing agents) to preserve PAR chains

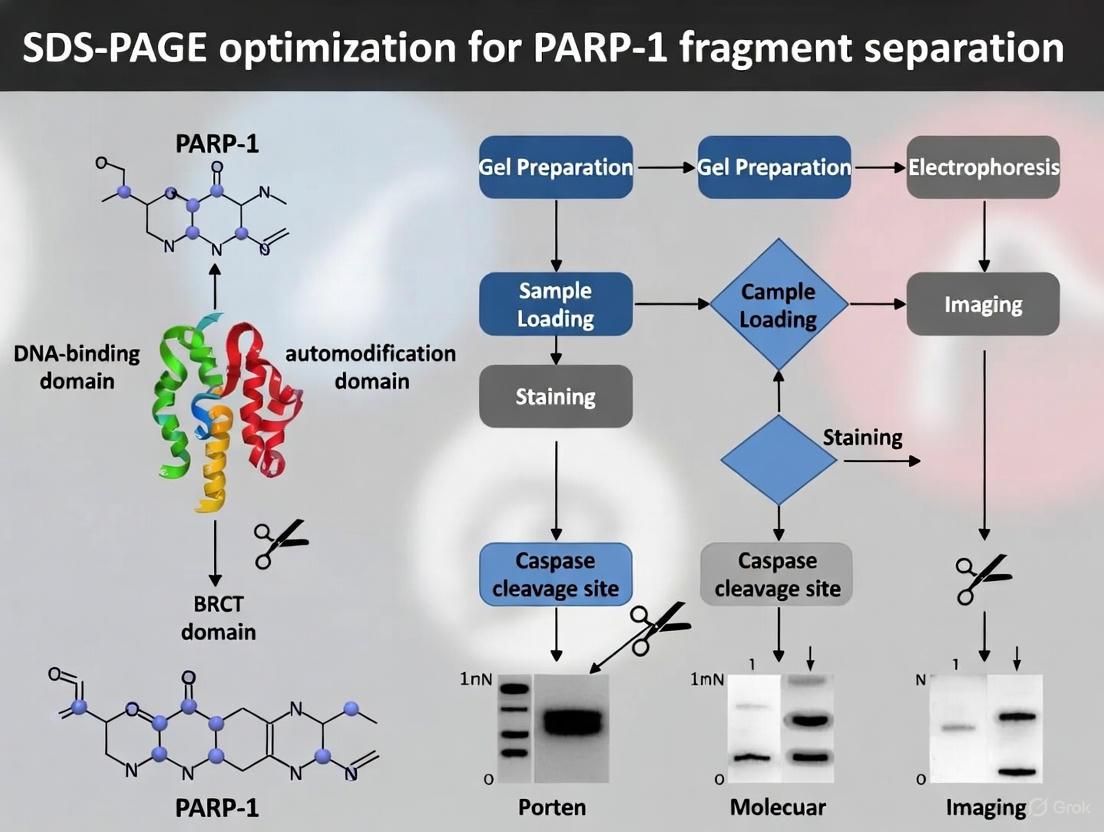

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for analyzing PARP-1 auto-modification and electrophoretic mobility shifts

Quantitative Assessment of Mobility Shifts

Data Analysis Method:

- Mobility Shift Quantification:

- Measure apparent molecular weights of PARP-1 bands

- Calculate shift magnitude relative to unmodified PARP-1

- Correlate shift extent with PAR chain length using molecular weight standards

- HPF1 Titration Experiments:

- Set up reactions with increasing HPF1 concentrations (0-2000 nM)

- Quantify PAR chain length using anti-PAR Western blotting

- Normalize data to PARP-1 total protein levels

Table 2: Effects of HPF1 on PARP-1 Auto-modification Parameters

| HPF1:PARP-1 Ratio | Auto-modification Level | PAR Chain Length | Electrophoretic Mobility |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0:1 | Baseline | Long polymers (≥20 units) | Pronounced smearing, high MW |

| 0.5:1 | Increased (2-3×) | Medium chains (10-15 units) | Defined bands with reduced smearing |

| 1:1 | Maximally stimulated (6× with NCP) | Short chains (5-10 units) | Tight band cluster, lower MW shift |

| 2:1 | Reduced from maximum | Very short chains (1-5 units) | Minimal shift,接近unmodified |

Impact of Auto-modification on Electrophoretic Mobility

Characteristic Mobility Patterns

Auto-modified PARP-1 exhibits distinctive electrophoretic mobility patterns that reflect the extent and nature of PAR modification:

Minimal Modification: Unmodified PARP-1 migrates as a ~116 kDa band with minimal smearing.

Moderate PARylation: Initial auto-modification produces a characteristic "ladder" or "smear" extending upward from the primary band, representing heterogeneous PAR chain lengths.

Extensive PARylation: Heavy modification results in pronounced high molecular weight smearing, often failing to enter standard SDS-PAGE separation gels due to enormous molecular weight increases and extreme negative charge.

HPF1-Modified Pattern: In the presence of HPF1, the heterogeneous smear is replaced by more defined bands with increased mobility, reflecting shorter PAR chains and more uniform modification [10].

Technical Considerations for SDS-PAGE Optimization

Gel System Optimization:

- Use low-percentage acrylamide gels (6-8%) for better resolution of high molecular weight PARylated species

- Implement gradient gels (4-20%) to capture broad molecular weight ranges

- Extend electrophoresis run times to improve separation of modified species

- Include high molecular weight markers (up to 500 kDa) for accurate size estimation

Sample Preparation Adjustments:

- Avoid excessive boiling which can degrade PAR chains

- Consider non-reducing conditions to preserve PAR structure

- Use specialized loading buffers without strong reducing agents

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PARP-1 Auto-modification Studies

| Reagent | Function/Application | Example Products/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| PARP-1 Protein | Primary enzyme for in vitro assays | Recombinant human PARP-1 (commercial vendors) |

| Activated DNA | PARP-1 activator for in vitro assays | DNase I-treated calf thymus DNA |

| Nucleosome Core Particles | Physiological activator | Recombinant or native NCPs |

| NAD+ | PARylation substrate | Sigma-Aldrich N1511, prepare fresh |

| HPF1 Protein | PARP-1 activity modulator | Recombinant human HPF1 |

| PARP Inhibitors | Activity controls, mechanistic studies | Olaparib, AG-14361, UPF 1069 |

| PARG | PAR chain degradation control | Recombinant PARG enzyme |

| Anti-PAR Antibodies | Detection of PARylation | Trevigen 4336-BPC-100, Millipore MABE1016 |

| Anti-PARP-1 Antibodies | Loading controls, total PARP-1 | Cell Signaling 9532S |

| PARG Inhibitors | PAR preservation | PDD 00017273 (Tocris 5952) |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

The analysis of PARP-1 auto-modification and its electrophoretic mobility patterns has significant applications in pharmaceutical research:

PARP Inhibitor Screening: Mobility shift assays provide a rapid method for evaluating inhibitor efficacy and mechanism of action.

Mechanistic Studies: Electrophoretic patterns can distinguish between different inhibition mechanisms (competitive vs. allosteric).

Biomarker Development: PARP-1 modification status in clinical samples may serve as a pharmacodynamic biomarker for PARP inhibitor efficacy.

Combination Therapy Development: Understanding auto-modification mechanisms aids in designing rational combination therapies with PARP inhibitors.

Figure 2: PARP-1 auto-modification pathway and regulatory mechanisms impacting electrophoretic mobility

The analysis of PARP-1 auto-modification through electrophoretic mobility shifts provides critical insights into PARP-1 enzymatic activity and regulation. The characteristic mobility patterns observed in SDS-PAGE—from discrete banding to heterogeneous smearing—directly reflect the extent of PAR modification and can be systematically quantified. The discovery of regulatory proteins like HPF1 has further refined our understanding of PAR chain length control and its manifestation in electrophoretic profiles. These methodologies continue to support drug discovery efforts, particularly in the development and characterization of PARP inhibitors as cancer therapeutics. Optimized SDS-PAGE protocols for PARP-1 fragment separation remain essential tools for researchers investigating DNA damage response mechanisms and developing targeted cancer therapies.

HPF1-dependent serine ADP-ribosylation versus glutamate/aspartate modifications

ADP-ribosylation is a reversible post-translational modification that regulates vital cellular processes, including DNA damage response. A pivotal advancement in this field has been the discovery that the DNA damage-dependent serine ADP-ribosylation (Ser-ADPr) is strictly governed by a cofactor, Histone PARylation Factor 1 (HPF1). In complex with PARP1 or PARP2, HPF1 remodels the enzyme's active site, shifting amino acid specificity from acidic residues (aspartate and glutamate) to serine residues. This application note details the key differences between these modification pathways and provides optimized methodologies for their investigation, framed within the context of optimizing SDS-PAGE for PARP-1 fragment separation research.

Biochemical Mechanisms and Specificity

The HPF1/PARP1 Complex and Active Site Remodeling

The specificity shift from aspartate/glutamate to serine ADP-ribosylation is mediated by HPF1 through structural remodeling of PARP1's catalytic domain. In the absence of HPF1, PARP1 preferentially modifies acidic residues (Asp/Glu) and undergoes automodification. HPF1 binding to the activated catalytic domain of PARP1 (which requires local unfolding of the autoinhibitory helical domain) creates a composite active site that enables serine modification [11].

Key residues in HPF1, including Phe268, Phe280, Asp283, Cys285, and Lys307, form an extensive interface with PARP1 that envelopes the active site region. Mutagenesis of these residues significantly disrupts HPF1/PARP1 binding and restores PARP1 hyper-automodification [11]. Particularly critical is HPF1 Arg239, which positions Glu284 for catalysis of serine ADP-ribosylation and helps neutralize negative charge in the active site [11].

Specificity and Mutual Exclusivity with Other Modifications

HPF1-dependent serine ADP-ribosylation exhibits complex interplay with other post-translational modifications, particularly on histone tails. Research demonstrates that acetylation of H3K9 is mutually exclusive with ADP-ribosylation of the adjacent H3S10 residue both in vitro and in vivo [12]. This crosstalk represents a dynamic addition to the complex network of modifications that shape the histone code and influences DNA damage response signaling.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of HPF1-Dependent Serine vs. Aspartate/Glutamate ADP-ribosylation

| Characteristic | Serine ADP-ribosylation | Aspartate/Glutamate ADP-ribosylation |

|---|---|---|

| Dependency | Strictly HPF1-dependent [13] | HPF1-independent; PARP1 alone [14] |

| Chemical Bond | O-glycosidic linkage [14] | Ester linkage [14] |

| Chemical Stability | Highly stable; resistant to acidic conditions [14] | Labile; sensitive to heat, pH changes, and DNA shearing [14] |

| Temporal Dynamics in DNA Damage | Sustained signal; more enduring [14] | Initial wave; transient signal [14] |

| Primary Enzymes | PARP1/HPF1 and PARP2/HPF1 complexes [13] | PARP1 alone; other PARP family members [15] |

| Cellular Reversal | ARH3 hydrolase [14] | PARG hydrolase (new finding) [14] |

| Histone Modification Interplay | Mutually exclusive with proximal acetylation (e.g., H3K9ac vs. H3S10ADPr) [12] | Not well characterized |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Considerations

Preservation of Labile Ester-Linked Modifications

Traditional sample preparation methods involving heat and extreme pH systematically undermine detection of aspartate/glutamate ADP-ribosylation due to the lability of ester bonds. The following optimized protocol enables reliable preservation and detection of these modifications:

Cell Lysis and Denaturation:

- Lyse cells directly with 4% SDS lysis buffer at room temperature (20-25°C)

- Avoid boiling samples as even brief heating rapidly hydrolyzes ester-linked ADPr

- Include PARP inhibitors in lysis buffer to prevent post-lysis ART activity

- Process samples immediately after lysis without freezing-thawing cycles

Electrophoresis and Immunoblotting:

- Maintain samples at room temperature throughout SDS-PAGE preparation

- Use pre-cast gels to minimize gel polymerization time

- Transfer proteins using standard western blot protocols

- Detect using broad-specificity mono-ADPr antibodies (e.g., AbD43647) [14]

Proteomic Sample Preparation:

- Perform protein digestion at 37°C for short durations (2-4 hours)

- Use acidic digestion conditions with Arg-C Ultra protease

- Avoid prolonged incubation and alkaline conditions

- Process samples immediately for LC-MS/MS analysis [14]

In Vitro Reconstitution of Serine ADP-ribosylation

To biochemically characterize HPF1-dependent serine modification, the following reconstitution system can be employed:

Reaction Components:

- Purified PARP1 (or PARP2) protein: 100-200 nM

- HPF1 protein: 200-400 nM (maintain 1:2-1:1 ratio with PARP1)

- Histone substrate (nucleosomes, core histones, or H3 peptides): 1-2 μg

- Activating DNA (ssDNA or gapped DNA): 100-200 ng

- NAD+ substrate: 10-100 μM (including 32P-NAD+ for radioactive detection)

- Reaction buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl₂

Reaction Conditions:

- Assemble reactions on ice without NAD+

- Initiate by adding NAD+ and incubate at 30°C for 10-30 minutes

- Terminate with SDS sample buffer (without boiling)

- Analyze by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography or immunoblotting [13]

Controls:

- Omit HPF1 to demonstrate dependency

- Include PARP inhibitor (olaparib, 1-10 μM) to confirm PARP specificity

- Use serine-to-alanine mutant substrates (e.g., H3S10A) to verify modification sites [13]

Signaling Pathways and Dynamics

The differential regulation and dynamics of serine versus aspartate/glutamate ADP-ribosylation create a sophisticated temporal signaling system in DNA damage response.

Diagram 1: Signaling pathways for HPF1-dependent serine and HPF1-independent aspartate/glutamate ADP-ribosylation in DNA damage response. The two pathways represent distinct temporal and regulatory mechanisms with different biological outcomes.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Investigating ADP-ribosylation Pathways

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| PARP Inhibitors | Olaparib, Talazoparib, Rucaparib, Veliparib [16] | Inhibit PARP catalytic activity; research tools and clinical applications |

| HPF1 Mutants | HPF1 F268S, D283H, R239A [11] | Disrupt HPF1/PARP1 binding; study HPF1-dependent functions |

| Specific Antibodies | Site-specific Ser-ADPr antibodies; Broad mono-ADPr AbD43647 [14] [17] | Detect specific ADPr modifications; immunoblotting and immunofluorescence |

| Hydrolase Tools | Recombinant PARG, ARH3 [14] | Reverse specific ADPr types; study modification dynamics |

| Activity Assays | 32P-NAD+ incorporation, ETD mass spectrometry [13] | Detect and map ADP-ribosylation sites |

| Cell Models | HPF1 KO cells, PARP1 KO cells [13] [14] | Study pathway dependencies and biological functions |

Technical Considerations for SDS-PAGE Optimization

When optimizing SDS-PAGE for PARP-1 fragment separation in ADP-ribosylation studies, several critical factors must be considered:

Sample Preparation:

- For analyzing aspartate/glutamate modifications: avoid heat denaturation and maintain samples at 4°C to room temperature

- For serine modifications: standard boiling (95°C, 5 minutes) is acceptable due to thermal stability

- Include PARG and ARH3 inhibitors in lysis buffers to preserve modifications during processing

Gel System Selection:

- Use 4-12% or 4-20% gradient gels for optimal separation of PARP1 fragments (25-120 kDa range)

- Consider Tris-acetate gels for better separation of higher molecular weight PARP1 species

- Include molecular weight markers spanning 25-250 kDa for accurate size determination

Detection and Analysis:

- Implement simultaneous immunoblotting with modification-specific and total protein antibodies

- Use fluorescent secondary antibodies for quantitative comparison across samples

- Account for potential gel shifts due to ADP-ribosylation modifications

This methodological framework enables researchers to effectively distinguish between these biochemically distinct modification pathways and investigate their respective functions in DNA damage response and other cellular processes.

DNA Damage-Induced PARP-1 Structural Changes and Detection Challenges

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) serves as a primary sensor for DNA single-strand breaks (SSBs) in eukaryotic cells, initiating a critical signaling cascade for DNA damage repair. This nuclear enzyme detects DNA lesions and catalyzes the transfer of ADP-ribose units from nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) to target proteins, including itself—a process known as poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation (PARylation) [18] [19]. PARP-1 is exceptionally abundant, with approximately one molecule per 1,000 base pairs of DNA, and its enzymatic activity can increase up to 500-fold upon DNA damage recognition [19]. Understanding the structural transitions PARP-1 undergoes during damage detection and the subsequent technical challenges in analyzing these changes is fundamental to advancing research in DNA repair mechanisms and developing targeted cancer therapies, particularly PARP inhibitors.

Structural Domains and DNA Damage Sensing Mechanism

Domain Organization of PARP-1

PARP-1 possesses a modular architecture consisting of six structured domains that coordinate its damage sensing and signaling functions. The N-terminal region contains three zinc-binding domains: two zinc fingers (F1 and F2) that directly recognize DNA damage, followed by a third zinc finger (Zn3) or zinc ribbon domain that contributes to DNA-dependent activation [20] [21]. The central region includes a BRCT domain containing auto-modification sites and a WGR domain that participates in multi-domain assembly. The C-terminal region houses the catalytic domain, comprising a helical subdomain (HD) and the ADP-ribosyl transferase (ART) subdomain that executes PAR synthesis [20]. In the absence of DNA, these domains behave as largely independent units in an extended "beads-on-a-string" conformation [20] [21].

Table 1: PARP-1 Structural Domains and Their Functions

| Domain | Position | Primary Function | DNA Binding Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc Finger 1 (F1) | 1-209 | Primary DNA damage recognition | Binds 5' side of DNA breaks |

| Zinc Finger 2 (F2) | 1-209 | Primary DNA damage recognition | Binds 3' side of DNA breaks |

| Zinc Finger 3 (Zn3) | 233-273 | Allosteric regulation | Necessary for DNA-stimulated activation |

| BRCT | 384-486 | Auto-modification sites | Protein-protein interactions |

| WGR | 540-656 | Multi-domain assembly | Contributes to DNA-dependent activation |

| Catalytic (HD+ART) | 784-1014 | PAR synthesis | Allosterically inhibited until DNA binding |

DNA Damage Recognition and Structural Transition

PARP-1 employs an induced fit mechanism for DNA damage recognition rather than conformational selection [20]. Single-molecule FRET studies reveal that PARP-1 binding converts DNA containing single-strand breaks from a largely unperturbed conformation through an intermediate state to a highly kinked DNA conformation. The F2 domain initiates this process by binding the 3' side of the break and inducing initial DNA bending, followed by F1 binding to the 5' side, which further kinks the DNA approximately 90° [20]. This sequential binding triggers a comprehensive multi-domain assembly cascade where the zinc fingers, WGR domain, and catalytic domain coalesce into a compact, enzymatically active structure at the damage site [22] [20]. This allosteric transition releases auto-inhibition of the catalytic domain, activating PARP-1 for PAR synthesis.

Detection Challenges and Technical Considerations

Dynamic Structural Transitions

The highly dynamic nature of PARP-1 presents significant challenges for structural analysis. Solution studies using small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) demonstrate that the N-terminal DNA-binding region (residues 1-486) exists as an extended, flexible arrangement of domains in the absence of DNA, with a radius of gyration (Rg) of approximately 46-48Å and a maximum dimension (Dmax) of 150Å [21]. Upon DNA binding, PARP-1 undergoes substantial compaction, particularly in the zinc ribbon domain region. These rapid conformational changes, coupled with the transient nature of PARP-1-DNA interactions, complicate traditional structural biology approaches and require real-time monitoring techniques such as single-molecule FRET.

PARylation Heterogeneity and Turnover

The PARylation reaction itself introduces analytical complications due to its heterogeneity and rapid turnover. PAR chains can reach 200 units in length with both linear and branched structures [19]. This heterogeneity, combined with the low abundance of PARylated species and the labile nature of the modification, creates significant challenges for mass spectrometry-based analyses [19]. Furthermore, the half-life of PAR chains is exceptionally short (<1 minute) due to efficient degradation by poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (PARG) and other hydrolases [19]. This rapid turnover necessitates careful experimental timing and often requires PARG inhibition to capture PARylation events.

Complex Formation and Phase Separation

Recent research has revealed that PARP-1 undergoes liquid-liquid phase separation at DNA damage sites, forming co-condensates with damaged DNA through a process involving PARP1 dimerization and multimerization along DNA filaments [22]. These condensates exert mechanical forces that maintain synapsis of broken DNA ends and create enzymatically active compartments for PAR synthesis. The compositional complexity and dynamic nature of these structures present unique challenges for biochemical isolation and characterization, particularly in distinguishing between specific binding and phase partitioning.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Structural Analysis Techniques

Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) SAXS provides low-resolution structural information for PARP-1 and its complexes in solution. The experimental workflow involves:

- Purifying recombinant PARP-1 fragments (e.g., hparp486, residues 1-486) to homogeneity

- Concentrating protein to 3-9 mg/ml in appropriate buffer (e.g., 20mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl)

- Collecting scattering data at multiple concentrations to assess concentration dependence

- Processing data using Guinier analysis to determine radius of gyration (Rg)

- Calculating distance distribution functions and ab initio shape reconstructions

- Fitting known domain structures into the overall envelope [21]

Single-Molecule FRET (smFRET) smFRET enables real-time observation of PARP-1-induced DNA bending and conformational changes:

- Designing DNA dumbbell substrates with a single-strand break between two hairpins

- Labeling with fluorophores (ATTO 550 on 3' stem, Alexa647 on 5' stem) positioned 18 bases apart

- Immobilizing DNA molecules on quartz slides via biotin-neutravidin linkage

- Acquiring time-resolved fluorescence data with total internal reflection microscopy

- Calculating FRET efficiency distributions for DNA alone and with PARP-1 domains

- Determining DNA kinking angles through computational modeling [20]

PARP-1 Activity and PARylation Assays

Automodification Assays

- Incubating purified PARP-1 with activated DNA (nick, gap, or blunt end) and NAD+ in reaction buffer

- Stopping reactions at timed intervals with PARP inhibitor or SDS sample buffer

- Separating PARylated species by SDS-PAGE with special considerations:

- Using low-acrylamide concentrations (6-8%) for better resolution of high molecular weight PARylated forms

- Including protein molecular weight markers exceeding 250 kDa

- Implementing modified electrophoresis conditions (extended run times, cooled apparatus)

- Detecting PAR modifications via immunoblotting with PAR-specific antibodies

- Quantifying automodification extent by comparing PARP-1 mobility shifts [18] [23]

PARP-1 DNA Binding Assays Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays (EMSAs):

- Preparing fluorescently labeled DNA substrates containing specific lesions (nicks, gaps, ends)

- Incubating DNA with purified PARP-1 domains or full-length protein

- Separating protein-DNA complexes from free DNA using non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels

- Visualizing complexes with fluorescence imaging or autoradiography

- Quantifying binding affinity through concentration-dependent experiments [21]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for PARP-1 Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PARP Inhibitors | Olaparib, Niraparib, PJ34 | Mechanistic studies, therapeutic applications | Different classes affect DNA binding differently (pro-retention vs. pro-release) [20] |

| DNA Substrates | Nicked DNA, gapped DNA, blunt ends, 3'-overhangs | DNA binding and activation assays | Different structures activate PARP-1 to varying degrees [21] |

| PAR Detection Reagents | PAR-specific antibodies, PBZ domains | PARylation detection and quantification | Specificity varies for different PAR chain lengths and structures |

| Hydrolase Inhibitors | PARG inhibitors, ARH3 inhibitors | PAR stabilization for detection | Essential for capturing transient PARylation events [19] |

| Tagged PARP-1 Constructs | GFP-PARP1, FLAG-PARP1, truncated domains | Localization and interaction studies | Truncations help isolate specific functional domains [24] |

| Interaction Partners | XRCC1, HPF1, Histones | Pathway mapping and functional assays | HPF1 switches PARP-1 amino acid specificity to serine [25] |

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow

PARP-1 Activation Pathway and Experimental Approaches

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Addressing PARP-1 Auto-modification

Recent studies utilizing separation-of-function PARP-1 mutants have revealed that auto-modification plays distinct roles in different cellular processes. An auto-modification-deficient PARP-1 mutant (serine to alanine substitution at four key sites) retains catalytic activity but demonstrates impaired release from DNA damage sites, leading to replication fork slowing and defects in Okazaki fragment processing [23]. This mutant provides a valuable tool for distinguishing between PARP-1's scaffolding and enzymatic functions. When studying PARP-1 auto-modification, researchers should consider:

- Utilizing auto-modification-deficient mutants as controls

- Monitoring replication fork dynamics in addition to repair recruitment

- Assessing Okazaki fragment maturation in auto-modification contexts

- Examining potential synthetic lethality with FEN1 inhibition [23]

Analyzing Composite Post-Translational Modifications

The discovery of serine ADP-ribosylation as a target for ester-linked ubiquitylation creates new analytical challenges and opportunities [25]. This composite modification requires specialized proteomic approaches:

- Implementing short, acidic ArgC digestion to preserve acid-labile linkages

- Developing enrichment strategies using specialized reader domains (e.g., ZUD domain of RNF114)

- Employing specific chemical elution (zinc chelation) to maintain modification integrity

- Creating modular detection reagents through protein ligation technologies (e.g., SpyTag) [25]

Phase Separation Studies

Investigating PARP-1-DNA co-condensates requires specialized methodologies:

- Bottom-up reconstitution of functional DNA repair sites using purified components

- Single-molecule imaging to monitor condensate dynamics

- Atomic force microscopy for structural characterization

- Assessing mechanical properties through biophysical approaches [22]

Concluding Remarks

The structural plasticity of PARP-1 during DNA damage recognition represents both a fascinating biological mechanism and a significant technical challenge. Successfully analyzing these dynamic transitions requires integrated methodological approaches that account for PARP-1's modular architecture, rapid conformational changes, and complex post-translational modifications. The continued development of separation techniques, including optimized SDS-PAGE protocols, coupled with advanced structural and single-molecule methods, will be essential for elucidating the full scope of PARP-1 functions in genome maintenance and for developing next-generation PARP-targeted therapies.

Recent Advances in PARP-1 Biology from 2024-2025 Research

Application Note 1: The Role of PARP1 Auto-modification in DNA Replication

Recent research has unveiled critical functions of PARP1 auto-modification (AM) beyond its well-established role in DNA repair. A 2025 study identified a specific separation-of-function PARP1 mutant, deficient in auto-modification but retaining catalytic activity, revealing its essential role in controlling replication fork speed and ensuring faithful Okazaki fragment maturation [23]. This discovery provides a new mechanistic understanding of replication stress and offers novel perspectives for therapeutic strategies.

Key Quantitative Findings

Table 1: Key Functional Parameters of Auto-modification-Deficient PARP1

| Parameter | Auto-modification Deficient PARP1 | Wild-type PARP1 |

|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Activity | Retained | Retained |

| Eviction from DNA Breaks | Impaired (timely release lost) | Normal |

| Replication Fork Speed | Increased | Normally controlled |

| Replication Stress | Increased formation | Prevented |

| Okazaki Fragment Processing | Impaired (synthetic lethality with FEN1 inhibition) | Normal [23] |

Biological Significance and Research Context

The auto-modification-deficient PARP1 mutant was generated by mutating four specific serine residues. Proteomic analyses using this mutant have mapped the extensive ADP-ribosylation network present at the replication fork [23]. The study demonstrates that auto-modification is dispensable for initial repair factor recruitment. Its primary function is to facilitate the timely release of PARP1 from DNA break sites. When this release is impaired, the trapped PARP1 obstructs the access of other essential replication and repair factors to the DNA, creating a blockage that leads to replication stress [23]. This is particularly critical during Okazaki fragment processing on the lagging strand. The finding of synthetic lethality between the loss of PARP1 auto-modification and inhibition of the flap endonuclease FEN1 directly implicates PARP1's auto-modification state in this fundamental process [23].

Implications for SDS-PAGE Optimization in PARP-1 Research

These findings highlight the necessity of optimizing SDS-PAGE protocols to separate and identify distinct PARP1 fragments and proteoforms. The auto-modified and unmodified states of PARP1, as well as caspase-cleaved fragments during apoptosis, exhibit different molecular weights and charges, influencing their migration. Precise separation is crucial for:

- Accurately determining the auto-modification status of PARP1 in cellular models.

- Evaluating the efficacy of PARP inhibitors that function by trapping PARP1 on DNA.

- Investigating the cleavage of PARP1 during different cell death pathways (e.g., apoptosis, parthanatos) in neurodegenerative disease models [26].

Diagram 1: PARP1 auto-modification controls DNA replication.

Application Note 2: PARP1 in Transcription-Replication Conflicts and Neurodegeneration

A landmark 2024 study revealed a novel mechanism for PARP inhibitor (PARPi) synthetic lethality, shifting the paradigm from the dominant "PARP trapping" model. The research established that PARP1, in conjunction with the TIMELESS-TIPIN complex, plays a crucial role in shielding DNA replication forks from transcription-replication conflicts (TRCs) during early S phase [27]. Furthermore, PARP1 overactivation is increasingly implicated in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases through mechanisms like parthanatos [26].

Key Insights and Data

Table 2: PARP1 in Cellular Stress and Disease Contexts

| Context | PARP1 Function / Effect | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|

| TRCs (Early S Phase) | Protects replisome from conflicts with transcription machinery. | PARPi induces γH2AX/53BP1/RAD51 foci; suppressed by transcription inhibitor DRB [27]. |

| Synthetic Lethality (HR Deficiency) | Prevents toxic DNA damage from TRCs. | siRNA PARP1 depletion is synthetic lethal with HR deficiency; damage from TRCs, not trapped PARPs, is key [27]. |

| Neurodegeneration | Overactivation depletes NAD+/ATP, triggering parthanatos. | PARP1 overactivation causes neuronal death via AIF translocation; inhibition is therapeutic [26]. |

| Okazaki Fragment Processing | Processes unligated Okazaki fragments during replication. | Unligated Okazaki fragments are a major source of S-phase PARP activity [28]. |

Research Implications

The discovery that PARP1 protects against TRCs suggests that the cytotoxic effect of PARP inhibitors in HR-deficient cells stems primarily from an accumulation of unresolved conflicts during early S phase, rather than solely from the physical blockage of replication forks by trapped PARP1 [27]. This refined understanding has significant implications for cancer therapy. In parallel, research into neurodegenerative diseases highlights the "dark side" of PARP1 activity. Severe DNA damage can lead to hyperactivation of PARP1, causing catastrophic depletion of cellular NAD+ and ATP pools, which ultimately triggers a novel form of programmed cell death known as parthanatos [26].

Protocol 1: Live-Cell Imaging for PARP1 Dynamics at DNA Damage Sites

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 methodology paper, details how to quantitatively measure PARP1 kinetics at micro-irradiation-induced DNA damage sites, a key assay for studying PARP trapping and inhibitor effects [29].

I. Generation of Stable Cell Lines (2-3 weeks)

- Objective: Create HeLa Kyoto (or other) cell lines expressing fluorescently tagged PARP1 at near-physiological levels using Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC) transgenes.

- Procedure:

- BAC DNA Purification: Purify transfection-grade BAC DNA using a NucleoBond PC 100 Midi kit or equivalent. CRITICAL: Do not freeze BAC DNA; store at 4°C for ≤1 month. Avoid vortexing; gently mix by tapping tubes to prevent DNA fragmentation [29].

- Cell Transfection: Transfect cells using Effectene Transfection Reagent per manufacturer's instructions (e.g., 400 ng DNA per 35 mm glass-bottom dish) [29].

- Selection & Validation: Select positive clones with appropriate antibiotics for >1 week after control cell death. Validate by confirming recruitment of the fluorescent PARP1 to laser-induced DNA damage sites via microscopy [29].

II. Live-Cell Imaging and Micro-Irradiation

- Objective: Capture high-quality kinetics of PARP1-EGFP at DNA damage sites with high temporal resolution.

- Procedure:

- Culture Cells: Maintain stable cells in FluoroBrite DMEM supplemented with GlutaMAX and serum during imaging [29].

- Micro-Irradiation: Use a confocal microscope equipped with a precise UV laser system to induce DNA damage in a small, defined nuclear region. CRITICAL: Avoid pre-treatment with DNA damage-sensitizing agents to preserve native cellular responses [29].

- Image Acquisition: Acquire images at high speed (sub-second intervals) using spinning-disk confocal imaging to minimize photobleaching and phototoxicity [29].

III. Image Analysis and Kinetic Modeling

- Objective: Extract robust, quantitative parameters from imaging data.

- Procedure:

- Analysis: Use automated image analysis software (e.g., CellTool) to generate high-quality kinetic data of fluorescence intensity at damage sites over time [29].

- Modeling: Apply mathematical models to the fluorescence recovery curves to extract meaningful biochemical parameters, such as binding and release rates, rather than relying on qualitative assessment [29].

Diagram 2: Workflow for PARP1 dynamics analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PARP1 Biology Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Auto-modification Deficient PARP1 Mutant | Separates auto-modification function from DNA binding/catalysis. | Defining the specific role of auto-PARylation in replication fork speed and Okazaki fragment processing [23]. |

| BAC Transgenes for PARP1-EGFP | Enables expression of fluorescently tagged PARP1 at near-physiological levels. | High-quality live-cell imaging of PARP1 recruitment and dynamics without overexpression artifacts [29]. |

| Next-Gen PARP1-Selective Inhibitors | Inhibits PARP1 with reduced activity against PARP2. | Improving therapeutic safety profiles and probing distinct biological functions of PARP1 vs. PARP2 [28]. |

| HPF1 Protein | Forms joint active site with PARP1/2 for serine ADP-ribosylation. | In vitro studies of histone PARylation and chromatin remodeling in response to genotoxic stress [4]. |

| PARG and ARH3 Enzymes | Hydrolyzes PAR chains (dePARylation). | Studying the turnover of PAR modifications and its role in neurodegeneration and DNA repair [26]. |

Protocol 2: In Vitro Analysis of PARP1 Activity in a Nucleosome Context

This protocol is based on a 2025 study that detailed methods for analyzing PARP1 and PARP2 activities on nucleosome core particles (NCPs), which is crucial for understanding PARP function in a chromatin context [4].

I. Preparation of Nucleosome Core Particles (NCPs)

- Objective: Assemble defined NCPs containing site-specific DNA lesions.

- Procedure:

- Histone Preparation: Isolate core histones (H2A, H2B, H3, H4) from a suitable source, such as chicken erythrocytes, and purify via chromatography. Verify homogeneity by SDS-PAGE [4].

- DNA Template Synthesis: Generate DNA constructs containing the Widom 601 nucleosome positioning sequence via PCR from a plasmid template (e.g., pGEM-3z/603). Introduce a one-nucleotide gap (simulating a BER intermediate) at a specific superhelical location (SHL) [4].

- NCP Reconstitution: Mix purified histones and DNA template in high-salt buffer and dialyze into low-salt buffer to promote spontaneous NCP assembly [4].

II. PARP Activity Assay on NCPs

- Objective: Measure the efficiency and pattern of PARP auto-modification and histone heteromodification.

- Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Incubate PARP1 (or PARP2) with assembled NCPs in reaction buffer. Include HPF1 to study serine-directed ADP-ribosylation. Supplement with NAD+,-

- Reaction Setup (continued): Supplement with NAD+, including [²²P]-NAD+ for detection [4].

- Reaction Termination: Stop the reaction at various time points by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer.

- Analysis: Resolve proteins by SDS-PAGE. Visualize PARP1 automodification and histone PARylation using autoradiography (for [²²P]) or immunoblotting with PAR-specific antibodies. The shift in PARP1 mobility on the gel indicates the extent of auto-modification [4].

III. Data Interpretation

- The architecture of the NCP and the precise location of the DNA lesion significantly impact the efficiency and pattern of histone ADP-ribosylation, with PARP2 showing greater sensitivity to these structural features than PARP1 [4]. Optimized SDS-PAGE is critical here to resolve the heterogeneous, high-molecular-weight ADP-ribosylated species.

Optimized SDS-PAGE Protocols for PARP-1 Fragment Resolution

Sample Preparation Strategies for Preserving PARP-1 Modifications

PARP-1 is a crucial nuclear enzyme involved in DNA damage response, functioning as a primary sensor of DNA single-strand breaks [20]. Its activity leads to various post-translational modifications (PTMs), including auto-ADP-ribosylation, which regulates its function in DNA repair pathways [30] [23]. However, studying these modifications presents significant technical challenges due to the chemical lability of certain ADP-ribosylation linkages, particularly ester-linked aspartate/glutamate modifications that are highly susceptible to degradation under standard sample preparation conditions [14]. This application note details optimized protocols for preserving PARP-1 modifications during sample preparation, specifically tailored for SDS-PAGE-based separation in research contexts.

The Challenge of PARP-1 Modification Lability

PARP-1 catalyzes the transfer of ADP-ribose units from NAD+ to target proteins, forming different chemical linkages with varying stability [30]. The O-glycosidic serine ADP-ribosylation (Ser-ADPr) demonstrates relatively high chemical stability, remaining intact even under highly acidic conditions (44% formic acid at 37°C) [14]. In contrast, ester-linked aspartate/glutamate ADP-ribosylation (Asp/Glu-ADPr) is exceptionally labile, with significant losses occurring during standard sample preparation methods that involve heating or extreme pH conditions [14].

This lability has created systematic detection gaps in PARP-1 research, potentially leading to incomplete understanding of PARP-1 signaling dynamics. Recent investigations reveal that Asp/Glu-ADPr represents an initial wave of PARP-1 signaling, contrasting with the more enduring nature of serine mono-ADP-ribosylation [14]. Therefore, implementing preservation-focused methodologies is essential for comprehensive analysis of PARP-1 biology.

Optimized Sample Preparation Protocols

Protocol 1: Preservation of Ester-Linked ADP-Ribosylation for Immunoblotting

This protocol maximizes recovery of labile ester-linked PARP-1 modifications through temperature-controlled lysis and denaturation procedures [14].

Materials

- Lysis buffer: 4% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)

- Protease inhibitors

- PARP inhibitors (optional, for basal state analysis)

- Benzonase nuclease (optional, for reducing viscosity)

- Precast SDS-PAGE gels

- Transfer apparatus and membranes

- Anti-mono-ADPr antibodies (e.g., AbD43647)

Procedure

Cell Lysis:

- Aspirate culture medium and wash cells with ice-cold PBS.

- Add 4% SDS lysis buffer directly to cells (100-200 μL for a 6-well plate).

- Maintain samples at room temperature throughout lysis procedure.

- Scrape cells and transfer lysates to microcentrifuge tubes.

- Critical: Do not boil samples at any stage.

DNA Shearing:

- Pass lysates through a 25-gauge needle 10-15 times to reduce viscosity.

- Alternatively, add Benzonase nuclease (1000 U) and incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes.

Protein Quantification:

- Determine protein concentration using compatible assays (e.g., BCA assay).

- Adjust concentrations using lysis buffer.

SDS-PAGE Preparation:

- Mix normalized protein lysates with non-reducing sample buffer.

- Omit heating step or maintain at room temperature for ≤10 minutes if minimal heating is unavoidable.

- Load samples onto precast SDS-PAGE gels.

Electrophoresis and Transfer:

- Run gels at constant voltage (100-150V) using standard SDS-PAGE conditions.

- Transfer proteins to PVDF or nitrocellulose membranes.

- Proceed with standard immunoblotting protocols using anti-ADPr antibodies.

Protocol 2: Acidic Digestion for Mass Spectrometry Analysis

This protocol enables proteomic mapping of ester-linked ADP-ribosylation sites through optimized digestion conditions that minimize hydrolysis [14].

Materials

- Lysis buffer: 4% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)

- Arg-C Ultra protease or trypsin

- Digestion buffer: 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 6.0-6.5)

- C18 desalting columns

- HILIC enrichment materials

- Mass spectrometry-compatible solvents

Procedure

Protein Extraction and Denaturation:

- Lyse cells as described in Protocol 1 (room temperature procedure).

- Add 10 mM DTT and incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes.

- Add 20 mM iodoacetamide and incubate in dark at room temperature for 20 minutes.

Protein Digestion:

- Dilute SDS concentration to <0.5% using digestion buffer.

- Add Arg-C Ultra protease (1:50 enzyme-to-substrate ratio).

- Digest at 37°C for 4-6 hours (shorter duration than typical protocols).

- Maintain acidic pH conditions (pH 6.0-6.5) throughout digestion.

Peptide Cleanup:

- Acidify samples with trifluoroacetic acid (0.5% final concentration).

- Desalt using C18 columns according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Lyophilize and store at -80°C until analysis.

Enrichment of Modified Peptides:

- Resuspend peptides in HILIC loading buffer.

- Perform HILIC enrichment using standard protocols.

- Elute modified peptides for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Comparative Analysis of Methodologies

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Sample Preparation Methods for PARP-1 Modification Preservation

| Parameter | Standard Protocol | Optimized Preservation Protocol | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heating Step | 95°C for 5-10 minutes [31] [32] | Room temperature or ≤37°C | Eliminates heat-induced hydrolysis |

| Lysis Conditions | Boiling in 1× LDS buffer [31] | 4% SDS at room temperature [14] | Preserves ester linkages |

| Asp/Glu-ADPr Detection | Minimal to undetectable [14] | Strong signal enhancement [14] | >5-fold improvement |

| Digestion Time | 12-16 hours (overnight) | 4-6 hours [14] | Reduces exposure to hydrolysis |

| Optimal pH Range | pH 7.5-8.5 | pH 6.0-6.5 for digestion [14] | Minimizes base-catalyzed hydrolysis |

Table 2: Chemical Stability of PARP-1-Mediated ADP-Ribosylation Linkages

| Modification Type | Chemical Bond | Stability to Heat | Stability to Acid | Stability to Base | Recommended Preservation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serine ADPr | O-glycosidic | High (stable at 95°C) [14] | High (stable in 44% formic acid) [14] | Moderate | Standard protocols sufficient |

| Glutamate ADPr | Ester linkage | Low (significant loss at 70°C+) [14] | Low | Very low | Room temperature lysis essential |

| Aspartate ADPr | Ester linkage | Low (significant loss at 70°C+) [14] | Low | Very low | Room temperature lysis essential |

| Lysine ADPr | N-glycosidic | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Mild conditions recommended |

Visualizing PARP-1 Modification Workflows

Sample Preparation Decision Pathway for PARP-1 Modification Analysis

PARP-1 Modification Stability Profiles and Preservation Strategies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for PARP-1 Modification Studies

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-mono-ADPr Antibodies (AbD43647) | Detection of various mono-ADPr types | Works for Ser, Asp, and Glu ADPr; requires preservation protocols for ester-linked forms | [14] |

| 5-Et-6-a-NAD+ | Orthogonal NAD+ analog for specific PARP targeting | Used with engineered KA-PARP variants; enables specific target identification | [33] |

| Arg-C Ultra Protease | Acid-stable protease for MS sample prep | Maintains activity at pH 6.0; enables shorter digestion times | [14] |

| HILIC Enrichment Materials | Enrichment of methylated/ADP-ribosylated peptides | Suitable for large-scale identification of modified peptides | [9] |

| PARP Inhibitors (Niraparib, EB47) | Modulating PARP-1 DNA binding | Different classes affect PARP-1 dynamics differently; useful for mechanistic studies | [20] |

| Benzonase Nuclease | Reduces sample viscosity | Degrades nucleic acids without affecting protein modifications | [14] |

Technical Considerations for SDS-PAGE Optimization

When implementing these preservation strategies within SDS-PAGE workflows, several technical adjustments are necessary:

Electrophoresis Conditions: Standard SDS-PAGE running conditions (50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.7) remain appropriate after sample preparation using preservation protocols [34] [31].

Sample Buffer Modifications: Consider preparing samples with non-reducing buffer when analyzing intact PARP-1 complexes. If disulfide bond reduction is necessary, use lower temperatures (37°C instead of 95°C) and shorter incubation times.

Transfer Efficiency: Labile modifications may require optimized transfer conditions. Wet transfer systems at 4°C typically provide better recovery than semi-dry systems for ester-linked ADPr.

Validation Controls: Always include parallel samples processed using standard (heat-containing) protocols to confirm the enhancement of ester-linked modification detection.

The strategic implementation of modification-preserving sample preparation methods enables comprehensive analysis of PARP-1 biology that was previously inaccessible through standard protocols. By maintaining room temperature lysis, avoiding extreme pH conditions, and implementing shorter processing times, researchers can successfully stabilize labile ester-linked ADP-ribosylation modifications for downstream SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry applications. These methodologies provide essential tools for advancing our understanding of PARP-1 signaling dynamics in DNA damage response and facilitating drug development efforts targeting PARP-1 activity.

Gel Percentage Optimization for Different PARP-1 Fragment Sizes

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) is a critical nuclear enzyme involved in DNA damage repair and the maintenance of genomic integrity. Research into PARP1 function frequently requires the clear separation and identification of its full-length and proteolytic fragments using SDS-PAGE. The generation of PARP1 fragments occurs through two primary mechanisms: caspase-mediated cleavage during apoptosis and regulated proteolysis. During apoptosis, executioner caspases (caspase-3 and -7) cleave full-length PARP1 (113-116 kDa) into characteristic 24-kDa and 89-kDa fragments [35]. The 24-kDa fragment contains the DNA-binding domain and irreversibly binds to DNA breaks, while the 89-kDa fragment, which contains the catalytic domain, is translocated from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and directly induces caspase-mediated DNA fragmentation [35]. Additionally, research has identified other regulatory fragments and modifications, including auto-modification deficient mutants and various ADP-ribosylation states that can affect apparent molecular weight [23].

Optimizing SDS-PAGE conditions is therefore essential for accurately resolving these fragments, particularly when studying apoptotic progression, DNA damage response, or the efficacy of PARP inhibitors in cancer research and drug development.

SDS-PAGE Optimization Guidelines

Recommended Gel Percentages for PARP-1 Fragments

Based on the molecular weights of PARP1 and its primary fragments, the following gel percentages are recommended for optimal resolution:

Table 1: Optimal SDS-PAGE Conditions for PARP-1 Fragment Separation

| Target Protein/Fragment | Molecular Weight (kDa) | Recommended Gel Percentage | Key Resolvable Fragments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full-length PARP1 | 113 - 116 | 7.5% | Resolves full-length from major degradation products |

| PARP1 Large Fragment | 89 | 10% | Separates 89-kDa from full-length (116-kDa) |

| PARP1 Small Fragment | 24 | 15% | Resolves 24-kDa fragment from other small proteins |

| Comprehensive Analysis | 24 - 116 | 4-20% Gradient | Resolves entire fragment range on a single gel |

Rationale for Gel Percentage Selection

The recommended gel percentages are calculated based on the optimal separation range of polyacrylamide gels. A 7.5% gel is ideal for resolving high molecular weight proteins around 100-150 kDa, making it suitable for analyzing full-length PARP1. A 10% gel provides superior resolution for proteins between 50-100 kDa, enabling clear distinction between the 89-kDa fragment and the full-length protein. For the small 24-kDa fragment, a 15% gel is necessary for adequate resolution in the lower molecular weight range. For experiments where all fragments must be visualized simultaneously, a 4-20% gradient gel provides the broadest linear separation range.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Detecting PARP1 Cleavage During Apoptosis

This protocol is adapted from methods used to study RSL3-induced ferroptosis-apoptosis crosstalk, where PARP1 cleavage serves as a key apoptotic marker [35].

Reagents and Solutions:

- Cell Lysis Buffer: RIPA buffer supplemented with 1x protease inhibitor cocktail and 1 mM PMSF.

- Running Buffer: 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.3.

- Transfer Buffer: 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 20% methanol.

- Primary Antibodies: Anti-PARP1 antibody (specific for both full-length and cleaved fragments).

- Secondary Antibodies: HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Treat cells with apoptotic inducers (e.g., RSL3 for ferroptosis-apoptosis crosstalk) [35].

- Harvest cells and lyse in RIPA buffer on ice for 30 minutes.

- Centrifuge lysates at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- Collect supernatant and determine protein concentration using a BCA assay.

- Prepare samples with 2x Laemmli buffer, denature at 95°C for 5 minutes.

Gel Electrophoresis:

- Load 20-40 μg of total protein per well on a 4-20% gradient gel or the appropriate percentage gel from Table 1.

- Run gel at 100 V constant voltage until the dye front reaches the bottom (approximately 90 minutes).

Western Blotting:

- Transfer proteins to PVDF membrane at 100 V for 60 minutes in transfer buffer with ice pack.

- Block membrane with 5% non-fat milk in TBST for 1 hour.

- Incubate with primary antibody (diluted according to manufacturer's recommendation) overnight at 4°C.

- Wash membrane 3 times with TBST, 10 minutes each.

- Incubate with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Develop with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate and image.

Expected Results: Successful apoptosis induction will show both the full-length PARP1 (116 kDa) and the cleaved 89-kDa fragment. In late apoptosis, the 24-kDa fragment may also be detectable using a higher percentage gel.

Protocol 2: Monitoring PARP1 Auto-modification

This protocol is designed to detect PARP1 auto-modification, which can alter its electrophoretic mobility, as studied in auto-modification deficient PARP1 mutants [23].

Special Considerations:

- PARP1 auto-modification through ADP-ribosylation can cause a noticeable gel shift, appearing as a smear or higher molecular weight bands.

- To confirm the nature of the modification, include treatments with PARG (poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase) to remove PAR chains [4].

Procedure:

- Induction of DNA Damage:

- Treat cells with DNA-damaging agents (e.g., H₂O₂ for oxidative stress) to activate PARP1.

- For inhibition studies, pre-treat with PARP inhibitors (e.g., Olaparib, Rucaparib) for 1-2 hours before damage induction.

Sample Preparation and Electrophoresis:

- Prepare lysates as described in Protocol 1.

- Use a 7.5% gel to better resolve the higher molecular weight modified species.

- Include controls: untreated, DNA-damaged, and DNA-damaged with PARP inhibitor.

Detection:

- Transfer and immunoblot as in Protocol 1.

- Use antibodies specific for PARP1 and/or poly(ADP-ribose) to confirm modification.

Expected Results: Auto-modified PARP1 will appear as a smear above the main 116-kDa band. This smear should be reduced or eliminated in samples treated with PARP inhibitors or PARG.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for PARP-1 Fragment Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| PARP Inhibitors | Olaparib, Rucaparib, Niraparib, Talazoparib [36] | Inhibit PARP1 catalytic activity; study synthetic lethality in BRCA-deficient cells. |

| Apoptosis Inducers | RSL3 [35] | Induce caspase-dependent PARP1 cleavage during ferroptosis-apoptosis crosstalk. |

| DNA Damage Agents | H₂O₂ (oxidative stress) [25] | Activate PARP1 and induce auto-modification. |

| PROTAC Degraders | 180055 (Rucaparib-based) [36] | Specifically degrade PARP1 protein without DNA trapping effect. |

| PARP Activity Assays | BRET reporter assay [37] | Quantify PARP1 influence on DNA repair pathway choice (NHEJ, MMEJ, HR). |

| Hydrolases | PARG, ARH3 [25] | Remove poly(ADP-ribose) chains or serine ADP-ribosylation to confirm modification. |

PARP1 Signaling and Experimental Workflow

The following diagrams illustrate the key signaling pathways involving PARP1 cleavage and the experimental workflow for gel-based analysis.

PARP1 Cleavage in Apoptosis: This pathway shows how apoptotic stimuli trigger PARP1 cleavage into distinct fragments that promote cell death.

PARP1 Fragment Analysis Workflow: This chart outlines the key steps from cell treatment to fragment detection and analysis.

Technical Considerations and Troubleshooting

- Gel Choice Validation: Always include pre-stained molecular weight markers to verify separation efficiency. For critical applications, validate gel performance with control lysates containing known PARP1 fragments.

- Mobility Shift Interpretation: PARP1 auto-ADP-ribosylation can cause a characteristic smearing pattern above the main band [23]. This should not be confused with non-specific degradation, which typically appears as multiple discrete lower molecular weight bands.

- Antibody Selection: Ensure antibodies recognize both full-length and cleaved PARP1. Some antibodies are specific to the N-terminal (detecting full-length and 24-kDa fragment) or C-terminal (detecting full-length and 89-kDa fragment) regions.

- Advanced Applications: For studying PARP1 in DNA repair compartmentalization, consider that PARP1 forms co-condensates with DNA at damage sites [22], which may affect its extraction efficiency and apparent molecular weight.

Electrophoresis Conditions for Resolving Modification Heterogeneity

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) is a critical nuclear enzyme that functions as a primary sensor of DNA damage [20]. Upon detecting DNA strand breaks, PARP-1 becomes activated and catalyzes the transfer of ADP-ribose units from NAD+ to various acceptor proteins, including itself—a process known as auto-poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation [4] [21]. This post-translational modification generates a complex heterogeneity of protein-ADP-ribose conjugates that range from mono-ADP-ribosylation to extensive poly(ADP-ribose) chains of varying lengths [25]. Resolving this modification heterogeneity presents significant analytical challenges, as these modifications dramatically alter the molecular weight, charge, and conformation of PARP-1 and its fragments. SDS-PAGE electrophoresis remains the foundational method for separating and analyzing these complex modification patterns, providing critical insights into PARP-1 function in DNA repair, chromatin remodeling, and the mechanisms of PARP inhibitor therapies [38] [39].

Key PARP-1 Modifications and Their Impact on Electrophoretic Mobility

Types of PARP-1 Modifications

Table 1: PARP-1 Modifications and Their Electrophoretic Behavior

| Modification Type | Modified Residues | Key Enzymes/Cofactors | Impact on SDS-PAGE Mobility | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serine mono-ADP-ribosylation | Serine residues | PARP1/HPF1 complex [25] | Discrete band shifts | Anti-ADPr-specific antibodies [25] |

| Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation | Aspartate, Glutamate, Serine [25] | PARP1 catalytic domain | High molecular weight smears | Anti-PAR antibodies [38] |

| Ubiquitination | Lysine (K418 site) [38] | USP10 (deubiquitinase) | Discrete band shifts | Anti-ubiquitin antibodies [38] |

| Auto-modification | Multiple sites in BRCT domain [21] | PARP1 catalytic domain | Multiple discrete bands | Coomassie, silver stain |

Consequences of Modification Heterogeneity

The extensive modification of PARP-1 creates several analytical challenges for electrophoresis-based separation. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation generates highly negatively charged polymers that can result in characteristic smearing patterns on SDS-PAGE gels due to the heterogeneous chain lengths and branching patterns [21]. In contrast, mono-ADP-ribosylation and ubiquitylation typically produce more discrete band shifts, enabling clearer interpretation of specific modification states [38] [25]. The coexistence of multiple modification types on a single PARP-1 molecule further complicates the electrophoretic profile, requiring optimized separation conditions to resolve these complex patterns. Understanding these modification-specific electrophoretic behaviors is essential for accurate interpretation of PARP-1 function and activation status in response to DNA damage.

Experimental Protocols for PARP-1 Fragment Analysis

Protein Purification and Homogeneity Verification

Protocol: Recombinant PARP1 Purification and Quality Control

- Expression System: Recombinant human PARP1 is expressed in E. coli and purified using affinity chromatography followed by gel filtration [21].

- Homogeneity Verification: Verify protein homogeneity by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis followed by Coomassie Blue or silver staining. Purified PARP1 should show >95% purity as assessed by densitometric analysis of stained gels [21].

- Concentration Determination: Determine protein concentration using spectrophotometric methods (absorbance at 280 nm) with correction for turbidity if necessary.

- Aliquoting and Storage: Aliquot purified proteins to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles and store at -80°C in appropriate storage buffers containing glycerol and protease inhibitors.

Quality Control Note: The purity and integrity of the starting PARP1 material is critical for obtaining interpretable results in modification studies. Always include a reference sample of unmodified PARP1 on every gel for comparison with modified samples.

Electrophoresis Conditions for PARP-1 Modification Analysis

Protocol: SDS-PAGE Separation of PARP-1 and Its Fragments

- Gel System: Discontinuous SDS-PAGE system using Tris-glycine buffers

- Gel Composition:

- Resolving Gel: 8-12% acrylamide (depending on fragment size range)

- Stacking Gel: 4% acrylamide

- Sample Preparation:

- Dilute protein samples in 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer (125 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 0.02% bromophenol blue)

- Add β-mercaptoethanol (final concentration 5%) or DTT (final concentration 100 mM) as reducing agent

- Heat samples at 95°C for 5 minutes to denature proteins

- Electrophoresis Conditions:

- Running Buffer: 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.3

- Run at constant voltage: 80 V through stacking gel, 120 V through resolving gel

- Continue electrophoresis until dye front reaches bottom of gel

- Molecular Weight Standards: Include prestained protein molecular weight markers covering relevant size range (approximately 20-130 kDa for PARP-1 fragments)

Critical Considerations: For optimal resolution of PARP-1 modification heterogeneity, use longer gel formats (10-15 cm resolving gel) and lower acrylamide concentrations (8%) for better separation of high molecular weight modified species. The high negative charge of poly(ADP-ribose) chains can affect SDS binding and migration behavior, which should be considered when interpreting results.

Detection of PARP-1 Modifications