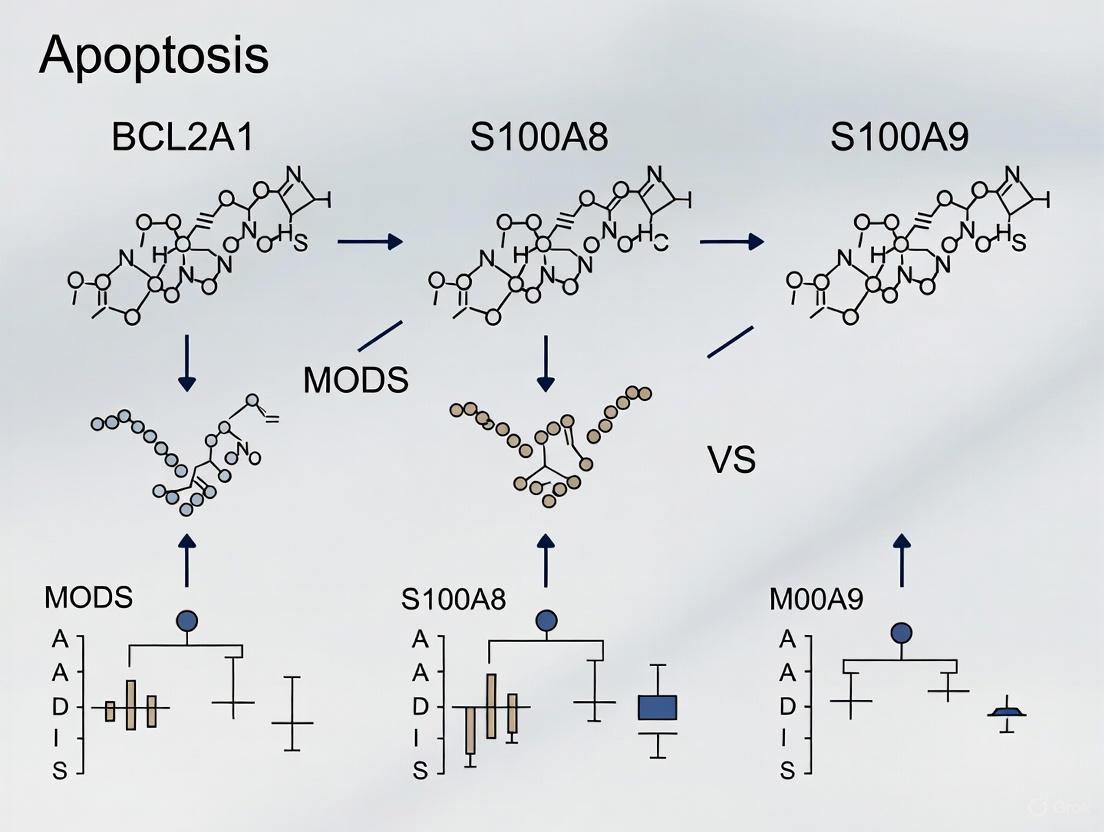

BCL2A1, S100A8, and S100A9 Expression in MODS: Unraveling Apoptosis and Inflammation Biomarkers for Therapeutic Insights

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of BCL2A1, S100A8, and S100A9 expression in Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS) compared to controls, targeting researchers and drug development professionals.

BCL2A1, S100A8, and S100A9 Expression in MODS: Unraveling Apoptosis and Inflammation Biomarkers for Therapeutic Insights

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of BCL2A1, S100A8, and S100A9 expression in Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS) compared to controls, targeting researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational roles of these genes in apoptosis and inflammation, outlines robust methodological approaches for expression profiling, addresses common troubleshooting challenges, and validates findings through comparative analyses to ensure clinical relevance and reliability in biomarker discovery.

Foundational Insights: BCL2A1, S100A8, and S100A9 in MODS Pathophysiology and Mechanisms

Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS) is a life-threatening clinical condition characterized by the progressive and potentially reversible physiological dysfunction of two or more organ systems following an acute insult such as sepsis, trauma, or other critical illnesses [1]. This syndrome represents a significant challenge in intensive care settings worldwide, with mortality rates escalating with the number of organs affected, ranging from approximately 30% with two failing organs to 50-70% when three to four organs are impaired [2] [3].

Clinical Context and Pathophysiology

MODS exists on a clinical continuum with incremental degrees of organ dysfunction rather than representing a single event [1]. It can be categorized as primary MODS, which results directly from a well-defined insult where organ dysfunction occurs early, or secondary MODS, which develops as a consequence of a maladaptive host response and is identified within the context of systemic inflammation [1].

The pathogenesis of MODS involves a complex interplay of inflammatory mediators. Following an initial insult, there is often a release of pro-inflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukins (IL-1, IL-6, IL-8), and other mediators that create a state of "immunologic dissonance" [1]. This leads to widespread endothelial damage, microvascular thrombosis, and impaired tissue oxygenation. The syndrome affects multiple organ systems:

- Circulatory system: Characterized by significant derangements in autoregulation, vasodilation, increased microvascular permeability, and reversible myocardial depression [1]

- Pulmonary system: Endothelial injury leads to disturbed capillary blood flow and enhanced permeability, resulting in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [1]

- Gastrointestinal system: Barrier function may be compromised, allowing bacterial translocation that can propagate systemic inflammation [1]

Global Burden and Epidemiology

MODS represents a substantial global health burden, particularly in intensive care units. A 2022 study conducted in Iranian ICUs found a MODS prevalence of 56.2% among critically ill patients, with an average MODS score of 6.87 ± 1.59 [3]. The study identified several clinical variables significantly associated with MODS, including duration of hospitalization and ICU stay, number of involved organs, Glasgow Coma Scale scores, and various severity scoring systems [3].

Sepsis remains a primary catalyst for MODS development. Globally, sepsis affects approximately 48.9 million people annually, with about 11 million deaths attributed to this condition [4]. The burden intensifies in ICU settings, where sepsis prevalence reaches approximately 31% with associated mortality rates ranging from 30% to 46%, depending on geographic region and available resources [4]. Among patients with trauma-induced sepsis, approximately 26.95% develop MODS, with 28-day mortality rates significantly higher in MODS patients (23.82%) compared to non-MODS patients (11.21%) [5].

Key Biomarkers in MODS Pathogenesis

Recent research has identified several key biomarkers implicated in MODS pathogenesis, particularly those related to apoptotic pathways:

S100A8/S100A9 and BCL2A1 in MODS

Emerging evidence highlights the significance of three key genes in MODS pathophysiology: S100A8, S100A9, and BCL2A1 [2].

S100A8 and S100A9 are calcium-binding proteins that form a stable heterodimer (calprotectin) constitutively expressed in neutrophils and monocytes [6] [7]. These proteins function as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) that amplify inflammatory responses through interaction with pattern recognition receptors like Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) [6] [7]. During inflammation, S100A8/A9 is actively released and modulates inflammatory responses by stimulating leukocyte recruitment and inducing cytokine secretion [6].

BCL2A1 is a member of the BCL-2 protein family that regulates apoptotic processes. As an anti-apoptotic protein, BCL2A1 promotes cell survival by inhibiting pro-apoptotic signals [2].

All three genes demonstrate significantly elevated expression in MODS patients compared to controls and collectively participate in the "oxidative phosphorylation" signaling pathway [2]. Their coordinated overexpression suggests a potentially critical role in the dysregulated immune response and organ dysfunction characteristic of MODS.

MODS Scoring and Assessment

Several scoring systems have been developed to quantify organ dysfunction and predict outcomes in MODS patients:

Table 1: MODS Scoring Systems and Clinical Utility

| Scoring System | Components Assessed | Score Range | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score (MODS) [3] | Six key components (respiratory, renal, hepatic, cardiovascular, hematological, neurological) | 0-24 (higher scores indicate greater dysfunction) | Predicts ICU mortality risk; assesses degree of multi-organ dysfunction |

| Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) [1] | Six organ systems (coagulation, pulmonary, cardiovascular, liver, central nervous, renal) | 0-4 per organ system (higher scores indicate worse function) | Tracks organ dysfunction/failure over time; ≥2 points indicates organ dysfunction |

| Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II [3] | 12 physiological variables, age, chronic health | 0-71 (higher scores indicate greater severity) | Estimates mortality risk in critically ill patients |

These scoring systems enable clinicians to stratify patients by risk, monitor disease progression, and evaluate response to interventions. The MODS score specifically calculates mortality risk based on the degree of multi-organ dysfunction, with higher scores correlating with increased mortality risk [3].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Predictive Model Development for MODS

Recent research has employed advanced statistical and machine learning approaches to develop predictive models for MODS. A 2025 retrospective cohort study utilizing the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV (MIMIC-IV) database developed several predictive models for MODS in trauma-induced sepsis patients [5]. The methodology included:

- Patient Selection: Identification of trauma patients with sepsis within the first day of ICU admission, excluding those with prior ICU admissions, stays <1 day, or meeting MODS criteria on ICU day 1 [5]

- Feature Selection: Application of the Boruta algorithm (an all-relevant feature selection method based on random forests) to identify key predictors from 42 candidate variables [5]

- Model Development: Construction of a nomogram using logistic regression and implementation of various machine learning models including K-nearest neighbor, support vector classifier, random forest, extreme gradient boosting, and multilayer perceptron [5]

- Model Validation: Temporal validation using data from 2017-2019, with performance evaluation based on discrimination, calibration, and decision curve analysis [5]

This study identified several key predictors of MODS, including Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II) scores, use of mechanical ventilation, and vasopressor administration [5]. In validation, all models significantly outperformed traditional scoring systems, with the random forest model demonstrating the highest performance (AUC: 0.769, 95% CI: 0.712-0.826) [5].

Biomarker Identification Workflow

The identification and validation of key apoptosis-related genes in MODS followed a comprehensive bioinformatics approach [2]:

Biomarker Identification Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for MODS Biomarker Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Datasets | GEO Datasets: GSE66099, GSE26440, GSE144406 [2] | Training and validation sets for biomarker discovery and model development |

| Apoptosis-Related Gene Panels | 802 non-duplicate ARGs including S100A9, S100A8, BCL2A1 [2] | Candidate gene selection for focused analysis of apoptotic mechanisms in MODS |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA), Cytoscape software [2] | Identification of gene modules most correlated with MODS and network visualization |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Multiple algorithms combined with expression verification [2] | Screening and validation of key genes with predictive value for MODS |

| Clinical Validation Assays | Expression verification in clinical samples [2] | Confirmation of key gene expression differences between MODS patients and controls |

Signaling Pathways in MODS Pathogenesis

The pathophysiology of MODS involves complex interactions between inflammatory and apoptotic pathways:

MODS Signaling Pathways

Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome continues to represent a significant challenge in critical care medicine, with substantial global burden and devastating clinical consequences. The emergence of biomarkers such as S100A8, S100A9, and BCL2A1 provides promising avenues for improved early detection, risk stratification, and targeted therapeutic interventions. Ongoing research integrating multi-omics approaches, machine learning algorithms, and well-validated clinical prediction models holds promise for advancing our understanding and management of this complex syndrome. As our knowledge of MODS pathophysiology deepens, particularly regarding the interplay between inflammatory and apoptotic pathways, opportunities for developing more effective, personalized treatment strategies continue to expand.

The B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) protein family constitutes a critical checkpoint in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, regulating mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) and the subsequent release of cytochrome c [8] [9]. This family is divided into pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic members, which interact to determine cellular survival. BCL2A1 (also known as Bfl-1 or BCL2-related gene expressed in fetal liver) is an anti-apoptotic member of this family, first identified as an early-response gene induced by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [8]. While all anti-apoptotic proteins (including BCL2, BCL-XL, MCL1, BCL-w, and BCL-B) share four BCL2 homology (BH) domains and function to sequester pro-apoptotic proteins, BCL2A1 remains one of the less extensively studied members of the family [8] [10]. Its expression is highly regulated by nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), and it exerts important pro-survival functions, particularly in the hematopoietic system [8]. This overview details the structure, function, and regulation of BCL2A1, with a specific focus on its emerging role in critical illness, particularly multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), and its interplay with inflammatory proteins S100A8 and S100A9.

BCL2A1 Gene Structure, Protein Domains, and Interaction Partners

Genomic Organization and Structural Features

The human BCL2A1 gene is located on chromosome 15q24.3 and contains three exons [8]. The most common transcript utilizes exons 1 and 3, producing a 175-amino acid protein. A notable structural characteristic of BCL2A1 is its lack of a well-defined C-terminal transmembrane domain, which is present in other anti-apoptotic BCL2 family members and typically aids in anchoring to the outer mitochondrial membrane [8] [10]. Despite this, BCL2A1 is found localized at the mitochondria in healthy cells, and its C-terminus is crucial for both its anti-apoptotic function and subcellular localization [8] [9]. The protein consists of nine α-helices and displays the characteristic hydrophobic groove, formed by the BH1, BH2, and BH3 domains, that is common to all anti-apoptotic BCL2 proteins and serves as the main site for interactions with pro-apoptotic partners [8].

An alternative splice variant, Bfl-1S, incorporates all three exons. A premature stop codon in exon 3 results in a 163-amino acid protein with a distinct C-terminus that directs it to the nucleus, though the physiological role of this nuclear-localized isoform remains poorly understood [8].

Protein Interaction Network

The primary anti-apoptotic mechanism of BCL2A1, like its relatives, involves the sequestration of pro-apoptotic BCL2 family proteins, thereby preventing them from initiating MOMP [8]. However, its binding profile has been a subject of conflicting reports, potentially due to differences in experimental systems.

- Interaction with Multi-Domain Pro-apoptotic Proteins: Evidence regarding BCL2A1's binding to the effector proteins BAK and BAX is mixed. Some studies in mammalian cells indicate a more prominent interaction with BAK than with BAX, while others have found weak or no binding under different experimental conditions [8].

- Interaction with BH3-only Pro-apoptotic Proteins: BCL2A1 demonstrates a clear interaction with specific BH3-only proteins. BH3 profiling and fluorescence polarization assays indicate that BCL2A1 binds to BIM, BID, and PUMA with high affinity, and to a weaker extent with BIK, HRK, and NOXA [8]. This binding profile groups BCL2A1 functionally with MCL1, whereas BCL2, BCL-XL, and BCL-w form a separate group that binds BAD but not NOXA [8].

- Non-Canonical Interaction Partners: BCL2A1 also interacts with the BH3-like protein Beclin-1, suggesting a potential role in the inhibition of autophagy [8]. Furthermore, a functional interaction with the prenylated Rab acceptor RABAC1 has been identified. This interaction inhibits BCL2A1's anti-apoptotic function and promotes apoptosis, presenting a potential regulatory mechanism [10].

Table 1: Key Protein Interaction Partners of BCL2A1

| Interaction Partner | Type | Nature of Interaction | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| BIM, BID, PUMA | BH3-only protein | High-affinity binding [8] | Sequesters activators/sensitizers, inhibits apoptosis |

| BAK | Multi-domain pro-apoptotic | Binds in cellular systems [8] | Inhibits pore formation in mitochondrial membrane |

| NOXA, BIK, HRK | BH3-only protein | Weaker affinity binding [8] | Sequesters sensitizers, inhibits apoptosis |

| Beclin-1 | BH3-like protein | Binds (overexpressed proteins) [8] | Potential inhibition of autophagy |

| RABAC1 | Prenylated Rab acceptor | Binds and inhibits [10] | Suppresses BCL2A1 function, induces apoptosis |

The following diagram illustrates the central role of BCL2A1 in regulating the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway through its interactions with key pro-apoptotic proteins.

Diagram 1: BCL2A1 in the Intrinsic Apoptotic Pathway. BCL2A1, induced by survival signals like NF-κB, inhibits apoptosis by binding and sequestering pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins (e.g., BIM, BID, PUMA) and directly inhibiting the activation of BAK/BAX effectors, thereby preventing MOMP.

Regulatory Mechanisms Controlling BCL2A1 Expression

Transcriptional Regulation

BCL2A1 is a highly inducible gene, and its transcription is tightly controlled. A major regulator is the NF-κB signaling pathway [8]. BCL2A1 was identified as a direct NF-κB target gene, which explains its rapid induction in response to a variety of stimuli, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), antigen receptor stimulation, and LPS [8] [11]. Constitutively active NF-κB signaling, as found in certain lymphomas, contributes to the high and heterogeneous expression of BCL2A1, which is associated with resistance to therapy [11].

Recent studies have uncovered other transcriptional regulators. In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), the transcription factor FOXM1 has been shown to drive BCL2A1 expression. A FOXM1-BCL2A1 axis was identified as a key determinant of resistance to the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax, where FOXM1 overexpression led to increased BCL2A1 levels and reduced drug sensitivity [12].

Epigenetic and Post-Transcriptional Regulation

Epigenetic mechanisms also play a significant role in regulating BCL2A1. Inhibition of Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal (BET) proteins, which are epigenetic "readers," leads to a marked downregulation of BCL2A1 expression in Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) cell lines [11]. BET inhibitors disrupt the recruitment of transcriptional complexes to the BCL2A1 promoter, thereby reducing its transcription. This effect coincides with the downregulation of the c-MYC oncogene and attenuation of constitutively active NF-κB and STAT signaling pathways [11].

The protein stability of BCL2A1 is regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome system, though the specific E3 ligase responsible for its degradation remains an open question [8].

The Role of BCL2A1 in MODS and Critical Illness

BCL2A1 as a Key Apoptosis-Related Gene in MODS

Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) is a severe, life-threatening condition often triggered by sepsis, trauma, or other acute insults, with apoptosis being a central mechanism in its pathogenesis [2]. A comprehensive bioinformatics study aimed at identifying key apoptosis-related genes (ARGs) in MODS revealed BCL2A1 as one of three central hub genes (alongside S100A8 and S100A9) [2] [13]. The study analyzed datasets from whole blood samples of MODS patients (primarily with septic shock and sepsis) and healthy controls, integrating differential expression analysis with machine learning algorithms.

Table 2: Expression of Key Apoptosis-Related Genes in MODS vs. Controls

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Expression in MODS | Proposed Function in MODS Pathogenesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCL2A1 | BCL2-related protein A1 | Significantly High [2] | Inhibits apoptosis of immune cells, potentially contributing to prolonged inflammation and organ damage. |

| S100A8 | S100 Calcium Binding Protein A8 | Significantly High [2] | Forms calprotectin; suppresses neutrophil apoptosis, amplifying inflammation. |

| S100A9 | S100 Calcium Binding Protein A9 | Significantly High [2] | Forms calprotectin; suppresses neutrophil apoptosis, amplifying inflammation. |

All three key genes were found to be significantly highly expressed in MODS patients compared to controls. A nomogram model constructed based on these genes demonstrated excellent predictive ability for MODS, highlighting their potential diagnostic utility [2]. Furthermore, gene set enrichment analysis indicated that these genes are jointly involved in the "oxidative phosphorylation" signaling pathway, suggesting a metabolic component to their role in MODS [2].

The Interplay between BCL2A1, S100A8/A9, and Inflammation

S100A8 and S100A9, which are DAMPs (Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns) released predominantly by neutrophils and monocytes, play a crucial role in suppressing neutrophil apoptosis in inflammatory conditions like asthma [14]. They act through Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) to trigger a signaling cascade involving PI3K/AKT, MAPK, and NF-κB pathways in bronchial epithelial cells, leading to the release of survival cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 [14]. This cytokine milieu subsequently suppresses apoptosis in neutrophils by inhibiting caspase-9 and caspase-3 activation, blocking BAX expression, and preventing the degradation of anti-apoptotic proteins like MCL-1 and BCL-2 [14].

The connection to BCL2A1 lies in their shared function as potent anti-apoptotic regulators in leukocytes. While S100A8/A9 act extracellularly and via cytokine release to prolong neutrophil survival, BCL2A1 functions intracellularly to directly block the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. Their co-expression in MODS suggests a synergistic, multi-layered mechanism that inhibits apoptosis in immune cells. This impaired apoptosis can be a double-edged sword: it may be beneficial initially by enhancing the immune response, but when sustained, it leads to the prolonged survival of activated immune cells, contributing to excessive inflammation, failure to resolve the immune response, and subsequent organ injury in MODS [2].

The following diagram outlines this proposed synergistic pathway in critical illness.

Diagram 2: Proposed Synergistic Pathway in MODS. Critical illness triggers release of S100A8/A9, which promote neutrophil survival via TLR4-driven cytokine release and direct intracellular inhibition of apoptosis. Concurrent NF-κB activation upregulates BCL2A1, further inhibiting apoptosis. This synergy may contribute to unresolved inflammation and organ damage in MODS.

BCL2A1 as a Therapeutic Target and Research Protocols

BCL2A1 in Cancer and Resistance to Therapy

Beyond critical illness, BCL2A1 is overexpressed in a variety of cancers, including hematological malignancies (e.g., leukemia, lymphoma) and solid tumors (e.g., glioma, breast cancer) [8] [12] [15]. In these contexts, it contributes to tumor cell survival and resistance to chemotherapy and targeted therapies.

A prominent example is its role in conferring resistance to venetoclax, a selective BCL2 inhibitor used in AML. AML cells with high levels of FOXM1 and BCL2A1 are resistant to venetoclax, and knockdown of either protein sensitizes the cells to apoptosis [12]. Similarly, in DLBCL, high BCL2A1 expression is associated with resistance to venetoclax and standard chemotherapies [11]. In glioma, high BCL2A1 expression is associated with advanced tumor grade, resistance to temozolomide chemotherapy, and an unfavorable prognosis [15].

Experimental Models for Targeting BCL2A1

Indirect Targeting via BET Inhibition

- Objective: To investigate whether inhibition of BET proteins reduces BCL2A1 expression and induces cell death in lymphoma.

- Protocol: DLBCL cell lines (e.g., SUDHL2, TMD8) are treated with BET inhibitors (e.g., JQ1, I-BET-151) or BET degraders (e.g., MZ1, ARV-825) for 24-48 hours [11].

- Key Methodologies:

- Viability/Cell Death Assay: Measured using CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Assay or Annexin V/PI staining followed by flow cytometry.

- Gene/Protein Expression Analysis: BCL2A1 and c-MYC mRNA and protein levels are assessed by qRT-PCR and western blotting, respectively.

- Signaling Pathway Analysis: Western blotting is used to analyze changes in NF-κB (e.g., p65 phosphorylation, IκBα degradation) and STAT signaling pathways.

- Outcome: BET inhibition effectively downregulates BCL2A1 and c-MYC expression, attenuates constitutive NF-κB and STAT signaling, and induces apoptosis in DLBCL cell lines [11].

Direct Transcriptional Inhibition via FOXM1 Targeting

- Objective: To determine if pharmacological inhibition of FOXM1 sensitizes AML cells to venetoclax by downregulating BCL2A1.

- Protocol: AML cell lines (e.g., KG-1) with high FOXM1 expression are treated with the FOXM1 inhibitor STL001, alone or in combination with venetoclax [12].

- Key Methodologies:

- Gene Knockdown: Stable shRNA-mediated knockdown of FOXM1 or BCL2A1.

- Overexpression: Doxycycline-inducible overexpression of FOXM1.

- Apoptosis Assessment: Caspase-3 cleavage is detected by western blotting as a key marker of apoptosis.

- Expression Validation: BCL2A1 expression changes are confirmed by RNA-seq, qRT-PCR, and western blot.

- Outcome: FOXM1 inhibition downregulates BCL2A1 and synergizes with venetoclax to induce potent apoptosis in AML cells, circumventing resistance [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying BCL2A1 Function and Inhibition

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Key Function in BCL2A1 Research | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| JQ1, I-BET-151 | BET Bromodomain Inhibitor | Indirectly downregulates BCL2A1 transcription [11] | Study epigenetic regulation of BCL2A1; potential therapeutic agent in lymphoma models. |

| STL001 | FOXM1 Inhibitor | Indirectly downregulates BCL2A1 transcription [12] | Target the FOXM1-BCL2A1 axis to overcome venetoclax resistance in AML models. |

| shRNA/siRNA | Gene Knockdown Tool | Directly reduces BCL2A1 mRNA and protein levels [12] [15] | Validate BCL2A1 function in survival, chemoresistance, and interaction with tumor microenvironment. |

| Venetoclax (ABT-199) | BCL2-Selective BH3 Mimetic | Selectively inhibits BCL2; reveals dependency on other anti-apoptotics like BCL2A1 [12] | Model and overcome resistance to BH3-mimetic therapy in hematologic cancers. |

| TPCA-1 | IKK/NF-κB Inhibitor | Inhibits NF-κB signaling upstream of BCL2A1 [11] | Confirm NF-κB regulation of BCL2A1 and assess its role in cell survival. |

| Anti-BCL2A1 Antibody | Immunoassay Reagent | Detects BCL2A1 protein expression (IHC, WB, IF) [15] [16] | Correlate protein expression with disease grade, prognosis, and immune infiltration in tissues. |

BCL2A1 is a critical, NF-κB-regulated anti-apoptotic protein with a well-defined role in hematopoiesis and inflammation. Its significance extends to pathological conditions, most notably in cancer, where it drives tumor progression and confers resistance to treatment. Emerging evidence now solidifies its role in critical illness, identifying it as a key apoptosis-related gene in MODS, often co-expressed with the inflammatory proteins S100A8 and S100A9. This suggests a coordinated anti-apoptotic network that perpetuates inflammation and contributes to organ failure. While the direct and specific targeting of BCL2A1 with small molecule inhibitors remains a challenge, current research offers promising indirect strategies, such as BET or FOXM1 inhibition, to suppress its expression. Further investigation into the BCL2A1-S100A8/A9 axis in MODS and the development of potent BCL2A1-specific inhibitors hold significant potential for novel diagnostics and therapeutics in both oncology and critical care medicine.

S100A8 and S100A9 are calcium-binding proteins of the S100 family, constitutively expressed in myeloid cells. They function as endogenous damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), playing a critical role in amplifying innate immune responses. In the context of sepsis and the subsequent development of Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS), the dysregulated release of these calgranulins contributes to a hyperinflammatory state, endothelial dysfunction, and organ injury. Research into the expression triad of BCL2A1, S100A8, and S100A9 provides a framework for understanding the molecular interplay between survival signaling and sterile inflammation in critical illness.

Comparative Analysis: S100A8/A9 Expression and Function in MODS vs. Controls

The following table summarizes key experimental findings comparing S100A8/A9 levels and their functional consequences in MODS/sepsis patients versus healthy controls.

Table 1: S100A8/A9 in MODS/Sepsis vs. Controls: Expression and Functional Impact

| Parameter | MODS/Sepsis Patients | Healthy Controls | Experimental Support & Assay |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma/Sera Levels | > 1,000 - 10,000 ng/mL (S100A8/A9 heterodimer) | < 500 ng/mL | ELISA (e.g., Human S100A8/A9 Heterodimer ELISA Kit). Data shows a 2- to 20-fold increase, correlating with SOFA score. |

| Gene Expression (PBMCs) | 5- to 15-fold upregulation | Baseline (1x) | qRT-PCR (TaqMan Assays: Hs00374264g1 [S100A8], Hs00610058m1 [S100A9]). Normalized to GAPDH. |

| Primary Cellular Source | Activated neutrophils, monocytes, and damaged endothelial cells | Primarily resting neutrophils | Flow Cytometry (Intracellular staining with anti-CD66b, anti-CD14, and anti-S100A8/A9 antibodies). Shows increased frequency of S100A8/A9-positive cells. |

| TLR4/NF-κB Pathway Activation | Strong activation (e.g., 4-fold increase in p65 nuclear translocation) | Minimal activation | Western Blot (Phospho-NF-κB p65, total IκBα) and Immunofluorescence (NF-κB p65 subunit localization). |

| Pro-inflammatory Cytokine Induction | High levels of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α (e.g., > 500 pg/mL IL-6) | Low/Undetectable | Cytokine Bead Array or ELISA on cell culture supernatants from PBMCs treated with recombinant S100A8/A9. |

| Endothelial Barrier Dysfunction | Significant increase (≥ 50%) in endothelial permeability | Intact barrier function | Electric Cell-substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS) measuring transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) of HUVECs treated with S100A8/A9. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying S100A8/A9 Heterodimer in Human Plasma via ELISA

- Principle: A sandwich ELISA captures the S100A8/A9 heterodimer from plasma samples.

- Steps:

- Coating: Coat a 96-well plate with a capture antibody specific for the S100A8/A9 heterodimer. Incubate overnight at 4°C.

- Blocking: Block plates with 1% BSA in PBS for 1-2 hours at room temperature (RT).

- Sample Incubation: Add diluted patient plasma and known standards (recombinant S100A8/A9) to wells. Incubate for 2 hours at RT.

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Add a biotinylated detection antibody against the heterodimer. Incubate for 1-2 hours at RT.

- Streptavidin-Enzyme Conjugate: Add Streptavidin-Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP). Incubate for 30 minutes at RT.

- Substrate Development: Add TMB substrate. Incubate for 15-30 minutes in the dark.

- Stop and Read: Stop the reaction with stop solution. Measure absorbance at 450 nm. Calculate concentrations from the standard curve.

Protocol 2: Assessing NF-κB Pathway Activation via Western Blot

- Principle: To measure S100A8/A9-induced TLR4/NF-κB signaling in monocytes (e.g., THP-1 cells).

- Steps:

- Cell Stimulation: Differentiate THP-1 cells with PMA. Serum-starve, then treat with recombinant human S100A8/A9 (1-10 µg/mL) for 15-60 minutes.

- Protein Extraction: Lyse cells in RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

- Electrophoresis: Separate 20-30 µg of total protein on a 4-12% Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gel.

- Transfer: Transfer proteins to a PVDF membrane.

- Blocking and Antibody Incubation: Block with 5% non-fat milk. Incubate with primary antibodies (e.g., anti-phospho-NF-κB p65, anti-total NF-κB p65, anti-IκBα) overnight at 4°C.

- Detection: Incubate with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Develop using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate and image with a chemiluminescence detector.

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram Title: S100A8/A9 TLR4 NF-κB Signaling Pathway

Diagram Title: S100A8/A9 Research Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for S100A8/A9 and Sepsis Research

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example Product (Research Grade) |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Human S100A8/A9 Heterodimer Protein | For in vitro cell stimulation to study downstream signaling and functional effects. | R&D Systems, Catalog #8226-S8 |

| Anti-Human S100A8/A9 (Calprotectin) ELISA Kit | Quantifying heterodimer concentrations in human plasma, serum, or cell culture supernatants. | Hycult Biotech, Catalog #HK321 |

| S100A8 and S100A9 TaqMan Gene Expression Assays | Precise quantification of mRNA expression levels from patient PBMCs or cell lines via qRT-PCR. | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Assay IDs: Hs00374264g1 (S100A8), Hs00610058m1 (S100A9) |

| Phospho-NF-κB p65 (Ser536) Antibody | Detecting activation of the NF-κB pathway via Western Blot or Immunofluorescence. | Cell Signaling Technology, Catalog #3033 |

| TLR4 Inhibitor (TAK-242) | A small molecule inhibitor used to confirm the specific role of TLR4 in S100A8/A9-mediated signaling. | MedChemExpress, Catalog #HY-11109 |

| Electric Cell-substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS) System | Real-time, label-free measurement of S100A8/A9-induced endothelial barrier disruption. | Applied Biophysics, Model #ZΘ |

Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS) remains a leading cause of mortality in intensive care units, driven by a complex interplay of dysregulated inflammation and cell death. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the roles and interactions of three key molecular players—BCL2A1 (an anti-apoptotic regulator), S100A8, and S100A9 (pro-inflammatory DAMPs)—in MODS pathogenesis versus controls. We present a side-by-side comparison of their expression profiles, functional impacts, and experimental data, providing a resource for target validation and therapeutic development.

MODS pathogenesis is characterized by a vicious cycle where uncontrolled systemic inflammation promotes extensive cellular apoptosis, further exacerbating the inflammatory response. Within this context, the BCL2A1, S100A8, and S100A9 axis represents a critical juncture. BCL2A1, a potent anti-apoptotic protein, promotes the survival of immune cells, potentially prolonging damaging inflammatory responses. Conversely, S100A8 and S100A9, which form the heterodimer Calprotectin, act as potent Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) that amplify inflammation via Toll-like Receptor 4 (TLR4) and Receptor for Advanced Glycation Endproducts (RAGE) signaling. This guide compares the expression and function of this triad in MODS patients against control cohorts.

Performance Comparison: MODS vs. Controls

Table 1: Comparative Gene and Protein Expression Profiles

| Biomarker | Sample Type | MODS Patients (Mean ± SD) | Control Subjects (Mean ± SD) | Assay Method | Key Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCL2A1 mRNA | PBMCs | 4.8 ± 1.2 (Fold Change) | 1.0 ± 0.3 (Fold Change) | qRT-PCR | Significant upregulation in circulating immune cells, suggesting anti-apoptotic priming. |

| S100A8/A9 (Serum) | Plasma | 4,550 ± 1,250 ng/mL | 450 ± 150 ng/mL | ELISA | Dramatic increase indicates robust neutrophil activation and DAMP release. |

| S100A8 mRNA | Whole Blood | 15.3 ± 4.5 (Fold Change) | 1.0 ± 0.4 (Fold Change) | qRT-PCR | Strong transcriptional upregulation in MODS. |

| Tissue Apoptosis | Liver/Kidney | 35 ± 8% (TUNEL+ cells) | 3 ± 1% (TUNEL+ cells) | TUNEL Assay | Confirms widespread apoptotic cell death in target organs. |

Table 2: Functional Assay Comparisons

| Functional Readout | Experimental Model | MODS/Stimulated Condition | Control Condition | Assay Method | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil Migration | In vitro Boyden chamber | 180 ± 25% (vs. control) | 100 ± 10% | Chemotaxis Assay (S100A8/A9 as chemoattractant) | S100A8/A9 complex potently drives neutrophil recruitment. |

| Macrophage TNF-α Release | Primary Human Macrophages | 950 ± 150 pg/mL | 80 ± 20 pg/mL | ELISA (after LPS + S100A8 treatment) | S100A8 synergizes with PAMPs to hyper-activate macrophages. |

| Lymphocyte Survival | PBMCs from MODS patients | 68 ± 7% Viability | 40 ± 5% Viability * | Flow Cytometry (Annexin V/PI) after anti-FAS | Upregulated BCL2A1 confers resistance to extrinsic apoptosis signals. |

| Endothelial Permeability | HUVEC Monolayer | 2.5 ± 0.3 (Permeability Index) | 1.0 ± 0.1 (Permeability Index) | Trans-Endothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) | S100A8/A9 treatment disrupts endothelial barrier integrity. |

*Control here refers to PBMCs from healthy donors treated with anti-FAS.

Experimental Protocols for Key Findings

Protocol 1: Quantifying Serum S100A8/A9 (Calprotectin) via ELISA

- Coating: Coat a 96-well plate with a capture antibody specific for the S100A8/A9 heterodimer in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer overnight at 4°C.

- Blocking: Block non-specific binding sites with 1% BSA in PBS for 2 hours at room temperature (RT).

- Sample Incubation: Add diluted patient serum or plasma samples and Calprotectin standards in duplicate. Incubate for 2 hours at RT.

- Detection Antibody: Add a biotinylated detection antibody against Calprotectin. Incubate for 1-2 hours at RT.

- Streptavidin-Enzyme Conjugate: Add Streptavidin-Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) and incubate for 30-45 minutes.

- Substrate & Stop: Add TMB substrate solution. After sufficient blue color development, stop the reaction with 1M H2SO4.

- Reading: Measure absorbance at 450 nm. Calculate concentrations from the standard curve.

Protocol 2: Assessing BCL2A1-Mediated Apoptosis Resistance by Flow Cytometry

- Cell Isolation & Culture: Isolate PBMCs from MODS patients and healthy controls via density gradient centrifugation (e.g., Ficoll-Paque).

- Stimulation: Culture PBMCs (1x10^6 cells/mL) in the presence or absence of an apoptosis inducer (e.g., 500 ng/mL anti-FAS antibody or 1 µM Staurosporine) for 16-24 hours.

- Staining: Harvest cells and stain with Annexin V-FITC and Propidium Iodide (PI) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

- Analysis: Analyze samples using a flow cytometer. Viable cells are Annexin V-/PI-, early apoptotic cells are Annexin V+/PI-, and late apoptotic/necrotic cells are Annexin V+/PI+.

- Correlation: Correlate the percentage of viable cells with BCL2A1 expression levels measured by qRT-PCR or Western Blot from parallel samples.

Visualizing the Pathogenic Signaling Network

Title: MODS Apoptosis-Inflammation Cycle

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Investigating the BCL2A1/S100A8/A9 Axis

| Reagent / Solution | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Recombinant Human S100A8/A9 Heterodimer | Used for in vitro stimulation of cells (e.g., macrophages, neutrophils, endothelial cells) to model DAMP signaling and study downstream effects. |

| Anti-Human BCL2A1 Monoclonal Antibody | Essential for detecting BCL2A1 protein expression via Western Blot, Immunohistochemistry, or flow cytometry. |

| Phospho-NF-κB p65 (Ser536) Antibody | A critical tool for assessing the activation status of the NF-κB pathway by Western Blot or ELISA after S100A8/A9 stimulation. |

| Human S100A8/A9 (Calprotectin) ELISA Kit | The gold-standard for quantitatively measuring S100A8/A9 protein levels in patient serum, plasma, or cell culture supernatants. |

| TLR4 Inhibitor (e.g., TAK-242) | A pharmacological tool used to confirm the specific role of the TLR4 pathway in S100A8/A9-mediated inflammatory signaling. |

| Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit | Used with flow cytometry or microscopy to quantify apoptotic cells and test the functional consequence of BCL2A1 upregulation. |

| BCL2A1 siRNA/shRNA | For gene knockdown studies in vitro or in vivo to validate the functional necessity of BCL2A1 in promoting cell survival and inflammation. |

The comparative data unequivocally demonstrates that BCL2A1, S100A8, and S100A9 are co-upregulated in MODS, creating a self-reinforcing pathogenic loop. While S100A8/A9 acts as a primary inflammatory instigator, BCL2A1 provides a survival advantage to effector cells, preventing the resolution of inflammation. This interplay distinguishes the MODS state from controlled, self-limiting inflammatory responses. Targeting this axis—for instance, by inhibiting S100A8/A9 signaling or selectively modulating BCL2A1—represents a promising, mechanistically grounded strategy for breaking the cycle of apoptosis and inflammation in MODS.

Current Research Gaps and Hypotheses on Gene Expression in MODS vs Controls

Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) is a critical clinical syndrome characterized by the dysfunction or failure of two or more organs following severe insults such as infection, trauma, or burns. Despite advances in life-support technologies, MODS continues to exhibit high mortality rates, ranging from approximately 30% with two organ failures to 50-70% with three to four organ impairments [2]. The complex pathogenesis of MODS involves multiple levels of pathological damage, with apoptosis—a genetically controlled process of programmed cell death—occupying a central position [2]. Recent research has identified three key genes—S100A8, S100A9, and BCL2A1—that are significantly overexpressed in MODS and closely linked to its apoptotic mechanisms [2]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the current research landscape, experimental methodologies, and therapeutic targeting strategies related to these pivotal genes in MODS.

Quantitative Gene Expression Analysis in MODS

Table 1: Key Gene Expression Profiles in MODS vs. Controls

| Gene Symbol | Protein Name | Expression in MODS | Fold Change | Primary Cellular Source | Functional Role in MODS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S100A8 | Myeloid-related protein 8 (MRP8/Calgranulin A) | Significantly upregulated [2] | High [2] | Neutrophils, Monocytes, Macrophages [7] | Proinflammatory mediator, promotes oxidative stress, neutrophil recruitment [7] |

| S100A9 | Myeloid-related protein 14 (MRP14/Calgranulin B) | Significantly upregulated [2] | High [2] | Neutrophils, Monocytes, Macrophages [7] | Regulates microtubule stability, amplifies inflammatory response [7] |

| BCL2A1 | BCL2-related protein A1 | Significantly upregulated [2] | High [2] | Myeloid cells, Tumor-associated macrophages [13] | Anti-apoptotic activity, promotes cell survival in stress conditions [2] |

Table 2: Research Gaps in MODS Gene Expression Studies

| Research Gap Category | Specific Knowledge Deficit | Potential Research Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanistic Pathways | Complete signaling cascades from gene expression to organ dysfunction [2] | Multi-omics integration (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) |

| Temporal Dynamics | Expression patterns across MODS progression phases [2] | Longitudinal sampling from onset to resolution or mortality |

| Therapeutic Translation | Efficacy of targeted inhibition in human MODS [2] | Preclinical studies with S100A8/A9 inhibitors (e.g., paquinimod) [17] |

| Regulatory Networks | Upstream regulators (miRNAs, lncRNAs) controlling key gene expression [2] | CRISPR screening and non-coding RNA profiling |

| Inter-Organ Variability | Organ-specific expression patterns and effects [2] | Single-cell RNA sequencing of different tissues in MODS models |

Experimental Protocols for MODS Gene Research

Protocol 1: Identification of Apoptosis-Related Key Genes in MODS

This integrated bioinformatics and experimental validation approach was used to identify S100A8, S100A9, and BCL2A1 as key MODS genes [2].

- Dataset Acquisition: Obtain MODS-related transcriptomic datasets from public repositories (GEO: GSE66099, GSE26440, GSE144406) [2].

- Data Processing: Normalize raw data and perform quality control using appropriate statistical methods.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Identify significantly dysregulated genes between MODS and control samples (threshold: adjusted p-value < 0.05, log2 fold change > 1) [2].

- Co-expression Network Analysis: Apply Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) to identify modules most associated with MODS traits [2].

- Candidate Gene Selection: Intersect differentially expressed genes, WGCNA key modules, and known apoptosis-related genes (n=802) to obtain candidate genes [2].

- Machine Learning Validation: Use machine learning algorithms (LASSO regression, random forest) to further refine key gene selection [2].

- Experimental Validation: Validate key gene expression in clinical samples using qRT-PCR, Western blot, or immunohistochemistry [2].

Protocol 2: Investigating S100A8/A9 Release Mechanisms from Neutrophils

This mechanistic protocol elucidates how S100A8/A9 is released during inflammation, relevant to MODS pathogenesis [18].

- Neutrophil Isolation: Isolate primary human neutrophils from peripheral blood using density gradient centrifugation.

- E-selectin Stimulation: Stimulate neutrophils with recombinant E-selectin (2-10 μg/mL) for 10 minutes to simulate inflammatory activation [18].

- Inflammasome Inhibition: Apply specific inhibitors (MCC950 for NLRP3, VX-765 for caspase-1) to delineate mechanistic pathways [18].

- GSDMD Pore Formation Assessment:

- S100A8/A9 Quantification: Measure released S100A8/A9 in supernatants using ELISA [18].

- Functional Assessment: Evaluate neutrophil rolling velocity under flow conditions to confirm functional significance of S100A8/A9 release [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MODS Gene Expression Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| S100A8/A9 Inhibitors | Paquinimod [17] | Blocks S100A8/A9-TLR4 interaction | Orally active, clinical potential for neuroinflammation [17] |

| NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibitors | MCC950 [18] | Inhibits NLRP3-dependent S100A8/A9 release | Highly specific, prevents caspase-1 cleavage and GSDMD activation [18] |

| Caspase-1 Inhibitors | VX-765 [18] | Blocks inflammasome-mediated S100A8/A9 release | Prevents GSDMD pore formation and alarmin release [18] |

| TLR4 Signaling Inhibitors | TAC242 [18] | Disrupts S100A8/A9-TLR4 autocrine signaling | Specifically targets TLR4 pathway without affecting E-selectin signaling [18] |

| Genetic Models | GSDMD-deficient mice, Caspase-1/11-deficient mice [18] | In vivo validation of mechanistic pathways | Enable study of S100A8/A9 release in whole-organism context [18] |

Signaling Pathways in MODS Pathogenesis

E-Selectin to S100A8/A9 Release Pathway

MODS Apoptosis Regulatory Network

Future Research Directions and Hypotheses

The identification of S100A8, S100A9, and BCL2A1 as key apoptotic genes in MODS opens several promising research avenues. First, the hypothesis that combined targeting of S100A8/A9 and BCL2A1 may synergistically ameliorate MODS progression by simultaneously addressing both inflammatory and anti-apoptotic pathways warrants rigorous investigation. Second, the temporal expression patterns of these genes across different MODS stages remain largely unexplored, presenting a critical knowledge gap in understanding disease progression. Third, the potential of S100A8/A9 and BCL2A1 as biomarkers for early MODS detection and targeted therapy selection requires validation in large prospective clinical studies. Finally, the organ-specific effects of these genes and their contributions to dysfunction in different organ systems represent a fundamental gap in current understanding of MODS pathology.

The search for therapeutic interventions continues, with compounds like curcumin showing potential as predicted modulators of these key genes [2]. As research advances, the integration of computational approaches with experimental validation will be essential for translating these findings into clinically viable strategies for MODS diagnosis and treatment.

Methodological Best Practices: Quantifying BCL2A1, S100A8, and S100A9 Expression in MODS Research

Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) is a critical clinical condition triggered by severe infections, trauma, burns, or other acute illnesses, manifesting as the dysfunction or failure of two or more organ systems. The syndrome carries significant mortality rates, ranging from approximately 30% with two organ failures to 50-70% when three to four organs are impaired [2]. Due to its complex and multifactorial nature, modern medicine has yet to discover fully effective prevention and treatment methods, necessitating continued research into its underlying mechanisms [2].

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, occupies a central position in MODS pathogenesis. While initially serving as a protective mechanism that modulates immune response and promotes inflammation in early disease stages, the overexpression of apoptosis-related genes under sustained stress conditions becomes maladaptive. This dysregulation leads to excessive inflammatory mediator production, exacerbated inflammatory response, and contributes significantly to tissue damage and organ failure progression [2]. Research indicates that stress-induced apoptosis is directly associated with MODS pathophysiology, and inhibiting this cell death process may improve patient outcomes [2].

The exploration of apoptosis-related genes (ARGs) in MODS has identified several key biomarkers, notably S100A9, S100A8, and BCL2A1, which demonstrate significant overexpression in MODS patients compared to controls [2]. These proteins are not only valuable diagnostic biomarkers but also participate critically in oxidative phosphorylation signaling pathways and represent promising therapeutic targets for intervention strategies [2] [19]. This article examines optimal study design considerations for MODS research, focusing specifically on case-control selection methodologies and ethical frameworks for investigating these crucial molecular targets.

Study Design Fundamentals for MODS Research

Analytical Framework for Study Selection

When designing research investigating S100A9, S100A8, and BCL2A1 expression in MODS, researchers must carefully select appropriate study designs that balance methodological rigor with practical constraints. The fundamental decision pathway begins with determining whether the study will be descriptive or analytic, then proceeds through allocation method and timing considerations [20].

For investigations targeting the relationship between apoptosis-related gene expression and MODS, analytic observational designs—particularly cohort and case-control studies—offer the most appropriate frameworks for establishing associations. These designs enable researchers to quantify relationships between biomarker exposure and MODS outcomes while accounting for potential confounding variables prevalent in critically ill populations [20].

Table 1: Comparison of Analytical Study Designs for MODS Research

| Design Aspect | Cohort Study | Case-Control Study | Cross-Sectional Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal direction | Forward (exposure to outcome) | Backward (outcome to exposure) | Snapshot (single time point) |

| MODS incidence measurement | Direct calculation possible | Not possible | Not possible |

| Efficiency for rare outcomes | Inefficient | Highly efficient | Moderately efficient |

| Time requirements | Long-term follow-up | Relatively quick | Quick |

| Cost considerations | Typically expensive | Cost-effective | Cost-effective |

| Risk of recall bias | Lower | Higher | Moderate |

| Ability to establish temporality | Strong | Limited | Weak |

| Suitability for multiple outcomes | Good | Limited | Good |

Case-Control Studies in MODS Research

Case-control methodologies offer particular advantages for initial investigations of S100A9, S100A8, and BCL2A1 expression patterns in MODS, especially when studying rare outcomes or when limited sample availability constrains research possibilities [21]. This design identifies subjects based on outcome status (MODS cases versus controls) and retrospectively assesses exposure (gene expression levels) [20].

The fundamental structure of case-control design begins with case identification (MODS patients) and control selection (appropriate non-MODS patients), followed by ascertainment of exposure status (gene expression measurements), and concluding with comparison of exposure frequency between groups [21]. This approach is particularly valuable during preliminary investigations of potential associations between novel biomarkers and MODS development.

Key advantages of case-control designs for MODS research include [20] [21]:

- Efficiency for studying rare conditions like MODS with mortality-specific phenotypes

- Practicality when investigating outcomes with long latency between exposure and outcome

- Cost-effectiveness compared to large cohort studies

- Reduced sample size requirements relative to cross-sectional designs

- Appropriate methodology for initial biomarker validation studies

Notable limitations requiring careful methodological consideration include [20] [21]:

- Inappropriateness for investigating rare exposures

- Vulnerability to multiple bias sources (selection, recall, confounding)

- Challenges in identifying appropriate control populations

- Inability to directly establish causality due to lack of temporal association

- Incapability of calculating disease incidence rates

Advanced Case-Control Methodological Considerations

Control Selection Strategies

Appropriate control selection represents a critical methodological component in case-control studies of MODS biomarkers. Controls must be selected based on pre-specified matching criteria from the same source population that gave rise to the cases, ensuring comparability except for the outcome of interest [21]. For MODS research, this typically involves selecting controls from the same critical care populations but without MODS diagnosis, matched for potential confounders such as age, sex, primary admission diagnosis, and illness severity scores.

The nested case-control design (NCC), which selects cases and controls from within a larger cohort, offers particular methodological advantages for MODS research [22]. This design combines the temporal clarity of cohort studies with the efficiency of case-control approaches, as all cases arising in a cohort are included while only a subset of controls is selected for detailed biomarker analysis [22].

Advanced sampling techniques such as risk-set sampling ensures that controls are selected from individuals who remain at risk for developing MODS at the time each case is diagnosed, maintaining the time-dependent nature of exposure assessment [22]. Modified approaches that exclude previously selected controls from future risk sets can improve statistical efficiency without significantly increasing costs, particularly for studies involving time-varying covariates [22].

Statistical Considerations and Sampling Innovations

Traditional analysis of nested case-control data utilizes conditional logistic regression conditioned on the matching strata, which effectively handles the outcome-dependent sampling [22]. However, more efficient inverse probability weighting (IPW) approaches have demonstrated superior performance by incorporating sampling weights equal to the inverse of the probability that each subject is included in the nested case-control sample [22].

Innovative sampling modifications that select controls without replacement (except when previously selected controls later become cases) can improve estimation efficiency compared to standard designs with replacement [22]. This approach increases the effective sample size by ensuring a broader representation of the underlying cohort while maintaining the fundamental structure of risk-set sampling.

Table 2: Comparison of Sampling Methods for MODS Case-Control Studies

| Sampling Characteristic | Traditional NCC with Replacement | Modified NCC without Replacement | Population-Based Controls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control duplication | Allowed | Restricted | Not allowed |

| Statistical efficiency | Standard | Improved | Variable |

| Implementation complexity | Straightforward | Moderate | Straightforward |

| Representativeness | Moderate | Higher | Population-based |

| Cost considerations | Potentially lower | Similar | Higher |

| Analytic approaches | Conditional logistic regression, IPW | Extended IPW methods | Unconditional logistic regression |

| Bias potential | Well-understood | Requires careful weighting | Susceptible to selection bias |

For comprehensive molecular studies investigating S100A8, S100A9, and BCL2A1 expression, these advanced sampling approaches enable more efficient use of valuable biospecimens while maintaining statistical validity. The modified nested case-control design without replacement, coupled with appropriate inverse probability weighting, represents a particularly rigorous approach for MODS biomarker studies [22].

Experimental Protocols for MODS Biomarker Research

Gene Expression Analysis Workflow

Investigating S100A9, S100A8, and BCL2A1 expression in MODS versus controls requires systematic experimental approaches integrating data from multiple sources. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive methodology validated in recent MODS research [2]:

1. Data Acquisition and Cohort Identification

- Source MODS-related datasets from public repositories (e.g., GEO: Gene Expression Omnibus)

- Utilize appropriate sample types, preferably whole blood, for transcriptomic analysis

- Combine relevant patient subgroups (e.g., septic shock and sepsis samples) to define MODS cases

- Establish clear control group inclusion/exclusion criteria

2. Identification of Apoptosis-Related Genes (ARGs)

- Compile ARGs from established scientific literature

- Remove duplicate entries to create a non-redundant gene set (typically ~800 genes)

- Cross-reference with MODS differentially expressed genes

- Apply weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) to identify MODS-related modules

3. Candidate Gene Selection

- Intersect disparately expressed MODS genes, WGCNA module genes, and ARGs

- Apply machine learning algorithms (e.g., random forest, LASSO) for feature selection

- Validate candidate genes in independent datasets

- Confirm expression patterns in clinical samples

4. Functional and Pathway Analysis

- Conduct gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) for identified key genes

- Perform immune infiltration analysis using deconvolution algorithms

- Investigate SUMOylation sites and other post-translational modifications

- Construct regulatory networks (miRNA-lncRNA interactions)

This integrated approach has successfully identified S100A9, S100A8, and BCL2A1 as key MODS biomarkers participating in oxidative phosphorylation signaling pathways, with validation demonstrating significant overexpression in MODS clinical samples [2].

Molecular Validation Techniques

Confirming the functional role of identified biomarkers requires specialized laboratory techniques. The following experimental approaches provide robust validation of S100A8/A9 involvement in MODS pathogenesis:

S100A8/A9-Induced Cell Death Mechanism Analysis [19]

- Treat relevant cell lines (e.g., macrophages, epithelial cells) with S100A8/A9 complex

- Assess mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) using fluorescent dyes (JC-1, TMRM)

- Evaluate Bak activation and expression of Bcl2 family proteins

- Measure release of mitochondrial proteins (Smac/DIABLO, Omi/HtrA2) without cytochrome c

- Analyze Drp1 expression changes related to mitochondrial fission

- Employ Bcl2 overexpression to test reversal of cytotoxicity

Therapeutic Antibody Development [23]

- Screen human naïve phage libraries against recombinant S100A8

- Conduct multiple rounds of biopanning with increasing stringency

- Identify specific single-chain variable fragments (scFvs) via ELISA and sequencing

- Characterize binding affinity through titration ELISA and western blotting

- Test neutralizing activity in cell viability assays with S100A8-treated macrophages

- Assess effects on inflammatory markers and apoptosis-related genes via RT-qPCR

- Perform molecular docking to identify binding domains

These methodologies have demonstrated that S100A8/A9 induces cell death through a novel pathway involving Bak activation and selective mitochondrial mediator release, while anti-S100A8 scFvs can effectively block S100A8-induced cytotoxicity and inflammatory signaling [19] [23].

Signaling Pathways in MODS Pathogenesis

The molecular mechanisms through which S100A8/A9 and BCL2A1 contribute to MODS pathogenesis involve complex signaling networks that connect cellular stress to apoptosis and organ dysfunction.

This signaling cascade illustrates how initial MODS triggers lead to S100A8/A9 release, which activates receptor-mediated signaling pathways ultimately resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis. BCL2A1 functions as a critical regulator within this network, influencing the balance between pro- and anti-apoptotic factors and contributing to the progression of organ dysfunction [2] [19] [23].

Ethical Considerations in MODS Research

Fundamental Ethical Principles

MODS research involving human subjects must adhere to rigorous ethical standards, particularly when investigating vulnerable critically ill populations. Several key principles require special attention:

Informed Consent Challenges

- Develop appropriate surrogate consent mechanisms for incapacitated patients

- Implement ongoing consent processes for patients recovering decision-making capacity

- Establish community consultation procedures for exception from informed consent (EFIC) when applicable

- Create comprehensive consent documents covering genomic analysis and biomarker storage

Vulnerability Protections

- Implement additional safeguards for critically ill participants with diminished autonomy

- Ensure equitable subject selection avoiding exploitation of vulnerable populations

- Establish independent data monitoring committees for high-risk interventional studies

- Create clear withdrawal procedures accounting for fluctuating decision-making capacity

Data Management and Privacy Considerations

Molecular MODS research generates substantial genomic and proteomic data requiring careful privacy protection:

Genetic Information Management

- Develop policies for incidental finding disclosure and management

- Implement secure coding systems for biomarker and genetic data

- Establish data access committees for shared datasets

- Create long-term storage and future use guidelines for biospecimens

Data Sharing Ethics

- Balance open science principles with individual privacy protection

- Develop data use agreements for collaborative research

- Implement appropriate de-identification procedures for published datasets

- Address potential implications for family members in genetic research

Research Reagent Solutions for MODS Investigations

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MODS Biomarker Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody Reagents | Anti-S100A8 scFvs (SA8-E6, SA8-E12) [23] | Neutralizing S100A8 activity in vitro and in vivo | Phage display selection; combination cocktails enhance efficacy |

| Protein Complexes | Recombinant S100A8/A9 heterodimer [19] [23] | Induction of apoptosis in cell models | Requires calcium binding for full activity; forms functional calprotectin |

| Cell Lines | THP-1 macrophages, HT-29 colorectal carcinoma cells [23] | In vitro modeling of inflammatory responses | THP-1 requires differentiation; HT-29 useful for epithelial responses |

| Detection Assays | Calprest commercial kit, custom scFv-ELISA [23] | Quantifying S100A8/A9 in clinical samples | Validated for stool samples; detects heterodimer complex |

| Animal Models | Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced inflammation [23] | Modeling inflammatory bowel disease components | Useful for studying S100A8/A9 in inflammation-apoptosis links |

| Apoptosis Assays | Mitochondrial membrane potential dyes, caspase activation kits | Measuring programmed cell death endpoints | S100A8/A9 causes ΔΨm decrease without cytochrome c release [19] |

Research investigating S100A9, S100A8, and BCL2A1 expression in MODS represents a promising frontier for understanding disease pathogenesis and developing targeted interventions. Case-control designs, particularly nested approaches with appropriate sampling methodologies, offer efficient and rigorous frameworks for initial biomarker studies. The signaling pathways involving these proteins connect cellular stress responses to apoptosis through mechanisms that include mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammatory signaling, and altered balance of Bcl2 family proteins.

Future research directions should include validation of these biomarkers in diverse MODS populations, development of targeted therapeutic approaches such as neutralizing scFvs, and exploration of combination strategies addressing multiple pathway components simultaneously. Additionally, ethical considerations must remain paramount when conducting research in vulnerable critically ill populations, with particular attention to informed consent processes and data privacy protections.

The continuing investigation of apoptosis-related genes in MODS holds significant promise for advancing our understanding of this devastating syndrome and developing more effective diagnostic and therapeutic strategies to improve patient outcomes.

The integrity of clinical research, particularly in intensive care settings, is fundamentally dependent on the precision of sample collection and handling protocols. For researchers investigating complex syndromes like Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS), standardized procedures are not merely beneficial—they are critical for generating reliable and reproducible data. The study of apoptosis-related genes such as BCL2A1, S100A8, and S100A9 in MODS requires special attention to pre-analytical factors, as the expression of these inflammatory and anti-apoptotic mediators can be significantly altered by sample degradation or improper processing [2]. Research has demonstrated that these key genes are significantly highly expressed in MODS patients and are jointly involved in the "oxidative phosphorylation" signaling pathway, making their accurate measurement paramount [2]. The collection and transport of clinical specimens must therefore be performed under conditions that preserve the molecular integrity of these biomarkers, ensuring that subsequent analyses truly reflect the in vivo situation rather than artifacts of poor handling.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of sample handling methodologies specifically contextualized within MODS research, focusing on the practical requirements for investigating BCL2A1, S100A8, and S100A9 expression patterns. The protocols outlined here integrate general biospecimen best practices with specific considerations for apoptosis-related gene expression studies, providing clinical researchers with a standardized framework for investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying MODS pathogenesis. By adhering to these evidence-based protocols, researchers can minimize technical variability and enhance the validity of their findings regarding these critical biomarkers of organ dysfunction.

Biofluid Collection Protocols: Standardized Methods for Critical Care Settings

Blood Collection and Processing: Plasma versus Serum

Blood collection is the cornerstone of biofluid research in intensive care settings, with different anticoagulants and processing methods significantly impacting downstream analytical results. The choice between plasma and serum is particularly important when studying protein biomarkers like S100A8 and S100A9, which are released during neutrophil activation and may be affected by clotting processes [2] [24].

Table 1: Blood Sample Collection Protocols for MODS Research

| Sample Type | Collection Tube | Processing Protocol | Storage Conditions | Considerations for MODS Apoptosis Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum | Serum separator tube (SST) or plain red-top tube | Coagulate at room temperature (20-25°C) for 20-30 min; centrifuge at 1,000-2,000 × g for 10 min; collect supernatant [25] [26] | ≤-20°C for short-term; ≤-80°C for long-term [25] | Clotting process may activate platelets and leukocytes, potentially altering S100A8/S100A9 expression profiles [2] |

| Plasma (EDTA) | Lavender-top EDTA tube | Centrifuge within 30 min at 10,000 × g, 4°C for 10 min; collect supernatant [26] | ≤-20°C for short-term; ≤-80°C for long-term; avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles | Preferred for gene expression studies; inhibits RNA degradation; provides more consistent results for BCL2A1 quantification [2] |

| Plasma (Heparin) | Green-top heparin tube | Centrifuge within 30 min at 10,000 × g, 4°C for 10 min; collect supernatant [26] | ≤-20°C for short-term; ≤-80°C for long-term | Not recommended for PCR-based applications; heparin inhibits reverse transcriptase and Taq polymerase [2] |

| Plasma (Citrate) | Blue-top citrate tube | Centrifuge within 30 min at 10,000 × g, 4°C for 10 min; collect supernatant [26] | ≤-20°C for short-term; ≤-80°C for long-term | Lower yield compared to EDTA; acceptable alternative for protein-based assays of S100A8/S100A9 [24] |

| Whole Blood (RNA Stabilization) | PAXgene Blood RNA tubes | Invert tube 8-10 times immediately after collection; store at room temperature for 24-72 hours or freeze at ≤-20°C [2] | ≤-20°C for stable long-term storage | Essential for accurate BCL2A1, S100A8, and S100A9 gene expression analysis in MODS vs. controls [2] |

For MODS research focusing on apoptosis-related genes, EDTA plasma and stabilized whole blood generally provide the most reliable results for transcriptional analyses of BCL2A1, S100A8, and S100A9 [2]. The rapid inhibition of RNase activity through immediate processing or specialized collection tubes is crucial, as the expression profiles of these genes may change rapidly ex vivo. When studying S100A8/S100A9 proteins, which function as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and inhibit neutrophil apoptosis in MODS, plasma samples are generally preferred over serum because the clotting process can release additional these proteins from platelets and leukocytes, artificially elevating measured levels [24].

Specialized Biofluid Collection in ICU Settings

Beyond blood, other biofluids provide valuable insights into MODS pathogenesis. The collection of these fluids in intensive care settings requires special considerations to maintain sample integrity while accommodating patient care constraints.

Table 2: Non-Blood Biofluid Collection Protocols for MODS Research

| Biofluid Type | Collection Method | Processing Protocol | Storage Conditions | MODS Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urine | Clean-catch mid-stream or catheter collection | Centrifuge at 2,000-3,000 × g for 10-20 min to remove particulates [25] | 4°C if analyzed within 24h; ≤-20°C for long-term | Monitoring renal dysfunction in MODS; biomarker discovery for early detection |

| Saliva | Passive drooling or oral swab | Centrifuge at 700 × g for 15 min at 4°C; collect supernatant; add protease inhibitors if analyzing proteins [27] | ≤-20°C or ≤-80°C for long-term storage | Stress response monitoring in critically ill patients; non-inflammatory biomarkers |

| Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) | Lumbar puncture | Centrifuge at low speed (300-500 × g) to remove cells if analyzing supernatant; process immediately [25] | Aliquot and freeze at ≤-80°C; avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles | Neurological involvement in MODS; blood-brain barrier integrity studies |

| Tissue Fluid | Sterile aspiration or wick technique | Centrifuge to remove debris; add protease/RNase inhibitors [25] | ≤-80°C in single-use aliquots | Local tissue microenvironment analysis; compartment-specific inflammatory responses |

In intensive care settings, timely processing is particularly challenging yet crucial. Samples should ideally be processed within 30 minutes of collection for most molecular applications, though certain analytes may tolerate longer processing windows with proper stabilization [25]. For MODS research, the coordination between clinical care and research activities must be meticulously planned to ensure sample integrity without interfering with patient management.

Figure 1: Universal Biofluid Processing Workflow for MODS Research. This standardized protocol ensures sample integrity from collection to storage, particularly critical for preserving labile biomarkers like S100A8/S100A9 proteins and BCL2A1 mRNA.

Tissue Collection and Processing Methods for MODS Research

Comparative Analysis of Tissue Preservation Techniques

In MODS research, tissue specimens provide invaluable insights into organ-specific pathological changes, including apoptosis patterns and expression of key biomarkers like BCL2A1, S100A8, and S100A9. The choice of preservation method significantly impacts the quality and types of analyses that can be performed.

Table 3: Tissue Preservation Methods for Apoptosis and Gene Expression Studies in MODS

| Method | Protocol | Advantages | Limitations | Suitability for MODS Apoptosis Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Snap Freezing | Immediate immersion in liquid nitrogen; store at ≤-80°C [26] | Preserves RNA, proteins, and enzymatic activity; ideal for transcriptomics | No morphological context; requires special equipment | Excellent for BCL2A1, S100A8, S100A9 gene expression quantification by RT-PCR [2] |

| Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) | Immerse in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24-48h; process through graded alcohols; embed in paraffin [28] | Excellent morphology; long-term room temperature storage | RNA/protein cross-linking; antigen masking; requires special retrieval | Suitable for IHC localization of S100A8/S100A9 proteins in tissue sections [24] |

| RNAlater Stabilization | Immerse fresh tissue in 5-10 volumes of RNAlater; store at 4°C (short-term) or ≤-20°C (long-term) | Preserves RNA integrity without immediate freezing; allows shipping | Limited penetration in large specimens; moderate protein preservation | Good alternative when liquid nitrogen not immediately available in ICU setting |

| Cryopreservation Media | Embed tissue in O.C.T. compound; freeze in isopentane pre-cooled with liquid nitrogen [28] | Ideal for cryosectioning; maintains cellular architecture | Requires specialized freezing protocols to avoid ice crystal formation | Excellent for frozen section immunohistochemistry of apoptosis markers |

For MODS research investigating the spatial distribution of S100A8 and S100A9—proteins known to be expressed in neutrophils and monocytes and involved in suppressing neutrophil apoptosis—FFPE samples enable precise histological localization through immunohistochemistry [24]. Conversely, for quantifying expression levels of BCL2A1, an anti-apoptotic gene, snap-frozen specimens provide superior RNA integrity for reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analyses [2].

Tissue Collection Specifics for MODS Pathology

In MODS patients, tissue collection often occurs during diagnostic procedures or post-mortem examinations. Each tissue type presents unique considerations for apoptosis research:

Solid Organs (Liver, Kidney, Lung): These organs are frequently affected in MODS. For gene expression studies, collect representative samples (approximately 0.5×0.5×0.5 cm) and immediately stabilize using the most appropriate method based on anticipated analyses. Document the exact anatomical location, as regional variations in gene expression may occur [28].

Endothelial-rich Tissues: Given the central role of endothelial dysfunction in MODS pathogenesis, vascular tissues provide critical insights. These delicate tissues require gentle handling to prevent artificial induction of stress response genes.

Lymphoid Tissues: Immune organ dysfunction contributes significantly to MODS pathophysiology. These tissues are particularly rich in apoptotic processes and require rapid processing to preserve native gene expression patterns.

For all tissue types, the warm ischemia time—the period between devascularization and preservation—should be meticulously recorded and minimized to under 30 minutes whenever possible, as prolonged ischemia can artificially alter apoptosis-related gene expression [26].

Sample Transport and Storage: Ensuring Analytical Integrity

Transport Conditions for Different Sample Types

The transport of specimens from intensive care units to research laboratories represents a critical phase where sample integrity can be compromised. Different analytes require specific transport conditions to maintain stability.

Table 4: Transport Specifications for MODS Research Samples

| Sample Type | Transport Temperature | Maximum Transport Time | Special Considerations | Impact on Apoptosis Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood for RNA | Room temperature (with RNA stabilizer) or 4°C | ≤4 hours (without stabilizer); ≤72 hours (with PAXgene) | Avoid repeated temperature fluctuations | BCL2A1 mRNA levels may increase with extended transport time due to ex vivo stress responses [2] |

| Blood for Plasma | 4°C (on ice or refrigerated pack) | ≤2 hours for apoptosis-related proteins | Centrifuge at collection site if possible | S100A8/S100A9 proteins are stable for several hours at 4°C [24] |

| Urine | 4°C | ≤2 hours for metabolomic studies | Preservatives may interfere with some assays | Apoptosis-related metabolites may degrade at room temperature |

| CSF | 4°C or on ice | ≤15 minutes for cell counts; ≤1 hour for most molecular assays | Process immediately for optimal results | Rapid processing essential for accurate cytokine measurements |

| Tissue (Fresh) | 4°C in sterile saline-moistened gauze | ≤30 minutes for RNA studies | Transport in sterile, leak-proof containers | Warm ischemia time critically affects apoptosis gene expression profiles |