Caspase Cascade Activation and Executioner Functions: Mechanisms, Regulation, and Therapeutic Targeting

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the caspase cascade, a cornerstone of programmed cell death (apoptosis) and inflammation.

Caspase Cascade Activation and Executioner Functions: Mechanisms, Regulation, and Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the caspase cascade, a cornerstone of programmed cell death (apoptosis) and inflammation. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational knowledge with contemporary research. The scope spans from the fundamental mechanisms of initiator and executioner caspase activation to advanced methodological approaches for studying caspase activity. It further addresses common challenges in experimental models, discusses the validation of caspase functions, and compares the specificity of different caspases. By integrating basic science with clinical applications, this review aims to serve as a critical resource for understanding caspase biology and its immense potential in developing novel therapeutics for cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and immune diseases.

The Core Machinery: Unraveling Initiator and Executioner Caspase Biology

Caspases are an evolutionarily conserved family of cysteine-dependent aspartate-specific proteases that serve as critical regulators of programmed cell death (PCD) and inflammation [1] [2]. These enzymes hydrolyze peptide bonds in their substrates after specific aspartic acid residues, utilizing a catalytic cysteine residue in their active site [3] [4]. Initially identified for their fundamental role in apoptosis, caspases are now recognized as master regulators of multiple cell death pathways, including pyroptosis and necroptosis, and play essential roles in development, immune responses, and cellular homeostasis [1] [2].

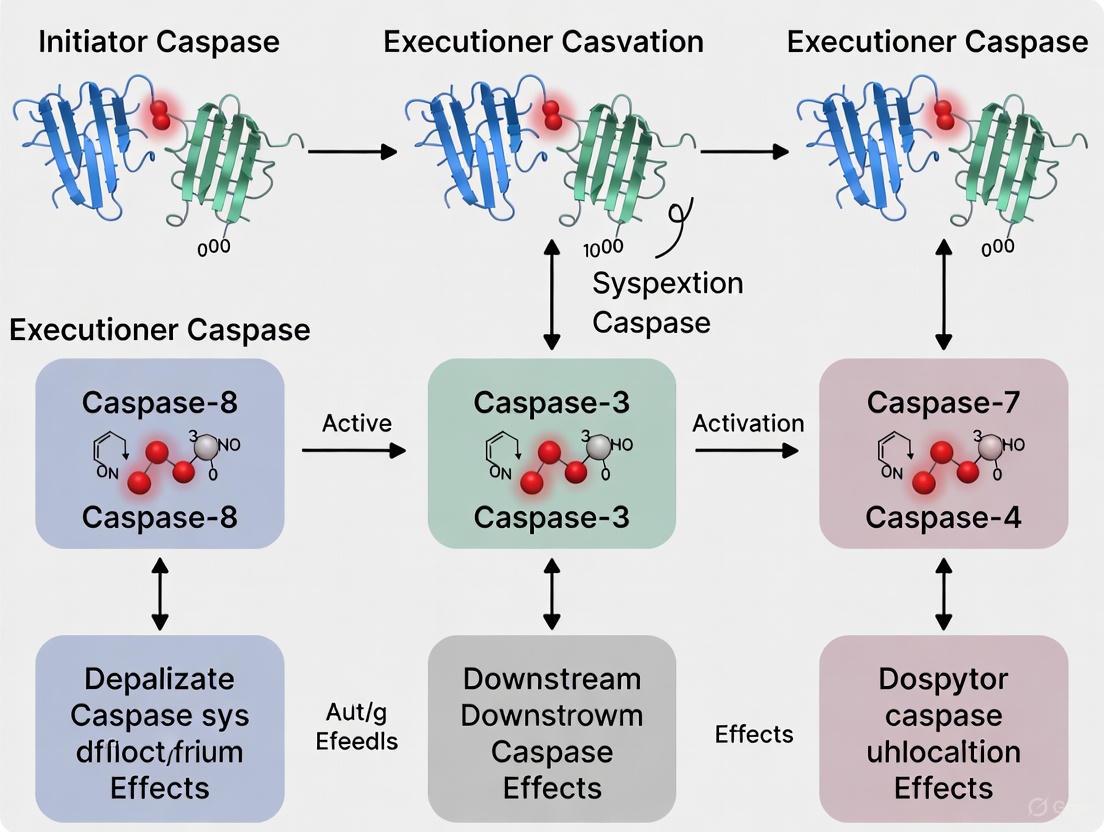

The classification of caspases into initiator, executioner, and inflammatory categories provides a foundational framework for understanding the caspase activation cascade and its functional consequences in both health and disease [4] [2]. This hierarchical organization allows for the precise regulation and amplification of death signals, culminating in the controlled demolition of cellular structures or the activation of inflammatory mediators [3] [5]. Growing understanding of caspase functions has established their importance as potential therapeutic targets for a wide spectrum of diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, autoimmune conditions, and infectious diseases [6] [7].

Caspase Classification and Molecular Structure

Caspases are synthesized as inactive zymogens (pro-caspases) that require proteolytic activation for their function [3] [4]. These zymogens consist of three primary domains: an amino-terminal pro-domain, a large catalytic subunit (~20 kDa), and a small catalytic subunit (~10 kDa) [6]. The pro-domain varies significantly among caspase types and contains critical protein-protein interaction motifs that determine how each caspase is activated and recruited into signaling complexes [3] [2].

Table: Caspase Classification by Structure and Function

| Caspase Type | Members | Pro-domain Feature | Activation Mechanism | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initiator | Caspase-2, -8, -9, -10 [4] | Long pro-domain with CARD or DED [3] | Dimerization-induced autoactivation [3] | Initiate apoptosis; signal amplification [5] |

| Executioner | Caspase-3, -6, -7 [4] | Short pro-domain (<30 amino acids) [5] | Cleavage by initiator caspases [3] | Cleave cellular substrates; execute cell death [5] |

| Inflammatory | Caspase-1, -4, -5, -11, -12 [4] [6] | Long pro-domain with CARD [7] | Inflammasome-mediated autoactivation [6] | Process cytokines; drive pyroptosis [6] |

The molecular structure of caspases directly correlates with their activation mechanisms and functional roles. Initiator caspases (caspase-2, -8, -9, -10) and inflammatory caspases contain long pro-domains featuring protein interaction motifs—either a caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD) or death effector domains (DED) [3] [2]. These domains facilitate recruitment and activation in multiprotein complexes through homotypic interactions [6]. In contrast, executioner caspases (caspase-3, -6, -7) possess only short pro-domains and depend on cleavage by initiator caspases for their activation [5].

The following diagram illustrates the structural organization of caspase zymogens and their activation mechanisms:

Caspase Structure and Activation Mechanisms

Caspase Activation Cascades and Signaling Pathways

Apoptotic Caspase Activation

Apoptosis, a non-inflammatory form of programmed cell death, proceeds through two principal pathways: the extrinsic (death receptor) pathway and the intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathway [3] [1]. Both pathways converge on the activation of executioner caspases that orchestrate the controlled demolition of cellular components [5].

The extrinsic pathway initiates when extracellular death ligands (e.g., FasL, TRAIL) bind to cell surface death receptors, leading to the formation of the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) [3]. The DISC recruits and activates initiator caspase-8 (and caspase-10 in humans) through dimerization mediated by death effector domains (DED) [3] [5]. In certain cell types (designated Type I), caspase-8 directly activates executioner caspases; in others (Type II), it connects to the intrinsic pathway through cleavage of the BH3-only protein Bid to tBid, which induces mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) [5].

The intrinsic pathway activates in response to diverse intracellular stresses including DNA damage, oxidative stress, and growth factor deprivation [3]. These stimuli trigger MOMP, resulting in cytochrome c release from mitochondria [3]. Cytochrome c binds to Apoptotic Protease-Activating Factor 1 (APAF-1), promoting formation of the heptameric apoptosome complex [3] [1]. The apoptosome recruits and activates initiator caspase-9 through CARD-CARD interactions, initiating a caspase cascade that leads to cell death [3].

Once activated, initiator caspases cleave and activate the executioner caspases-3, -6, and -7 [5]. These executioners then cleave hundreds of cellular substrates, resulting in the characteristic morphological changes of apoptosis, including chromatin condensation, DNA fragmentation, membrane blebbing, and formation of apoptotic bodies [5] [1]. Importantly, active executioner caspases can enhance MOMP and activate initiator caspases, forming a positive feedback loop that ensures rapid and complete activation of the apoptotic program [5].

The following diagram illustrates the major caspase activation pathways in apoptosis and pyroptosis:

Caspase Activation Pathways in Cell Death

Inflammatory Caspase Activation

Inflammatory caspases (caspase-1, -4, -5, -11, -12) primarily function in innate immune responses and drive inflammatory forms of cell death, particularly pyroptosis [6] [4]. These caspases are activated through macromolecular complexes known as inflammasomes, which form in response to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [6] [2].

The canonical inflammasome pathway involves caspase-1 activation through sensors such as NLRP3, NLRC4, AIM2, or Pyrin [6]. These sensors oligomerize upon ligand binding and recruit the adapter protein ASC, which then recruits and activates caspase-1 through CARD-CARD interactions [6] [2]. Active caspase-1 processes the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 into their mature, bioactive forms and cleaves gasdermin D (GSDMD) [6]. The N-terminal fragment of GSDMD oligomerizes to form pores in the plasma membrane, leading to pyroptosis—a lytic, inflammatory cell death [6] [1].

The non-canonical inflammasome pathway involves caspase-4 and -5 in humans and caspase-11 in mice, which directly recognize intracellular lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Gram-negative bacteria [6] [2]. This recognition leads to autocatalytic activation and subsequent cleavage of GSDMD, inducing pyroptosis independently of caspase-1 [6]. Additionally, non-canonical caspases can promote NLRP3-dependent caspase-1 activation through potassium efflux resulting from GSDMD pore formation [6].

Experimental Methodologies for Caspase Research

Key Research Reagents and Tools

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Caspase Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caspase Inhibitors | Z-VAD-FMK (pan-caspase) [7], Ac-YVAD-CHO (caspase-1) [7], Ac-DEVD-CHO (caspase-3) [7], Q-VD-OPh (broad-spectrum) [7] | Inhibit caspase activity; determine caspase-specific functions | Q-VD-OPh shows enhanced permeability and reduced toxicity compared to earlier inhibitors [7] |

| Activity Assays | Fluorogenic substrates (e.g., DEVD-AFC for caspase-3) [7], FRET-based caspase sensors [5] | Measure caspase activation kinetics and specificity | FRET sensors enable live-cell imaging of caspase activation dynamics [5] |

| Genetic Models | Caspase knockout mice [3], RNAi/CRISPR-mediated knockdown [1] | Determine physiological functions of specific caspases | Caspase-9 and Apaf-1 knockouts show brain development defects [3] |

| Detection Antibodies | Anti-cleaved caspase-3, anti-active caspase-1, anti-GSDMD [6] [5] | Detect caspase activation and substrate cleavage | Essential for immunohistochemistry and Western blot analysis |

| Cell Death Inducers | Staurosporine (intrinsic pathway) [3], Anti-Fas antibodies (extrinsic pathway) [6], LPS (pyroptosis) [6] | Activate specific cell death pathways | Determine pathway specificity and caspase involvement |

Core Methodological Approaches

Structural Biology Techniques: X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy have been instrumental in elucidating the atomic structures of caspases and their activation complexes, including the apoptosome and inflammasome [2]. These approaches reveal how caspases interact with their substrates and regulatory proteins, providing insights for targeted drug development [2].

Live-Cell Imaging and FRET Sensors: Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)-based caspase biosensors allow real-time monitoring of caspase activation kinetics in living cells [5]. These sensors have revealed that once initiated, executioner caspase activation peaks within 15 minutes, demonstrating the rapid, all-or-none nature of apoptotic commitment [5].

Genetic Manipulation Approaches: Gene targeting in mice has been essential for defining the physiological functions of individual caspases [3]. For example, caspase-9-deficient mice exhibit severe brain developmental defects due to reduced apoptosis, while caspase-8 deficiency is embryonic lethal due to impaired endothelial development [3].

The following diagram outlines a generalized experimental workflow for studying caspase functions:

Experimental Workflow for Caspase Research

Therapeutic Implications and Clinical Translation

Caspases represent promising therapeutic targets for a wide spectrum of diseases characterized by dysregulated cell death and inflammation [7]. In neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, excessive caspase activation contributes to neuronal loss, suggesting that caspase inhibitors might protect against disease progression [4] [7]. Conversely, in cancer, insufficient apoptosis allows tumor survival, suggesting that caspase activators or IAP antagonists could restore cell death sensitivity [4] [7].

The development of caspase-targeted therapies has faced significant challenges, particularly regarding specificity, efficacy, and toxicity [7]. Early peptide-based inhibitors such as Z-VAD-FMK demonstrated poor pharmacokinetics and off-target effects [7]. Second-generation inhibitors including IDN-6556 (emricasan) and VX-740 (pralnacasan) showed promise in clinical trials for liver diseases and rheumatoid arthritis, respectively, but development was halted due to toxicity concerns or inadequate efficacy [7].

Recent advances have identified novel therapeutic opportunities, particularly for inflammatory caspases. Caspase-4/5 inhibitors are being explored for inflammatory bowel disease, hidradenitis suppurativa, and sepsis, as these caspases are uniquely positioned in epithelial and endothelial inflammation [8]. Structural biology approaches have enabled the development of allosteric inhibitors with improved specificity and potency profiles [8].

Emerging research has also revealed that cells can survive transient executioner caspase activation, a phenomenon termed "survival from executioner caspase activation" (SECA) [5]. This survival mechanism has implications for cancer recurrence and tissue regeneration, suggesting more nuanced therapeutic approaches may be needed [5].

The classification of caspases into initiator, executioner, and inflammatory categories provides a fundamental framework for understanding their roles in cell death and inflammation. While this classification system has proven valuable, emerging research reveals substantial crosstalk and multifunctionality between caspase family members, challenging rigid categorical boundaries [2] [9]. The hierarchical caspase activation cascade ensures precise regulation of life-and-death decisions, with executioner caspases serving as the ultimate effectors of apoptotic demolition.

Future research directions include elucidating the structural basis for caspase substrate specificity, understanding context-dependent caspase functions in different cell types, and developing more sophisticated therapeutic strategies that target specific caspases in particular pathological contexts. As understanding of caspase biology continues to evolve, so too will opportunities for therapeutic intervention in the numerous diseases characterized by dysregulated cell death.

Caspases, a family of cysteine-dependent aspartate-specific proteases, function as central regulators of programmed cell death (PCD), inflammation, and innate immunity [1] [10]. These enzymes are synthesized as inactive precursors known as zymogens (or procaspases) that require proteolytic activation to gain their full catalytic function [11] [5]. The structural mechanisms maintaining this latency and the subsequent activation processes represent critical control points in cellular fate decisions, with profound implications for health and disease. Within the context of caspase cascade activation and executioner functions, understanding procaspase structure provides the foundational knowledge required to decipher how cells regulate life-and-death decisions. For drug development professionals, these structural insights offer attractive therapeutic targets for conditions ranging from cancer and neurodegenerative disorders to autoimmune and inflammatory diseases [1] [12]. This review synthesizes current structural knowledge of procaspase zymogens, focusing on the molecular determinants of latency and the domain rearrangements that unleash catalytic potential, thereby framing these insights within the broader landscape of caspase cascade research.

Caspase Classification and Domain Architecture

Caspases are historically categorized based on their primary functions in apoptosis (initiators and executioners) and inflammation, though increasing evidence reveals significant functional overlap [2]. Table 1 summarizes the classification, domain architecture, and activation features of human caspases.

Table 1: Human Caspase Classification and Domain Organization

| Caspase | Primary Classification | Pro-Domain Type | Activation Cleavage Sites | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caspase-1 | Inflammatory | CARD | Multiple aspartic sites | Pyroptosis, IL-1β/IL-18 maturation [11] [10] |

| Caspase-2 | Apoptotic Initiator | CARD | Inter-subunit linker | Cell cycle, DNA damage response, apoptosis [1] |

| Caspase-3 | Apoptotic Executioner | Short (∼30 aa) | Inter-subunit linker | Apoptosis execution, PARP cleavage, substrate proteolysis [5] |

| Caspase-4 | Inflammatory | CARD | Multiple aspartic sites | Non-canonical pyroptosis, GSDMD cleavage [2] |

| Caspase-5 | Inflammatory | CARD | Multiple aspartic sites | Non-canonical pyroptosis, GSDMD cleavage [2] |

| Caspase-6 | Apoptotic Executioner | Short (∼30 aa) | Inter-subunit linker | Apoptosis, lamin cleavage [1] |

| Caspase-7 | Apoptotic Executioner | Short (∼30 aa) | Inter-subunit linker | Apoptosis execution, PARP cleavage [5] |

| Caspase-8 | Apoptotic Initiator | DED | Inter-subunit linker | Extrinsic apoptosis, necroptosis regulation [1] [2] |

| Caspase-9 | Apoptotic Initiator | CARD | Inter-subunit linker | Intrinsic apoptosis, apoptosome formation [1] |

| Caspase-10 | Apoptotic Initiator | DED | Inter-subunit linker | Extrinsic apoptosis [1] |

All caspase zymogens share a conserved tripartite structure consisting of an N-terminal pro-domain, a large catalytic subunit (p20), and a small catalytic subunit (p10) [10] [5]. The pro-domain type represents a key differentiating feature: initiator and inflammatory caspases possess long pro-domains containing protein-protein interaction motifs such as the Caspase Activation and Recruitment Domain (CARD) or Death Effector Domain (DED) that facilitate recruitment to activation platforms [10]. In contrast, executioner caspases typically contain short pro-domains (less than 30 amino acids) without recognizable interaction motifs [5]. The catalytic domain, composed of the large and small subunits, adopts a caspase-hemoglobinase fold that forms the protease core [10].

Figure 1: Domain Architecture of Procaspase Zymogens. Initiator and inflammatory caspases feature long pro-domains (CARD) for recruitment to activation platforms, while executioner caspases have short pro-domains. Both share conserved large (p20) and small (p10) catalytic subunits.

Structural Basis of Zymogen Latency

The latent state of procaspases is maintained through specific structural constraints that prevent unauthorized proteolytic activity. Structural studies have revealed that procaspases exist as stable, inactive monomers or dimers, with their active sites incompletely formed [11]. The catalytic domain of all caspases consists of large and small catalytic subunits that form a caspase-hemoglobinase fold, characterized by a central β-sheet core surrounded by α-helices [10]. In the zymogen state, flexible loops and the inter-domain linker maintain the enzyme in an inactive conformation.

Key to maintaining latency is the arrangement of active site loops. The L1, L2, L3, and L4 loops surrounding the active site adopt orientations that preclude efficient substrate binding and catalysis [11]. Particularly important is the L2 loop (residues 314-316 in caspase-1), which in procaspase-1 occupies the active site cleft, effectively blocking substrate access [11]. This autoinhibitory configuration is stabilized by specific intramolecular interactions that must be disrupted during activation. The crystal structure of the procaspase-1 zymogen domain (solved at 2.05 Å resolution) revealed that although the isolated domain is monomeric in solution, it forms dimers in crystals, providing insight into the first autoproteolytic events during activation by oligomerization [11] [13].

Table 2: Structural Features Maintaining Zymogen Latency in Characterized Procaspases

| Procaspase | Quaternary Structure | Key Latency Features | Activation Trigger |

|---|---|---|---|

| Procaspase-1 | Monomeric (solution) | L2 loop blocks active site; incomplete active site formation | Inflammasome oligomerization [11] |

| Procaspase-7 | Dimeric | Inactive conformation with disordered active site loops | Cleavage by initiator caspases [11] |

| Procaspase-9 | Monomeric | Inactive conformation requiring apoptosome binding | Apoptosome-mediated dimerization [1] |

| DRONC (Drosophila caspase-9 ortholog) | Monomeric | CARD domain inhibits catalytic activity | Dimerization on activation platforms [11] |

For executioner caspases like procaspase-3 and procaspase-7, the zymogens exist as pre-formed dimers but remain catalytically incompetent due to the conformation of the inter-domain linker and active site loops [5]. Proteolytic processing at specific aspartic acid residues within the linker region triggers conformational changes that reorganize the active site into a catalytically competent state. The structural basis for this latency-activation switch varies among caspase subfamilies, reflecting their specialized roles in distinct cell death pathways.

Molecular Mechanisms of Procaspase Activation

Oligomerization-Induced Activation

Initiator and inflammatory caspases undergo activation through induced proximity and oligomerization on specific activation platforms. For inflammatory caspase-1, this occurs through inflammasome formation, where pattern recognition receptors (such as NLRP1 or NLRP3) recruit the adaptor protein ASC and procaspase-1 via CARD-CARD interactions [2]. This recruitment leads to procaspase-1 oligomerization, which facilitates auto-proteolytic cleavage at specific aspartic acid residues [11] [10].

The crystal structure of procaspase-1's zymogen domain revealed critical insights into this process. Although monomeric in solution, the protein formed dimers in crystals, with the loop arrangements in these dimers providing insight into the first autoproteolytic events [11]. Unlike other caspases, autoproteolysis at the second cleavage site (Asp316 in caspase-1) is necessary for conversion to a stable dimer in solution [11] [13]. This dimer stabilization is concurrent with a 130-fold increase in kcat, representing the sole contributing kinetic factor to an activated and efficient inflammatory mediator [11].

Figure 2: Procaspase Activation Pathway. Procaspase zymogens are recruited to activation platforms (1), where oligomerization (2) induces autoproteolytic cleavage (3), generating active caspases that cleave cellular substrates (4).

Proteolytic Activation by Upstream Caspases

Executioner caspases (caspase-3, -6, and -7) are primarily activated through proteolytic cleavage by upstream initiator caspases [5]. These executioner procaspases exist as pre-formed dimers in their zymogen state, with cleavage at specific inter-domain linkers triggering conformational changes that activate the enzyme. For example, initiator caspase-8 (activated by death receptors) or caspase-9 (activated by the apoptosome) cleaves executioner procaspase-3 at specific aspartate residues, resulting in rearrangement of the active site loops into a catalytically competent conformation [5].

This activation mechanism creates a proteolytic cascade that amplifies the initial apoptotic signal, ensuring rapid and efficient dismantling of the cell during apoptosis. Once activated, executioner caspases can process additional procaspase molecules, creating a positive feedback loop that ensures complete commitment to the cell death program [5].

Non-lethal Caspase Activation in Cellular Remodeling

Beyond their roles in cell death, caspases can be activated in sublethal contexts to participate in cellular remodeling and differentiation [14] [5]. In Drosophila olfactory receptor neurons, for example, the executioner caspase Drice is maintained in an inactive proform proximal to cell membrane proteins, including the cell adhesion molecule Fasciclin 3 (Fas3) [14]. This localization restricts caspase activation to specific subcellular compartments, enabling participation in neuronal functional modulation without triggering cell death [14].

This non-lethal activation requires precise regulation of caspase activity through subcellular compartmentalization, interaction with regulatory proteins, and controlled degradation. The identification of caspase-proximal proteins through techniques like TurboID has revealed how caspases are sequestered and regulated in specific cellular locations to facilitate their non-apoptotic functions [14].

Quantitative Analysis of Caspase Activation Parameters

Biochemical studies of caspase activation have yielded quantitative parameters that characterize the transition from zymogen to active enzyme. Table 3 summarizes key kinetic and structural parameters for representative caspases.

Table 3: Quantitative Parameters of Caspase Zymogen Activation

| Caspase | Activation Method | Key Cleavage Sites | Rate Enhancement (kcat increase) | Quaternary Structure Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caspase-1 | Inflammasome oligomerization | Multiple sites including Asp316 | 130-fold after dimer stabilization [11] | Monomer → Stable dimer [11] |

| Caspase-3 | Cleavage by initiator caspases | Asp175, Asp9, etc. | Not specified in results | Dimer → Active dimer [5] |

| Caspase-7 | Cleavage by initiator caspases | Multiple inter-subunit sites | Not specified in results | Dimer → Active dimer [11] |

| Caspase-9 | Apoptosome-mediated dimerization | Not specified in results | Not specified in results | Monomer → Active dimer [1] |

The activation of caspase zymogens involves significant structural rearrangements that can be quantified through biophysical methods. For procaspase-1, removal of the caspase recruitment domain (CARD) and crystallization of the zymogen domain allowed for detailed structural analysis of the latency mechanism [11]. The structure revealed that proteolysis at Asp316 is necessary for formation of a stable dimer in solution, with dimer stabilization directly correlating with the dramatic increase in catalytic efficiency [11] [13].

Experimental Approaches for Studying Procaspase Structure and Function

Structural Biology Methods

X-ray Crystallography: The crystal structure of procaspase-1's zymogen domain (without its CARD domain) was solved to 2.05 Å resolution, providing atomic-level insight into inflammatory caspase autoactivation [11]. This approach revealed how loop arrangements in the dimer facilitate the first autoproteolytic events during activation by oligomerization.

Cryo-Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM): While not directly applied to procaspases in the available search results, cryo-EM has been used to study related cell death machinery, such as the structure of the apoptotic scramblase Xkr4 [15]. This technique is increasingly valuable for studying large caspase activation complexes like inflammasomes and apoptosomes.

Biochemical and Biophysical Assays

Size Exclusion Chromatography with Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS): This method was used to analyze procaspase-1 C285A processing and dimerization, demonstrating that autoproteolysis at the second cleavage site is necessary for conversion to a stable dimer in solution [11].

TurboID Proximity Labeling: A proximity-dependent biotinylation technique used to identify proteins proximal to executioner caspases in Drosophila brains [14]. This method revealed that the executioner caspase Drice is proximal to cell membrane proteins, including Fasciclin 3, while in its inactive proform.

Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) Sensors: These sensors enable live monitoring of executioner caspase activation during apoptosis, revealing that once initiated, activation peaks within 15 minutes [5].

Molecular Biology and Protein Engineering

Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Used to validate the functional importance of specific residues in caspase activation. For example, mutation of the catalytic cysteine (C285A) in caspase-1 facilitated structural studies of the zymogen without auto-processing [11].

Recombinant Protein Expression in E. coli: Wild-type human caspase-1 (residues 104-404) and various constructs were cloned into pRSET T7 expression vectors and expressed in BL21Star(DE3) cells for purification and structural studies [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Procaspase Studies

| Reagent / Method | Application | Key Features / Function |

|---|---|---|

| pRSET T7 Expression Vector | Recombinant caspase expression | N-terminal Unizyme tag for purification [11] |

| BL21Star(DE3) E. coli cells | Protein expression | Co-transformed with pRARE2 for rare codon supplementation [11] |

| HisTrap HP Column | Protein purification | Immobilized metal affinity chromatography for His-tagged proteins [11] |

| SEC-MALS (Size Exclusion with MALS) | Oligomerization state analysis | Determines molecular weight and oligomeric state in solution [11] |

| TurboID | Proximity-dependent labeling | Identifies proteins proximal to caspases in living cells [14] |

| FRET-based caspase sensors | Live-cell activity monitoring | Real-time detection of caspase activation kinetics [5] |

| Caspase inhibitors (Z-VAD, VX-765) | Functional validation | Pan-caspase inhibitors to confirm caspase-dependent phenotypes [12] |

Implications for Therapeutic Development

The structural insights into procaspase latency and activation have significant implications for therapeutic development across multiple disease areas. Excessive caspase-1 activity drives pathologies in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases such as septic shock, inflammatory bowel disease, familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and gout [11]. Similarly, dysregulated apoptotic caspases contribute to cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and ischemic injuries [1] [12].

Understanding the precise molecular mechanisms of zymogen activation has revealed novel targeting strategies beyond active site inhibition. Allosteric inhibitors that prevent procaspase activation by stabilizing the latent conformation represent a promising therapeutic approach [11] [12]. For example, the structural insights from procaspase-1 revealed critical elements of secondary structure that explain why a dimeric protein is favored after proteolysis, suggesting opportunities for dimerization inhibitors [11].

The development of specific caspase inhibitors faces challenges due to conservation among caspase family members, but the unique features of zymogen structures and activation mechanisms offer potential for achieving selectivity. As our structural understanding of procaspases continues to advance, so too will opportunities for therapeutic intervention in the numerous diseases characterized by dysregulated caspase activity.

The structural biology of procaspase zymogens has revealed sophisticated molecular mechanisms that maintain caspase latency and control their activation. Through specific domain architectures, autoinhibitory conformations, and regulated oligomerization, cells precisely control the potent proteolytic activity of caspases until needed. The insights gained from crystal structures, biochemical analyses, and innovative experimental approaches have not only advanced our fundamental understanding of caspase biology but have also opened new avenues for therapeutic intervention in diseases characterized by dysregulated cell death and inflammation. As research continues to elucidate the subtleties of procaspase regulation across different biological contexts and caspase family members, our ability to precisely modulate these pathways for therapeutic benefit will continue to grow, ultimately contributing to improved treatments for cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, autoimmune conditions, and infectious diseases.

Caspases, or cysteine-dependent aspartate-specific proteases, are central regulators of programmed cell death and inflammation [2]. Their activation triggers and executes critical biological processes, most notably apoptosis. A fundamental principle in caspase biology is the existence of a two-tiered cascade where upstream initiator caspases activate downstream executioner caspases [16]. However, these two groups employ fundamentally distinct molecular mechanisms for their activation: initiator caspases are activated through induced proximity-induced dimerization, while executioner caspases require proteolytic cleavage between their large and small subunits [17] [16]. This mechanistic dichotomy represents a sophisticated evolutionary adaptation that ensures precise control over life-and-death cellular decisions. Understanding these distinct activation pathways is essential for researchers investigating basic cell biology mechanisms and drug development professionals targeting caspase pathways in diseases such as cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and inflammatory conditions [1].

Molecular Mechanisms of Initiator Caspase Activation

The Induced Proximity Model

Initiator caspases (caspase-2, -8, -9, and -10 in humans) exist within healthy cells as inactive monomers [17] [16]. Unlike executioner caspases, their activation does not require proteolytic cleavage. Instead, they are activated through dimerization brought about by their recruitment into specific signaling complexes [17]. This process is described by the "induced proximity" model, which posits that bringing multiple caspase monomers into close proximity drives their activation [17] [16].

The key structural feature enabling this mechanism is the presence of long prodomains in initiator caspases (approximately 150-200 amino acids) that contain protein-protein interaction domains such as death effector domains (DEDs) in caspases-8 and -10, or caspase activation and recruitment domains (CARDs) in caspases-9 and -2 [17] [2] [5]. These domains allow initiator caspases to interact with adapter proteins that dimerize or oligomerize, thereby bringing caspase monomers into close proximity [17].

Table 1: Key Features of Initiator Caspases in Humans

| Caspase | Prodomain Type | Primary Activation Complex | Main Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caspase-8 | Two DEDs | Death-Inducing Signaling Complex (DISC) | Extrinsic Apoptosis |

| Caspase-9 | CARD | Apoptosome | Intrinsic Apoptosis |

| Caspase-10 | Two DEDs | Death-Inducing Signaling Complex (DISC) | Extrinsic Apoptosis |

| Caspase-2 | CARD | PIDDosome | DNA Damage Response |

Structural Basis of Initiator Caspase Activation

The structural rearrangement during initiator caspase activation is remarkable. In the monomeric state, the catalytic site is not properly formed. Dimerization induces conformational changes that create a functional active site [17]. While cleavage between the large and small subunits is not required for the initial activation step, it does occur subsequently and serves to stabilize the active dimer,

particularly for caspases-2 and -8 [17]. This stabilization is biologically crucial, as non-cleavable mutants of caspase-8 can be activated by dimerization but do not efficiently promote apoptosis [17]. An exception to this rule is caspase-9, whose activity is not stabilized by cleavage but is instead regulated by the apoptosome complex [17].

Figure 1: Initiator Caspase Activation via Induced Proximity. Monomeric initiator caspases are recruited to adapter protein complexes, leading to dimerization and activation through induced proximity.

Molecular Mechanisms of Executioner Caspase Activation

Proteolytic Cleavage as the Activation Trigger

In stark contrast to initiator caspases, executioner caspases (caspase-3, -6, and -7 in humans) preexist in the cytosol of healthy cells as inactive dimers [17] [16] [5]. These zymogens contain only short prodomains (less than 30 amino acids) that lack protein-protein interaction domains [5]. Their activation requires proteolytic cleavage at specific aspartic acid residues located between the large and small subunits [17] [5].

In the inactive procaspase dimer, the catalytic dyads are not properly positioned to access the target aspartate in substrate proteins [17]. Cleavage of the inter-subunit linker allows dramatic conformational changes that snap the two active sites into their functional configuration [17]. Specifically, cleavage liberates the ends of the cleaved linkers, enabling them to interact with the opposite chain and stabilize a structure where the loops comprising the specificity pockets can assume their active positions [17].

Structural Consequences of Cleavage

The structural transformation during executioner caspase activation has been visualized through crystallographic studies of caspase-7 [17]. In the inactive procaspase-7 dimer, the central region is occupied by the linker segments between the large and small subunits. After cleavage, this space becomes available, allowing the "elbow" of the specificity loop to extend into the center of the dimer, thereby forming two functional active sites [17]. Once activated, executioner caspases can process hundreds or thousands of cellular substrates, leading to the characteristic morphological changes of apoptosis, including chromatin condensation, DNA fragmentation, and membrane blebbing [5].

Table 2: Key Features of Executioner Caspases in Humans

| Caspase | Prodomain Length | Primary Activator | Key Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caspase-3 | Short (<30 aa) | Caspase-8, -9, -10 | PARP, ICAD, USP48 |

| Caspase-7 | Short (<30 aa) | Caspase-8, -9, -10 | PARP, Gasdermins |

| Caspase-6 | Short (<30 aa) | Caspase-3, -7 | Lamin A/C |

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Key Experimental Evidence

The distinct activation mechanisms of initiator and executioner caspases have been demonstrated through multiple experimental approaches:

For initiator caspases, recombinant caspase-2, -8, or -9 that lack prodomains are enzymatically inactive when isolated. However, when salt conditions are altered to promote aggregation and dimerization, caspase activity rapidly appears even when cleavage sites between large and small subunits have been mutated [17]. This provides direct evidence that dimerization, not cleavage, drives initial activation. When the aggregating conditions are reversed, cleaved active dimers remain active, whereas uncleavable mutants lose activity, demonstrating the role of cleavage in stabilization rather than activation [17].

For executioner caspases, structural biology approaches have revealed the conformational changes associated with activation. Comparison of procaspase-7 structures before and after cleavage shows how cleavage permits the formation of the functional active site [17]. Biochemical studies demonstrate that executioner caspases can be activated in vitro by initiator caspases or other proteases like granzyme B, which is released by cytotoxic lymphocytes to eliminate virally infected or tumor cells [17].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Initiator Caspase Dimerization Assay

Purpose: To demonstrate that initiator caspase activation occurs through dimerization rather than proteolytic cleavage.

Methodology:

- Protein Preparation: Express and purify recombinant initiator caspases (e.g., caspase-8) with truncated prodomains in Escherichia coli.

- Mutagenesis: Generate cleavage-site mutants by site-directed mutagenesis, replacing the aspartic acid residue at the cleavage site with alanine or glutamic acid.

- Low-Salt Conditions: Maintain caspases in low-salt buffer (e.g., 50 mM NaCl) to prevent spontaneous aggregation.

- Induced Dimerization: Increase salt concentration to 300-500 mM NaCl to promote caspase aggregation and dimerization.

- Activity Measurement: Monitor caspase activity using fluorogenic substrates (e.g., Ac-IETD-AFC for caspase-8) at excitation/emission wavelengths of 400/505 nm.

- Reversal Test: Gradually decrease salt concentration while continuously monitoring enzyme activity.

- Analysis: Compare activity profiles of wild-type and cleavage-site mutant caspases under different salt conditions.

Expected Results: Both wild-type and cleavage-site mutant caspases show rapid activity increases upon salt-induced dimerization. When salt concentration is decreased, wild-type caspases maintain activity while mutant caspases rapidly lose activity, demonstrating that cleavage stabilizes but does not initiate activity [17].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Executioner Caspase Cleavage Assay

Purpose: To demonstrate that executioner caspase activation requires proteolytic cleavage between large and small subunits.

Methodology:

- Protein Preparation: Express and purify executioner procaspases (e.g., procaspase-3) as inactive dimers.

- Activation Conditions: Incubate procaspases with:

- Initiator caspases (e.g., active caspase-8 or -9)

- Granzyme B (as a positive control)

- Buffer alone (negative control)

- Cleavage Analysis: Monitor cleavage by:

- Western blotting using antibodies against the large and small subunits

- Size-exclusion chromatography to detect conformational changes

- Activity Assay: Measure caspase activity using fluorogenic substrates (e.g., Ac-DEVD-AFC for caspase-3).

- Mutagenesis: Test cleavage-site mutants to confirm the specificity of activation.

Expected Results: Only cleaved executioner caspases show significant proteolytic activity. Cleavage-site mutants remain inactive even when incubated with initiator caspases, confirming that inter-domain cleavage is essential for activation [17] [5].

Figure 2: The Caspase Activation Cascade. Death stimuli trigger the formation of adapter complexes that dimerize initiator caspases, which then cleave and activate executioner caspases, leading to apoptosis.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Caspase Activation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorogenic Substrates | Ac-DEVD-AFC (Caspase-3), Ac-IETD-AFC (Caspase-8), Ac-LEHD-AFC (Caspase-9) | Activity measurement | Emit fluorescence upon cleavage; specific tetrapeptide recognition sequences |

| Active Recombinant Caspases | Active caspase-3, -8, -9 | In vitro cleavage assays; positive controls | Highly purified; validated activity |

| Caspase Inhibitors | Z-VAD-FMK (pan-caspase), Ac-DEVD-CHO (caspase-3 specific) | Specificity controls; therapeutic exploration | Irreversible (FMK) or reversible (CHO) inhibition mechanisms |

| Antibodies | Anti-cleaved caspase-3, anti-caspase-8, anti-PARP | Western blotting; immunohistochemistry | Detect activation-specific cleavage events |

| Cell Death Inducers | Staurosporine, Fas Ligand, TNF-α | Apoptosis induction in cell culture | Activate intrinsic or extrinsic pathways |

| Caspase Expression Plasmids | Wild-type and mutant constructs | Structure-function studies | Enable site-directed mutagenesis of cleavage sites |

Discussion: Biological Significance and Therapeutic Implications

The evolutionary conservation of distinct activation mechanisms for initiator and executioner caspases highlights their fundamental importance in maintaining precise control over programmed cell death. The induced proximity mechanism for initiator caspases allows the cell to integrate multiple death signals through various adapter proteins, providing signaling specificity [17] [16]. Meanwhile, the cleavage-based activation of executioner caspases creates a crucial amplification step, where a single active initiator caspase can activate numerous executioner caspases, ensuring rapid and complete commitment to cell death once the decision is made [5].

Recent research has revealed surprising complexity in these activation paradigms. For example, caspase-8 demonstrates remarkable functional plasticity, serving as a molecular switch between apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis depending on cellular context [1]. Additionally, non-apoptotic roles for caspases have been identified in processes such as neuronal function modification, where restricted, subcellular activation of executioner caspases occurs without triggering cell death [14]. In Drosophila olfactory receptor neurons, the executioner caspase Drice is proximal to cell membrane proteins like Fasciclin 3, which facilitates non-lethal caspase activation that modulates neuronal function rather than causing death [14].

From a therapeutic perspective, the distinct activation mechanisms offer unique opportunities for drug development. Targeting initiator caspase dimerization interfaces or their interactions with adapter proteins could provide greater specificity than targeting the conserved active sites of executioner caspases [1] [2]. Furthermore, understanding context-dependent caspase activation is crucial for developing treatments for cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and inflammatory disorders where caspase regulation is disrupted [1] [18] [2]. For instance, in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), caspase-3 specifically cleaves ubiquitin-specific peptidase 48 (USP48) during drug-induced apoptosis, suggesting potential therapeutic strategies targeting this interaction [18] [19].

The continued elucidation of caspase activation mechanisms thus represents a critical frontier at the intersection of basic cell biology and therapeutic development, with implications for treating a wide spectrum of human diseases.

Apoptosis, a form of programmed cell death (PCD), is a crucial process in multicellular organisms for eliminating unwanted or damaged cells. This genetically controlled cell suicide mechanism is characterized by distinct morphological changes, including cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, DNA fragmentation, and formation of apoptotic bodies that are rapidly phagocytosed without inducing inflammation [20]. Apoptosis occurs through the activation of a cascade of cysteine proteases known as caspases (cysteine-dependent aspartate-specific proteases), which cleave their substrates after aspartic acid residues [2] [21]. These enzymes serve as the central executioners of apoptotic cell death, systematically dismantling cellular structures through the cleavage of key protein substrates [1] [5].

The caspase family is broadly categorized into initiator and executioner caspases based on their position in the proteolytic cascade. Initiator caspases (caspase-2, -8, -9, -10) contain long pro-domains that enable them to respond to proximal apoptotic signals, while executioner caspases (caspase-3, -6, -7) possess short pro-domains and function downstream to directly mediate the terminal events of cell death [2] [5]. Activation of initiator caspases occurs through induced proximity at specific signaling platforms, whereas executioner caspases are activated through proteolytic cleavage by initiator caspases [22]. Once activated, executioner caspases cleave hundreds of cellular substrates, including structural proteins, DNA repair enzymes, and cell cycle regulators, leading to the characteristic biochemical and morphological hallmarks of apoptosis [5].

Table 1: Major Caspases in Apoptotic Pathways

| Caspase | Type | Primary Pathway | Key Functions and Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caspase-8 | Initiator | Extrinsic | Initiates extrinsic pathway; cleaves Bid, caspase-3, -6, -7 [1] [5] |

| Caspase-9 | Initiator | Intrinsic | Activated by apoptosome; cleaves caspase-3, -7 [2] [5] |

| Caspase-10 | Initiator | Extrinsic | Death receptor-mediated apoptosis; regulates caspase-8 [1] |

| Caspase-2 | Initiator | Intrinsic | DNA damage response; cleaves Bid [1] |

| Caspase-3 | Executioner | Both | Primary executioner; cleaves PARP, lamins, ICAD; activates GSDME [1] [2] [5] |

| Caspase-7 | Executioner | Both | Cleaves PARP; suppresses pyroptosis via GSDMD cleavage [1] [5] |

| Caspase-6 | Executioner | Both | Activates caspase-8; lamin cleavage [1] [5] |

This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of the three principal apoptotic pathways—extrinsic, intrinsic, and granzyme B—focusing on their molecular mechanisms, regulatory networks, and experimental approaches for studying caspase cascade activation and executioner functions.

The Extrinsic Apoptotic Pathway

Molecular Mechanism

The extrinsic pathway, also known as the death receptor pathway, is initiated by the binding of extracellular death ligands to their corresponding cell surface death receptors. This pathway is primarily involved in eliminating cells in response to external signals, particularly in immune regulation and host defense [2]. Key death receptors include TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1), Fas (CD95), and TRAIL receptors (DR4 and DR5), which belong to the TNF receptor superfamily [20].

Upon ligand binding, death receptors undergo trimerization and conformational changes that enable the recruitment of adapter proteins through homotypic interactions between death domains (DD). For instance, Fas-associated death domain (FADD) is recruited to the activated Fas receptor, forming the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) [2] [5]. The DISC then recruits initiator caspases, primarily caspase-8 and caspase-10, through interactions between death effector domains (DED), leading to their dimerization and activation [22] [2]. Once activated, caspase-8 directly cleaves and activates executioner caspases-3, -6, and -7, initiating the apoptotic execution phase [5].

Diagram 1: Extrinsic Apoptotic Pathway Activation via Death Receptors

Regulatory Networks and Crosstalk

The extrinsic pathway exhibits sophisticated regulatory mechanisms that determine cellular fate. A key regulatory molecule is cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein (c-FLIP), which structurally resembles caspase-8 but lacks proteolytic activity. c-FLIP competes with caspase-8 for binding to FADD at the DISC, thereby modulating caspase-8 activation [20]. Additionally, caspase-8-mediated cleavage of the Bcl-2 family protein Bid generates truncated Bid (tBid), which translocates to mitochondria and activates the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, creating a crucial amplification loop [5] [23].

The classification of cells into type I and type II based on their apoptotic signaling reflects this crosstalk. In type I cells, robust caspase-8 activation at the DISC directly activates executioner caspases sufficiently to induce apoptosis without mitochondrial amplification. In contrast, type II cells require caspase-8-mediated Bid cleavage and mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) to fully activate the apoptotic cascade [22] [5]. This classification has important implications for cancer therapy resistance, as many cancer cells evolve toward type II signaling to evade death receptor-mediated apoptosis.

Experimental Analysis of Extrinsic Pathway

Live-cell imaging using FRET-based reporters has revealed the dynamic regulation of caspase activation in the extrinsic pathway. Specifically, caspase-8 activity is detected during the prolonged delay that precedes MOMP and effector caspase activation [22]. Experimental perturbation studies demonstrate that XIAP and proteasome-dependent degradation of effector caspases serve as critical restraints during this pre-MOMP period [22].

Table 2: Key Experiments in Extrinsic Pathway Analysis

| Experimental Approach | Methodology | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Live-cell caspase activity monitoring | FRET-based reporters (IC-RP for initiator, EC-RP for effector caspases) | Initiator caspases active during variable delay before MOMP; effector activation is rapid (<15 min) [22] |

| DISC immunoprecipitation | Co-immunoprecipitation of FADD, caspase-8 from death receptor complexes | Identified composition and regulation of primary signaling complex [2] [5] |

| Type I/II cell classification | Caspase inhibition, Bid knockout, mitochondrial function assessment | Revealed mitochondrial amplification requirement in type II cells [22] [5] |

| Mathematical modeling | ODE-based models of caspase activation dynamics | Identified XIAP and proteasomal degradation as key regulators delaying effector activation [22] [23] |

The Intrinsic Apoptotic Pathway

Molecular Mechanism

The intrinsic pathway, also known as the mitochondrial pathway, is initiated in response to intracellular stress signals, including DNA damage, oxidative stress, growth factor withdrawal, and endoplasmic reticulum stress [23] [20]. These signals converge on mitochondria, leading to mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), which represents a commitment point to cell death [23].

The Bcl-2 protein family serves as the central regulator of MOMP, comprising three functional subgroups: (1) Pro-apoptotic effector proteins (Bax and Bak) that directly mediate MOMP; (2) Anti-apoptotic proteins (Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1) that inhibit Bax/Bak activation; and (3) BH3-only proteins (Bid, Bim, Puma, Bad, Noxa) that sense cellular stress and regulate the balance between pro- and anti-apoptotic members [23]. In response to stress signals, activator BH3-only proteins (Bim, Bid, Puma) directly engage and activate Bax and Bak, while sensitizer BH3-only proteins (Bad, Noxa) neutralize anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins [23].

Upon activation, Bax and Bak undergo conformational changes and oligomerize to form pores in the mitochondrial outer membrane, leading to the release of cytochrome c and other pro-apoptotic factors from the mitochondrial intermembrane space [23] [20]. Cytochrome c then binds to Apaf-1 in the cytosol, promoting ATP-dependent oligomerization into a wheel-like signaling platform known as the apoptosome. The apoptosome recruits and activates initiator caspase-9, which subsequently cleaves and activates executioner caspases-3 and -7 [2] [20].

Diagram 2: Intrinsic Apoptotic Pathway via Mitochondrial Signaling

Regulatory Networks and Amplification Loops

The intrinsic pathway features multiple regulatory checkpoints and amplification mechanisms that ensure precise control over cell fate decisions. Anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins preserve mitochondrial integrity by sequestering activator BH3-only proteins and directly inhibiting Bax/Bak activation [23]. The balance between pro- and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members functions as a rheostat for cellular susceptibility to apoptosis.

Following MOMP, additional mitochondrial proteins are released that modulate apoptosis. Second mitochondria-derived activator of caspases (Smac/DIABLO) neutralizes inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs), particularly XIAP, which would otherwise inhibit caspase-3, -7, and -9 activity [23] [20]. Simultaneously, Omi/HtrA2 serine protease also antagonizes IAPs and promotes apoptosis. This coordinated release of pro-apoptotic factors ensures efficient caspase activation following MOMP.

A critical positive feedback loop exists between executioner caspases and the intrinsic pathway. Active caspase-3 cleaves various substrates, including the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2, converting it into a pro-apoptotic fragment that further promotes MOMP [5]. Additionally, caspase-3-mediated activation of caspase-6 can generate additional caspase-8 through a feedback loop, further amplifying the apoptotic signal [22].

Experimental Analysis of Intrinsic Pathway

Mathematical modeling of Bcl-2 family interactions has revealed that MOMP operates as a rapid, switch-like response that is robust to variability in protein expression levels [23]. This switch-like behavior arises from the complex interplay of activation and inhibition within the Bcl-2 protein network.

Single-cell analysis using IMS-RP (intermembrane space reporter protein) has demonstrated that MOMP is completed within less than 5 minutes, though stimulus-specific differences in kinetics become apparent at second-scale resolution [22]. The release of mitochondrial proteins occurs as a sudden, all-or-none event at the single-cell level, explaining the commitment point characteristic of intrinsic apoptosis.

BH3 profiling represents a functional experimental approach to assess mitochondrial priming and apoptotic susceptibility by measuring the response of mitochondria to specific BH3-only peptides [23]. This technique has proven valuable for predicting cancer cell responses to chemotherapeutic agents and for identifying dependencies on specific anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members for survival.

The Granzyme B Pathway

Molecular Mechanism

The granzyme B pathway represents a crucial mechanism for immune-mediated elimination of virus-infected and cancerous cells by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and natural killer (NK) cells. This pathway bridges innate and adaptive immunity by enabling immune cells to directly induce apoptosis in target cells [2]. Granzyme B is a serine protease stored in the granules of cytotoxic lymphocytes and is delivered to target cells through perforin-mediated pores or receptor-mediated endocytosis.

Upon delivery into the target cell cytoplasm, granzyme B cleaves and activates multiple apoptotic substrates, functioning similarly to both initiator and executioner caspases. Granzyme B directly cleaves caspase-3, -6, -7, -8, and -10, bypassing the need for upstream signaling complexes and rapidly initiating the apoptotic cascade [2]. Additionally, granzyme B cleaves the BH3-only protein Bid to generate truncated Bid (tBid), which translocates to mitochondria and induces MOMP, thereby engaging the intrinsic pathway for signal amplification [5].

Beyond caspase activation, granzyme B directly cleaves key apoptotic substrates, including ICAD (inhibitor of caspase-activated DNase), leading to DNA fragmentation, and PARP [poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase], disrupting DNA repair mechanisms [2]. This multi-pronged approach ensures rapid and efficient destruction of target cells before viral replication or defensive responses can occur.

Regulatory Networks and Immune Surveillance

The granzyme B pathway operates under tight regulatory control to prevent inappropriate immune-mediated cell killing. Serpins (serine protease inhibitors), particularly proteinase inhibitor 9 (PI-9) in humans, inhibit granzyme B activity and protect cytotoxic lymphocytes from self-destruction [2]. The expression of PI-9 in certain tissues may provide protection against immune-mediated damage, while its upregulation in cancer cells represents a mechanism of immune evasion.

The efficiency of granzyme B-mediated apoptosis is influenced by the expression of IAP family proteins in target cells. XIAP directly inhibits caspase-3 and -7, potentially resisting granzyme B-induced apoptosis [5]. However, granzyme B can circumvent this inhibition through multiple mechanisms, including direct caspase processing and Bid-mediated MOMP leading to Smac/DIABLO release, which neutralizes XIAP [2] [20].

Experimental Analysis of Granzyme B Pathway

Studies utilizing granzyme B-deficient mice have revealed its essential role in controlling viral infections and tumor surveillance. These models demonstrate that while other granzymes (particularly granzyme A) can partially compensate, granzyme B is uniquely efficient at inducing rapid apoptosis in target cells [2].

In vitro reconstitution assays using purified granzyme B and perforin have been instrumental for identifying direct substrates and deciphering the hierarchy of apoptotic events. These studies confirmed that granzyme B can directly process executioner caspases-3 and -7, as well as initiate mitochondrial amplification through Bid cleavage [2].

Live-cell imaging of granzyme B-mediated killing has revealed remarkably rapid kinetics, with target cells displaying apoptotic morphology within minutes of exposure to activated cytotoxic lymphocytes. This rapid induction reflects the direct activation of executioner mechanisms without the need for complex upstream signaling events [2].

Execution Phase: Caspase Activation and Substrate Cleavage

Molecular Mechanisms of Caspase Activation

The execution phase of apoptosis represents the final common pathway where activated executioner caspases systematically dismantle cellular structures. Executioner caspases-3, -6, and -7 exist as inactive dimers (zymogens) in healthy cells, requiring proteolytic cleavage by initiator caspases for activation [5]. Cleavage occurs at specific aspartic acid residues, separating the pro-domain and generating separate large and small subunits that reassemble to form the active enzyme [21] [5].

Once activated, executioner caspases exhibit a >100-fold increase in proteolytic activity and function as the primary effectors of apoptotic cell death [22]. Caspase-3 serves as the major executioner caspase, with caspase-7 sharing overlapping substrates and functions. Caspase-6 has distinct substrates and additionally functions in feedback amplification by processing caspase-8 [1] [5]. The activation of executioner caspases follows an "all-or-none" pattern at the single-cell level, with activation peaking within 15 minutes of initiation [5].

Apoptotic Substrate Cleavage and Morphological Changes

Executioner caspases target hundreds of cellular proteins for limited proteolysis, resulting in the characteristic morphological and biochemical hallmarks of apoptosis [5]. Key substrate categories include:

- Nuclear proteins: Cleavage of ICAD (inhibitor of caspase-activated DNase) releases CAD, which executes DNA fragmentation between nucleosomes, creating the characteristic DNA ladder. Lamin cleavage disrupts the nuclear envelope, contributing to nuclear shrinkage and fragmentation [5] [20].

- Cytoskeletal proteins: Cleavage of cytoskeletal components (actin, fodrin, gelsolin) and regulatory proteins (FAK, p21-activated kinase 2) mediates membrane blebbing and cell shrinkage [5].

- DNA repair enzymes: Cleavage of PARP prevents DNA repair while conserving cellular ATP for the apoptotic process [21] [5].

- Cell cycle regulators: Cleavage of various cell cycle proteins ensures termination of proliferative signaling [5].

- Anti-apoptotic proteins: Cleavage of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and IAPs converts them into pro-apoptotic fragments, creating positive feedback loops that amplify the death signal [5].

Table 3: Key Executioner Caspase Substrates and Functions

| Substrate | Caspase | Functional Consequence of Cleavage |

|---|---|---|

| PARP | Caspase-3, -7 | Inactivates DNA repair; conserves ATP [21] [5] |

| ICAD | Caspase-3 | Releases CAD nuclease for DNA fragmentation [5] |

| Lamin A/C | Caspase-6 | Nuclear envelope disintegration [5] |

| GSDME | Caspase-3 | Generates N-terminal fragment that induces pyroptosis [1] [2] |

| Bcl-2 | Caspase-3 | Converts anti-apoptotic protein to pro-apoptotic form [5] |

| FAK | Caspase-3, -6 | Disrupts focal adhesions; contributes to cell detachment [5] |

| Rho-associated kinase | Caspase-3 | Regulates membrane blebbing [5] |

Alternative Cell Death Outcomes

Emerging evidence indicates that executioner caspase activation does not invariably lead to cell death. Cells can survive sublethal caspase activation through a process called anastasis, particularly in response to transient or low-intensity stress [5]. Survival from executioner caspase activation (SECA) has been documented in both physiological contexts (e.g., developmental processes) and pathological conditions (e.g., cancer therapy resistance) [5].

The consequences of SECA depend on cellular context and stress intensity. In some scenarios, SECA contributes to tissue regeneration and recovery, while in others it promotes genomic instability and oncogenesis due to incomplete DNA fragmentation and repair [5]. Cancer cells that survive caspase activation often exhibit enhanced stem cell-like properties and increased aggressiveness, representing a potential mechanism of therapy resistance [5].

Research Methods and Applications

Experimental Approaches for Apoptosis Detection

Advanced methodologies have been developed to detect and quantify apoptosis in real-time, providing insights into the dynamics of caspase activation and execution. Key technologies include:

- Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) reporters: Engineered constructs containing caspase cleavage sites between fluorophore pairs that exhibit FRET signal loss upon cleavage, enabling real-time monitoring of caspase activity in live cells [22].

- Annexin V staining: Detects phosphatidylserine externalization on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, an early event in apoptosis [24].

- Mitochondrial membrane potential sensors: Dyes like JC-1 and TMRM that detect the collapse of mitochondrial membrane potential associated with MOMP [22].

- IAP-based reporters: Constructs that monitor IAP activity or Smac release from mitochondria [22].

- High-throughput flow cytometry: Enables multiparameter analysis of apoptotic markers across large cell populations with single-cell resolution [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Apoptosis Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Caspase Activity Assays | Fluorogenic substrates (DEVD-AMC for caspase-3, IETD-AFC for caspase-8) | Quantitative measurement of specific caspase activities in cell lysates [21] [22] |

| Apoptosis Detection Kits | Annexin V-FITC/PI staining kits | Differentiation of live, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic cells by flow cytometry [24] |

| Live-Cell Reporters | FRET-based caspase reporters (EC-RP, IC-RP), IMS-RP | Real-time monitoring of caspase activation and MOMP in living cells [22] |

| Caspase Inhibitors | Z-VAD-FMK (pan-caspase), Z-DEVD-FMK (caspase-3) | Pharmacological inhibition to establish caspase-dependence of cell death [21] |

| Antibodies for Western Blot | Anti-cleaved caspase-3, anti-PARP, anti-cytochrome c | Detection of specific proteolytic events and protein relocalization [22] [24] |

| BH3 Profiling Peptides | BIM, BAD, HRK-derived peptides | Functional assessment of mitochondrial priming and Bcl-2 family dependencies [23] |

Therapeutic Applications and Drug Development

The understanding of apoptotic pathways has enabled the development of targeted therapies, particularly for cancer treatment. Several therapeutic classes have emerged:

- BH3 mimetics: Small molecules (e.g., venetoclax/ABT-199) that specifically inhibit anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins, promoting MOMP and apoptosis in cancer cells [23] [25].

- IAP antagonists: Compounds that mimic Smac/DIABLO to neutralize IAP-mediated caspase inhibition, sensitizing cells to apoptosis [23] [25].

- Death receptor agonists: Monoclonal antibodies that activate death receptors (e.g., TRAIL receptor agonists) to directly engage the extrinsic pathway [25].

- Caspase activators: Experimental compounds that directly promote caspase activation, though clinical development has proven challenging due to toxicity concerns [25].

The global apoptosis assay market, valued at USD 6.5 billion in 2024 and projected to reach USD 14.6 billion by 2034, reflects the growing importance of apoptosis research in drug discovery and development [24]. Technological advances including high-content screening, 3D cell culture compatibility, and AI-powered image analysis are enhancing the precision and throughput of apoptosis detection in both research and clinical applications [24].

Diagram 3: Apoptosis Research Applications and Therapeutic Development

The extrinsic, intrinsic, and granzyme B apoptotic pathways represent sophisticated molecular cascades that converge on caspase activation to execute programmed cell death. While each pathway initiates through distinct mechanisms—death receptor engagement, mitochondrial stress signaling, or immune-mediated protease delivery—they share common executioner caspases that systematically dismantle cellular structures through limited proteolysis of key substrates.

Recent advances in live-cell imaging, mathematical modeling, and single-cell analysis have revealed the dynamic regulation and systems-level properties of apoptotic signaling networks. The discovery of alternative cell fate outcomes, including survival from executioner caspase activation and non-apoptotic caspase functions, has added complexity to our understanding of these pathways. Furthermore, the crosstalk between apoptotic and other forms of regulated cell death, such as pyroptosis and necroptosis, highlights the integrated nature of cell death control [1] [2].

Ongoing research continues to elucidate the structural basis of caspase activation and substrate recognition, the systems-level properties emerging from protein interaction networks, and the therapeutic potential of modulating apoptotic pathways for cancer and other diseases. As detection technologies advance and our molecular understanding deepens, the manipulation of apoptotic pathways represents a promising frontier for targeted therapeutic interventions across a spectrum of human diseases.

Executioner caspases-3, -6, and -7 function as terminal effectors in the caspase cascade, responsible for the precise proteolytic cleavage of hundreds of cellular substrates to orchestrate apoptotic cell death. Their coordinated activity leads to the characteristic morphological changes of apoptosis, including DNA fragmentation, membrane blebbing, and formation of apoptotic bodies. Recent research has expanded their known substrate repertoire and revealed context-specific functions beyond core apoptosis. This whitepaper comprehensively details the validated substrate profiles, cleavage motifs, experimental methodologies for identification, and functional consequences of executioner caspase activity, providing a foundational resource for researchers investigating caspase biology and therapeutic applications.

Within the hierarchical framework of apoptotic signaling, executioner caspases-3, -6, and -7 occupy the terminal position, responsible for implementing the controlled demolition of cellular structures. Caspases (cysteine-aspartic proteases) are a family of proteases that cleave their substrates after specific aspartic acid residues within short tetrapeptide motifs [4]. The apoptotic caspase cascade is initiated by upstream signaling events that activate initiator caspases (such as caspase-8, -9, and -10), which subsequently cleave and activate the downstream executioner caspases-3, -6, and -7 [3] [5]. This amplification mechanism ensures rapid and irreversible commitment to cell death once the threshold for activation is surpassed.

Executioner caspases are synthesized as inactive zymogens (pro-caspases) that exist as dimers in healthy cells. They contain a short pro-domain (less than 30 amino acids) compared to the long pro-domains of initiator caspases [5]. Activation occurs through cleavage by initiator caspases at specific aspartic residues between the large and small subunits, resulting in conformational changes that form the active enzyme, typically a heterotetramer composed of two large and two small subunits [21] [3]. Once activated, a single executioner caspase can cleave and activate other executioner caspases, establishing an accelerated feedback loop that ensures complete activation [3].

The functional repertoire of executioner caspases extends beyond their classical role in apoptosis. Emerging evidence indicates that sublethal activation of these enzymes participates in diverse physiological processes including cellular differentiation, synaptic plasticity, and innate immunity [26]. This whitepaper focuses specifically on their canonical function as executioners of cell death, framing their substrate repertoire within the context of caspase cascade activation and the systematic dismantling of cellular architecture.

Substrate Repertoire of Executioner Caspases

Executioner caspases recognize and cleave a diverse array of cellular proteins, with current estimates exceeding 600 identified substrates [4]. The specific cleavage events disrupt key cellular processes and structures, leading to the orderly disintegration characteristic of apoptosis. While caspase-3 serves as the primary executioner with the broadest substrate profile, caspases-6 and -7 contribute complementary and unique cleavage activities.

Table 1: Key Validated Substrates of Executioner Caspases

| Substrate Category | Specific Substrate | Cleaving Caspase | Functional Consequence of Cleavage |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Repair & Maintenance | PARP (Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase) | Caspase-3, -7 [27] | Inactivates DNA repair, conserves cellular ATP [27] |

| ICAD/DFF45 (DNA fragmentation factor) | Caspase-3 [5] | Releases CAD nuclease, enables DNA fragmentation [5] | |

| Nuclear Integrity | Lamin A | Caspase-6 [27] | Disassembles nuclear lamina [27] |

| Cytoskeletal Organization | α-Fodrin | Caspase-3 [28] | Disrupts membrane cytoskeleton, contributes to blebbing [28] |

| Gelsolin | Caspase-3 [5] | Generates active fragment that severs actin, aiding disassembly [5] | |

| Apoptosis Regulation | Beclin 1 | Caspase-3 [29] | Inactivates autophagy, promotes apoptosis [29] |

| USP48 (Ubiquitin-specific peptidase 48) | Caspase-3 [18] | Enhances drug-induced apoptosis in AML [18] | |

| Inflammatory Signaling | GSDME (Gasdermin E) | Caspase-3 [27] | Can induce secondary pyroptosis [27] |

| GSDMD (Gasdermin D) | Caspase-3, -7 [27] | Non-canonical cleavage at D87 suppresses pyroptosis [27] |

Caspase-3: The Primary Executioner

Caspase-3 possesses the most extensive substrate profile among the executioners and is often considered the primary effector of apoptotic morphology. Its activation is characterized by an "all-or-none" pattern, typically peaking within 15 minutes of initiation [5]. Caspase-3 recognizes the DEVD (Asp-Glu-Val-Asp) tetrapeptide motif, which forms the basis for many activity assays and inhibitors [28].

Key cleavage events mediated by caspase-3 include:

- Inactivation of DNA repair machinery through cleavage of PARP, preventing futile repair attempts and conserving cellular ATP for the apoptotic process [27].

- Activation of DNA fragmentation by cleaving ICAD/DFF45, which releases the CAD nuclease to execute internucleosomal DNA cleavage [5].

- Disruption of cytoskeletal integrity through cleavage of α-fodrin, gelsolin, and other structural proteins, leading to membrane blebbing and loss of cell shape [28] [5].

- Regulation of cross-talk between cell death pathways by cleaving Beclin 1 to inhibit autophagy and promote apoptosis [29], and processing gasdermin proteins which can modulate pyroptosis [27].

A recent 2025 study identified USP48 as a novel caspase-3 substrate, demonstrating cleavage at a specific DEQD motif (611-614) during drug-induced apoptosis in Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML). This cleavage generates an N-terminal fragment that is destabilized, and knockdown experiments confirmed that USP48 inhibition promotes apoptosis and enhances chemotherapy efficacy, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target [18].

Caspase-7: A Collaborator with Distinct Roles

Caspase-7 shares significant structural homology with caspase-3 and overlaps in some substrate specificities, including PARP cleavage [27]. However, emerging evidence reveals non-redundant functions. Caspase-7 plays a particularly important role in suppressing pyroptosis through non-canonical cleavage of GSDMD at Asp87, which prevents its oligomerization and pore-forming activity [27]. This illustrates how executioner caspases can actively inhibit alternative cell death pathways to ensure an immunologically silent apoptotic demise.

Caspase-6: The Laminase and Beyond

Caspase-6 exhibits a more restricted substrate profile but performs critical specialized functions. It is historically known as the primary laminase, responsible for cleaving nuclear lamin proteins to facilitate nuclear envelope disassembly [27]. Beyond this role, caspase-6 can activate caspase-8, creating a feedback amplification loop that enhances the apoptotic signal [27]. It also regulates GSDMB-mediated pyroptosis, further highlighting the complex interplay between different cell death modalities [27].

Table 2: Characteristic Cleavage Motifs and Activation Patterns

| Executioner Caspase | Characteristic Recognition Motif | Activation Mechanism | Temporal Activation Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caspase-3 | DEVD [28] | Cleavage by initiator caspases (8, 9, 10) [3] | Rapid, "all-or-none" peak within 15 min [5] |

| Caspase-6 | VEHD [27] | Cleavage by caspase-3, -7, -8 [27] | Delayed relative to caspase-3 [27] |

| Caspase-7 | DEVD [27] | Cleavage by initiator caspases [3] | Simultaneous or slightly delayed versus caspase-3 [5] |

Experimental Methodologies for Analyzing Executioner Caspase Activity

A diverse toolkit of biochemical, imaging, and proteomic approaches enables researchers to detect executioner caspase activation and identify novel substrates. The selection of appropriate methodologies depends on the specific research question, ranging from single-cell temporal dynamics to system-wide substrate identification.

Fluorescence-Based Detection Methods

Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) sensors provide real-time, single-cell resolution monitoring of caspase activation dynamics. These genetically encoded reporters typically consist of two fluorescent proteins (e.g., CFP and YFP) linked by a short peptide containing the caspase-specific cleavage motif (e.g., DEVD for caspase-3). Upon cleavage, the separation of the fluorophores alters the FRET efficiency, allowing quantitative kinetic analysis [5]. This approach revealed that executioner caspase activation, once initiated, follows a rapid, switch-like behavior peaking within 15 minutes [5].

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) imaging offers a label-free alternative for monitoring caspase activity. In one described platform, a chimeric GST:DEVD:EGFP fusion protein is immobilized on a chip surface. Caspase-3 cleavage at the DEVD sequence alters the surface properties, detectable as a change in the refractive index, allowing sensitive and quantitative activity measurements [28].

Proteomic Approaches for Substrate Identification

Systematic identification of caspase substrates requires proteomic strategies:

- Western Blot Analysis: The foundational method for detecting substrate cleavage by observing characteristic proteolytic fragments and their dependence on caspase activity, often using pan-caspase inhibitors like Z-VAD-fmk or caspase-specific inhibitors [29].