Cytochrome c Release in Intrinsic Apoptosis: Molecular Mechanisms, Regulation, and Therapeutic Implications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the cytochrome c release mechanism within the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Cytochrome c Release in Intrinsic Apoptosis: Molecular Mechanisms, Regulation, and Therapeutic Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the cytochrome c release mechanism within the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It synthesizes current understanding of the molecular events initiating mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), the pivotal role of BCL-2 family proteins, and the consequences of cytochrome c release for apoptosome formation and caspase activation. The scope extends to methodological approaches for detecting and quantifying cytochrome c release, addresses common challenges in experimental models, and explores the pathway's validation across different biological systems. Finally, the discussion covers the significant implications for targeting this pathway in cancer therapy and other human diseases, providing a foundational resource for both basic research and translational applications.

The Fundamental Biology of Cytochrome c Release: From Basic Localization to Apoptotic Trigger

Cytochrome c is a multifunctional mitochondrial hemoprotein that plays two quintessential roles in cellular fate: it is indispensable for electron transport in aerobic respiration and acts as a pivotal signaling molecule in the initiation of intrinsic apoptosis. This whitepaper delves into the sophisticated mechanisms governing cytochrome c's release from mitochondria, a decisive event in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. We examine the protein's structural domains that facilitate its dual functions, the key regulatory checkpoints involving BCL-2 family proteins, and the subsequent formation of the apoptosome complex. Furthermore, this review synthesizes current experimental methodologies for studying cytochrome c release and discusses the therapeutic implications of targeting this pathway in drug development, particularly for cancer therapeutics where apoptotic evasion is a hallmark of disease.

Cytochrome c (Cyt c) is a nuclear-encoded, mitochondrial hemoprotein that serves as a critical nexus in cellular homeostasis, embodying a dual function that is as paradoxical as it is essential [1]. Its primary and historical role is as an essential electron carrier in the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC), where it shuttles electrons between Complex III (coenzyme Q-cytochrome c reductase) and Complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) to facilitate oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production [2] [3] [4]. This function is vital for life, as evidenced by the embryonic lethality in cytochrome c-knockout mice during mid-gestation, coinciding with the metabolic shift to aerobic energy production [1].

In a contrasting role, cytochrome c is a central signaling molecule in programmed cell death. In response to diverse cellular stress signals, cytochrome c is released from the mitochondrial intermembrane space into the cytosol, where it triggers the activation of the caspase cascade via apoptosome formation [5] [6] [7]. This process is indispensable for the elimination of damaged or superfluous cells, and its dysregulation is a hallmark of numerous diseases, including cancer and neurodegenerative disorders [5] [1]. This whitepaper will deconstruct the mechanisms of cytochrome c's release and apoptotic activity, framing it within the broader context of intrinsic pathway research.

Structural Determinants of Dual Functionality

The ability of cytochrome c to perform its two distinct roles is encoded in its highly conserved structure. It is a small (104 amino acids in mammals), water-soluble protein with a high isoelectric point (pI ~9.6), owing to its abundance of lysine residues [3] [1].

- Heme Group and Electron Transfer: The core of its function lies in the heme c group, a prosthetic group covalently attached to the protein backbone via thioether bonds with Cys14 and Cys17 [7] [1]. The heme iron is coordinated by His18 and Met80, which are critical for its redox activity [1]. This structure allows the iron to oscillate between ferrous (Fe²⁺) and ferric (Fe³⁺) states, facilitating single electron transfer [2] [4]. Key lysine residues (e.g., Lys8, Lys13, Lys27, Lys72, Lys86, Lys87) surrounding the solvent-exposed heme edge are essential for electrostatic interactions with its redox partners, cytochrome c1 (Complex III) and cytochrome c oxidase (Complex IV) [7].

- Apoptotic Signaling Interface: The same lysine-rich domain is also crucial for its apoptotic function. Structural studies, including cryo-electron microscopy, have revealed that specific cytochrome c residues (including Lys7, Lys25, Trp59, Glu62, Lys72, and Ile75) interact with Apoptotic Protease Activating Factor 1 (Apaf-1) [7]. The binding of cytochrome c to Apaf-1 is a critical step that relieves Apaf-1's autoinhibition, enabling apoptosome assembly. Notably, the K72A mutation in cytochrome c ablates its ability to activate Apaf-1 while preserving its electron transfer function, demonstrating a clear structural and functional segregation of its two roles [7].

Table 1: Key Structural Features of Cytochrome c and Their Functional Implications

| Structural Feature | Description | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|

| Heme c Group | Iron porphyrin cofactor; iron coordinated by His18 and Met80 [1] | Redox activity; electron shuttling between Complex III and IV [2] |

| CXXCH Motif | Highly conserved sequence (Cys14, Cys17, His18) [3] [7] | Covalent heme attachment via thioether bonds [7] |

| Lysine-Rich Patch | Cluster of positively charged residues (e.g., Lys8, Lys13, Lys72) [7] | Electrostatic docking with respiratory complexes and Apaf-1 [7] |

| Evolutionary Conservation | 34 of 104 amino acids are invariant across species [3] | Underpins essential, non-redundant functions in respiration and apoptosis [4] |

The Intrinsic Apoptotic Pathway: Cytochrome c Release as a Point of No Return

The intrinsic apoptotic pathway is initiated by internal cellular stressors, such as DNA damage, oxidative stress, or growth factor withdrawal. A key event in this pathway is the mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), which allows cytochrome c to escape into the cytosol.

Regulation by BCL-2 Family Proteins

The permeabilization of the mitochondrial outer membrane is tightly regulated by the BCL-2 protein family, which consists of both pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic members [8] [6].

- Pro-apoptotic Effectors: Proteins like BAX and BAK are the ultimate executioners of MOMP. In response to apoptotic signals, they undergo conformational activation, translocate to the mitochondria, and oligomerize to form pores in the outer mitochondrial membrane [8] [6]. Cells deficient in both Bax and Bak are highly resistant to intrinsic apoptotic stimuli and cytochrome c release [6].

- Anti-apoptotic Guardians: Proteins like Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL reside on the outer mitochondrial membrane and act to restrain BAX and BAK, thereby preventing MOMP and cytochrome c release [6]. Overexpression of Bcl-2/Bcl-xL confers resistance to apoptosis, as demonstrated in etoposide-treated Jurkat cell studies [6].

- Sensitizers and Activators: BH3-only proteins (e.g., BIM, BID, PUMA) act as sentinels for cellular damage. They can either directly activate BAX/BAK or neutralize the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins, thus tipping the balance towards apoptosis [8] [6].

Cardiolipin Peroxidation and Release

A critical preparatory step for cytochrome c release is its dissociation from the inner mitochondrial membrane. Cytochrome c is loosely associated with the inner membrane via electrostatic interactions with the phospholipid cardiolipin [5] [3]. During apoptosis induction, cytochrome c exhibits a peroxidase activity that catalyzes the oxidation of cardiolipin [5] [1]. Oxidation of cardiolipin reduces its negative charge and binding affinity for the positively charged cytochrome c, liberating the protein into the intermembrane space and facilitating its subsequent release through BAX/BAK pores [5] [1].

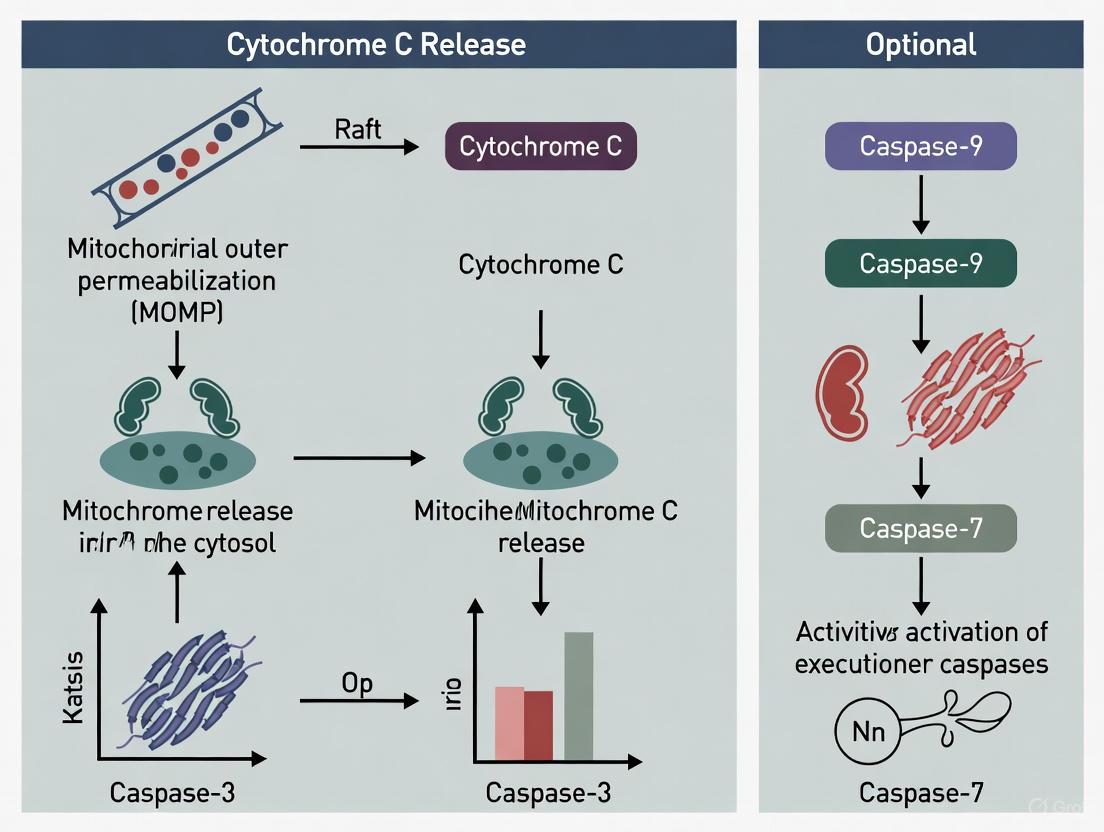

The following diagram illustrates the sequence of events in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, culminating in cytochrome c release and apoptosome-mediated caspase activation.

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Cytochrome c Release

Investigating the dynamics of cytochrome c release and its functional consequences requires a suite of well-established biochemical and cell biological techniques. The following section details key experimental protocols.

Subcellular Fractionation and Immunoblotting

This classic biochemical approach is used to directly monitor the translocation of cytochrome c from mitochondria to the cytosol.

- Workflow:

- Apoptosis Induction: Treat cells (e.g., Jurkat T-lymphocytes) with an intrinsic apoptotic stimulus such as etoposide (e.g., 10 μM) [6].

- Cell Permeabilization: Harvest cells and subject them to gentle, digitonin-based permeabilization. Digitonin selectively perforates the cholesterol-rich plasma membrane while leaving intracellular organelles, including mitochondria, intact [6].

- Fractionation: Centrifuge the permeabilized cell suspension. The supernatant (S) contains the cytosolic fraction, while the pellet (P) contains the heavy membrane fraction (enriched with mitochondria) [6].

- Western Blot Analysis: Resolve the proteins from both fractions by SDS-PAGE and perform immunoblotting using antibodies specific for cytochrome c. The appearance of cytochrome c in the cytosolic fraction is a definitive marker of its release. Controls should include markers for compartment purity, such as cytochrome c oxidase (mitochondria) and tubulin or lactate dehydrogenase (cytosol) [6].

Flow Cytometry for Apoptotic Phenotypes

While not a direct measure of cytochrome c, flow cytometry is used to quantify downstream apoptotic events that confirm the functional consequence of its release.

- Annexin V/Propidium Iodide (PI) Staining: This assay detects phosphatidylserine externalization (an early apoptotic event) and loss of plasma membrane integrity (a late apoptotic/necrotic event). Cells are stained with annexin V-FITC and PI, and analyzed by flow cytometry to distinguish live (annexin V⁻/PI⁻), early apoptotic (annexin V⁺/PI⁻), and late apoptotic/necrotic (annexin V⁺/PI⁺) populations [6] [9].

- Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (ΔΨm) Measurement: The fluorescent dye DiIC1(5) is a potentiometric probe that accumulates in polarized mitochondria. A collapse in ΔΨm, which often accompanies MOMP and cytochrome c release, results in a loss of fluorescence, detectable by flow cytometry [6].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Studying Cytochrome c in Apoptosis

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Etoposide | DNA-damaging chemotherapeutic agent; induces intrinsic apoptosis [6] | Standard stimulus for studying cytochrome c release in Jurkat cells [6] |

| Digitonin | Mild detergent for selective plasma membrane permeabilization [6] | Used in subcellular fractionation to isolate cytosolic contents [6] |

| Anti-Cytochrome c Antibody | Immunodetection of cytochrome c localization [6] | Western blotting of cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions [6] |

| BAX/BAK deficient cells | Genetic models to study necessity of effector proteins [6] | Demonstrates absolute requirement for MOMP and cytochrome c release [6] |

| Bcl-2/Bcl-xL overexpression | Genetic model of anti-apoptotic signaling [6] | Confirms inhibition of cytochrome c release and apoptosis resistance [6] |

| Caspase Inhibitors (e.g., z-VAD-fmk) | Pan-caspase inhibitor [8] | Used to dissect caspase-dependent and -independent aspects of cytochrome c-induced death [8] |

Yeast as a Model Organism

The baker's yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has proven to be a powerful tool for elucidating the conserved, core mechanisms of cytochrome c-mediated apoptosis.

- Protocol for Acetic Acid-Induced PCD: Stationary-phase yeast cells are resuspended in treatment medium at pH 3.0 and exposed to acetic acid (e.g., 140 mM) for 200 minutes [9]. Viability is assessed by colony-forming unit (CFU) counts.

- Readouts: In this model, cytochrome c release can be detected by immunoblotting of subcellular fractions. Associated events like reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, depletion of cytochrome c oxidase, and loss of ΔΨm can be measured polarographically and spectroscopically [9]. The use of yeast mutants (e.g., ρ⁰ strains lacking mitochondrial DNA) provides genetic evidence for the mitochondria-dependent nature of the process [9].

The experimental workflow for a comprehensive analysis integrating several of these techniques is outlined below.

Implications for Drug Development and Disease Therapeutics

The central role of cytochrome c release in apoptosis makes it an attractive target for therapeutic intervention, especially in oncology.

- Cancer and Apoptotic Evasion: Many cancers exhibit reduced levels of cytochrome c or impaired release mechanisms, contributing to apoptotic resistance and tumor survival [5]. For instance, lower cytochrome c levels in advanced glioma stages correlate with poorer prognosis [5]. Restoring cytochrome c function or sensitizing cells to its release is a key therapeutic strategy.

- Targeting Regulatory Nodes: Intense research focuses on developing BH3-mimetics, small molecules that inhibit anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins (like Bcl-2 itself or Bcl-xL) [7]. By neutralizing these guardians, BH3-mimetics promote BAX/BAK activation, MOMP, and cytochrome c release, thereby forcing cancerous cells into apoptosis. Drugs like venetoclax (targeting Bcl-2) are clinical validations of this approach.

- Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs): Phosphorylation, acetylation, and nitration of cytochrome c can fine-tune its functions, influencing both electron transport and apoptotic potency [5] [7] [1]. For example, phosphorylation at Tyr48 inhibits apoptosis, effectively turning cytochrome c into an anti-apoptotic switch [3]. Understanding these PTMs offers novel avenues for drug discovery, aiming to modulate cytochrome c's activity rather than just its expression.

Cytochrome c stands as a paradigm of biological efficiency, where a single protein integrates multiple cellular signals to govern the critical decision between life and death. Its dual role is not a contradiction but a sophisticated adaptation: it is the linchpin of aerobic energy production and the messenger of cellular suicide. The precise mechanism of its release from mitochondria, governed by the BCL-2 family and cardiolipin peroxidation, remains a focal point of intrinsic pathway research. Continued elucidation of the regulatory networks controlling cytochrome c, aided by advanced genetic models and detection technologies, holds immense promise for developing targeted therapies that can reinstate apoptotic programs in diseases defined by their absence, such as cancer, and protect vulnerable cells in degenerative conditions.

The BCL-2 protein family serves as the central arbiters of the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway, integrating diverse cellular stress signals to determine cell fate. The pivotal event controlled by this family is the mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), a decisive step that leads to the release of cytochrome c and other apoptogenic factors from the mitochondrial intermembrane space. Once cytochrome c is released into the cytosol, it triggers the formation of the apoptosome and the subsequent activation of caspase cascades that execute programmed cell death. The critical role of BCL-2 family interactions in regulating cytochrome c release places them at the heart of intrinsic apoptosis research, with profound implications for understanding cancer pathogenesis and developing targeted therapies.

The BCL-2 Family: Architects of Cellular Fate

Structural and Functional Classification

The BCL-2 family consists of evolutionarily conserved proteins that share Bcl-2 homology (BH) domains (BH1-BH4). These proteins are structurally characterized by a globular fold comprising a central hydrophobic α-helix surrounded by amphipathic α-helices, resembling the pore-forming domains of bacterial toxins [10] [11]. Based on their function and domain organization, family members are classified into three principal subgroups:

Table 1: Classification of Principal BCL-2 Family Proteins

| Subgroup | Representative Members | BH Domains | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-apoptotic | BCL-2, BCL-xL, BCL-w, MCL-1, A1 | BH1-BH4 | Promote cell survival by inhibiting pro-apoptotic members |

| Pro-apoptotic Effectors | BAX, BAK, BOK | BH1-BH3 | Direct mediators of MOMP |

| BH3-only Sensitizers | BIM, BID, PUMA, BAD, NOXA, BMF, HRK | BH3 only | Stress sensors that initiate or promote apoptosis |

The hydrophobic groove formed by the BH1-BH3 domains on the surface of anti-apoptotic proteins serves as the critical binding site for the BH3 α-helix of pro-apoptotic partners. This interaction is fundamental to the life-death balance maintained by the family [12] [11].

Anti-apoptotic Members: Guardians of Survival

Anti-apoptotic proteins such as BCL-2, BCL-xL, and MCL-1 function as crucial survival factors by preserving mitochondrial membrane integrity. They neutralize pro-apoptotic family members through direct binding, thereby preventing MOMP and cytochrome c release. Gene targeting studies reveal distinct but partially overlapping physiological roles: BCL-2 is essential for the survival of mature lymphocytes and kidney cells, BCL-xL for developing neurons and erythrocytes, and MCL-1 for early embryogenesis and hematopoietic progenitors [12].

Pro-apoptotic Effectors: Executioners of MOMP

BAX and BAK are the essential multidomain pro-apoptotic effectors required for mitochondrial permeabilization. Cells deficient in both BAX and BAK are profoundly resistant to diverse apoptotic stimuli, including the overexpression of BH3-only proteins [12]. In healthy cells, BAX resides predominantly in the cytosol as a monomer, while BAK is constitutively integrated into the mitochondrial membrane. Upon activation by BH3-only proteins, both undergo conformational changes, oligomerize, and form pores that facilitate cytochrome c release [12] [10].

BH3-only Proteins: Sentinels of Cellular Stress

The BH3-only proteins act as specialized sensors that become activated in response to specific intracellular damage signals. For instance, DNA damage induces p53-mediated transcriptional upregulation of PUMA and NOXA, while growth factor withdrawal leads to the activation of BAD [12]. Once activated, they promote apoptosis by binding to and neutralizing anti-apoptotic family members, and in some cases, by directly activating BAX and BAK [12] [13].

Molecular Mechanisms Governing Cytochrome c Release

The Pivotal Role of Cytochrome c

Cytochrome c is a nuclear-encoded hemoprotein normally confined to the mitochondrial intermembrane space, where it functions as an indispensable electron shuttle in the respiratory chain between Complex III and Complex IV [1] [14]. Its release into the cytosol represents a point of commitment in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Cytosolic cytochrome c binds to APAF-1, triggering apoptosome formation and the subsequent activation of caspase-9 and the executioner caspase-3 [14].

Mechanisms of Cytochrome c Mobilization and Release

The release of cytochrome c is a tightly regulated, multi-stage process:

- Mobilization from the Inner Membrane: A significant fraction of cytochrome c is electrostatically and hydrophobically bound to the phospholipid cardiolipin in the inner mitochondrial membrane. Detachment, or mobilization, is a prerequisite for its release. This can be facilitated by cardiolipin oxidation, which reduces its affinity for cytochrome c, or by increased cytosolic calcium levels, which weaken their electrostatic interaction [14].

- Translocation through the OMM: The permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane is controlled by BAX and BAK oligomers. The prevailing hypothesis suggests that these oligomers form a pore, the Mitochondrial Apoptosis-induced Channel (MAC), which allows for the diffusion of cytochrome c and other IMS proteins into the cytosol [12] [14]. This model is supported by the structural similarity of BCL-2 family proteins to bacterial pore-forming toxins and the ability of recombinant BAX to form cytochrome c-permeable pores in artificial liposomes [12].

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathway through which the BCL-2 family regulates cytochrome c release and apoptosis.

Experimental Approaches for Studying BCL-2 Family Interactions

Research into the BCL-2 family employs a multi-faceted methodological arsenal to decipher complex protein interactions and functional outcomes.

Structural Biology Techniques

X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy have been instrumental in elucidating the three-dimensional structures of multiple BCL-2 family members, including BCL-xL, BCL-2, BAX, and BID [11]. These studies revealed the conserved fold and the critical hydrophobic groove on anti-apoptotic proteins. Furthermore, structures of BCL-xL in complex with BH3 peptides have shown that the BH3 domain binds the groove as an amphipathic α-helix, providing a molecular blueprint for drug discovery efforts [11].

- Protocol Outline: Crystallography of BCL-2 Family Proteins

- Protein Expression & Purification: Recombinant human BCL-2 protein (e.g., BCL-xL) is expressed in E. coli and purified via affinity and size-exclusion chromatography.

- Crystallization: The protein is concentrated and subjected to sparse matrix screening to identify crystallization conditions, often using vapor diffusion methods.

- Data Collection & Structure Solution: X-ray diffraction data is collected at a synchrotron source. The structure is solved by molecular replacement using a known homologous structure.

- Complex Analysis: For co-crystals with BH3 peptides, the peptide is synthesized and soaked into crystals or co-crystallized with the protein.

Analyzing Protein Interactions and MOMP

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) are widely used to quantitatively measure the binding affinities (KD) between anti-apoptotic proteins and BH3 peptides or mimetics [12] [15]. To study the functional consequence of these interactions, researchers employ liposome-based assays to reconstitute MOMP in a defined system. Recombinant BAX/BAK is incubated with liposomes mimicking the mitochondrial outer membrane, and cytochrome c release is measured spectrophotometrically or by ELISA [12].

Cellular and Genetic Models

Gene-targeted mice deficient in specific BCL-2 family members have been pivotal in defining their non-redundant physiological functions. For example, bim^-/-^ mice accumulate excess lymphocytes and display resistance to specific apoptotic stimuli, while puma^-/-^ mice are resistant to DNA damage-induced apoptosis [12]. In cellular studies, BH3 profiling is a functional assay that measures mitochondrial priming by challenging permeabilized cells with synthetic BH3 peptides and monitoring membrane potential or cytochrome c release to predict apoptotic sensitivity [15].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Studying the BCL-2 Family

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant BCL-xL / BCL-2 Protein | Protein | Structural studies (X-ray, NMR) and in vitro binding assays (SPR, ITC). |

| BH3 Peptides (e.g., from BIM, BID) | Peptide | To map interaction sites and measure binding affinity for anti-apoptotic proteins. |

| Liposomes (with mitochondrial lipid composition) | Lipid Vesicle | In vitro reconstitution of MOMP to study pore formation by BAX/BAK. |

| BH3 Mimetics (e.g., Venetoclax, Navitoclax) | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Tool compounds to specifically inhibit anti-apoptotic proteins in cellular and in vivo models. |

| BAX/BAK Double-Knockout Cell Lines | Cellular Model | To definitively establish the requirement of these effectors for intrinsic apoptosis. |

The following workflow diagram maps the key experimental approaches from initial protein study to functional validation.

Therapeutic Targeting of the BCL-2 Family in Human Disease

The pivotal role of the BCL-2 family in controlling apoptosis makes it an attractive target for cancer therapy. BH3 mimetics are a class of small-molecule drugs designed to occupy the hydrophobic groove of anti-apoptotic proteins, thereby disrupting their protective function and freeing pro-apoptotic proteins to trigger apoptosis in malignant cells [15] [13].

Venetoclax (ABT-199), a highly selective BCL-2 inhibitor, has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in the treatment of certain hematological malignancies, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [15] [13]. Its clinical success validates the mechanism of directly targeting the BCL-2 family to reactivate apoptosis. However, resistance can emerge through various mechanisms, including upregulation of other anti-apoptotic proteins like MCL-1 or mutations in BCL-2 itself (e.g., F104L/C) that reduce drug binding affinity without impairing pro-survival function [13]. These challenges have spurred the development of next-generation mimetics targeting MCL-1 and BCL-xL, as well as combination regimens designed to overcome resistance.

The BCL-2 family operates as an exquisitely regulated signaling hub, interpreting a vast array of intracellular signals to govern the commitment to mitochondrial apoptosis via cytochrome c release. Continued structural and mechanistic research is deepening our understanding of the complex interactions between its members. The successful translation of this knowledge into clinical therapies, exemplified by BH3 mimetics, highlights the profound impact of fundamental apoptosis research. Future efforts will focus on refining these targeted agents, overcoming resistance mechanisms, and expanding their utility across a broader spectrum of cancers.

The intrinsic apoptosis pathway represents a crucial cellular defense mechanism, eliminating damaged or potentially dangerous cells through a mitochondria-dependent process. Central to this pathway is cytochrome c (cyt c), a multifunctional protein that normally resides in the mitochondrial intermembrane space, where it serves as an essential electron carrier in the respiratory chain [5] [14]. Upon reception of potent intracellular stress signals, cyt c is released into the cytosol, where it initiates the assembly of the apoptosome complex, leading to caspase activation and programmed cell death [14] [16].

Understanding the specific molecular triggers that provoke cyt c release is fundamental to cancer biology, neurodegenerative research, and therapeutic development. This technical guide examines the principal intrinsic stimuli—DNA damage, oxidative stress, and metabolic dysfunction—detailing their mechanisms, experimental assessment, and interplay within the context of cyt c-mediated apoptosis. The focused examination of these triggers provides critical insights for manipulating cell death pathways in disease intervention, particularly in cancer treatment where resistance to apoptosis constitutes a hallmark of malignancy [5] [16].

Molecular Triggers of Cytochrome c Release

DNA Damage

DNA damage activates sophisticated sensor networks that ultimately converge on mitochondria to initiate apoptosis. Genotoxic insults from both exogenous sources (e.g., ionizing radiation, chemotherapeutic agents) and endogenous sources (e.g., replication stress, reactive oxygen species) trigger signaling cascades primarily mediated by the p53 tumor suppressor protein [17]. Activated p53 transcribes pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, including Bax and Bak, which translocate to mitochondria where they oligomerize and facilitate mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), enabling cyt c release [14].

The specific type of DNA lesion influences the activation kinetics and magnitude of the apoptotic response. Double-strand breaks typically engage the ATM-Chk2 pathway, while replication stress and single-strand breaks activate ATR-Chk1 signaling. Both pathways stabilize and activate p53, connecting nuclear damage to mitochondrial apoptosis [17]. Additionally, DNA damage can promote cyt c release through p53-independent mechanisms involving direct activation of pro-apoptotic proteins or through metabolic disruptions.

Table 1: DNA Damage Types and Their Impact on Cytochrome c Release

| Damage Type | Primary Sensors | Key Signaling Components | Effect on Cytochrome c Release |

|---|---|---|---|

| Double-strand breaks | ATM, DNA-PK | p53, Bax, PIDDosome | Strong induction via Bak/Bax oligomerization |

| Oxidative base damage (8-oxoG) | OGG1, APE1 | PARP1, XRCC1 | Moderate induction; context-dependent |

| Replication stress | ATR, Chk1 | p53, Caspase-2 | Delayed but sustained release |

| Bulky adducts | NER machinery | p53, p73 | Variable induction based on repair efficiency |

Oxidative Stress

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) function as double-edged swords in cellular physiology—at physiological levels, they participate in signaling pathways, but at pathological levels, they induce oxidative stress that triggers apoptosis [18]. Key ROS include superoxide anion (O₂•⁻), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), and the highly reactive hydroxyl radical (•OH). Mitochondria represent both a primary source and target of ROS, creating amplification loops that promote cyt c release [18].

Oxidative stress facilitates cyt c release through multiple interconnected mechanisms. ROS directly oxidize cardiolipin, a phospholipid that anchors cyt c to the inner mitochondrial membrane [14]. Cardiolipin oxidation reduces its binding affinity for cyt c, mobilizing the protein within the intermembrane space and facilitating its release through permeabilized outer membranes [5]. Additionally, ROS activate several Bcl-2 family proteins, inhibit anti-apoptotic proteins through oxidation, and induce permeability transition pore opening, collectively promoting MOMP [18].

The redox state of cyt c itself influences its apoptotic function. Reduced cyt c (Fe²⁺) is more effective in caspase activation compared to oxidized cyt c (Fe³⁺), and cancer cells often exhibit altered cyt c redox states that may contribute to apoptosis resistance [16].

Metabolic and Other Intrinsic Stimuli

Beyond classical triggers, various metabolic disturbances can initiate intrinsic apoptosis. Nutrient deprivation, growth factor withdrawal, and severe metabolic stress engage pro-apoptotic signaling through multiple pathways, including impaired ATP production, disrupted calcium homeostasis, and altered NAD+/NADH ratios [19].

The Warburg effect, wherein cancer cells preferentially utilize glycolysis despite oxygen availability, represents a metabolic adaptation with implications for apoptosis sensitivity. Interestingly, despite reduced mitochondrial content in some cancers, respiratory capacity per mitochondrion may be enhanced through bioenergetic adaptations, creating potential vulnerabilities for targeted therapies [19]. ER stress represents another potent trigger, where unfolded protein accumulation activates the PERK-ATF4-CHOP pathway, transcriptionally upregulating pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members that promote cyt c release [5].

Experimental Analysis of Trigger Mechanisms

Detection Methods for Cytochrome c Release

Establishing robust experimental protocols is essential for investigating cyt c release mechanisms. The following methodologies represent gold standards in the field:

Immunofluorescence Microscopy: This technique visualizes cyt c localization in fixed cells. Under normal conditions, cyt c displays a punctate mitochondrial pattern that becomes diffuse upon apoptosis induction. The protocol involves: (1) culturing cells on glass coverslips; (2) applying apoptotic stimuli; (3) fixation with paraformaldehyde; (4) permeabilization with Triton X-100; (5) blocking with BSA; (6) incubation with anti-cytochrome c antibody; (7) fluorescent secondary antibody detection; and (8) confocal microscopy imaging. Co-staining with mitochondrial markers (e.g., TOM20) confirms release completeness [14].

Subcellular Fractionation and Western Blotting: This biochemical approach quantifies cyt c redistribution. Cells are fractionated into mitochondrial and cytosolic components using differential centrifugation. The protocol includes: (1) gentle homogenization to preserve mitochondrial integrity; (2) sequential centrifugation at 800×g to remove nuclei and 10,000×g to pellet mitochondria; (3) high-speed centrifugation (100,000×g) to obtain cytosolic fraction; (4) Western blotting of fractions using anti-cytochrome c antibody. Purity of fractions should be verified using compartment-specific markers (e.g., COX IV for mitochondria, LDH for cytosol) [14].

Live-Cell Imaging with Fluorescent Proteins: Real-time tracking of cyt c release employs cells expressing cyt c-GFP fusion proteins or stained with cyt c-specific fluorescent probes (e.g., Alexa Fluor-labeled antibodies introduced via streptolysin O permeabilization). This approach reveals kinetics and heterogeneity of release responses within cell populations [14].

Assessing DNA Damage-Induced Apoptosis

Comprehensive evaluation of DNA damage-triggered cyt c release requires integrated assessment of DNA lesion formation, damage signaling, and mitochondrial engagement:

γH2AX Immunostaining: Phosphorylated histone H2AX (γH2AX) foci quantification serves as a sensitive marker for double-strand breaks. Cells are fixed and stained with anti-γH2AX antibody followed by fluorescent secondary antibody. Foci are counted manually or using automated imaging systems, with correlation to cyt c release timing [17].

Comet Assay: Single-cell gel electrophoresis detects DNA strand breaks at the individual cell level. Cells are embedded in agarose, lysed, subjected to electrophoresis, stained with DNA-binding dye, and analyzed for tail moment (reflecting DNA damage). This technique reveals heterogeneity in damage response [17].

Western Blotting for DNA Damage Signaling: Key signaling components including phospho-ATM, phospho-Chk2, phospho-p53, and total p53 levels are monitored by Western blot following genotoxic insult. Temporal analysis establishes signaling kinetics relative to cyt c release [17].

Monitoring Oxidative Stress Involvement

Determining ROS contribution to cyt c release employs multiple complementary approaches:

Fluorescent ROS Sensors: Cell-permeable dyes (e.g., H₂DCFDA for general ROS, MitoSOX for mitochondrial superoxide) provide dynamic assessment of oxidative stress. Cells are loaded with dye, exposed to apoptotic stimuli, and fluorescence is measured by flow cytometry or microscopy. Concurrent monitoring of mitochondrial membrane potential (with TMRE or JC-1) helps establish causal relationships [18].

Cardiolipin Oxidation Assessment: Antibodies specific to oxidized cardiolipin enable detection of this key event in cyt c mobilization. Immunofluorescence or flow cytometry with anti-oxidized cardiolipin antibody (e.g., clone 2C6) reveals cardiolipin oxidation preceding cyt c release [5].

Antioxidant Interventions: Pharmacological (e.g., N-acetylcysteine, mito-TEMPO) or genetic (e.g., SOD overexpression) antioxidant approaches test necessity of ROS in cyt c release. Attenuation of release with specific antioxidants implicates particular ROS species in the process [18].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Studying Cytochrome c Release

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application/Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Damage Inducers | Etoposide, Camptothecin, UV-C radiation | Induce specific DNA lesion types to trigger apoptosis | Dose-response critical; consider cell type sensitivity |

| Oxidative Stress Probes | H₂DCFDA, MitoSOX Red, MitoTracker | Detect and quantify ROS production and localization | Confirm specificity with appropriate controls |

| Apoptosis Inhibitors | Z-VAD-FMK (pan-caspase), Cyclosporin A (MPTP inhibitor) | Determine caspase-dependence and MPTP involvement | Use multiple concentrations to verify specificity |

| Antibodies for Detection | Anti-cytochrome c, Anti-COX IV, Anti-γH2AX | Assess subcellular localization and damage markers | Validate specificity with knockout/knockdown controls |

| Mitochondrial Dyes | TMRE, JC-1, MitoTracker | Monitor membrane potential and morphology | Correlate depolarization with cyt c release timing |

Integrated Signaling Pathways

The molecular triggers of cyt c release engage in extensive crosstalk, creating a network that integrates diverse stress signals into a commitment to apoptosis. DNA damage, oxidative stress, and metabolic perturbations often co-occur and amplify each other—for example, DNA damage increases ROS production, which exacerbates additional DNA lesions and lipid peroxidation [17] [18].

The pathway diagram below illustrates the convergence of multiple stress signals on mitochondrial cyt c release:

Integrated Stress Signaling to Cytochrome c Release

This integrated network demonstrates how disparate stress signals converge on mitochondrial regulation, with Bcl-2 family proteins serving as central gatekeepers. The relative contribution of each pathway varies by cell type and stressor intensity, creating context-specific apoptotic responses that can be leveraged for therapeutic targeting.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Advancing research on cyt c release mechanisms requires specialized reagents and tools. The following table summarizes essential research solutions for investigating intrinsic apoptotic triggers:

Table 3: Advanced Research Tools for Cytochrome c Release Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Products | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyt c Release Assay Kits | Abcam Cytochrome c Release Assay Kit, BioVision Cytochrome c Release Apoptosis Assay Kit | Standardized measurements of cyt c translocation | Compare mitochondrial vs. cytosolic fractions; include integrity controls |

| Genetically Encoded Sensors | cyto-GFP (cyt c-GFP fusion), RFP-cyto-GFP (dual localization) | Real-time tracking of release kinetics in live cells | Verify normal respiratory function after labeling |

| ROS/RNS Detection Probes | CellROX series, DAF-FM diacetate, MitoPY1 | Specific detection of different reactive species | Confirm subcellular localization with compartment markers |

| DNA Damage Reporter Cells | 53BP1-GFP, MDC1-GFP reporter lines | Correlate DNA damage foci with apoptotic commitment | Establish baseline foci counts for cell type |

| Bcl-2 Family Modulators | ABT-199 (venetoclax), AMA-37 (Bax activator) | Test specific protein requirements in release | Use multiple structurally distinct modulators to confirm effects |

| Mitochondrial Isolation Kits | MITOISO2, Abcam Mitochondrial Isolation Kit | Obtain pure mitochondrial fractions for in vitro studies | Assess cross-contamination with other compartments |

Therapeutic Implications and Research Perspectives

The molecular triggers of cyt c release represent promising targets for therapeutic intervention, particularly in oncology where apoptosis evasion is fundamental to pathogenesis [16]. Chemotherapeutic agents and radiotherapy intentionally induce DNA damage to activate cyt c release in cancer cells, while resistance mechanisms often involve upregulation of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins [5] [16].

Emerging strategies include direct targeting of cyt c interactions, such as promoting its release using BH3 mimetics that neutralize anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins, or sensitizing cancer cells to cyt c-mediated caspase activation by modulating its redox state [16]. Natural compounds like apigenin, moringa isothiocyanate, and diallyl trisulfide demonstrate promising pro-apoptotic effects through mitochondrial targeting in preclinical breast cancer models [16].

Future research directions should focus on single-cell analysis of cyt c release heterogeneity, structural biology of cyt c interactions with cardiolipin and APAF-1, and development of trigger-specific biomarkers predicting therapeutic response. The complex interplay between metabolic reprogramming, oxidative stress regulation, and apoptosis sensitivity presents particularly fertile ground for investigation, especially in the context of tumor-specific metabolic dependencies [19].

Understanding the precise molecular triggers of cytochrome c release provides not only fundamental insights into cellular homeostasis but also practical therapeutic opportunities for manipulating cell death in human disease.

Mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) is a decisive event in the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis, serving as the primary mechanism responsible for cytochrome c release and the subsequent activation of caspases that execute cell death [20] [21]. This process is meticulously regulated by the B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) family of proteins, which integrate diverse apoptotic stimuli to determine cellular fate [20] [14]. The permeabilization of the mitochondrial outer membrane allows proteins normally confined to the intermembrane space, such as cytochrome c and SMAC/DIABLO, to escape into the cytosol [20] [14]. Once in the cytosol, cytochrome c facilitates the formation of the apoptosome, a complex that activates caspase-9 and initiates a proteolytic cascade leading to apoptotic cell dismantling [22] [14].

Understanding MOMP is not merely of academic interest but holds significant therapeutic potential. Dysregulation of apoptosis is a hallmark of cancer, with many malignancies exhibiting overexpression of anti-apoptotic proteins to evade cell death [20] [22]. Conversely, excessive apoptosis contributes to neurodegenerative diseases and tissue damage [22] [23]. Therefore, elucidating the molecular mechanisms governing MOMP, including the critical role of membrane lipids and protein-lipid interactions, provides crucial insights for developing novel therapeutics that can modulate cell death pathways in human diseases [24].

BCL-2 Protein Family: Master Regulators of MOMP

The BCL-2 protein family serves as the central regulatory module controlling MOMP through a delicate balance between pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic signals [20] [21]. These proteins are classified structurally and functionally into three principal groups, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Classification and Function of BCL-2 Protein Family Members

| Category | Examples | BH Domains | Primary Function in Apoptosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-apoptotic | Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1 | BH1-BH4 | Bind and inhibit pro-apoptotic effectors; preserve membrane integrity [20] [22] |

| Pro-apoptotic Effectors | Bax, Bak, Bok | BH1-BH3 | Directly mediate MOMP through oligomerization and pore formation [20] [21] |

| BH3-only Proteins | Bid, Bim, Bad, Puma, Noxa | BH3 only | Sense cellular damage; activate Bax/Bak or inhibit anti-apoptotic members [20] [22] |

In healthy cells, Bax is predominantly cytosolic, while Bak is constitutively integrated into the mitochondrial outer membrane [24] [25]. Upon receipt of an apoptotic stimulus, BH3-only proteins become activated and initiate a cascade that culminates in Bax/Bak activation [20]. The "activator" BH3-only proteins (e.g., Bid, Bim) directly engage Bax and Bak, inducing conformational changes that expose their membrane-insertion domains [20] [21]. Meanwhile, "sensitizer" BH3-only proteins (e.g., Bad, Noxa, Puma) function by neutralizing anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins, thereby displacing their inhibitory hold on Bax and Bak [20] [22]. This intricate interplay ensures that MOMP proceeds only when the balance definitively shifts in favor of pro-apoptotic signals.

Diagram: BCL-2 Protein Regulation of MOMP

Molecular Mechanisms of Pore Formation

The precise architecture of the apoptotic pore remains a subject of intense investigation, with several models proposed to explain how Bax and Bak permeabilize the mitochondrial outer membrane.

Bax/Bak Oligomerization and Lipidic Pores

The prevailing model suggests that activated Bax and Bak undergo extensive oligomerization, forming large complexes that ultimately disrupt membrane integrity [20] [25]. These oligomers are thought to create proteolipidic pores where both protein and lipid components contribute to the pore structure [24] [26]. This model shares similarities with the "toroidal pore" mechanism described for antimicrobial peptides, where lipid headgroups line the pore interior alongside protein elements [26]. Evidence for this includes the observation that Bax and Bak can form ring-like structures visible by electron microscopy [24], and that pore formation is influenced by membrane lipid composition [24] [25].

A landmark study using lipid nanodisc technology to isolate BAK in near-native membrane environments revealed that the local lipid environment surrounding BAK assemblies becomes significantly enriched in unsaturated lipid species during apoptosis [24]. This lipid unsaturation was shown to actively promote BAX pore activity in model membranes, isolated mitochondria, and cellular systems [24]. Molecular dynamics simulations further supported these findings, demonstrating enrichment of unsaturated lipids at the pore rim and suggesting they facilitate membrane curvature necessary for pore formation [24].

Catalytic Pore Facilitation Model

Interestingly, studies using native mitochondrial outer membranes (MOMs) revealed that Bax-mediated pore formation occurs more efficiently in biological membranes than in synthetic liposomes, suggesting resident MOM proteins facilitate this process [25]. Kinetic analyses demonstrated a distinct lag phase in native membranes not observed in liposomes, leading to a proposed two-tiered model where Bax activation first promotes assembly of a multimeric complex (the "catalyst"), which then facilitates Bax-dependent pore formation [25]. This catalyst appears distinct from Bax itself and exhibits phase transition-like behavior sensitive to membrane lipid packing [25]. While the identity of this catalyst remains unknown, its existence underscores the complexity of MOMP in physiological contexts.

Diagram: Pore Formation Models in MOMP

Cytochrome c Release in the Intrinsic Pathway

Cytochrome c plays a dual role in cellular physiology—in healthy mitochondria, it resides in the intermembrane space where it functions as an essential electron shuttle in the respiratory chain, but upon MOMP, it becomes a potent apoptotic activator when released into the cytosol [14] [27]. The release process involves at least two critical phases: mobilization from its membrane associations and translocation through the permeabilized outer membrane.

In its physiological role, a significant proportion of cytochrome c is electrostatically bound to cardiolipin, a mitochondria-specific phospholipid located primarily in the inner membrane [14]. The interaction between cytochrome c (net charge +8 at physiological pH) and anionic cardiolipin occurs through both electrostatic bonding and hydrophobic interactions, with one acyl chain of cardiolipin inserting into a hydrophobic channel of cytochrome c [14]. During apoptosis, cytochrome c must be mobilized from these cardiolipin associations, potentially through cardiolipin oxidation by reactive oxygen species (ROS) or phospholipase A2 activity, which significantly reduces cytochrome c's binding affinity [14]. Alternatively, increased cytosolic calcium levels may weaken the electrostatic interaction, facilitating detachment [14].

Once mobilized, cytochrome c translocates to the cytosol through Bax/Bak-dependent pores in the outer membrane [14] [27]. This release is remarkably rapid and complete in apoptotic cells, occurring within approximately 5 minutes of MOMP induction [21]. In the cytosol, cytochrome c binds to Apoptotic Protease-Activating Factor 1 (Apaf-1), promoting the formation of the apoptosome complex which activates caspase-9, ultimately leading to caspase-3 activation and apoptotic cell death [22] [14].

Table 2: Key Events in Cytochrome c Release and Apoptosis Activation

| Event | Key Players | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Cytochrome c Mobilization | Cytochrome c, Cardiolipin, ROS, Calcium | Detachment from inner membrane observed in isolated mitochondria; cardiolipin oxidation reduces binding affinity [14] |

| Pore Formation | Bax, Bak, Lipid co-factors | Bax/Bak oligomers visualized by EM; liposome permeabilization assays; BAX/BAK DKO cells resistant to MOMP [20] [24] [21] |

| Cytochrome c Release | Permeabilized MOM, IMS proteins | Live-cell imaging shows rapid, complete release; detected by immunofluorescence and subcellular fractionation [14] [21] |

| Apoptosome Formation | Cytochrome c, Apaf-1, Caspase-9 | Reconstituted in cell-free systems; deficient in cytochrome c knockout cells [22] [14] |

| Caspase Activation | Caspase-9, Caspase-3/7 | Cleavage assays and FRET-based reporters; blocked by caspase inhibitors [22] [14] |

Role of Membrane Lipid Composition in MOMP

Emerging research has illuminated the critical influence of membrane lipid composition on MOMP regulation, moving beyond the traditional protein-centric view. The mitochondrial outer membrane possesses a unique lipid composition that differs from other cellular membranes, and this composition appears dynamically regulated during apoptosis [24].

A groundbreaking 2024 study employed comparative lipidomics of BAK isolated in lipid nanodiscs and revealed a significant enrichment of unsaturated lipid species in the proximal membrane environment of BAK during apoptosis [24]. Specifically, phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) showed increased polyunsaturated species at the expense of saturated forms in apoptotic mitochondrial membranes [24]. Functional experiments demonstrated that unsaturated lipids directly promote BAX pore activity across model membrane systems, isolated organelles, and cellular contexts [24]. Accordingly, depletion of FADS2, a key enzyme in fatty acid poly-unsaturation, decreased apoptosis sensitivity and activation of the cGAS/STING pathway downstream of mitochondrial DNA release [24].

The significance of specific lipid species extends beyond unsaturation. Cardiolipin, a mitochondrial signature phospholipid, has been implicated in BAX activity and oligomerization [24] [14]. While cardiolipin is predominantly located in the inner mitochondrial membrane, it is present in the outer membrane at lower concentrations (approximately 1-3% of total lipid content) and may facilitate Bax membrane insertion and oligomerization [24] [14]. The emerging paradigm suggests that local lipid microenvironments create favorable conditions for Bax/Bak activation and pore formation, with lipid composition serving as an critical regulatory layer in MOMP control.

Experimental Approaches for Studying MOMP

Investigating the dynamic process of MOMP requires a multifaceted methodological approach spanning biochemical, biophysical, and cell biological techniques.

Lipidomics and SMALP Isolation

The isolation of membrane protein complexes with their native lipid environment represents a significant advancement for studying protein-lipid interactions. As employed in recent research, this involves solubilizing mitochondrial membranes from apoptotic and healthy cells using styrene-maleic acid (SMA) copolymers, which form lipid nanodiscs (SMALPs) that preserve the native membrane environment [24]. BAK-containing SMALPs are then enriched via affinity purification (e.g., using GFP-Trap beads for tagged BAK) and subjected to lipid extraction for subsequent liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis [24]. This approach allows quantitative comparison of lipid species associated with BAK under different physiological states, revealing apoptosis-specific lipid changes such as increased polyunsaturated PC and PE species [24].

Kinetic Analysis of Pore Formation

Kinetic studies using isolated mitochondrial outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) have been instrumental in elucidating the multi-step nature of MOMP. The experimental protocol involves isolating OMVs from mouse liver mitochondria, loading them with fluorescent dextrans of varying sizes, and incubating with recombinant Bax and cBid (activator) while monitoring fluorescence dequenching due to dextran release [25]. Data analysis employs mathematical modeling to determine rate constants and identify distinct reaction phases. This approach revealed the lag phase characteristic of native MOMs and supported the catalyst-dependent model of pore formation [25].

Membrane Permeabilization Assays

Multiple complementary assays exist for monitoring membrane permeabilization in various experimental systems:

- Liposome leakage assays: Synthetic liposomes with defined lipid composition are loaded with fluorescent markers and incubated with recombinant BCL-2 proteins; marker release indicates membrane permeabilization [20] [26].

- Isolated mitochondria systems: Mitochondria isolated from tissues or cells are treated with apoptotic stimuli, and cytochrome c release is detected in supernatants by immunoblotting [24] [25].

- Live-cell imaging: Cells expressing fluorescent cytochrome c or stained with mitochondrial membrane potential dyes (e.g., TMRE) are monitored in real-time during apoptosis induction [22] [24].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Tools for MOMP Research

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Experimental Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Bax/Bak proteins | Study pore formation in vitro | Used in liposome and OMV assays to reconstitute MOMP [25] |

| BH3 mimetics (e.g., Venetoclax) | Inhibit anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins | Therapeutic compounds that induce apoptosis in cancer cells [22] |

| SMA copolymers | Solubilize membrane proteins with native lipids | Enable isolation of BAK with proximal lipid environment for lipidomics [24] |

| TMRE | Mitochondrial membrane potential dye | Loss of fluorescence indicates mitochondrial depolarization during early apoptosis [22] [24] |

| Caspase activity assays | Measure caspase-3/7 and caspase-9 activity | Fluorogenic substrates detect caspase activation downstream of MOMP [22] |

| Cytochrome c antibodies | Detect cytochrome c release | Immunoblotting and immunofluorescence to monitor localization [22] [14] |

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Lipidomics-MOMP Analysis

The mechanism of mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization represents a convergence point for protein-protein and protein-lipid interactions that collectively determine cellular fate. While significant progress has been made in understanding the roles of BCL-2 family proteins in initiating MOMP, emerging research highlights the critical contribution of membrane lipid composition, particularly lipid unsaturation, in facilitating Bax/Bak pore formation [24]. The integration of structural, biochemical, and biophysical approaches continues to refine our understanding of the apoptotic pore architecture, with current evidence supporting a model where activated Bax and Bak form proteolipidic pores whose activity is enhanced by specific lipid environments and potentially facilitated by additional mitochondrial factors [24] [25] [26].

For drug development professionals, these mechanistic insights offer promising therapeutic avenues. The demonstration that lipid desaturase activity influences apoptosis sensitivity suggests that modulation of membrane lipid composition might represent a novel strategy for overcoming apoptosis resistance in cancer cells [24]. Similarly, the development of BH3 mimetics that target specific anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family members exemplifies how basic research on MOMP regulation can translate into clinically effective therapies [22]. Future research aimed at definitively identifying the catalytic component(s) that facilitate Bax pore formation in native membranes, and further elucidating the spatial and temporal dynamics of lipid changes during apoptosis, will undoubtedly yield new opportunities for therapeutic intervention in diseases characterized by dysregulated cell death.

Cytochrome c is predominantly recognized for its fundamental role in the mitochondrial electron transport chain and its complete release during intrinsic apoptosis, leading to caspase activation and cell death. However, emerging research reveals a more complex paradigm in which cytochrome c exhibits functions beyond this all-or-nothing phenomenon. This review synthesizes current understanding of sub-lethal cytochrome c signaling and partial mobilization events, examining molecular mechanisms, regulatory processes, and functional consequences. We explore how partial release contributes to cellular homeostasis, differentiation, and DNA damage response without triggering full apoptosis. The article provides comprehensive quantitative analysis of cytochrome c release dynamics, detailed experimental protocols for studying sub-lethal mobilization, and essential research tools for investigating this nuanced aspect of cell biology. These insights refine our understanding of cellular life-death decisions and present novel therapeutic opportunities for cancer and degenerative diseases.

Cytochrome c is a multifunctional hemoprotein primarily known for its indispensable role in mitochondrial respiration, where it shuttles electrons between Complex III and Complex IV [14]. For decades, its apoptotic function has been characterized as an all-or-nothing process, where complete release from mitochondrial intermembrane space triggers apoptosome formation and caspase-mediated cell death [14] [28]. However, recent evidence challenges this binary perspective, revealing that cytochrome c can transmit sub-lethal signals through partial mobilization that influence cellular physiology without committing the cell to death [27].

This emerging paradigm recognizes that cytochrome c release occurs along a spectrum, with partial mobilization activating cellular processes distinct from full apoptosis. The concept of "partial release" suggests mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) may not invariably lead to cell death, allowing for limited cytochrome c redistribution with functional consequences [27]. Understanding these nuanced functions is critical for comprehending cellular adaptation to stress and developing targeted therapies that modulate rather than simply trigger cell death pathways.

The molecular mechanisms governing partial cytochrome c mobilization involve regulated alterations in mitochondrial membrane permeability controlled by BCL-2 family proteins, without complete commitment to the apoptotic cascade [14] [28]. This review examines the current evidence for sub-lethal cytochrome c functions, detailing the mechanisms of partial release, its functional consequences in cellular physiology and pathology, and advanced methodologies for its investigation.

Molecular Mechanisms of Partial Cytochrome c Mobilization

Regulatory Control by BCL-2 Family Proteins

The BCL-2 protein family serves as the primary regulator of cytochrome c release, maintaining a delicate balance between cell survival and death. This family comprises three functional groups: pro-apoptotic effector proteins (Bax, Bak, Bok), pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins (Bid, Bad, Bim, Puma, Noxa), and anti-apoptotic proteins (Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Bcl-w, Mcl-1) [28] [22]. In the intrinsic pathway, cellular stresses like DNA damage or oxidative stress activate BH3-only proteins, which then engage and activate Bax and Bak. These effectors oligomerize to form pores in the mitochondrial outer membrane, facilitating cytochrome c release [28].

The extent of cytochrome c release is determined by the dynamic equilibrium between these opposing BCL-2 family members. Partial cytochrome c mobilization occurs when this equilibrium is subtly perturbed rather than completely disrupted, resulting in limited permeabilization of the mitochondrial outer membrane. This can happen through several mechanisms: moderate activation of BH3-only proteins, incomplete Bax/Bak oligomerization, or transient pore formation that allows limited cytochrome c passage without complete mitochondrial commitment to apoptosis [14] [27]. The heterogeneity of mitochondrial populations within single cells further contributes to this partial release phenomenon, with some mitochondria releasing their cytochrome c content while others remain intact [27].

Cytochrome c-Cardiolipin Interactions and Mobilization

Within mitochondria, cytochrome c is anchored to the inner membrane through associations with the phospholipid cardiolipin, which governs its retention and mobilization [14]. At physiological pH, cytochrome c carries a net positive charge (+8), facilitating strong electrostatic interactions with anionic cardiolipin molecules. Additionally, cytochrome c contains a hydrophobic channel through which one acyl chain of cardiolipin can insert, while the remaining chains remain embedded in the membrane, providing dual-mode anchoring [14].

Detachment of cytochrome c from cardiolipin represents a critical step in its mobilization and can occur through several mechanisms. Cardiolipin oxidation significantly reduces its affinity for cytochrome c, facilitating release [14]. This oxidation can be mediated by reactive oxygen species (ROS), phospholipase A2, or the cardiolipin-cytochrome c complex itself, with the latter process potentially accelerated by conformational changes in cytochrome c when bound to cardiolipin [14]. Increased cytosolic calcium concentrations can also weaken the electrostatic interaction between cytochrome c and cardiolipin, promoting detachment [14]. In partial release scenarios, these processes may occur in a limited, compartmentalized manner rather than throughout the entire mitochondrial network.

Permeabilization Thresholds and Sub-apoptotic Signaling

The concept of a permeabilization threshold is central to understanding partial cytochrome c mobilization. Cells may exhibit heterogeneity in their susceptibility to MOMP, with variations in BCL-2 family expression profiles, mitochondrial membrane composition, and cellular stress response pathways influencing this threshold [27]. Sub-lethal stress signals may induce MOMP in only a subset of mitochondria or create pores that permit limited cytochrome c efflux without complete cellular commitment to apoptosis.

In these scenarios, the limited cytochrome c released into the cytosol may be insufficient to fully activate the apoptosome and caspase cascade, especially given the high ATP concentration required for apoptosome formation (approximately 0.5-5 mM cytochrome c in the intermembrane space) [29]. Instead, sub-apoptotic cytochrome c concentrations may engage alternative signaling pathways or produce localized effects that influence cellular physiology without triggering death. The presence of endogenous inhibitors, including IAP (Inhibitor of Apoptosis Proteins) families, may further buffer against full caspase activation following limited cytochrome c release [30].

Quantitative Analysis of Cytochrome c Release Dynamics

Parameters of Partial Cytochrome c Release

Advanced quantification techniques have revealed that cytochrome c release exists along a continuum rather than as a binary event. The following table summarizes key quantitative parameters associated with partial versus complete cytochrome c mobilization, derived from experimental studies using fluorescence imaging, subcellular fractionation, and cytochrome c-GFP tracking systems [29].

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters of Cytochrome c Release

| Parameter | Partial Release | Complete Release | Measurement Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Cellular Cytochrome c Released | 10-30% | 70-100% | Cellular fractionation with Western blot densitometry [29] |

| Mitochondria Affected | 15-40% of mitochondria per cell | >80% of mitochondria per cell | Cytochrome c-GFP fluorescence tracking [29] |

| Caspase-3 Activation | Minimal or absent (≤15% of full activation) | Robust (>80% of maximum) | Fluorogenic caspase-3 substrate cleavage assays [31] |

| Cytochrome c Release Kinetics | Slow, asynchronous over 2-6 hours | Rapid, synchronous within 30 minutes | Live-cell imaging of cytochrome c-GFP [29] |

| Cell Fate Outcome | Survival with modified function | Apoptotic death | Long-term cell tracking and viability assays [27] |

| ATP Concentration for Apoptosome Formation | Below threshold (~0.5-1 mM) | Above threshold (>1 mM) | ATP depletion/addition experiments [14] |

Biochemical Regulation of Release Thresholds

The transition between partial and complete cytochrome c release is governed by precise biochemical regulation. The affinity between cytochrome c and APAF-1, crucial for apoptosome formation, depends on specific molecular interactions. Lys72 of cytochrome c is particularly critical for stable interaction with APAF-1, with mutations at this position (e.g., Lys72Ala) substantially reducing apoptotic activity while preserving respiratory function [14]. In knock-in mice, the Lys72Ala mutation results in embryonic lethality and brain developmental defects similar to APAF-1 and caspase-9 knockouts, confirming the functional significance of this interaction [14].

The ionic strength of the cellular environment significantly influences cytochrome c release dynamics. Experimental studies using isolated mitochondria have demonstrated that physiological potassium concentrations (50-80 mM) can promote cytochrome c release from the inner mitochondrial membrane without requiring additional biochemical events [14]. This suggests that physiological fluctuations in intracellular ion concentrations may contribute to partial cytochrome c mobilization under sub-lethal conditions.

Table 2: Molecular Determinants of Cytochrome c Release Thresholds

| Regulatory Factor | Effect on Release Threshold | Impact on Partial Release |

|---|---|---|

| BCL-2/Bax Ratio | High ratio increases threshold, low ratio decreases it | Moderate ratios favor partial release [28] |

| Cardiolipin Oxidation State | Increased oxidation lowers retention capacity | Moderate oxidation enables selective release [14] |

| Ionic Strength | High K+ (50-80 mM) promotes mobilization | Physiological fluctuations may regulate partial release [14] |

| Cytochrome c Mutations (e.g., Lys72Ala) | Disrupts APAF-1 binding | Permits respiratory function without apoptosis [14] |

| Cristae Remodeling | Facilitates complete cytochrome c pool access | Limited remodeling may restrict release [14] |

Experimental Approaches for Studying Sub-lethal Cytochrome c Functions

Quantitative Assay for Cytochrome c Release

Accurately quantifying cytochrome c release patterns is essential for distinguishing partial from complete mobilization. The digitonin-based selective permeabilization assay coupled with flow cytometry provides a robust method for this purpose [29]. This approach enables rapid, non-subjective quantification of cells with cytoplasmic cytochrome c in both adherent and non-adherent populations.

Protocol for Quantitative Cytochrome c Release Assay [29]:

Cell Preparation: Harvest approximately 1×10^5 cells and wash with PBS containing 100 mM KCl to maintain physiological ionic strength.

Selective Permeabilization: Treat cells with 100 μl digitonin (50 μg/ml in PBS with 100 mM KCl) for 5 minutes on ice. Monitor permeabilization efficiency using trypan blue exclusion (>95% permeabilization indicates optimal treatment).

Fixation: Add paraformaldehyde (4% in PBS) for 20 minutes at room temperature to preserve subcellular structures. Wash three times with PBS.

Blocking and Staining: Incubate cells in blocking buffer (3% BSA, 0.05% saponin in PBS) for 1 hour. Then incubate overnight at 4°C with anti-cytochrome c monoclonal antibody (e.g., clone 6H2.B4) diluted 1:200 in blocking buffer.

Detection: Wash cells three times and incubate for 1 hour at room temperature with PE-labeled secondary antibody (1:200 dilution in blocking buffer). Analyze by flow cytometry detecting PE fluorescence in FL-2 channel.

Controls and Validation: Include untreated cells as high fluorescence controls and cells with full cytochrome c release (e.g., treated with apoptotic inducers) as low fluorescence controls. Confirm FACS analysis by fluorescence microscopy.

This method offers significant advantages over Western blot-based approaches, which provide averaged results from cell populations and cannot distinguish whether all cytochrome c is cytoplasmic in a small percentage of cells or all cells have partially redistributed their cytochrome c [29]. The flow cytometry approach captures this heterogeneity at single-cell resolution.

Monitoring Partial Release in Live Cells

For real-time monitoring of cytochrome c release dynamics, live-cell imaging of cytochrome c-GFP provides unparalleled temporal resolution [29]. This approach reveals that cytochrome c release in individual cells is rapid and complete once initiated, but the timing varies between cells within a population. For studying partial release, this technique can be combined with mild apoptotic stimuli or stress conditions that don't trigger full commitment to apoptosis.

Critical considerations for live-cell imaging:

- Use low-level GFP expression to avoid artifacts from protein overexpression

- Employ photostable fluorophores and minimize phototoxicity during time-lapse imaging

- Correlate cytochrome c release with mitochondrial membrane potential using dyes like TMRE

- Combine with caspase activity reporters to distinguish sub-lethal from lethal release

Non-Apoptotic Functions of Cytochrome c

Regulation of DNA Damage Response

Emerging evidence indicates that cytochrome c participates in DNA damage response pathways independently of its apoptotic function. Caspases, particularly caspase-3 and caspase-7, can directly cleave DNA repair proteins, modulating their activity in ways that influence genomic stability [31]. For example, caspase-mediated cleavage of PARP-1 [poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1] inhibits DNA repair during apoptosis, but at sub-lethal levels may fine-tune DNA damage response [31].

In the absence of full apoptosis, limited cytochrome c release and subsequent low-level caspase activation may influence cell cycle checkpoints and DNA repair efficiency. Caspase-2, activated in response to DNA damage, can engage the intrinsic pathway without immediately triggering cell death, potentially through limited cytochrome c mobilization [31]. This sub-lethal signaling may provide a mechanism for eliminating cells with persistent DNA damage while allowing repair in less severely damaged cells.

Differentiation and Cellular Homeostasis

Sub-lethal cytochrome c signaling contributes to cellular differentiation and tissue homeostasis. During development, precise control of cell population sizes requires nuanced signaling beyond all-or-nothing apoptosis. Limited cytochrome c release may provide a mechanism for modulating cellular physiology without elimination [27].

In neuronal systems, sub-apoptotic cytochrome c release has been implicated in synaptic plasticity and remodeling, potentially through localized regulation of energy metabolism or modest activation of proteolytic cascades that modify cellular architecture without causing death. Similarly, in hematopoietic systems, partial cytochrome c mobilization may contribute to lineage commitment and differentiation decisions [27].

Research Tools and Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Sub-lethal Cytochrome c Functions

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytochrome c Detection Antibodies | Anti-cytochrome c clone 6H2.B4 [29] | Immunofluorescence, Western blotting | Specific for native conformation; works in fixed cells |

| Selective Permeabilization Agents | Digitonin [29] | Plasma membrane permeabilization | Selective cholesterol binding; preserves mitochondrial integrity |

| Apoptosis Inducers/Inhibitors | Venetoclax (BCL-2 inhibitor) [22], Campothecin [22] | Modulating release thresholds | Tool for establishing partial vs. complete release conditions |

| Live-Cell Imaging Tools | Cytochrome c-GFP constructs [29], MitoTracker Red [22], TMRE [22] | Real-time release kinetics | Enables single-cell analysis of release dynamics |

| Caspase Activity Assays | Fluorogenic caspase substrates (DEVD- AFC/AMC) [31] | Distinguishing sub-lethal vs. lethal release | Sensitive detection of low-level caspase activity |

| Mitochondrial Function Probes | JC-1, TMRM, MitoSOX [22] | Correlating release with mitochondrial status | Assesses membrane potential and ROS production |

| BCL-2 Family Modulators | ABT-737 (BH3 mimetic) [22], BIM peptides [28] | Regulating release thresholds | Tools for precise manipulation of MOMP |

Pathway Diagrams

Cytochrome c in Intrinsic Apoptosis and Sub-lethal Signaling

Experimental Workflow for Partial Release Detection

The paradigm of cytochrome c function has expanded significantly beyond its binary role in respiration and apoptosis. Evidence now compellingly demonstrates that cytochrome c participates in sub-lethal cellular signaling through partial mobilization events, creating a nuanced regulatory layer in cellular stress response. These partial release phenomena, governed by the BCL-2 family protein equilibrium and cytochrome c-cardiolipin interactions, enable cells to integrate stress signals without committing to apoptosis.

Understanding these mechanisms has profound implications for therapeutic development, particularly in cancer and degenerative diseases. In oncology, manipulating partial release thresholds may sensitize resistant tumors to treatment without excessive toxicity. Conversely, in neurodegenerative conditions, enhancing cellular capacity to manage sub-lethal cytochrome c release may promote neuronal survival. Future research should focus on precisely quantifying release thresholds, identifying molecular switches between partial and complete release, and developing targeted interventions that specifically modulate sub-lethal cytochrome c functions while preserving its essential roles in cellular metabolism.

Detecting and Harnessing Cytochrome c Release: Techniques and Therapeutic Applications

The intrinsic apoptotic pathway is a genetically programmed cell death process essential for development and tissue homeostasis, and its dysregulation is a hallmark of diseases ranging from neurodegeneration to cancer. At the core of this pathway lies cytochrome c (cyt c), a mitochondrial protein that plays a dual role in cellular survival and death. In healthy cells, cyt c functions as an electron shuttle in the respiratory chain within the mitochondrial intermembrane space. However, upon apoptotic stimulation, cyt c is released into the cytosol where it binds to Apaf-1, forming the apoptosome complex that activates caspase-9 and initiates a proteolytic cascade leading to cell dismantling [27]. The investigation of cyt c release mechanisms and regulation has relied heavily on two seemingly disparate experimental model systems: sympathetic neurons and cancer cell lines. This technical guide examines how these complementary models have advanced our understanding of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway, providing detailed methodologies, comparative analysis, and practical resources for researchers in the field.

Molecular Mechanisms of Cytochrome c Release

The Fundamental Process of Cytochrome c Release

Cytochrome c release from mitochondria represents a critical commitment point in the intrinsic apoptosis pathway. In healthy cells, cyt c is localized to the mitochondrial intermembrane and intercristae spaces, where it interacts with cardiolipin and functions in electron transport [27]. Multiple pro-apoptotic stimuli induce permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane, facilitating communication between intermembrane and intercristae spaces and promoting mobilization of cyt c from cardiolipin, enabling its release into the cytosol [27].

The released cyt c mediates the allosteric activation of apoptosis-protease activating factor 1 (Apaf-1), which is required for proteolytic maturation of caspase-9 and caspase-3 [27]. This cascade ultimately leads to apoptotic dismantling of the cell. However, research has revealed that cytosolic cyt c is also associated with vital cell functions such as differentiation, suggesting that its release does not always occur in an all-or-nothing fashion and that mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization may not invariably lead to cell death [27].

Key Regulatory Factors

The release and apoptotic activity of cyt c are regulated by multiple cellular factors:

- Bcl-2 Family Proteins: The pro-apoptotic protein Bax triggers cytochrome c efflux from mitochondria, while anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 prevents its redistribution [32].

- Redox Environment: The pro-apoptotic activity of cyt c is influenced by its redox state, with increases in reactive oxygen species (ROS) following apoptotic insults leading to oxidation and activation of cytochrome c [33].

- Glucose Metabolism: In healthy neurons and cancer cells, cyt c is reduced and held inactive by intracellular glutathione (GSH) generated through glucose metabolism via the pentose phosphate pathway [34].

Sympathetic Neuron Models

Experimental System Fundamentals