Decoding Cell Death: A Comprehensive Guide to the Morphological Features of Apoptosis vs. Necrosis for Biomedical Research

Accurately distinguishing between apoptosis and necrosis is fundamental in biomedical research, influencing everything from basic mechanistic studies to the evaluation of anticancer therapies.

Decoding Cell Death: A Comprehensive Guide to the Morphological Features of Apoptosis vs. Necrosis for Biomedical Research

Abstract

Accurately distinguishing between apoptosis and necrosis is fundamental in biomedical research, influencing everything from basic mechanistic studies to the evaluation of anticancer therapies. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, detailing the specific morphological hallmarks of each process. It explores foundational concepts, advanced label-free imaging techniques like Full-Field Optical Coherence Tomography (FF-OCT), common challenges in interpretation, and validation strategies. By synthesizing classical knowledge with cutting-edge methodologies, this guide aims to enhance the precision of cell death analysis in experimental and clinical settings, ultimately supporting more reliable drug discovery and development.

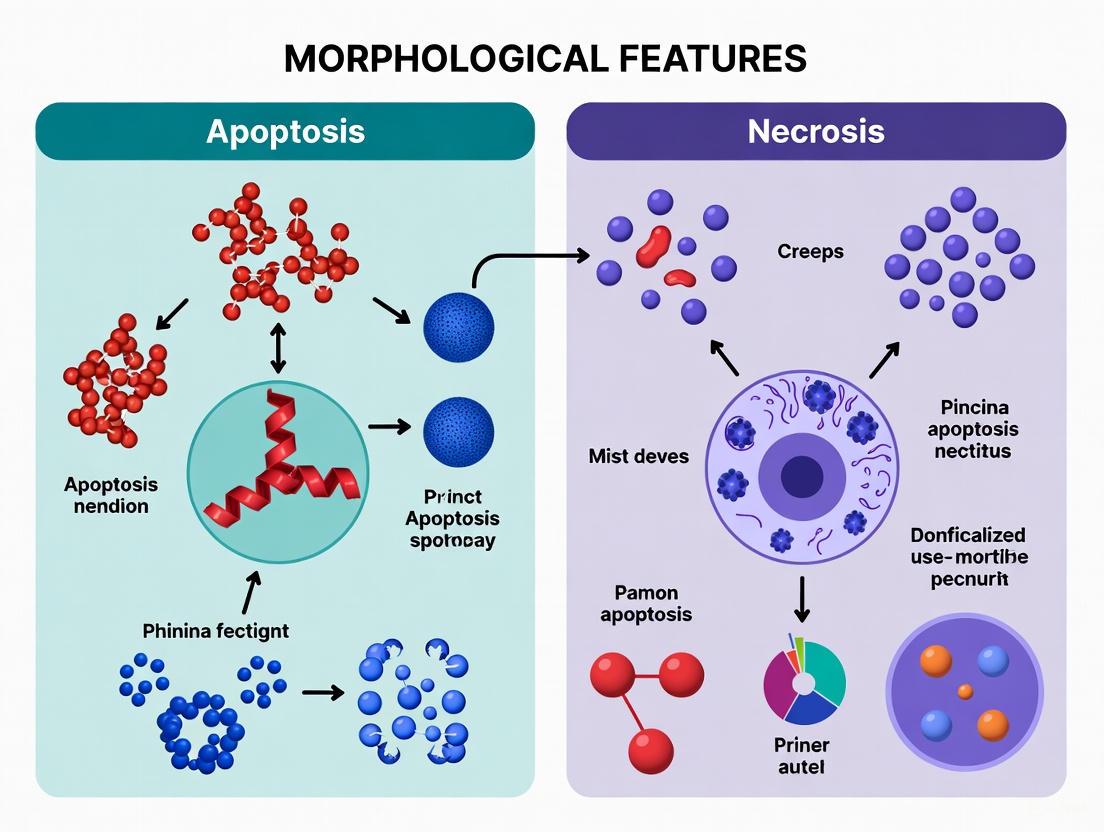

The Core Blueprint: Defining the Classical Morphological Hallmarks of Apoptosis and Necrosis

The precise identification of programmed cell death, or apoptosis, relies fundamentally on recognizing its unique morphological features, which stand in stark contrast to those of accidental cell death, or necrosis. These distinct morphological signatures are not merely descriptive; they are direct reflections of underlying biochemical pathways and have profound implications for tissue homeostasis and disease pathology. Apoptosis is a genetically regulated, energy-dependent process characterized by a tightly orchestrated series of structural changes, including cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, and formation of apoptotic bodies, all occurring without triggering an inflammatory response [1] [2]. In contrast, necrosis is an unregulated, passive process resulting from overwhelming external injury, leading to cell swelling, membrane rupture, and spillage of intracellular contents that incites inflammation [1] [3]. This guide provides a detailed, evidence-based comparison of these morphological hallmarks, underpinned by experimental data and methodologies essential for researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Morphology: Apoptosis vs. Necrosis

The following table summarizes the key morphological and physiological differences that form the basis for distinguishing between apoptosis and necrosis in experimental settings.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Apoptotic and Necrotic Cell Death

| Feature | Apoptosis | Necrosis |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Nature | Programmed, regulated, energy-dependent [1] | Accidental, unregulated, energy-independent [3] |

| Cellular Trigger | Physiological or mild pathological signals; developmental cues [2] [4] | Extreme physical/chemical injury; toxins, trauma, infection [1] [5] |

| Cell Size and Shape | Cell shrinkage, cytoplasmic condensation [2] [6] | Cell swelling (oncosis) [2] |

| Plasma Membrane | Blebbing with intact integrity; formation of apoptotic bodies [1] [4] | Loss of integrity; rupture and leakage of cellular contents [1] [3] |

| Nuclear Changes | Chromatin condensation (pyknosis), nuclear fragmentation (karyorrhexis) [2] [6] | Karyolysis (nuclear dissolution); pyknosis and karyorrhexis can also occur [2] |

| Organelles | Generally intact, though mitochondria may leak contents [1] | Swelling and disintegration of ER, mitochondria, and lysosomes [1] [2] |

| DNA Fragmentation | Endonuclease-cleaved into orderly fragments (DNA laddering) [5] | Random, diffuse degradation [5] |

| Phagocytic Clearance | Rapid engulfment of apoptotic bodies by macrophages/neighboring cells [2] [4] | Cell lysis; phagocytosis of debris, often incomplete [5] |

| Tissue Response | Affects individual cells; no inflammatory response [1] [2] | Affects groups of contiguous cells; prominent inflammatory response [1] [2] |

| Key Biomarkers | Caspase activation, phosphatidylserine externalization [3] [5] | Loss of ion homeostasis, ATP depletion [1] |

Visualizing the Key Signaling Pathways

The morphological changes in apoptosis are directly executed by molecular pathways. The following diagram illustrates the two principal routes of apoptosis induction.

Experimental Imaging and Assessment Protocols

High-Resolution Imaging with FF-OCT

Advanced label-free imaging techniques like Full-Field Optical Coherence Tomography (FF-OCT) allow for real-time, high-resolution monitoring of apoptotic morphology.

- Principle: FF-OCT is an interferometric technique that uses a broadband light source to generate high-resolution, cross-sectional images of cells based on light scattering, without requiring stains or labels [7].

- Protocol:

- Cell Preparation: Culture HeLa cells (or other relevant cell line) as a monolayer under standard conditions (e.g., DMEM, 37°C, 5% CO₂) [7].

- Induction of Death:

- Image Acquisition: Use a custom-built time-domain FF-OCT system with a halogen light source (e.g., center wavelength 650 nm) and high-NA water immersion objectives (e.g., 40x, NA=0.8). Initiate imaging immediately post-treatment and acquire images continuously at set intervals (e.g., every 20 minutes for up to 3 hours) [7].

- Data Analysis: Reconstruct 3D surface topography from en face (x-y) cross-sectional data stacks. Analyze morphological parameters such as cell volume, membrane texture (blebbing), and adhesion structure [7].

- Key Observations:

- Apoptotic Cells: Show progressive cell contraction, formation of echinoid spines and membrane blebs, and filopodia reorganization. The cell membrane remains intact throughout [7].

- Necrotic Cells: Exhibit rapid membrane rupture, abrupt loss of adhesion structure, and leakage of intracellular contents, leading to a sudden loss of structural definition [7].

Classical Staining and Microscopy Techniques

Despite technological advances, traditional staining methods combined with microscopy remain a cornerstone for morphological assessment.

- Light Microscopy with H&E Staining:

- Protocol: Fix cells or tissue sections, stain with hematoxylin (nuclei blue) and eosin (cytoplasm pink). Examine under a light microscope [2] [6].

- Observation: Apoptotic cells appear as round/oval masses with dark eosinophilic (pink) cytoplasm and dense purple nuclear chromatin fragments. They often affect single cells or small clusters [2].

- Fluorescence Microscopy with Hoechst/DAPI:

- Protocol: Incubate live or fixed cells with membrane-permeable DNA-binding dyes like Hoechst 33342 (2-5 μg/mL) or DAPI. Examine under a fluorescence microscope with UV excitation [6].

- Observation: Viable nuclei show diffuse, dim staining. Apoptotic nuclei show bright, condensed, and fragmented chromatin, often aggregated at the nuclear periphery [6].

- Electron Microscopy:

- Protocol: Fix cells with glutaraldehyde and osmium tetroxide, dehydrate, embed in resin, section, and stain with heavy metals (e.g., uranyl acetate) [6].

- Observation: Provides the highest resolution view of subcellular changes, such as chromatin margination, intact organelles in apoptosis, and swollen organelles in necrosis [2] [6].

The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow for the morphological assessment of cell death.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Apoptosis and Necrosis Studies

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function / Application | Key Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Doxorubicin [7] | Chemical inducer of intrinsic apoptosis via DNA intercalation and Topoisomerase II inhibition. | Used at ~5 μmol/L for in vitro apoptosis induction in HeLa cells. |

| Ethanol [7] | Chemical inducer of necrosis via protein denaturation and membrane disruption. | High concentrations (e.g., 99%) used for rapid, unregulated cell death. |

| Anti-Fas Antibody [8] | Activator of the extrinsic apoptosis pathway by clustering the Fas death receptor. | Used in Jurkat T-cell models to study receptor-mediated apoptosis. |

| Hoechst 33342 / DAPI [6] | Cell-permeable fluorescent DNA dyes for nuclear staining and visualization of chromatin condensation. | Excitation ~350 nm (UV), Emission ~461 nm (blue). Apoptotic nuclei show bright, condensed fluorescence. |

| Caspase-3 Antibody [5] | Immunodetection of cleaved/active caspase-3, a key executioner protease and gold-standard apoptotic biomarker. | Used in IHC, WB, and IF to confirm apoptosis commitment. |

| BAX Antibody [5] | Detects the pro-apoptotic protein BAX, which translocates to mitochondria during intrinsic apoptosis. | Indicator of mitochondrial pathway engagement. |

| Annexin V Assays | Binds to phosphatidylserine (PS) exposed on the outer leaflet of the apoptotic cell membrane. | Often used in flow cytometry with Propidium Iodide (PI) to distinguish early apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI-) from necrotic (Annexin V+/PI+) cells. |

| Dead Cell Removal Kits [1] | Magnetic or buoyancy-based separation of dead cells (often with compromised membranes) from live cell populations. | Improves purity and accuracy of downstream assays in cell isolation workflows. |

Critical Considerations and the Apoptosis-Necrosis Continuum

While the morphological distinctions between apoptosis and necrosis are foundational, the reality in experimental and pathological contexts is often more complex. Researchers must be aware that:

- The apoptosis-necrosis continuum: The same initial insult can cause apoptosis at low doses and necrosis at high doses [2]. Furthermore, features of both processes can coexist in the same tissue or even the same cell, a phenomenon sometimes called "apoptotic necrosis" or "necrapoptosis" [2] [6].

- Shared biochemical network: Apoptosis and necrosis are now understood to represent morphological expressions of a shared biochemical network. Key factors like the availability of caspases and intracellular ATP can determine the mode of death; for instance, if ATP is depleted during an apoptotic stimulus, the cell may undergo secondary necrosis [2].

- Emerging forms of programmed necrosis: Regulated forms of cell death that morphologically resemble necrosis, such as necroptosis, have been identified. Like apoptosis, it is genetically controlled, but it results in cell swelling and membrane rupture, similar to necrosis [1] [3] [5].

- Cell shrinkage is separable from apoptosis: Intriguing experimental evidence shows that under specific ionic conditions (sodium-substituted medium), cells can undergo all biochemical hallmarks of apoptosis, including caspase activation and DNA fragmentation, without shrinking, and instead swell [8]. This demonstrates that ion fluxes, not shrinkage itself, are critical for the death process.

Cell death is a fundamental biological process, and its accurate characterization is crucial for understanding disease pathogenesis and developing therapeutic strategies. Within this field, the morphological differentiation between apoptosis and necrosis provides critical insights into the mechanism and consequences of cell death. Necrosis is defined as an uncontrolled form of cell death triggered by external factors such as injury, trauma, infection, or toxins, leading to a cascade of distinctive morphological events [9] [10]. In contrast to programmed cell death pathways, necrosis is characterized by its unregulated nature and its tendency to trigger inflammatory responses [11] [10].

This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of the morphological features of necrosis, with a specific focus on swelling, oncosis, and membrane rupture. It is structured within the broader thesis of differentiating apoptosis from necrosis, supplying researchers and drug development professionals with consolidated experimental data, validated protocols, and essential research tools for precise cell death identification.

Core Morphological Features of Necrosis

The progression of necrosis follows a characteristic sequence of events, beginning with cellular swelling and culminating in the complete loss of membrane integrity. The table below summarizes the key morphological stages and their functional consequences.

Table 1: Characteristic Morphological Events in Necrosis

| Morphological Event | Description | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Swelling (Oncosis) | The cytoplasm and mitochondria swell up, leading to cell enlargement [9]. | Disruption of osmotic pressure balance and ion homeostasis [11]. |

| Plasma Membrane Rupture | The cell membrane loses integrity and ruptures (cell lysis) [9] [11]. | Leakage of intracellular contents into the extracellular space [9]. |

| Organelle Swelling | Organelles, including the ER and mitochondria, swell and disintegrate [9] [11]. | Cessation of organelle function and cellular metabolism [9]. |

| Inflammatory Response | Not a morphological feature of the cell per se, but a direct result of the release of cellular debris [11]. | Activation of immune cells, leading to inflammation and potential damage to surrounding tissues [9] [10]. |

The term "oncosis" is used specifically to describe the pre-lethal swelling process that precedes membrane rupture in necrosis [11]. This swelling is driven by the failure of ion pumps in the plasma membrane, leading to an influx of water and electrolytes. The loss of membrane integrity is a hallmark event, distinguishing necrosis from apoptosis, where membrane integrity is typically maintained until the final stages [9].

Objective Morphological Comparison: Necrosis vs. Apoptosis

Accurate differentiation between necrosis and apoptosis is a cornerstone of cell death research. The following table provides a side-by-side comparison of their defining characteristics, based on established experimental observations.

Table 2: Direct Comparison of Necrosis and Apoptosis Morphology

| Feature | Necrosis | Apoptosis |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Process | Accidental, unregulated cell death from external injury [9]. | Programmed, controlled "cellular suicide" [9]. |

| Cell Morphology | Cytoplasm and mitochondria swell; cell undergoes lysis [9]. | Cell shrinks and condenses; cytoplasm dehydrates [9]. |

| Membrane Integrity | Lost; membrane ruptures and becomes highly permeable [9] [11]. | Largely maintained; membrane blebs but does not rupture [9]. |

| Organelle Behavior | Organelles swell and disintegrate [9]. | Organelles remain largely intact and functional until late stages [9]. |

| Fate of Cellular Contents | Released into extracellular space [9]. | Packaged into apoptotic bodies for phagocytosis [9]. |

| Inflammatory Response | Almost always triggered due to leaked contents [9] [11]. | Typically, no inflammation [9]. |

| Scope of Effect | Often affects contiguous groups of cells [9]. | Localized to individual cells [9]. |

The diagrams below visualize the distinct morphological pathways of necrosis and apoptosis, and a typical experimental workflow for their differentiation.

Cell Death Morphology: Necrosis Pathway

Workflow for Differentiating Cell Death

Experimental Data and Methodologies for Necrosis Detection

High-Resolution Imaging of Necrotic Morphology

Advanced label-free imaging techniques like Full-Field Optical Coherence Tomography (FF-OCT) allow for high-resolution, real-time observation of necrotic morphology.

Experimental Protocol [7]:

- Cell Preparation: HeLa cells are cultured as a monolayer in DMEM under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂).

- Necrosis Induction: Cells are treated with 99% ethanol to induce nonspecific, rapid cellular damage leading to necrosis. Ethanol penetrates the lipid bilayer, disrupts membrane integrity, and denatures proteins.

- FF-OCT Imaging: A custom-built time-domain FF-OCT system with a broadband halogen light source is used. Imaging begins immediately post-treatment and continues at 20-minute intervals for up to 180 minutes.

- Data Analysis: 3D surface topography maps are reconstructed from the acquired tomographic image stacks to visualize and quantify morphological changes.

Key Observations [7]: FF-OCT effectively visualized the hallmark features of ethanol-induced necrosis, including rapid membrane rupture, intracellular content leakage, and an abrupt loss of adhesion structures.

Fluorescent Staining and Automated Quantification

Fluorescent staining kits provide a biochemical basis for differentiating cell death states and can be scaled for high-throughput analysis.

Experimental Protocol (Annexin V-CY3TM Kit) [12]:

- Cell Culture and Treatment: HeLa cells are seeded and allowed to adhere for 24 hours. Necrosis is induced, for example, via photodynamic treatment.

- Staining: Cells are simultaneously incubated with two probes: Annexin-Cy3.18 (AnnCy3), which binds to phosphatidylserine on the outer membrane, and 6-Carboxyfluorescein diacetate (6-CFDA), a viability dye hydrolyzed by intracellular esterases in live cells.

- Imaging: Cells are imaged using a confocal microscope with filters set for 6-CF (ex 495/em 520 nm) and AnnCy3 (ex 550/em 570 nm).

- Automated Analysis: The ApoNecV macro for the Fiji platform can automate the quantification. It performs background subtraction and deconvolution before classifying cells based on fluorescence:

- Viable cells: Green fluorescence (6-CF) only.

- Apoptotic cells: Both green (6-CF) and red (AnnCy3) fluorescence.

- Necrotic cells: Red fluorescence (AnnCy3) only, due to loss of membrane integrity and leakage of green 6-CF.

Key Observations [12]: This method reliably distinguishes necrotic cells (red-only signal) based on their compromised membrane, a defining feature absent in early apoptosis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents and tools essential for conducting research on necrotic cell death.

Table 3: Key Reagents for Necrosis and Cell Death Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function and Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Annexin V-CY3TM Apoptosis Detection Kit | A standard kit using Annexin-Cy3 and 6-CFDA to distinguish viable, apoptotic, and necrotic cell populations via fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry [12]. |

| Full-Field Optical Coherence Tomography (FF-OCT) | A label-free, non-invasive imaging technique for high-resolution 3D visualization of dynamic morphological changes like swelling and membrane rupture in single living cells [7]. |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) | A DNA stain that cannot cross intact membranes. It is used to label necrotic cells with compromised membrane integrity, often in conjunction with other markers [13]. |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Assay Kit | A colorimetric assay that measures LDH enzyme released from the cytosol upon plasma membrane rupture, providing a quantitative measure of necrotic cell death [13]. |

| Caspase Inhibitors (e.g., Z-VAD-FMK) | Pan-caspase inhibitors used experimentally to confirm a death process is caspase-independent, helping to rule out apoptosis and suggesting alternative pathways like necrosis [11]. |

| Chemical Inducers (e.g., Ethanol, H₂O₂) | Used to experimentally induce necrotic cell death in vitro. Ethanol (99%) causes rapid membrane damage and protein denaturation [7]. |

The morphological signature of necrosis—characterized by swelling (oncosis), organelle disintegration, and ultimate plasma membrane rupture—serves as a clear and reliable identifier for this inflammatory form of cell death. The experimental data and methodologies detailed in this guide, from high-resolution FF-OCT to accessible fluorescent staining and automated analysis, provide a robust framework for researchers to accurately distinguish necrosis from apoptosis. Mastery of these morphological distinctions and the associated toolkit is indispensable for advancing our understanding of disease mechanisms, assessing the efficacy of therapeutics, and ultimately developing safer and more effective drugs.

The microscopic examination of nuclear morphology remains a cornerstone in the fundamental classification of cell death pathways. Within the context of apoptosis and necrosis research, specific nuclear changes provide critical diagnostic markers that differentiate controlled, programmed cell death from uncontrolled, accidental death [2]. Chromatin condensation is an early and defining event in the process of programmed cell death, or apoptosis, representing an active, energy-dependent process [2]. This condensation progresses to pyknosis, characterized by nuclear shrinkage and hypercondensation of chromatin [14]. In contrast, karyolysis describes the complete dissolution of the nuclear structure and chromatin, typically following a necrotic pathway [15]. The precise identification and differentiation of these nuclear changes are not merely academic; they are essential for researchers and drug development professionals in accurately interpreting cellular responses to toxic insults, chemotherapeutic agents, and other disease-modifying therapies. This guide provides a structured comparison of these nuclear phenomena, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant to modern cell biology research.

Comparative Morphology and Mechanisms

The journey of a dying cell is vividly reflected in the transformation of its nucleus. The distinct morphological pathways observed in apoptosis and necrosis offer a visual language for classifying cell death.

Apoptotic Nuclear Changes: A Controlled Demolition

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is a highly regulated process. Its nuclear changes are orderly and specific [2]:

- Chromatin Condensation and Pyknosis: The process begins with marginalization of chromatin, where it moves to the inner periphery of the nuclear membrane, forming a characteristic ring-like structure [15]. This is followed by pyknosis, the irreversible shrinkage and hypercondensation of the entire nucleus [14]. This stage is mediated by caspases (caspase-3 and -6), which cleave nuclear structural proteins like lamins and activate factors such as Acinus to initiate condensation [14] [15].

- Karyorrhexis: Following pyknosis, the condensed nucleus fragments into discrete particles, a process known as karyorrhexis [14] [2]. These nuclear fragments, along with intact organelles and cytoplasm, are then packaged into apoptotic bodies for efficient phagocytosis by neighboring cells, preventing an inflammatory response [2].

Necrotic Nuclear Changes: A Catastrophic Failure

Necrosis, often resulting from severe cellular injury, follows a more chaotic and disruptive course [16] [2]:

- Pyknosis in Necrosis: While also featuring pyknosis, the mechanism in necrosis differs and is termed anucleolytic pyknosis [14]. It involves cellular swelling, separation of the nuclear membrane from chromatin, and subsequent collapse of both structures. A key regulator is the phosphorylation of the barrier-to-autointegration factor (BAF), which disrupts the tethering of chromatin to the nuclear membrane [14].

- Karyolysis: This is the terminal stage of necrotic nuclear death, characterized by the complete dissolution of nuclear material [15]. The chromatin is degraded and digested, often due to the unspecific action of nucleases, leading to the "fading away" of the nucleus [15]. This occurs concurrently with a loss of plasma membrane integrity, causing the release of intracellular contents and provoking a strong inflammatory reaction [16] [2].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Nuclear Changes in Cell Death

| Feature | Apoptotic Pyknosis | Necrotic Pyknosis | Karyolysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Cell Death Type | Apoptosis (Programmed) [14] | Necrosis (Accidental) [14] | Necrosis (Accidental) [15] |

| Overall Process | Ordered, controlled, and energy-dependent [2] | Disordered, uncontrolled, and passive [2] | Passive dissolution [15] |

| Nuclear Morphology | Chromatin condensation → Nuclear fragmentation (Karyorrhexis) [2] | Nuclear shrinkage → Collapse of nuclear structure [14] | Complete dissolution of the nucleus [15] |

| Key Molecular Regulators | Caspase-3, Caspase-6, Acinus, CAD/DFF40 [14] [15] | Phosphorylated BAF, PLA2, AIF (in some models) [14] [15] | Lysosomal and exogenous nucleases (e.g., from Kupffer cells) [15] |

| Cellular Context | Cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, formation of apoptotic bodies [16] [2] | Cell swelling (oncosis), organelle disruption, membrane rupture [16] [2] | Always follows necrotic pyknosis; occurs in a lytic cellular environment [15] |

| Inflammatory Response | None (anti-inflammatory) [2] | Significant (pro-inflammatory) [16] | Significant (pro-inflammatory) [16] |

Visualizing the Pathways of Nuclear Demise

The following diagram illustrates the sequence of key nuclear events in apoptosis and necrosis, highlighting the divergent paths from initial chromatin condensation to the final states of karyorrhexis or karyolysis.

Key Experimental Models and Data

Translating morphological observations into quantifiable data requires robust experimental models and assays. The following table summarizes key experimental findings that delineate apoptotic and necrotic cell death.

Table 2: Experimental Data Differentiating Apoptosis and Necrosis

| Experimental Model | Treatment / Inducer | Key Nuclear Morphology Observed | Primary Cell Death Type | Supporting Biochemical Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatic Ischemia-Reperfusion (Mouse) [17] | 45 min ischemia, 1-24h reperfusion | Predominant necrosis; TUNEL-positive cells showed karyorrhexis | Necrosis | High plasma ALT, miR-122, FK18, HMGB1; minimal caspase-3 activity and CK18 [17] |

| HepG2 Cell Line [18] | Anti-CD95 Antibody | Chromatin condensation, DNA fragmentation | Apoptosis | Cytochrome c release, caspase activation, specific protein cleavage [18] |

| HepG2 Cell Line [18] | Menadione | No DNA fragmentation | Necrosis | Cytochrome c release but no caspase activation; ATP depletion; inhibition reversed by catalase [18] |

| U251 Cell Line (Real-Time Imaging) [19] | Doxorubicin | Apoptotic morphology with subsequent shift to necrosis | Apoptosis → Secondary Necrosis | Caspase activation (FRET ratio change) followed by loss of FRET probe and mitochondrial fluorescence [19] |

| U251 Cell Line (Real-Time Imaging) [19] | Valinomycin / H₂O₂ | Necrotic morphology without caspase activation | Primary Necrosis | Loss of FRET probe without prior ratio change; retention of mitochondrial fluorescence [19] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Real-Time Discrimination

A sophisticated live-cell imaging method for distinguishing apoptosis and necrosis at a single-cell level is described by [19]. The protocol can be summarized as follows:

Cell Line Engineering: Stable expression of two genetically encoded probes in the target cell line (e.g., neuroblastoma U251 cells):

- A FRET-based caspase sensor (ECFP and EYFP linked by a DEVD caspase-cleavable sequence).

- A non-soluble fluorescent marker targeted to mitochondria (e.g., Mito-DsRed).

Treatment and Imaging: Cells are exposed to death-inducing stimuli (e.g., doxorubicin for apoptosis, H₂O₂ for necrosis) and subjected to real-time, time-lapse imaging using wide-field fluorescence or confocal microscopy.

Quantitative Discrimination and Data Analysis:

- Live Cells: Exhibit intact FRET probe (no ratio change) and retained mitochondrial red fluorescence.

- Apoptotic Cells: Show caspase activation, visualized by a loss of FRET (increase in ECFP/EYFP ratio), while retaining mitochondrial DsRed fluorescence.

- Necrotic Cells: Lose the soluble cytosolic FRET probe due to membrane permeabilization (no FRET ratio change) but continue to retain the mitochondrial DsRed fluorescence for a prolonged period.

This method allows for the sensitive and confirmatory real-time quantification of both primary necrosis and secondary necrosis (the lytic phase following apoptosis).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Cell Death Research

The following table catalogs key reagents and their applications in studying nuclear changes and cell death mechanisms.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Cell Death Studies

| Reagent / Assay | Function / Target | Application in Cell Death Research |

|---|---|---|

| Caspase-3 Antibody [20] | Detects activated/cleaved caspase-3 | Key biomarker for identifying apoptotic cells via IHC/IF; gold standard for apoptosis confirmation [3] [20]. |

| BAX Antibody [20] | Detects conformational change in BAX protein | Marker for intrinsic apoptosis pathway activation; indicates mitochondrial membrane pore formation [20]. |

| TUNEL Assay [14] [17] | Labels DNA strand breaks (3'-OH ends) | Detects DNA fragmentation. Note: Can be positive in both apoptosis and necrosis; requires morphological correlation [17]. |

| Annexin V / Propidium Iodide (PI) [19] | Binds phosphatidylserine (PS) / intercalates into DNA | Flow cytometry assay to distinguish early apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI-), late apoptotic/necrotic (Annexin V+/PI+), and necrotic (Annexin V-/PI+) cells. |

| Fixable Viability Dyes [16] | Covalently bind amine groups in dead cells | Flow cytometry-based dead cell removal; distinguishes cells based on membrane integrity. |

| Z-VD-fmk (Pan-Caspase Inhibitor) [17] | Irreversibly inhibits caspase activity | Used to confirm caspase-dependent apoptosis; can shift cell fate to necroptosis/necrosis [17] [18]. |

| AC-DEVD-AMC Fluorogenic Substrate [17] | Caspase-3/7 substrate | Measures caspase-3 activity in cell lysates or plasma; release of fluorescent AMC upon cleavage indicates apoptosis [17]. |

| Caspase Sensor Stable Cell Line [19] | FRET-based probe for caspase activation | Enables real-time, live-cell imaging and quantification of apoptosis as described in the experimental protocol [19]. |

Visualizing the Experimental Workflow

The following diagram outlines the logical workflow for designing an experiment to discriminate between apoptotic and necrotic cell death, integrating the reagents and methods from the toolkit.

Within the broader thesis of morphological feature specificity for apoptosis versus necrosis, the nuclear changes of pyknosis and karyolysis serve as fundamental, histologically accessible endpoints. While pyknosis can initiate both apoptotic and necrotic pathways, its context—preceding either organized karyorrhexis or catastrophic karyolysis—defines the ultimate nature of cell death. The experimental data and methodologies detailed herein provide a framework for researchers to move beyond simple observation to mechanistic insight. The choice of assay, from classic biomarker detection to advanced real-time imaging, depends on the specific research question, whether it involves screening compound toxicity, elucidating death signaling pathways, or characterizing novel cell death modalities. A precise understanding of these nuclear events remains indispensable for accurate interpretation of cellular fate in disease models and therapeutic interventions.

The integrity of the plasma membrane serves as a fundamental distinguishing feature between the two primary forms of cell death, apoptosis and necrosis. This characteristic not only defines their contrasting morphologies but also dictates their physiological consequences, particularly concerning inflammatory responses. The following table summarizes the core differences.

| Feature | Apoptosis | Necrosis (Accidental) |

|---|---|---|

| General Type | Regulated, Programmed Cell Death (RCD) [21] [22] | Accidental Cell Death (ACD) [21] [22] |

| Plasma Membrane Integrity | Maintained until late stages [23] [24] | Rapidly lost [23] [22] |

| Membrane Phenomena | Blebbing and formation of apoptotic bodies [23] [24] | Swelling and rupture (oncosis) [23] [22] |

| Key Process | Phosphatidylserine (PS) externalization as an "eat-me" signal [24] [3] | Non-selective release of intracellular contents [23] |

| Inflammatory Response | Typically non-inflammatory [23] [24] | Strongly pro-inflammatory [23] [24] |

| Primary Inducers | Physiological signals, developmental cues, mild damage [23] [22] | Extreme physical/chemical injury, toxins, ischemia [23] [25] |

Membrane Integrity: The Core Distinction

Apoptosis: A Sealed Demise

In apoptosis, the plasma membrane undergoes a carefully orchestrated transformation without immediately losing its role as a selective barrier. The cell exhibits membrane blebbing—the formation of outward bulges—driven by caspase-3-mediated activation of the ROCK1 kinase, which causes actomyosin contraction [24]. Crucially, the membrane's integrity is preserved during this blebbing [23]. A key biochemical event is the externalization of phosphatidylserine (PS), a phospholipid normally confined to the inner leaflet of the membrane. This surface exposure of PS acts as a critical "eat-me" signal for phagocytes, facilitating the prompt engulfment and disposal of the cell corpse without content leakage [24] [3]. Ultimately, the cell fragments into membrane-bound apoptotic bodies, which safely package cellular contents for phagocytosis [23] [24].

Necrosis: Loss of Barrier Function

Necrosis, in its classical accidental form, is characterized by an uncontrolled loss of plasma membrane integrity [22]. This failure of the barrier function is often preceded by cellular and organelle swelling (oncosis) [22]. The subsequent rupture leads to the non-selective release of intracellular components, such as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), and other damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) into the extracellular space [23] [24]. This unregulated spillage is a potent trigger for inflammation and immune cell recruitment, distinguishing it sharply from the typically non-inflammatory nature of apoptosis [23].

The diagram below illustrates the key morphological differences in the plasma membrane during each process.

Experimental Assessment of Membrane Integrity

Researchers employ specific reagents and assays to differentiate between apoptotic and necrotic cells based on membrane status. The cornerstone of this assessment is the differential permeability of fluorescent dyes.

Key Assays and Dye Permeability

A standard flow cytometry assay uses Annexin V in conjunction with membrane-impermeable DNA-binding dyes like Propidium Iodide (PI) or 7-AAD [26] [27].

- Annexin V+ / PI-: Early apoptotic cell (intact membrane, PS exposed).

- Annexin V+ / PI+: Late apoptotic or necrotic cell (compromised membrane).

- Annexin V- / PI+: Necrotic cell (membrane ruptured, no PS exposure).

Advanced research investigates specific pore-forming proteins. For example, during apoptosis-driven secondary necrosis, Gasdermin E (GSDME) can form pores in the plasma membrane. The influx and efflux of fluorescently-labeled dextrans of varying molecular weights can be monitored to characterize the functional size of these pores [28]. Dye choice is critical, as some, like YO-PRO-1 and TO-PRO-3, can enter early apoptotic cells via pannexin channels, complicating the interpretation of membrane integrity [26]. SYTOX dyes are often preferred for late-stage death as they are not associated with this early mechanism [26].

The experimental workflow for a basic membrane integrity assay is outlined below.

Quantitative Data from Experimental Models

The following table compiles key experimental findings on membrane permeability from selected studies.

| Experimental Model / Assay | Key Readout | Apoptosis Findings | Necrosis Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S49 Lymphoma Cells(Propidium Iodide Uptake) | Modest, gradual PI permeability | Yes, during early apoptosis | N/D | [27] |

| L929sAhFas Cells(Dextran Influx/Efflux) | Permeability to macromolecules | GSDME-dependent dextran influx during secondary necrosis | N/D | [28] |

| General Flow Cytometry(Annexin V/PI Staining) | Phosphatidylserine exposure & membrane integrity | Annexin V+ / PI- (early stage) | Annexin V- / PI+ | [26] [22] |

| General Morphology | Release of intracellular contents | Contents isolated in apoptotic bodies | Uncontrolled release of DAMPs | [23] [24] |

Underlying Signaling Pathways

The difference in membrane fate is determined by upstream molecular events.

Apoptosis: Caspase-Driven Regulation

Apoptosis proceeds via the extrinsic (death receptor) or intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathways, converging on the activation of caspase-3 [22] [3]. Caspase-3 cleaves specific substrates to orchestrate the disciplined dismantling of the cell:

- Cleavage of ROCK1: Triggers actomyosin contraction and membrane blebbing without immediate rupture [24].

- Externalization of Phosphatidylserine: Promotes immunologically silent phagocytosis [24].

- Cleavage of Gelsolin: Mediates disassembly of the actin cytoskeleton [24].

Necrosis and Programmed Necrosis: Direct Membrane Perforation

While accidental necrosis involves unregulated physical rupture, regulated forms like necroptosis and pyroptosis directly target the membrane.

- Necroptosis: Upon activation, the kinases RIPK1 and RIPK3 phosphorylate the pseudokinase MLKL. Phosphorylated MLKL oligomerizes and translocates to the plasma membrane, directly disrupting its integrity and causing lytic cell death [22].

- Pyroptosis: Inflammatory caspases (caspase-1/4/5) cleave Gasdermin D (GSDMD). Its N-terminal fragment forms large pores in the plasma membrane, leading to ion dysregulation, cell swelling, and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [24] [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following reagents are essential for investigating plasma membrane integrity in cell death.

| Reagent / Assay | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Annexin V (conjugated to fluorophores) | Detects phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, a hallmark of early apoptosis. | Requires calcium-containing buffer. Alone, it cannot distinguish between apoptotic and necrotic cells. |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) / 7-AAD | Membrane-impermeant DNA dyes that stain nuclei only in cells with compromised plasma membranes. | Used to identify late apoptotic and necrotic cells. Can be used in combination with Annexin V. |

| SYTOX Blue / Green | High-affinity, membrane-impermeant nucleic acid stains for identifying dead cells. | Provides a strong signal-to-noise ratio; not associated with early entry via pannexin channels [26]. |

| Antibodies against Cleaved Caspase-3 | Confirm the activation of the key executioner caspase in apoptosis. | Validates that cell death is occurring via the apoptotic pathway. |

| Antibodies against p-MLKL (Phospho-Mixed Lineage Kinase Domain-Like) | Detects the active form of MLKL, a key effector of necroptosis. | Specific marker for the regulated necroptotic pathway. |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Release Assay | Measures the activity of LDH enzyme released from the cytosol upon membrane rupture. | A standard colorimetric assay for quantifying cytotoxicity and lytic cell death. |

The integrity of the plasma membrane provides a clear and functionally decisive criterion for distinguishing apoptosis from necrosis. Apoptosis is a sealed, regulated process where membrane integrity is maintained to prevent inflammation, while necrosis is defined by a loss of membrane integrity that precipitates a potent inflammatory response. Advanced research continues to reveal the complex regulation behind these events, including the role of pore-forming proteins like Gasdermins and MLKL in programmed lytic cell death. A solid understanding of these principles and the associated experimental tools is indispensable for accurate interpretation of cell death phenomena in research and drug development.

Cell death is a fundamental physiological process, and its mode carries profound implications for organismal health. Among the various forms of cell death, apoptosis and necrosis represent two distinct mechanisms with opposing inflammatory outcomes. Apoptosis, known as programmed cell death, is a genetically regulated process that eliminates unwanted or damaged cells in a controlled manner without eliciting an inflammatory response, making it immunologically "silent" [30] [31]. In contrast, necrosis has traditionally been viewed as an unregulated, catastrophic form of cell death resulting from overwhelming external damage, characterized by cellular swelling and membrane rupture that leads to the release of intracellular contents and triggers a significant inflammatory reaction—rightfully earning its "alarming" designation [32] [33]. This fundamental difference in inflammatory potential stems from their unique morphological features, biochemical pathways, and physiological contexts, which we will explore through comparative morphological analysis, molecular mechanisms, and experimental approaches.

Morphological and Biochemical Hallmarks: A Comparative Analysis

The distinct inflammatory outcomes of apoptosis and necrosis are direct consequences of their structural disintegration processes, which can be observed through both microscopic and biochemical analyses.

Characteristic Features of Apoptosis

Apoptosis demonstrates a highly orchestrated series of morphological events that facilitate clean cell removal. The process initiates with cell shrinkage and loss of specialized cell-to-cell contacts [3] [33]. The nucleus undergoes characteristic chromatin condensation (pyknosis) followed by nuclear fragmentation (karyorrhexis) [30]. The cell membrane begins to bleb and form apoptotic bodies—small, membrane-bound vesicles containing intact organelles and nuclear fragments [3] [33]. Critically, the plasma membrane remains intact throughout this process, preventing the release of cellular contents [31]. Biochemically, apoptosis features phosphatidylserine externalization on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, which serves as an "eat me" signal for phagocytes [3] [33]. It also involves caspase activation and DNA cleavage into specific, regularly sized fragments (DNA laddering) [33] [30].

Characteristic Features of Necrosis

Necrosis presents a drastically different morphological pattern characterized by catastrophic cellular disintegration. The process begins with cell and organelle swelling (oncosis), including dilation of the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria [32] [33]. This is followed by plasma membrane rupture and subsequent release of intracellular contents—including organelles, proteins, and DNA fragments—into the extracellular space [32] [33]. The nucleus undergoes either dissolution (karyolysis) or irregular fragmentation without the organized pattern seen in apoptosis [32]. Unlike apoptosis, necrosis demonstrates random DNA degradation without specific fragment sizes, resulting in a "smear" pattern rather than a DNA ladder [33]. This loss of membrane integrity and release of cellular components directly triggers inflammatory responses [32] [33].

Table 1: Comparative Morphological and Biochemical Features of Apoptosis and Necrosis

| Feature | Apoptosis | Necrosis |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Size | Shrinkage | Swelling (oncosis) |

| Plasma Membrane | Intact with blebbing and apoptotic body formation; phosphatidylserine exposure | Rupture and disintegration |

| Organelles | Generally intact | Swelling and disruption |

| Nucleus | Chromatin condensation, pyknosis, karyorrhexis | Karyolysis, irregular fragmentation |

| DNA Fragmentation | Internucleosomal cleavage (DNA laddering) | Random degradation (DNA smear) |

| Inflammatory Response | None ("silent") | Significant ("alarming") |

| Energy Requirement | ATP-dependent | ATP-independent |

| Phagocytic Recognition | Efficient by neighboring cells | Inefficient; requires professional phagocytes |

Molecular Mechanisms: Signaling Pathway Dissection

The divergent inflammatory outcomes of apoptosis and necrosis are determined by their distinct molecular circuitry, which governs the cell death execution process.

The Apoptotic Signaling Cascade

Apoptosis proceeds through two main pathways that converge on caspase activation. The extrinsic pathway initiates through extracellular death ligands (e.g., FasL, TNF-α) binding to cell surface death receptors, leading to the formation of the Death-Inducing Signaling Complex (DISC) and activation of initiator caspase-8 [3] [30] [31]. The intrinsic pathway triggers in response to internal cellular damage (e.g., DNA damage, oxidative stress) through mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), controlled by BCL-2 family proteins, resulting in cytochrome c release and formation of the apoptosome, which activates caspase-9 [3] [30] [31]. Both pathways converge to activate executioner caspases (caspase-3, -6, -7) that systematically cleave cellular substrates, leading to the characteristic morphological changes while maintaining membrane integrity [3] [30].

The Necrotic Signaling Cascade

While traditionally considered unregulated, certain forms of necrosis—specifically necroptosis—follow defined molecular pathways. Necroptosis can be initiated by death receptor activation (e.g., TNFR1) under conditions of caspase inhibition [3] [34]. This leads to the formation of a complex containing RIPK1 and RIPK3, known as the necrosome [34]. The necrosome phosphorylates the effector protein MLKL, causing it to oligomerize and translocate to the plasma membrane [33] [34]. MLKL oligomers form pores in the plasma membrane or activate ion channels, leading to membrane rupture, ion imbalance, and cellular swelling [34]. The subsequent release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs)—including HMGB1, ATP, and DNA fragments—activates immune cells and initiates robust inflammatory responses [32] [34].

Experimental Approaches: Discriminating Cell Death Modalities

Accurately distinguishing between apoptosis and necrosis is crucial for both research and clinical applications. Several well-established methodologies enable researchers to differentiate these processes based on their characteristic features.

Imaging-Based Discrimination Techniques

Advanced imaging technologies provide powerful tools for visualizing the distinct morphological changes associated with each cell death type. Full-field optical coherence tomography (FF-OCT) enables label-free, high-resolution visualization of apoptotic cells showing characteristic echinoid spine formation, cell contraction, membrane blebbing, and filopodia reorganization, while necrotic cells exhibit rapid membrane rupture, intracellular content leakage, and abrupt loss of adhesion structures [7]. Quantitative phase microscopy (QPM) allows non-invasive imaging of living cells by measuring phase shifts in transmitted light to map density distribution and refractive index variations within intracellular structures, revealing subtle structural differences between apoptotic and necrotic cells [7]. Live-cell imaging using FRET-based caspase sensors combined with organelle-targeted fluorescent proteins (e.g., Mito-DsRed) enables real-time discrimination at single-cell resolution—apoptotic cells show caspase activation (FRET loss) while retaining mitochondrial fluorescence, whereas necrotic cells lose the soluble FRET probe without caspase activation while maintaining organelle fluorescence [35].

Biochemical and Histological Assays

Multiple biochemical approaches capitalize on the distinct molecular events characterizing each cell death pathway. Annexin V/PI staining distinguishes early apoptotic cells (Annexin V+/PI-) with exposed phosphatidylserine but intact membranes from necrotic cells (Annexin V+/PI+) with compromised membrane integrity [17] [33]. Caspase activity assays using fluorogenic substrates (e.g., Ac-DEVD-AMC) or cleavage detection by Western blot specifically identify apoptotic cells [17] [30]. DNA fragmentation analysis through DNA laddering detection or TUNEL staining identifies apoptotic cells, though TUNEL can also stain necrotic cells with nonspecific DNA damage, requiring careful interpretation [17] [30]. Histological evaluation of tissue sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) reveals characteristic patterns—apoptosis shows single-cell involvement with condensed nuclei and apoptotic bodies, while necrosis displays contiguous cells with swelling and loss of architecture [32] [17].

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Discriminating Apoptosis and Necrosis

| Method Category | Specific Assay | Apoptosis Detection | Necrosis Detection | Key Differentiating Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging | FF-OCT | Cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing | Membrane rupture, content leakage | Membrane integrity during death process |

| Live-Cell Imaging | FRET-based caspase sensors + Mito-DsRed | Caspase activation with organelle retention | Loss of soluble probes with organelle retention | Caspase activation vs. membrane permeability |

| Flow Cytometry | Annexin V/PI staining | Annexin V+/PI- (early) | Annexin V+/PI+ | Membrane integrity with phosphatidylserine exposure |

| Biochemical | Caspase activity assays | Caspase-3/7, -8, or -9 activation | No caspase activation | Presence of specific protease activity |

| Molecular | DNA fragmentation analysis | DNA laddering pattern | Random DNA smear | Pattern of DNA degradation |

| Histological | H&E staining | Single cells, condensed nuclei, apoptotic bodies | Cell groups, swelling, architecture loss | Tissue pattern and nuclear morphology |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

This section details crucial laboratory reagents and methodologies employed in the key studies cited throughout this article, providing researchers with practical experimental guidance.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for Cell Death Studies

| Reagent/Method | Application | Experimental Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doxorubicin | Apoptosis induction | Chemotherapeutic agent that intercalates into DNA, causing double-strand breaks and activating p53 pathway [7] [35] | Typically used at 5 μmol/L concentration; effective in rapidly proliferating cells |

| Ethanol | Necrosis induction | Lipid solvent that disrupts membrane integrity and denatures proteins at high concentrations [7] | 99% concentration induces rapid necrotic death; effects are concentration-dependent |

| Z-VD-fmk | Caspase inhibition | Pan-caspase inhibitor used to distinguish caspase-dependent and independent death pathways [17] | Can shift cell fate from apoptosis to necroptosis when death receptors are engaged |

| Recombinant TNF-α | Death receptor activation | Cytokine that activates TNFR1, inducing either apoptosis or necroptosis depending on cellular context [34] | Outcome depends on downstream signaling modifiers (caspase activity, NF-κB activation) |

| Annexin V-FITC/PI | Flow cytometry detection | Dual staining distinguishes early apoptotic (FITC+/PI-) from necrotic (FITC+/PI+) cells [33] | Requires careful timing as late apoptotic cells become PI+ (secondary necrosis) |

| TUNEL Assay | DNA fragmentation detection | Labels DNA strand breaks in situ; identifies apoptotic and necrotic cells [17] [36] | Not specific for apoptosis; necrotic cells with random DNA damage also stain positive |

| Caspase-3 Antibody | Immunodetection | Detects caspase-3 cleavage/activation as specific apoptosis marker [33] | Cleaved caspase-3 is definitive apoptosis indicator; multiple commercial antibodies available |

| FRET-based Caspase Sensor | Live-cell imaging | Genetically encoded probe (ECFP-DEVD-EYFP) shows caspase activation by FRET loss [35] | Enables real-time, single-cell analysis of caspase activation dynamics |

The fundamental distinction between the "silent" nature of apoptosis and the "alarming" character of necrosis has profound implications for both physiological homeostasis and pathological conditions. Apoptosis serves as the primary mechanism for programmed cell elimination during development, tissue remodeling, and immune system regulation without provoking inflammation or tissue damage [30] [31]. In contrast, necrosis typically occurs under pathological conditions—such as ischemia, trauma, or infection—where it not only causes local tissue damage but also amplifies inflammatory responses through DAMP release [32] [34]. Understanding these differential inflammatory outcomes provides critical insights for therapeutic development, particularly in oncology where promoting apoptosis in cancer cells represents a key treatment strategy, while minimizing necrosis-associated inflammation can improve therapeutic outcomes [31] [35]. Future research continues to explore the complex interplay between these cell death pathways and their modulation for therapeutic benefit across diverse disease contexts.

Morphological and Functional Distinction: Necroptosis vs. Apoptosis

The classical view of cell death delineated a clear boundary: apoptosis was a programmed, controlled process, while necrosis was considered an unregulated, accidental death resulting from extreme injury or stress [37] [38]. The discovery of necroptosis fundamentally challenged this dichotomy, revealing a form of cell death that is genetically programmed yet exhibits a necrotic morphology [39] [40].

The table below provides a detailed comparison of the core characteristics of apoptosis and necroptosis, highlighting the distinct profile of necroptosis as a regulated pathway with inflammatory consequences.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Apoptosis and Necroptosis

| Feature | Apoptosis | Necroptosis |

|---|---|---|

| Regulation | Programmed, highly regulated [38] | Programmed and regulated [39] [40] |

| Morphology | Cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, membrane blebbing, formation of apoptotic bodies [38] [41] | Cell and organelle swelling, plasma membrane rupture [42] [39] [40] |

| Membrane Integrity | Maintained until late stages (blebbing) [38] [41] | Lost, leading to permeabilization and rupture [42] [39] |

| Inflammatory Response | Typically none (non-immunogenic) [38] [41] | Strong, pro-inflammatory response [39] [40] [43] |

| Key Mediators | Caspases (e.g., Caspase-3, -8) [38] [41] [44] | RIPK1, RIPK3, MLKL [37] [42] [39] |

| Energy Dependence | ATP-dependent [41] | ATP-independent [41] |

| Primary Physiological Role | Developmental programming, tissue homeostasis [38] [41] | Host defense against pathogens, alternative death pathway when apoptosis is blocked [39] [41] |

Molecular Mechanisms and Key Signaling Pathways

Necroptosis is initiated by specific stimuli, most notably Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF-α) binding to its receptor TNFR1, but also by Toll-like receptors (TLR3, TLR4), and viral sensors [39] [40]. The core regulatory machinery involves a cascade of protein interactions and phosphorylation events.

The following diagram illustrates the critical molecular switch at the heart of the TNF-α-induced necroptotic pathway.

Diagram Title: Molecular Switch Between Apoptosis and Necroptosis

Pathway Breakdown:

- Initiation: TNF-α binding to TNFR1 triggers the formation of a membrane-associated complex (Complex I) containing TRADD, TRAF2/5, and cellular Inhibitor of Apoptosis Proteins (cIAP1/2). Within this complex, RIPK1 is polyubiquitinated, leading to the activation of pro-survival NF-κB signaling [39] [40].

- The Switch: Deubiquitination of RIPK1 (e.g., by the enzyme CYLD) prompts the formation of a cytoplasmic complex. This complex includes FADD and procaspase-8. Active caspase-8 cleaves and inactivates RIPK1 and RIPK3, promoting apoptosis. However, when caspase-8 activity is inhibited—a common strategy employed by viruses or cancer cells—the cell defaults to necroptosis [39] [40].

- Necrosome Formation: In the absence of caspase-8 activity, RIPK1 and RIPK3 interact through their RIP Homotypic Interaction Motif (RHIM) domains, forming a structure known as the necrosome. This leads to auto- and trans-phosphorylation of RIPK3 [42] [39].

- Execution: Phosphorylated RIPK3 then recruits and phosphorylates the key executioner protein, Mixed Lineage Kinase Domain-Like (MLKL). This causes MLKL to oligomerize and translocate to the plasma membrane, where it integrates and forms pores, leading to membrane rupture, release of cellular contents, and the characteristic inflammatory response [42] [39] [40].

Experimental Approaches for Studying Necroptosis

Dissecting the necroptotic pathway relies on a combination of genetic, pharmacological, and biochemical techniques. The table below outlines key reagents and methodologies used to probe this form of cell death experimentally.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Necroptosis Investigation

| Research Tool | Type | Mechanism of Action / Function | Key Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Necrostatin-1 (Nec-1) [37] | Small-molecule inhibitor | Potent and specific inhibitor of RIPK1 kinase activity. | Used to confirm RIPK1-dependent necroptosis in vitro and in vivo. A cornerstone tool for establishing the regulated nature of the process [37]. |

| GSK'872 / GSK'843 [37] | Small-molecule inhibitor | Selective inhibitor of RIPK3 kinase activity. | Used to inhibit downstream signaling from RIPK3, distinguishing RIPK1-dependent from RIPK1-independent necroptosis pathways [37]. |

| Necrosulfonamide [37] | Small-molecule inhibitor | Directly targets and inhibits human MLKL. | Blocks the final execution step of necroptosis, preventing plasma membrane rupture. Used to confirm MLKL's role as the effector protein [37]. |

| z-VAD-FMK [39] | Pan-caspase inhibitor | Irreversibly inhibits caspase activity. | Used experimentally to block apoptosis and create conditions permissive for necroptosis induction (e.g., in combination with TNF-α) [39]. |

| siRNA/shRNA | Genetic tool | Knocks down expression of specific target genes (e.g., RIPK1, RIPK3, MLKL). | Validates the essential role of specific proteins in the necroptotic pathway in a genetic loss-of-function context [42]. |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies (e.g., anti-pMLKL) | Immunological reagent | Detects the phosphorylated, active form of MLKL. | Used in Western blotting and immunohistochemistry as a definitive biochemical marker for ongoing necroptosis [42]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Inducing and Confirming Necroptosis in Vitro

A standard protocol for inducing and validating necroptosis in cell culture (e.g., in mouse fibroblast L929 or HT-29 cells) involves the following steps [37] [39]:

Stimulation: Treat cells with a combination of:

- TNF-α (e.g., 20-50 ng/mL): The primary death ligand.

- z-VAD-FMK (e.g., 20 µM): A pan-caspase inhibitor to block apoptosis.

- Smac mimetic (e.g., 100 nM): To degrade cIAP1/2 and promote complex II formation. This combination is often referred to as TSZ treatment.

Inhibition Control: Include control groups where the TSZ treatment is supplemented with specific inhibitors:

- Necrostatin-1 (10-30 µM) to inhibit RIPK1.

- GSK'872 (1 µM) to inhibit RIPK3. Cell viability in these groups, measured 16-24 hours post-treatment, should be significantly higher than in the TSZ-only group.

Cell Death Assessment:

- Viability Assays: Quantify cell death using methods like propidium iodide (PI) uptake followed by flow cytometry, or MTT/XTT assays. Necroptotic cells, with their compromised membranes, will be PI-positive.

- Morphological Analysis: Observe cells by phase-contrast microscopy for hallmarks of necrosis: swelling, plasma membrane blebbing (without fragmentation into apoptotic bodies), and eventual lysis.

Biochemical Confirmation:

- Western Blotting: Analyze cell lysates for key signaling events.

- Detect phosphorylation of RIPK3 and MLKL.

- Monitor cleavage of caspases (e.g., Caspase-3, -8) to confirm apoptosis inhibition by z-VAD.

- Western Blotting: Analyze cell lysates for key signaling events.

The following flowchart summarizes this multi-faceted experimental approach.

Diagram Title: Workflow for Necroptosis Induction and Validation

Necroptosis in Disease and Therapy: A Double-Edged Sword

The potent immunogenicity of necroptosis underpins its dual role in disease, functioning as both a protective mechanism and a pathogenic driver.

- Anti-Tumor Potential: Necroptosis induction is a promising strategy for overcoming apoptosis resistance in cancers. For instance, the prognostic signature of necroptosis-related genes like

CAMK2A,CHMP4C, andPYGBin Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma (LUSC) highlights its clinical relevance [42]. Furthermore, nanomaterials are being engineered to specifically trigger necroptosis in tumor cells, offering a novel approach to cancer therapy [40]. - Pathological Inflammation: Conversely, aberrant necroptosis is implicated in the pathology of numerous inflammatory and degenerative diseases. The uncontrolled release of DAMPs can drive damaging inflammation in conditions such as ischemia-reperfusion injury (e.g., in heart attack and stroke), inflammatory bowel disease, and neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer's and Huntington's disease [37] [39] [43]. In these contexts, pharmacological inhibition of key nodes in the pathway (e.g., with Necrostatin-1) has shown protective effects in preclinical models [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Necroptosis Research

The following table consolidates essential tools that form the backbone of experimental necroptosis research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Necroptosis Investigation

| Category | Reagent Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Inducers | TNF-α, TSZ combination, LPS + z-VAD, Poly(I:C) [37] [39] | Activate death receptors or TLRs to initiate the necroptotic signaling cascade. |

| RIPK1 Inhibitors | Necrostatin-1, Nec-1s, PN10 [37] | Specifically block RIPK1 kinase activity, used to confirm upstream involvement of RIPK1. |

| RIPK3 Inhibitors | GSK'840, GSK'843, GSK'872 [37] | Specifically block RIPK3 kinase activity, used to inhibit the core necrosome complex. |

| MLKL Inhibitors | Necrosulfonamide (human-specific) [37] | Blocks the pore-forming activity of MLKL, preventing the final step of membrane disruption. |

| Caspase Inhibitors | z-VAD-FMK, Q-VD-OPh [39] | Pan-caspase inhibitors used to create permissive conditions for necroptosis by blocking apoptosis. |

| Detection Tools | Anti-pMLKL antibodies, Propidium Iodide (PI), Viability dyes [42] | Used to biochemically confirm pathway activation (pMLKL) and assess loss of membrane integrity (PI). |

Beyond the Microscope: Advanced Techniques for Visualizing Cell Death Morphology

In biomedical research, particularly in drug development and toxicology, the ability to distinguish between apoptosis and necrosis is crucial. These two modes of cell death have distinct morphological features and physiological implications. Apoptosis is a genetically regulated, programmed process essential for development and tissue homeostasis, while necrosis represents an uncontrolled, pathological response to severe injury [45] [7]. Traditional methods for distinguishing these pathways often rely on fluorescent staining, which can alter native cell biology and preclude long-term live-cell imaging. Full-field optical coherence tomography (FF-OCT) has emerged as a powerful label-free imaging technique that enables non-invasive, high-resolution visualization of dynamic cellular processes without requiring contrast agents or sample fixation [45] [46] [7].

FF-OCT represents a significant advancement over conventional OCT by illuminating and detecting the entire field of view simultaneously using a two-dimensional camera, enabling rapid, en face imaging with isotropic resolution approaching 1 μm [46]. This technical approach provides several advantages for live-cell imaging: minimal photodamage, continuous monitoring of the same sample over extended periods, and the ability to reconstruct three-dimensional cellular architectures from optical sections [47]. When applied to the study of cell death mechanisms, FF-OCT captures the distinctive, dynamic morphological changes that characterize apoptotic and necrotic pathways, providing researchers with a powerful tool for drug toxicity testing, anticancer therapy evaluation, and regenerative medicine applications [45] [7].

Technical Foundations of FF-OCT for Live-Cell Imaging

Basic Principles and System Configurations

FF-OCT operates on the principles of low-coherence interferometry, typically implemented in a Linnik microscope configuration with identical high-numerical-aperture objectives in both reference and sample arms [45] [48]. A spatially incoherent light source, such as a halogen lamp or light-emitting diode (LED), provides illumination, with the broad spectral bandwidth determining the axial resolution of the system [48] [7]. When the optical path lengths of the reference and sample arms are matched within the coherence length of the source, interference occurs between light back-reflected from the reference mirror and back-scattered from intracellular structures within the sample [49] [48].

The resulting interferometric signals are detected simultaneously across the entire field of view using a high-speed megapixel camera [48]. In traditional FF-OCT systems, depth sectioning is achieved by phase-shifting the reference mirror using a piezoelectric transducer and processing multiple interferograms to reconstruct en face optical sections [50] [7]. More recent innovations include continuous-scanning FF-OCT, which eliminates the need for piezoelectric modulation by continuously translating the sample axially while acquiring images, then applying Fourier analysis to the temporal signal at each pixel to extract depth-resolved information [50]. This approach simplifies system design and enables faster volumetric imaging—typically acquiring a 400 μm volume within 100 seconds [50].

Dynamic FF-OCT and Metabolic Contrast

A significant advancement in FF-OCT technology is the development of dynamic FF-OCT (D-FFOCT), which analyzes temporal fluctuations in the interferometric signal to generate contrast based on intracellular motility and metabolic activity [46] [47] [48]. In D-FFOCT, a time series of interferograms (typically 500 images at 100 Hz) is recorded at each imaging position, capturing signal variations induced by natural dynamics within biological samples [48]. The frequency characteristics of these temporal variations are then computed through power spectral density analysis and color-coded, with transitions from red to blue indicating increasing signal variation speed, and brightness corresponding to variation magnitude [48].

This dynamic contrast mechanism is particularly valuable for distinguishing different cellular states and activities. Metabolic processes such as mitochondrial dynamics, vesicular transport, and membrane fluctuations generate distinctive signal patterns that can be quantified using algorithms including standard deviation (STD), logarithmic intensity variation (LIV), and OCT correlation decay speed (OCDS) analysis [46]. The integration of both structural and functional imaging capabilities within a single platform makes dual-mode FF-OCT systems particularly powerful for comprehensive cell state assessment, especially in the context of differentiating apoptosis from necrosis [48].

Experimental Methodology for Cell Death Imaging

Cell Preparation and Death Induction Protocols

To investigate apoptotic and necrotic pathways using FF-OCT, researchers typically employ established cell lines such as HeLa (human cervical cancer cells) cultured under standard conditions [45] [7]. For apoptosis induction, doxorubicin—an anthracycline chemotherapeutic agent that intercalates into DNA and inhibits topoisomerase II—is added to the culture medium at a final concentration of 5 μmol/L [45] [7]. This treatment triggers intracellular injury responses, including activation of the p53 pathway and increased reactive oxygen species production, leading to programmed cell death. For necrosis induction, cells are treated with 99% ethanol, which causes nonspecific cellular damage through membrane disruption, protein denaturation, and loss of ion homeostasis, resulting in uncontrolled cell death [45] [7]. FF-OCT imaging typically begins immediately after drug administration and continues at regular intervals (e.g., every 20 minutes) for up to 180 minutes to capture the dynamic morphological changes associated with each death pathway [7].

FF-OCT Imaging Setup and Parameters

Imaging is performed using a custom-built time-domain FF-OCT system with the following typical specifications [45] [7]:

- Light Source: Broadband halogen lamp (center wavelength: 650 nm, spectral width: 200 nm)

- Interferometer: Linnik-configured Michelson interferometer with identical 40× water-immersion objectives (NA: 0.8)

- Detection: CCD camera (1024 × 1024 pixels, 12-bit, 20 fps)

- Phase Shifting: Piezoelectric actuator attached to reference mirror (20 nm resolution)

- Axial Resolution: <1 μm (achieved through broad spectral bandwidth)

- Lateral Resolution: <1 μm (determined by objective NA)

For dynamic FF-OCT imaging, systems typically acquire 500 interferograms at a rate of 100 Hz at each depth position, with the entire volumetric acquisition process optimized through parallelized acquisition, data transfer, and processing to achieve a total time of approximately 5.12 seconds per D-FFOCT image [47].

Image Processing and Analysis Techniques

The processing of FF-OCT data involves several specialized algorithms to extract meaningful structural and dynamic information [50] [46] [48]:

- Structural FF-OCT: Uses phase-shifting interferometry (typically 4-phase modulation) to reconstruct en face optical sections by arithmetic combination of phase-shifted interferograms, effectively isolating the sample reflection information while suppressing background signals [7].

- Dynamic FF-OCT: Applies Fourier analysis to time-series data at each pixel to compute power spectral density, with subsequent color-coding of frequency characteristics. Additional processing steps may include singular value decomposition and adaptive threshold filtering to eliminate dynamic artifacts [48].

- 3D Reconstruction: Combines multiple en face sections into z-stacks using precise motorized staging, enabling three-dimensional visualization of cellular structures and surface topography mapping through identification of the depth of maximum intensity at each pixel position [7].

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for FF-OCT Cell Death Studies

| Reagent/Component | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| HeLa Cell Line | Model system for apoptosis/necrosis studies | Human cervical cancer cells (KCLB-10002) |

| Doxorubicin | Apoptosis induction agent | 5 μmol/L in culture medium |

| Ethanol | Necrosis induction agent | 99% concentration |

| Water-Immersion Objectives | High-resolution imaging | 40×, NA=0.8, WD=3.3 mm |

| Broadband Light Source | Interferometry illumination | Halogen lamp, 650 nm center wavelength |

| Piezoelectric Actuator | Reference mirror modulation | 20 nm resolution |

Morphological Differentiation of Apoptosis and Necrosis

Characteristic Features of Apoptotic Cells

FF-OCT imaging reveals a distinct sequence of morphological changes during apoptosis, characterized by well-orchestrated structural modifications that maintain membrane integrity until late stages [45] [7]. The process typically begins with cell contraction and echinoid spine formation, where the cell undergoes shrinkage and develops spike-like protrusions from the surface [45] [7]. This is followed by membrane blebbing, characterized by the formation of bulging, blister-like structures on the cell surface as the cytoskeleton reorganizes and the plasma membrane detaches from underlying structures [45] [51] [7]. Concurrently, filopodia reorganization occurs, with fine cytoplasmic projections retracting or extending in a dynamic manner [7]. As apoptosis progresses, the cell fragments into apoptotic bodies—membrane-bound vesicles containing condensed cytoplasm and organelles—which are eventually phagocytosed by neighboring cells without triggering inflammation [52] [7]. Throughout this process, the nuclear envelope remains intact, and the cell maintains its ability to exclude vital dyes until the final stages [52].

Characteristic Features of Necrotic Cells

In contrast to the organized process of apoptosis, necrosis presents as a disorderly series of structural deteriorations resulting from catastrophic cellular damage [45] [7]. The most prominent feature is rapid membrane rupture, where the plasma membrane becomes compromised, leading to uncontrolled release of intracellular contents [45] [7]. This is accompanied by intracellular content leakage, as cytoplasmic components spill into the extracellular space, often triggering inflammatory responses in surrounding tissues [45] [7]. Necrotic cells typically exhibit cell swelling rather than contraction, as ion homeostasis collapses and osmotic balance is disrupted [52] [7]. There is also an abrupt loss of adhesion structures, causing detached cells to float freely in the culture medium [45] [7]. Unlike apoptosis, where organelles remain largely intact until late stages, necrosis involves widespread organelle degradation, including mitochondrial swelling and endoplasmic reticulum dilation, visible as loss of internal structural detail in FF-OCT images [7].

Table 2: Comparative Morphological Features of Apoptosis and Necrosis Visualized by FF-OCT

| Morphological Feature | Apoptosis | Necrosis |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Size | Contraction/SHRINKAGE | Swelling/INCREASE |

| Plasma Membrane | Intact until late stages; Membrane blebbing | Early rupture; Loss of integrity |

| Nuclear Morphology | Chromatin condensation; Nuclear fragmentation | Nonspecific degradation |

| Cytoplasmic Organelles | Initially intact; Sequestered in apoptotic bodies | Swelling; Generalized disruption |

| Cellular Adhesion | Gradual loss maintained until late stages | Abrupt and early loss |

| Inflammatory Response | None (phagocytosis by adjacent cells) | Marked (release of intracellular contents) |

| Filopodia | Reorganization | Disintegration |

| Time Course | Progressive (hours) | Rapid (minutes to hours) |

Experimental Data and Comparative Analysis

Quantitative Assessment of Morphological Changes

FF-OCT enables not only qualitative visualization but also quantitative analysis of morphological parameters during cell death. Using FF-OCT-based three-dimensional topographic mapping, researchers can track changes in cell volume, surface area, and height distribution with submicrometer resolution [7]. Apoptotic cells typically show a progressive decrease in volume (up to 30-50% reduction) accompanied by an initial increase in surface roughness due to membrane blebbing, followed by smoothing as the cell fragments into apoptotic bodies [7]. In contrast, necrotic cells demonstrate rapid volume increase (up to 50-100% expansion) followed by sudden collapse as the membrane ruptures [7]. The integration of interference reflection microscopy (IRM)-like imaging with FF-OCT provides additional quantitative data on cell-substrate adhesion, with apoptotic cells showing gradual detachment while necrotic cells exhibit abrupt loss of adhesion contacts [45] [7].

Temporal Dynamics of Cell Death Processes

The dynamic imaging capabilities of FF-OCT reveal significant differences in the timing and progression of apoptotic versus necrotic pathways. Apoptosis typically follows a slower, more synchronized time course, with initial morphological changes appearing 60-120 minutes after doxorubicin exposure and progressing over several hours [7]. Membrane blebbing generally peaks around 2-3 hours post-induction, followed by fragmentation into apoptotic bodies [7]. In contrast, ethanol-induced necrosis manifests within minutes, with membrane rupture and content leakage occurring within 30-60 minutes of treatment [7]. The real-time monitoring capability of FF-OCT allows researchers to precisely document these temporal patterns and identify transitional stages that might be missed with fixed-timepoint sampling methods.

Comparative Advantages of FF-OCT in Cell Death Research

Performance Relative to Alternative Imaging Modalities

When compared to other imaging techniques commonly used in cell death research, FF-OCT offers several distinct advantages that make it particularly suitable for distinguishing apoptosis from necrosis:

Versus Fluorescence Microscopy: FF-OCT provides label-free imaging that eliminates phototoxicity and photobleaching concerns, enabling longer-term observation of dynamic processes without altering native cell physiology [45] [47]. While fluorescence methods offer molecular specificity through targeted probes, they cannot reliably distinguish apoptosis from necrosis without multiple staining protocols that may themselves affect cell viability [7].

Versus Electron Microscopy: Although electron microscopy provides superior resolution, it requires sample fixation and sectioning, precluding real-time observation of dynamic processes [45] [7]. FF-OCT enables live-cell monitoring of the entire death process without introducing artifacts from chemical fixation or processing.

Versus Quantitative Phase Microscopy (QPM): While both are label-free techniques, FF-OCT provides better optical sectioning capabilities and more direct visualization of intracellular structures [7]. QPM images phase shifts in transmitted light and may struggle with low refractive index contrast, whereas FF-OCT detects back-scattered light with greater sensitivity to fine structural details [7].