DNA Fragmentation Laddering Detection by Gel Electrophoresis: A Complete Guide from Principles to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on detecting DNA fragmentation laddering via gel electrophoresis.

DNA Fragmentation Laddering Detection by Gel Electrophoresis: A Complete Guide from Principles to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on detecting DNA fragmentation laddering via gel electrophoresis. It covers foundational principles, detailing how the characteristic DNA ladder pattern serves as a key biomarker for programmed cell death. The content delivers detailed methodological protocols for agarose and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, alongside advanced troubleshooting guides for common issues like smearing and faint bands. Finally, it explores validation techniques and compares gel electrophoresis with modern alternatives like flow cytometry and capillary electrophoresis, providing a complete framework for applying this essential technique in biomedical research and drug discovery.

Understanding DNA Laddering: From Apoptosis Biomarker to Electrophoresis Fundamentals

DNA Fragmentation Laddering as a Hallmark of Apoptosis

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is a fundamental biological process essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis, ensuring proper development, and eliminating damaged or unnecessary cells in multicellular organisms [1]. A defining biochemical hallmark of apoptosis is the systematic cleavage of nuclear DNA into oligonucleosomal fragments, a phenomenon visually recognizable as DNA laddering on an agarose gel [1] [2]. This characteristic pattern, distinct from the smeared appearance of necrotic cell death, serves as a definitive marker for identifying apoptotic cells and is widely used across various fields of biological research [3] [2].

The process of DNA fragmentation is orchestrated by the activation of a specific endogenous nuclease, the Caspase-Activated DNase (CAD) [1] [3]. During apoptosis, CAD cleaves DNA at the internucleosomal linker regions, generating fragments that are multiples of approximately 180-200 base pairs [1]. This protocol details a robust method for extracting and visualizing this fragmented DNA, providing researchers with a direct and visual confirmation of apoptotic cell death. The technique is particularly valuable in cancer research, toxicology, and drug development for evaluating the efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents and other treatments designed to induce programmed cell death [1].

Core Principles and Significance

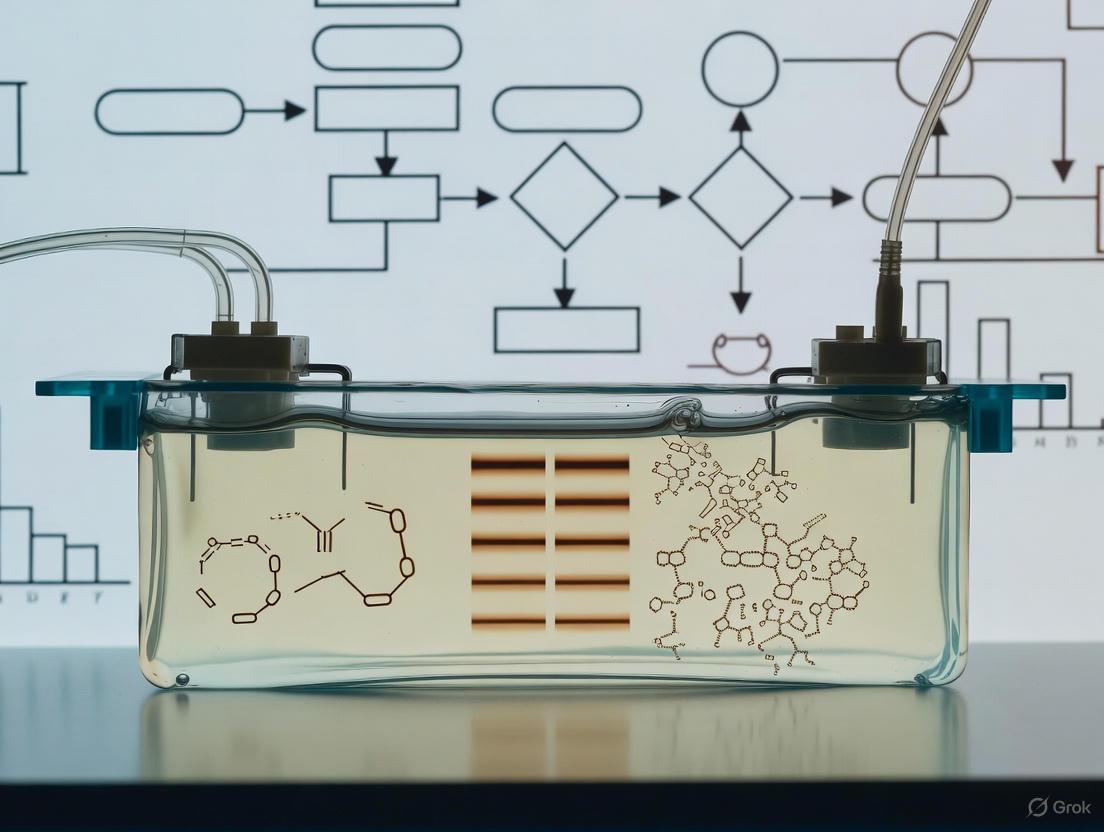

The DNA laddering assay is based on the detection of a specific biochemical event in the apoptotic pathway. The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways that lead to DNA fragmentation and the subsequent experimental workflow for its detection.

This characteristic DNA laddering is a late-stage event in apoptosis, typically occurring after key morphological changes like cell shrinkage and chromatin condensation [1]. The diagram above outlines the two primary apoptotic pathways—the extrinsic (death receptor) and intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathways—which converge to activate the executioner caspases. These caspases, in turn, activate CAD, leading to the systematic cleavage of DNA [1]. The experimental workflow for detecting this fragmentation involves cell lysis, DNA purification, and visualization via gel electrophoresis.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Reagent Preparation

The following reagents are essential for the successful execution of the DNA laddering assay. Precise preparation is critical for reproducibility.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for DNA Fragmentation Analysis

| Reagent | Composition / Type | Function |

|---|---|---|

| TES Lysis Buffer [3] | 10 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5% SDS | Disrupts cell and nuclear membranes to release fragmented chromatin. |

| Proteinase K [1] [3] | 20 mg/mL solution | Digests nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins, facilitating DNA purification. |

| RNase Cocktail [1] [3] | DNase-free RNase A | Removes RNA to prevent interference during gel electrophoresis. |

| Phenol/Chloroform/Isoamyl Alcohol [1] [4] | 25:24:1 ratio | Purifies DNA by separating it from proteins and cellular debris. |

| Ethanol & Sodium Acetate [1] [4] | 100% Ethanol, 3M Sodium Acetate (pH 5.2) | Precipitates and concentrates nucleic acids from the aqueous solution. |

| TAE Buffer [3] [5] | 40 mM Tris, 20 mM Acetic Acid, 1 mM EDTA | Running buffer for gel electrophoresis; ideal for longer DNA fragments. |

| Agarose Gel [1] [3] | 1-2% agarose in TAE | Matrix for separating DNA fragments by size via electrophoresis. |

| Ethidium Bromide / SYBR Gold [1] [5] | 0.5-1.0 µg/mL | Fluorescent dye that intercalates with DNA for UV visualization. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

This protocol is adapted from established methods [1] [3] [4] and is suitable for both suspension and adherent cell cultures.

Stage 1: Cell Harvesting and Lysis

- Harvest Cells: Pellet 5 × 10^5 to 5 × 10^6 cells by centrifugation at 2000 rpm (approximately 500-700 × g) for 10 minutes at 4°C [3]. Using fewer cells may result in undetectable DNA, while too many cells can make the DNA difficult to handle.

- Lyse Cells: Resuspend the cell pellet thoroughly in 0.5 mL of TES Lysis Buffer (or a similar detergent-based buffer containing Triton X-100 or NP-40) by vigorous vortexing [1] [3].

- Incubate: Place the lysate on ice for 30 minutes to ensure complete disruption of cellular structures [1].

- Centrifuge: Centrifuge the lysate at a high speed (27,000 × g for 30 minutes) to separate the fragmented, low-molecular-weight DNA (in the supernatant) from intact chromatin and cellular debris (in the pellet) [1].

Stage 2: DNA Precipitation and Purification

- Precipitate DNA: Transfer the supernatant to a new tube. Add 0.1 volume of 2M NaCl and 2.5 volumes of ice-cold 100% ethanol (or 600 µL ethanol and 150 µL 3M sodium acetate, pH 5.2 [1]). Mix by pipetting and incubate at -80°C for 1 hour [1] [4].

- Pellet DNA: Centrifuge at 12,000-20,000 × g for 10-20 minutes to pellet the DNA. Carefully discard the supernatant without disturbing the often loose pellet [1] [4].

- Digest Contaminants: Resuspend the DNA pellet in 100-400 µL of Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer. Add:

- Purify DNA: Extract the DNA using an equal volume of phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1). Centrifuge and transfer the upper aqueous phase to a new tube. Precipitate the DNA again with ethanol/sodium acetate, wash the pellet with 80% ethanol, air-dry, and resuspend in 20-100 µL of TE buffer [1] [4].

Stage 3: Agarose Gel Electrophoresis and Visualization

- Prepare Gel: Cast a 1.5-2% agarose gel in TAE buffer. Incorporate 0.5 µg/mL ethidium bromide directly into the gel, or plan to stain the gel after electrophoresis [1] [3] [4].

- Load and Run Samples: Mix the DNA samples with a 6X loading dye (containing bromophenol blue or other tracking dyes). Load 10-20 µL of each sample into the wells. Include a DNA molecular weight marker (ladder). Run the gel at a low voltage (35-50 V) for 1.5-4 hours to achieve optimal separation of small DNA fragments [3] [5].

- Visualize: If not pre-stained, immerse the gel in a 1 µg/mL ethidium bromide solution for 10-60 minutes. Destain in water if necessary. Visualize the DNA bands under ultraviolet (UV) light and document with a gel imaging system [1] [3].

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Expected Results and Quantification

The successful execution of the protocol yields distinct patterns on the agarose gel that allow for the differentiation of apoptotic, necrotic, and viable cells.

Table 2: Interpretation of DNA Fragmentation Patterns

| Cell State | Gel Pattern | Description | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apoptotic | DNA Laddering | A series of discrete bands at ~180-200 bp and its multiples (e.g., 360 bp, 540 bp, etc.) [1] [3] [2]. | Indicates activation of CAD and internucleosomal cleavage, confirming programmed cell death. |

| Necrotic | DNA Smear | A continuous, diffuse smear of DNA across a wide size range [3] [2]. | Results from random, unregulated DNA degradation characteristic of traumatic cell death. |

| Viable / Healthy | Single High-Molecular-Weight Band | A single, sharp band at the top of the gel, near the well [3]. | Represents intact, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA that has not been fragmented. |

While this assay is highly specific for apoptosis, it is considered semi-quantitative. For precise quantification of cell death, researchers should employ complementary techniques such as flow cytometry-based TUNEL assays or analysis of caspase activation [1] [2].

Technical Optimization and Troubleshooting

Optimal gel resolution is critical for clear data interpretation. Key parameters for optimization include:

- Agarose Concentration: A 1.5-2% agarose gel provides the best resolution for DNA fragments in the 100-2000 bp range, which is ideal for visualizing the apoptotic ladder [5].

- Running Buffer: TAE buffer is generally preferred for resolving longer DNA fragments and is compatible with downstream enzymatic reactions [5].

- Voltage: Running the gel at a low voltage (35-50 V) improves the resolution of small DNA fragments by minimizing band smearing and the "smiling effect" caused by uneven heating [3] [5].

- DNA Quantity: Ensure at least 20 ng of DNA per band is loaded for detection with ethidium bromide. Overloading wells can cause poor separation and distorted band shapes [5].

Table 3: Common Issues and Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or absent DNA ladder | Insufficient apoptotic cells; poor DNA recovery; loose pellet loss. | Use recommended cell numbers (5x10^5); handle pellet with extreme care after precipitation; include a positive control. |

| DNA smear instead of ladder | Sample degradation; incomplete protein digestion; gel ran at too high voltage. | Use fresh Proteinase K and RNase; ensure complete digestion; run gel at lower voltage. |

| High background or smearing | Contamination with RNA or protein. | Ensure complete RNase and Proteinase K treatment; perform phenol/chloroform extraction steps carefully. |

| No DNA detected in any lane | Failed cell lysis or DNA precipitation. | Verify lysis buffer composition; ensure ethanol is 100% and precipitation is done at -80°C. |

Comparison with Other Apoptosis Detection Methods

The DNA laddering assay is one of several methods available for detecting apoptosis. The table below compares its key attributes with other commonly used techniques.

Table 4: Comparison of Key Apoptosis Detection Methods

| Method | Target / Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Suitable for Stage Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Laddering | Internucleosomal DNA fragmentation [1] [2]. | Direct, visual confirmation; cost-effective; specific for apoptosis. | Semi-quantitative; requires many cells; late-stage event [1]. | Late |

| TUNEL Assay | Labeling of 3' DNA ends [1] [2]. | High sensitivity; can be used on tissue sections; quantitative via flow cytometry. | Can yield false positives; more expensive; requires specialized equipment [1]. | Mid-Late |

| Annexin V Staining | Phosphatidylserine externalization [1]. | Detects early apoptosis; can distinguish early vs. late apoptosis vs. necrosis. | Requires live cells; sensitive to handling; cannot be used on fixed tissues [1]. | Early |

| Caspase Activity Assay | Protease activity of activated caspases [1] [2]. | Highly specific; quantitative; detects a central event in apoptosis. | May not detect caspase-independent apoptosis; requires specific substrates/assays. | Mid |

Applications in Research and Drug Development

The DNA laddering assay is a versatile tool with broad applications in biomedical research and pharmaceutical development.

- Cancer Research and Therapy: The protocol is extensively used to evaluate the efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents by determining their ability to induce apoptosis in tumor cell lines [1]. It helps in studying the role of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins in cancer progression and treatment resistance.

- Toxicology and Safety Assessment: In toxicology, the assay helps determine the cytotoxic potential of chemical compounds or environmental stressors, distinguishing between apoptotic and necrotic cell death mechanisms [1].

- Neurobiology and Disease Modeling: DNA laddering has been applied in models of neurological diseases, such as detecting apoptosis in brain lesions and in Parkinson's disease models using SHSY-5Y cells exposed to neurotoxic insults [2] [4].

- Immunology and Developmental Biology: The method is crucial for studying immune-mediated cytotoxicity and the role of apoptosis in normal tissue remodeling and development [1] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit

To successfully implement the DNA laddering assay, a standard molecular biology laboratory should be equipped with the following core resources.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Equipment

| Category | Item | Specific Recommendation / Function |

|---|---|---|

| Core Reagents | Lysis Buffer | TES buffer or 10 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA, 0.2% Triton X-100 [1] [3]. |

| Enzymes | DNase-free RNase A and Proteinase K for digesting contaminants [1] [3]. | |

| Precipitation Reagents | 3M Sodium Acetate (pH 5.2) and 100% Ethanol for DNA concentration [1]. | |

| Gel Staining | Ethidium bromide (0.5-1.0 µg/mL) or more sensitive SYBR Gold [1] [5]. | |

| Essential Equipment | Centrifuge | Refrigerated centrifuge capable of speeds up to 27,000 × g [1] [3]. |

| Gel Electrophoresis System | Tank, power supply, and gel casting tray [3] [5]. | |

| Visualization System | UV transilluminator with gel documentation capabilities [1] [3]. | |

| Consumables | DNA Molecular Weight Marker | Ladder with bands in the 100-2000 bp range for accurate sizing (e.g., 100 bp ladder) [5]. |

| Loading Dye | 6X concentrate with tracking dyes (e.g., bromophenol blue) [3] [5]. |

Core Principles of Nucleic Acid Separation by Gel Electrophoresis

Gel electrophoresis is a foundational technique in molecular biology for separating nucleic acid fragments based on size. This method is particularly crucial in apoptosis research, where it is used to detect the characteristic DNA "laddering" pattern—a key hallmark of programmed cell death resulting from the internucleosomal cleavage of genomic DNA. This application note details the core principles, protocols, and reagent solutions essential for researchers and drug development professionals employing this technique in the context of DNA fragmentation analysis.

Core Principles and Gel Matrix Selection

Nucleic acid gel electrophoresis separates DNA and RNA fragments by forcing them to migrate through a gel matrix under an electrical field. The negatively charged phosphate backbone of DNA causes it to move toward the positive anode, with smaller fragments moving faster through the pores of the gel than larger ones [6] [7].

The choice of gel matrix is the primary determinant for successful separation, with agarose and polyacrylamide being the two most common types [8].

- Agarose Gels: Derived from red algae, agarose is a polysaccharide polymer that forms a gel matrix with pores sizes suitable for separating nucleic acid fragments ranging from 0.1 to 25 kilobases (kb). It is ideal for routine separation of larger DNA fragments, such as in DNA laddering assays [8].

- Polyacrylamide Gels: A synthetic polymer of acrylamide monomers, polyacrylamide forms gels with much smaller pore sizes than agarose. It is used for high-resolution separation of smaller nucleic acid fragments (typically less than 1 kb), capable of resolving fragments that differ by a single nucleotide [8].

The table below summarizes the key differences and optimal separation ranges for these two gel matrices.

Table 1: Comparison of Agarose and Polyacrylamide Gel Matrices

| Feature | Agarose Gel | Polyacrylamide Gel |

|---|---|---|

| Source | Polysaccharide from red algae [8] | Synthetic polymer [8] |

| Gel Formation | Physical: dissolves in water and solidifies upon cooling [8] | Chemical: polymerizes with a crosslinking agent (bis-acrylamide) [8] |

| DNA Separation Range | 50 bp – 50,000 bp [8] | 5 bp – 3,000 bp [8] |

| Resolving Power | 5-10 nucleotides [8] | Single nucleotide [8] |

| Primary Application | General purpose separation, apoptosis DNA laddering | High-resolution analysis of small fragments |

Optimizing Separation by Gel Concentration

The resolution of nucleic acid fragments is controlled by adjusting the concentration of the gel, which determines the pore size. Higher percentage gels have smaller pores and provide better separation for smaller fragments, while lower percentage gels with larger pores are used for resolving larger fragments [8].

Table 2: Recommended Agarose Gel Percentages for DNA Separation

| Agarose Gel Percentage (%) | Effective Range of Separation (base pairs) [8] |

|---|---|

| 0.5 | 2,000 – 50,000 |

| 0.7 | 800 – 12,000 |

| 1.0 | 400 – 8,000 |

| 1.5 | 200 – 3,000 |

| 2.0 | 100 – 2,000 |

| 3.0 | 25 – 1,000 |

| 4.0 | 10 – 500 |

Table 3: Recommended Polyacrylamide Gel Percentages for DNA Separation

| Polyacrylamide Gel Percentage (%) | Effective Range of Separation (base pairs, non-denaturing conditions) [8] |

|---|---|

| 3.5 | 100 – 1,000 |

| 5.0 | 80 – 500 |

| 8.0 | 60 – 400 |

| 12.0 | 50 – 200 |

| 20.0 | 5 – 100 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standard Protocol for Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

This protocol is adapted for a standard 1% agarose gel, which is suitable for a wide range of DNA fragment sizes [9] [6].

I. Gel Preparation and Casting

- Prepare Buffer: Use 1x TAE or TBE as the electrophoresis buffer [6].

- Mix Agarose: Combine 0.5 g of agarose powder with 50 mL of 1x buffer in a microwavable flask to create a 1% gel solution [9] [6].

- Dissolve Agarose: Heat the mixture in a microwave using short bursts (20-30 seconds), swirling in between, until the agarose is completely dissolved and the solution is clear [9].

- Cool Solution: Allow the dissolved agarose to cool to approximately 50-55°C to prevent warping of the gel casting tray [9].

- Add Stain: Incorporate a fluorescent nucleic acid stain, such as 2-3 µL of ethidium bromide (10 mg/mL stock) or a safer alternative like DNA Safe Stain, into the cooled agarose and mix thoroughly by swirling [9] [6].

- Cast Gel: Pour the agarose into a casting tray with a well comb in place. Remove any bubbles with a pipette tip. Allow the gel to solidify completely at room temperature for 20-30 minutes [9].

II. Sample and Gel Box Setup

- Prepare Samples: Mix DNA samples with a loading dye containing a dense agent like glycerol and visible tracking dyes (e.g., bromophenol blue). Typically, use 5 µL of loading dye per 25 µL of sample [6].

- Set Up Electrophoresis Unit: Once solidified, remove the comb and buffer dams from the gel. Place the gel in the electrophoresis chamber and submerge it completely in 1x buffer [9].

- Load Samples: Pipette your DNA samples and an appropriate DNA ladder (e.g., 100 bp ladder) into the wells. Record the sample-to-well correspondence [9].

III. Electrophoretic Run and Visualization

- Run Gel: Connect the lid to the power supply, ensuring the black (negative) and red (positive) electrodes are correctly aligned. Run the gel at 50-150 V until the dye front has migrated 75-80% of the way down the gel [9] [6].

- Visualize: After the run, turn off the power, discard the buffer, and carefully transfer the gel to a UV transilluminator for imaging [6].

Specialized Protocol for Apoptosis DNA Laddering Detection

This protocol is designed specifically for the isolation and visualization of the DNA ladder pattern characteristic of apoptosis [1].

Stage 1: Harvesting and Lysing Cells

- Pellet approximately 1x10⁶ cells by centrifugation [1] [10].

- Lyse the cell pellet in 0.5 mL of detergent buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris pH 7.4, 5 mM EDTA, 0.2% Triton X-100) [1].

- Vortex the mixture and incubate on ice for 30 minutes [1].

- Centrifuge at high speed (27,000 x g) for 30 minutes to separate intact chromatin (pellet) from fragmented DNA (supernatant) [1].

- Divide the supernatant into aliquots and add ice-cold 5 M NaCl [1].

Stage 2: Precipitating and Purifying DNA

- Add 600 µL of ethanol and 150 µL of 3 M sodium-acetate (pH 5.2) to the supernatant to precipitate the DNA. Mix thoroughly [1].

- Incubate at -80°C for 1 hour to enhance precipitation [1].

- Centrifuge at 20,000 x g for 20 minutes to pellet the DNA. Carefully discard the supernatant [1].

- Re-dissolve the DNA pellet in Tris-EDTA buffer [1].

- Treat the DNA extract with DNase-free RNase (e.g., 2 µL of 10 mg/mL) for several hours at 37°C to remove RNA [1].

- Add Proteinase K and incubate overnight at 65°C to digest proteins [1].

- Perform a final phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation to purify the DNA [1].

Stage 3: Electrophoretic Analysis

- Air-dry the final DNA pellet and resuspend it in 20 µL of Tris-acetate EDTA buffer with loading dye [1].

- Separate the DNA electrophoretically on a 2% agarose gel containing a fluorescent stain [1] [10]. Run at 100 V for 40-50 minutes [10].

- Visualize the DNA fragments using a UV transilluminator. A positive apoptotic signal will appear as a ladder of bands in increments of approximately 180-200 base pairs [1].

DNA Laddering Assay Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful nucleic acid electrophoresis and DNA fragmentation analysis rely on a set of key reagents and materials.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Gel Electrophoresis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Agarose | Forms the porous gel matrix that separates DNA by size [8]. | Choose percentage based on desired fragment resolution (see Table 2). |

| Electrophoresis Buffer (TAE/TBE) | Conducts current and maintains stable pH during the run [6]. | Use the same batch for gel preparation and as running buffer. |

| DNA Stain (e.g., Ethidium Bromide) | Intercalates with DNA, allowing visualization under UV light [6]. | Handle with care; known mutagen. Safer alternatives are available [11]. |

| Loading Dye | Adds density for well loading and contains visible dyes to track migration [9] [6]. | Typically contains glycerol and dyes like bromophenol blue. |

| DNA Ladder | A mix of DNA fragments of known sizes for estimating sample fragment sizes [9]. | Choose a ladder with a range that covers your fragments of interest. |

| Lysis Buffer (for Apoptosis) | Breaks open cells and releases fragmented genomic DNA [1]. | Contains detergent (Triton X-100) and EDTA. |

| RNase & Proteinase K (for Apoptosis) | Enzymes that digest RNA and proteins, respectively, for DNA purification [1]. | Must be DNase-free to prevent sample degradation. |

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Identifying Apoptotic DNA Laddering

In a successful apoptosis assay, genomic DNA from healthy cells remains largely intact and will appear as a high-molecular-weight band near the top of the gel lane, close to the well. In contrast, DNA from apoptotic cells exhibits a characteristic "ladder" due to internucleosomal cleavage, appearing as a series of distinct bands starting around 180-200 base pairs and increasing in multiples of this size [1]. Necrotic cell death, by comparison, typically results in a continuous "smear" of DNA fragments across the lane due to random digestion [1].

Interpreting Plasmid DNA Forms

When analyzing plasmids, different structural conformations migrate at different speeds [7]:

- Supercoiled (CCC): Most compact form; migrates fastest and furthest [7].

- Linear: Results from a double-strand break; migrates between supercoiled and open circular forms [7].

- Open Circular (OC): Results from a single-strand break (nick); least compact and migrates slowest [7].

Guide to Interpreting Gel Results

Agarose Gel Properties and Molecular Sieving Mechanisms

Agarose gel electrophoresis remains a cornerstone technique in molecular biology and biochemistry laboratories worldwide, serving as a fundamental method for the separation and analysis of nucleic acids. Its principle involves the migration of charged molecules through a porous matrix under the influence of an electric field, separating them based on size and charge. The agarose gel matrix, derived from red algae, forms a three-dimensional network that acts as a molecular sieve, differentially retarding the movement of molecules as they travel through the gel. This molecular sieving mechanism is particularly crucial for DNA fragmentation laddering detection, a key method for identifying programmed cell death (apoptosis) in cellular research, cancer biology, and drug development studies. When cells undergo apoptosis, endonucleases cleave DNA at internucleosomal sites, generating fragments in approximately 200 base pair increments. The separation and visualization of these fragments via agarose gel electrophoresis produces a characteristic "ladder" pattern, distinguishing apoptotic cells from those undergoing necrotic death. Understanding the precise properties of agarose gels and their molecular sieving behavior is therefore essential for optimizing this and other critical diagnostic techniques in biomedical research.

Fundamental Properties of Agarose Gels

Chemical Structure and Gel Formation

Agarose is a linear polysaccharide extracted from red algae, composed of repeating units of agarobiose [12]. Each agarobiose unit consists of D-galactose and 3,6-anhydro-α-L-galactose, with numerous hydroxyl groups that readily form hydrogen bonds [12]. The gelation process is thermoreversible and concentration-dependent. When heated to 90-100°C, hydrogen bonds break, dispersing agarose into water as random coils to form a clear solution. As the temperature cools to 30-40°C, the molecular chains intertwine through hydrogen bonding, forming a double helix structure that aggregates into a three-dimensional network [12] [13]. This network creates pores through which molecules must travel during electrophoresis. The resulting gel structure is heterogeneous, consisting of agarose-rich and agarose-poor phases formed through simultaneous gelation and phase separation during cooling [14].

Molecular Sieving Mechanism

The separation of DNA fragments in agarose gels occurs through a molecular sieving process where the gel matrix acts as a porous sieve. The agarose network creates interconnected channels with defined pore sizes that differentially retard the movement of DNA molecules based on their size. Smaller DNA fragments navigate these pores more easily and migrate faster toward the anode, while larger fragments encounter greater resistance and migrate more slowly [15] [16]. This size-dependent separation forms the basis for resolving DNA fragmentation patterns in apoptosis detection. The efficiency of separation depends on the relationship between DNA fragment size and gel pore size, which can be optimized by adjusting agarose concentration [15] [16] [5].

Table 1: Relationship Between Agarose Concentration and DNA Separation Range

| Agarose Concentration (%) | Optimal DNA Separation Range (base pairs) | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|

| 0.7% | 5,000 - 10,000+ | Large DNA fragments, Southern blotting |

| 1.0% | 500 - 10,000 | Standard PCR products, genotyping |

| 1.5% | 300 - 5,000 | General purpose DNA separation |

| 2.0% | 100 - 3,000 | Small DNA fragments, apoptosis ladders |

| 3.0% | 50 - 1,000 | Very small fragments, oligonucleotides |

Experimental Protocols for DNA Fragmentation Detection

DNA Fragmentation Laddering Assay

The DNA fragmentation laddering assay provides a reliable method for detecting internucleosomal DNA cleavage, a hallmark of apoptosis. This protocol enables researchers to distinguish apoptotic cell death from necrosis through the characteristic DNA ladder pattern observed after agarose gel electrophoresis [10] [1].

Cell Harvesting and Lysis

- Pellet cells by centrifugation at 1,200 rpm for 5 minutes [1].

- Lyse cells in 0.5 mL detergent buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.4, 5 mM EDTA, 0.2% Triton X-100 or NP-40) [1].

- Vortex the mixture thoroughly and incubate on ice for 30 minutes [1].

- Centrifuge at 27,000 × g for 30 minutes to separate fragmented DNA from intact chromatin [1].

- Divide supernatants containing fragmented DNA into two 250 µL aliquots [1].

- Add 50 µL ice-cold 5 M NaCl to each aliquot and vortex to mix [1].

DNA Precipitation and Purification

- Add 600 µL ethanol and 150 µL 3 M sodium-acetate (pH 5.2) to each aliquot and mix by pipetting [1].

- Incubate tubes at -80°C for 1 hour to precipitate DNA [1].

- Centrifuge at 20,000 × g for 20 minutes and carefully discard supernatants without disturbing the pellets [1].

- Pool DNA extracts by re-dissolving pellets in a total of 400 µL extraction buffer (10 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA) [1].

- Add DNase-free RNase (2 µL of 10 mg/mL) and incubate for 5 hours at 37°C to remove RNA [1].

- Add 25 µL proteinase K (20 mg/mL) and 40 µL of buffer (100 mM Tris pH 8.0, 100 mM EDTA, 250 mM NaCl), then incubate overnight at 65°C to digest proteins [1].

- Extract DNA with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and precipitate with ethanol [1].

- Carefully discard supernatant and air-dry the pellet [1].

Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

- Resuspend DNA in 20 µL Tris-acetate EDTA buffer supplemented with 2 µL sample buffer (0.25% bromophenol blue, 30% glycerol) [1].

- Prepare a 2% agarose gel by dissolving agarose in TAE or TBE buffer containing 1 µg/mL ethidium bromide [10] [1]. For optimal resolution of apoptosis fragments (multiples of ~180-200 bp), 1.8-2% agarose gels are recommended [10].

- Load DNA samples and separate electrophoretically at 100 V for 40-60 minutes [10].

- Visualize DNA fragments by ultraviolet transillumination [10] [1]. Apoptotic cells display a characteristic ladder pattern, while necrotic cells show a smeared pattern.

Diagram 1: DNA Fragmentation Laddering Assay Workflow

Alternative Rapid DNA Fragmentation Protocol

For situations requiring faster analysis, a modified protocol can be employed:

- Seed cells at 1 × 10^6 cells/well in a 24-well plate and incubate for 24 hours [10].

- Treat cells with apoptosis-inducing agents for 24 hours [10].

- Collect cells and extract DNA using a commercial kit (e.g., FlexiGene DNA kit) [10].

- Analyze aliquots (2 μg DNA) using electrophoresis at 100 V for 40 minutes in 1.8% agarose gels containing 0.1% ethidium bromide [10].

- Visualize DNA fragments using a UV transilluminator and capture gel images [10].

Optimization Strategies for DNA Separation

Agarose Concentration and Buffer Selection

The pore size of agarose gels, which directly governs their sieving properties, is primarily determined by agarose concentration. Lower concentrations (0.7-1%) generate larger pores suitable for resolving bigger DNA fragments (>5,000 bp), while higher concentrations (1.8-2%) create smaller pores that provide better resolution for smaller fragments (100-3,000 bp) typical of apoptosis ladders [15] [5]. The choice of electrophoresis buffer also significantly impacts separation efficiency. TAE (Tris-acetate-EDTA) buffer offers better resolution for longer DNA fragments (>1 kb) and is compatible with downstream enzymatic reactions, while TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA) buffer provides superior separation of smaller fragments (<1 kb) due to its higher buffering capacity but is not recommended for applications involving enzymatic steps [5].

Table 2: Electrophoresis Buffer Properties and Applications

| Buffer System | Composition | Optimal Fragment Size | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAE (Tris-Acetate-EDTA) | 40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0 | >1,000 bp | Better resolution for large fragments; compatible with enzymatic reactions | Lower buffering capacity; not suitable for long runs |

| TBE (Tris-Borate-EDTA) | 45 mM Tris-borate, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0 | <1,000 bp | Higher buffering capacity; better resolution for small fragments; suitable for long runs | Can interfere with enzymatic reactions; slower migration (10% slower than TAE) |

Practical Electrophoresis Conditions

Several practical factors must be optimized to ensure high-quality DNA separation:

DNA Quantity: Load at least 20 ng per band for ethidium bromide or SYBR Safe staining, or 1 ng per band for more sensitive SYBR Gold staining [5]. Overloading can cause band distortion and altered migration, while underloading produces faint bands [5].

Voltage Conditions: Apply 5-10 V/cm of gel length [16]. High voltage causes uneven heating and "smiling" effects where DNA in center lanes migrates faster than in peripheral lanes [5].

Buffer Volume: Submerge gels with 3-5 mm of buffer covering the surface. Insufficient buffer causes poor resolution, band distortion, or gel melting, while excess buffer decreases DNA mobility [5].

Sample Loading Dyes: Use appropriate dyes that don't mask bands of interest. Common dyes include Orange G (migrates at ~50 bp), bromophenol blue (~400 bp), and xylene cyanol (~4,000 bp) [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DNA Fragmentation Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Agarose (Type I-IV) | Forms separation matrix with molecular sieving properties | Choose concentration based on target DNA size: 2% for apoptosis ladders, 0.7-1% for larger fragments [15] [5] |

| TAE or TBE Buffer | Provides conducting medium with appropriate pH and ionic strength | TAE for larger fragments, TBE for smaller fragments; prepare fresh or from concentrated stock [5] |

| Ethidium Bromide | Fluorescent DNA intercalating dye for visualization | Use at 0.1-1 µg/mL in gel and/or buffer; mutagenic—handle with gloves [10] [1] |

| SYBR Safe DNA Stain | Alternative less-toxic fluorescent nucleic acid stain | More sensitive than ethidium bromide; compatible with blue light transillumination [5] |

| DNA Ladder/Marker | Molecular weight standard for size determination | Choose ladders with appropriate range (e.g., 100-3,000 bp for apoptosis); chromatography-purified for sharp bands [5] |

| Loading Dye/Buffer | Increases density for well loading; contains tracking dyes | Contains glycerol/sucrose/Ficoll; dye selection critical to avoid masking bands of interest [5] |

| Cell Lysis Buffer | Releases and solubilizes fragmented DNA from cells | Typically contains Tris buffer, EDTA, and detergent (Triton X-100 or NP-40) [1] |

| Proteinase K & RNase | Digest proteins and RNA for DNA purification | Essential for clean DNA preparation; must be DNase-free [1] |

| Phenol/Chloroform/IAA | Organic extraction for protein removal | 25:24:1 ratio; separates DNA into aqueous phase [1] |

| Ethanol & Sodium Acetate | Precipitation of nucleic acids from aqueous solution | Ice-cold ethanol with salt; -80°C incubation improves yield [1] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Even well-optimized protocols can encounter challenges. The following guidance addresses common issues in DNA fragmentation detection:

Weak or Absent DNA Ladder: This may result from insufficient cell lysis, poor DNA recovery, or degraded samples. Ensure proper buffer preparation and adherence to incubation times. Include positive controls to validate the assay [1].

Smearing on Gel: Overloading or incomplete protein digestion causes smearing. Use fresh proteinase K and RNase, and ensure appropriate DNA quantity [1].

"Smiling" Effect: When DNA in center lanes migrates faster than in peripheral lanes, forming a crescent shape. This results from uneven heating, typically caused by high voltage. Run gel at lower voltage and check for loose contacts in the electrophoresis tank [5].

Diffuse Bands: Can be caused by bubbles in the gel, ripping of wells during comb removal, or incorrect buffer concentration. Pour gels carefully to avoid bubbles, ensure sufficient gel thickness under combs, and maintain proper buffer conditions [16] [5].

Diagram 2: Agarose Gel Electrophoresis Troubleshooting Guide

Agarose gel electrophoresis provides an accessible yet powerful tool for detecting DNA fragmentation patterns characteristic of apoptosis. The molecular sieving mechanism of agarose gels, governed by their concentration-dependent pore structure, enables clear resolution of the oligonucleosomal ladder that distinguishes programmed cell death from other forms of cellular demise. Through careful attention to protocol details—including appropriate agarose concentration, buffer selection, DNA quantity, and electrophoresis conditions—researchers can obtain reliable, reproducible results for this critical assay. While the DNA fragmentation laddering approach has limitations in quantification and sensitivity compared to more advanced techniques like TUNEL assays or flow cytometry, its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and visual clarity make it an invaluable method for initial apoptosis screening in basic research, toxicology studies, and drug development applications. Proper implementation of the protocols and optimization strategies outlined in these application notes will ensure researchers can effectively leverage the molecular sieving properties of agarose gels for accurate DNA fragmentation analysis.

Within the context of DNA fragmentation laddering detection for apoptosis research, the selection of an appropriate DNA staining method is a critical decision that influences not only the sensitivity and clarity of experimental results but also laboratory safety and the viability of downstream applications. Agarose gel electrophoresis serves as a foundational technique for analyzing the characteristic DNA ladder pattern indicative of internucleosomal cleavage during programmed cell death [1]. For decades, ethidium bromide (EtBr) has been the traditional stain used for this purpose. However, its documented mutagenicity and the damaging effects of ultraviolet (UV) light on DNA have driven the development of safer, high-performance alternatives [17] [18]. This application note provides a comparative analysis of ethidium bromide and modern nucleic acid stains, focusing on their utility in DNA fragmentation detection. It offers detailed protocols designed to integrate these stains seamlessly into apoptosis research workflows, ensuring that researchers can make informed choices that optimize both data quality and laboratory safety.

The Science of DNA Staining and Apoptosis Detection

Biochemical Basis of DNA Fragmentation in Apoptosis

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is characterized by a series of precise biochemical events, with DNA fragmentation being a definitive hallmark. This process is orchestrated by the activation of caspases, which in turn activate specific endonucleases, such as CAD (Caspase-Activated DNase). These enzymes cleave nuclear DNA at the internucleosomal linker regions, generating fragments of approximately 180-200 base pairs in length [1]. When separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, these fragments produce a distinctive "ladder" pattern. This pattern is a key diagnostic feature that differentiates apoptotic cell death from necrosis, where DNA cleavage is random and produces a continuous "smear" on a gel [1]. The ability to clearly visualize this ladder is therefore paramount in fields such as cancer research, toxicology, and drug development, where confirming and quantifying apoptosis is essential [1].

Mechanisms of DNA Stain Binding

DNA stains function by binding to nucleic acids and fluorescing upon excitation by light, thereby rendering the DNA visible. The mechanism of binding, however, varies and has implications for both safety and DNA integrity:

- Intercalation: Ethidium bromide is a classic intercalating agent. Its flat, planar structure allows it to insert itself between the stacked base pairs of the DNA double helix. This intercalation event causes the DNA to unwind and lengthen [19] [18]. While this mechanism provides strong fluorescence, it also structurally distorts the DNA, which can interfere with subsequent enzymatic reactions like ligation and transformation.

- Groove Binding: Many modern alternatives, such as SYBR Safe and Diamond Nucleic Acid Dye, are described as groove-binding agents [20]. These dyes typically bind in the minor groove of the DNA helix without disrupting the base-pair stacking. This non-intercalating mode of binding is a key factor in reducing DNA damage and mutation risk, making these stains safer for users and more suitable for applications where DNA integrity is critical, such as molecular cloning [17] [20].

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Stain Binding Mechanisms and Key Characteristics

| Stain | Primary Binding Mechanism | Mutation Risk | Impact on DNA Integrity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethidium Bromide | Intercalation between base pairs | High mutagen [19] [18] | High; UV visualization causes damage [17] |

| SYBR Safe | Groove-binding (non-intercalating) | Lower mutagenicity [17] | Low; compatible with blue light [17] [21] |

| Gel Red | Reported as non-intercalating by manufacturer | Lower mutagenicity [19] [18] | Moderate; uses UV light but claims minimal impact |

| Methylene Blue | Ionic binding to backbone | Non-mutagenic [19] | Low, but sensitivity is very low [19] |

The following diagram illustrates the apoptotic pathway leading to DNA fragmentation and the different binding mechanisms of common DNA stains.

Comprehensive Comparison of DNA Stains

The ideal DNA stain provides high sensitivity, low toxicity, and minimal impact on DNA function. The following tables provide a detailed quantitative and qualitative comparison of commonly used stains to guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate reagent for their apoptosis detection experiments.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance and Safety Data of Common DNA Stains

| Stain | Sensitivity (Detection Limit) | Excitation Maxima | Emission | Acute Oral Toxicity (LD₅₀) | Mutagenicity (Ames Test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethidium Bromide | 1 - 5 ng/band [19] | 300 nm & 360 nm (UV) [19] | ~590 nm (Orange) [19] | Data Not Fully Specified | Mutagen [17] [19] |

| SYBR Safe | 1 - 5 ng/band [19] [20] | 502 nm (Blue) / UV [17] [21] | ~530 nm (Green) [17] | >5,000 mg/kg [17] | Weakly positive with S9 activation; negative in mammalian cells [17] |

| Gel Red | ~0.25 ng/band [19] [18] | 300 nm (UV) [19] [18] | ~595 nm (Red) [19] | Data Not Fully Specified | Less mutagenic than EtBr [19] [18] |

| SYBR Gold | Similar to SYBR Safe [20] | UV / ~495 nm (Blue) [20] | ~537 nm (Green) [20] | Data Not Fully Specified | Data Not Fully Specified |

| Diamond Dye | Similar to SYBR Gold [20] | UV / Blue (instrument dependent) [20] | Green [20] | Data Not Fully Specified | Data Not Fully Specified |

| Methylene Blue | 40 - 100 ng/band [19] | Visible Light ~650 nm [19] | Visible Light [19] | Somewhat toxic if ingested [19] | Non-mutagenic [19] |

Table 3: Practical Application and Disposal Considerations

| Stain | Compatible Visualization Methods | Suitable for Downstream Cloning? | Environmental Impact & Disposal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethidium Bromide | UV transilluminator only [19] | Poor; significant reduction in efficiency [17] | Classified as hazardous waste; requires special disposal [17] [18] |

| SYBR Safe | Blue-light transilluminator or UV [17] [21] | Excellent; minimal impact on cloning efficiency [17] | Not classified as hazardous waste under U.S. RCRA [17] |

| Gel Red | UV transilluminator (standard EtBr filters) [19] [18] | Good; less damaging than EtBr [19] | Reported as less hazardous than EtBr [19] |

| Methylene Blue | Visible light; no special equipment [19] | Suitable, but low sensitivity is a limitation [19] | Simpler disposal due to lower toxicity [19] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: DNA Fragmentation Laddering Assay for Apoptosis Detection

This protocol is designed for the extraction and visualization of fragmented DNA from apoptotic cells to observe the characteristic ladder pattern [1].

Reagents and Materials:

- Cell lysis buffer: 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 5 mM EDTA, 0.2% Triton X-100

- Phenol/Chloroform/Isoamyl Alcohol (25:24:1)

- DNase-free RNase A (10 mg/mL)

- Proteinase K (20 mg/mL)

- Sodium acetate (3 M, pH 5.2)

- Absolute ethanol (ice-cold)

- TE buffer: 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA

- Agarose gel (1.8 - 2.0%)

- DNA stain (e.g., SYBR Safe, EtBr, or Gel Red)

Procedure:

- Harvest and Lyse Cells: Pellet approximately 1-5 x 10⁶ cells by centrifugation. Resuspend the pellet in 0.5 mL of ice-cold lysis buffer and vortex. Incubate on ice for 30 minutes [1].

- Separate Fragmented DNA: Centrifuge the lysate at 27,000 x g for 30 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant contains the fragmented low-molecular-weight DNA, while the pellet contains intact chromatin and nuclei.

- Precipitate DNA: Transfer the supernatant to a new tube. Add 0.5 volumes of 5 M NaCl and vortex. Add 2 volumes of ice-cold absolute ethanol and 0.5 volumes of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2). Mix thoroughly and incubate at -80°C for 1 hour [1].

- Pellet and Wash DNA: Centrifuge at 20,000 x g for 20 minutes to pellet the DNA. Carefully discard the supernatant without disturbing the loose pellet.

- Digest RNA and Proteins: Resuspend the DNA pellet in 400 µL of TE buffer. Add DNase-free RNase A to a final concentration of 20 µg/mL and incubate at 37°C for 30-60 minutes. Then, add Proteinase K to a final concentration of 100 µg/mL and incubate at 65°C overnight (or for several hours) [1].

- Purify DNA: Extract the DNA with an equal volume of Phenol/Chloroform/Isoamyl Alcohol. Centrifuge and transfer the aqueous upper phase to a new tube. Precipitate the DNA with ethanol as in step 3, wash the pellet with 70% ethanol, and air-dry.

- Resuspend and Load DNA: Resuspend the final DNA pellet in 20 µL of TE buffer. Add 2 µL of DNA loading dye (e.g., 0.25% bromophenol blue, 30% glycerol) [1].

- Electrophoresis and Visualization: Load the entire sample onto a 1.8-2.0% agarose gel pre-cast with or post-stained with your chosen DNA stain. Run the gel at 100 V for 40-60 minutes in 1X TAE buffer. Visualize using the appropriate transilluminator (UV for EtBr/Gel Red; blue light for SYBR Safe) [1] [10].

Protocol 2: SURE Electrophoresis for Low-Abundance DNA Samples

The SURE (Successive Reloading) electrophoresis method is invaluable for concentrating highly dilute DNA samples, such as those obtained from limited cell numbers, enabling the detection of faint apoptotic ladders that would otherwise be invisible [22].

Procedure:

- Prepare Sample and Gel: Mix the dilute DNA sample with an appropriate loading dye (with or without SDS). Prepare a standard agarose gel (e.g., 0.8-2.0%, depending on fragment size).

- Initial Loading: Load the maximum volume the well can hold (e.g., 25-35 µL) into the well.

- Apply Brief Electrical Pulse: Immediately connect the power supply and run the gel at a low voltage (e.g., 6 V/cm, or ~84 V for a 14 cm gel) for a short pulse of 20-40 seconds. This pulse drives the DNA from the well into the gel matrix where it stacks at the interface.

- Successive Reloading: Turn off the power supply. Carefully load another identical volume of the same sample into the same well. Repeat the brief electrical pulse.

- Repeat Process: Continue this cycle of loading and pulsing for multiple iterations (e.g., 6-20 times, depending on sample volume and concentration). The DNA from all loadings will stack into a single, concentrated band.

- Complete Electrophoresis: After the final loading, continue electrophoresis at a standard voltage until the tracking dye has migrated sufficiently.

- Stain and Visualize: Stain the gel with a sensitive DNA stain like SYBR Gold or SYBR Safe and visualize. This method can improve detection limits by over 100-fold, allowing visualization of DNA from as few as 30,000 cells [22] [23].

The workflow below summarizes the key steps for detecting apoptosis via DNA laddering, including the SURE electrophoresis concentration step.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for DNA Laddering Detection

A successful DNA fragmentation assay relies on a suite of specialized reagents and equipment. The following table details the core components of the apoptosis researcher's toolkit.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Fragmentation Analysis

| Reagent / Equipment | Function / Purpose | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lysis Buffer | Selectively permeabilizes the plasma membrane to release fragmented DNA while leaving intact nuclei in the pellet. | Contains Triton X-100 or NP-40 in a Tris-EDTA buffer [1]. |

| Nucleic Acid Stains | Binds to DNA fragments, allowing visualization under specific light sources. | SYBR Safe: Safe, sensitive, ideal for cloning [17]. Gel Red: Highly sensitive, requires UV [19]. EtBr: Traditional, hazardous [19]. |

| DNase-free RNase | Degrades RNA in the sample to prevent RNA bands from obscuring the apoptotic DNA ladder pattern. | Essential for a clean background; must be free of DNase activity [1]. |

| Proteinase K | Digests cellular proteins and nucleases that could degrade the DNA sample during isolation. | Added after lysis to ensure complete deproteinization [1]. |

| DNA Ladders/Markers | Provides molecular weight standards for sizing DNA fragments and confirming the apoptotic ladder. | NEB 100 bp/1 kb Ladders: Common for sizing fragments [24]. |

| Blue-Light Transilluminator | Excites safe DNA stains like SYBR Safe; minimizes DNA damage and user exposure to UV light. | Enables downstream cloning from gel-extracted DNA [17] [21]. |

| Phenol/Chloroform | Purifies DNA by removing protein contaminants after cell lysis and digestion. | Critical for obtaining a clean, high-quality DNA sample for visualization [1]. |

The evolution of DNA staining technologies offers researchers powerful choices for detecting apoptosis through DNA fragmentation analysis. While ethidium bromide remains a viable stain for certain applications, its safer alternatives—particularly SYBR Safe and Gel Red—provide excellent sensitivity while mitigating serious risks to both the researcher and the environment. The protocols outlined herein, including the innovative SURE electrophoresis technique, provide a robust framework for reliable detection of apoptotic DNA ladders, even from challenging, low-abundance samples. By selecting modern, non-intercalating stains and appropriate visualization systems, scientists in drug development and basic research can enhance the safety of their laboratories without compromising the quality and reproducibility of their apoptosis data.

Within the broader context of DNA fragmentation laddering detection via gel electrophoresis research, the ability to accurately distinguish programmed cell death (apoptosis) from passive cell death (necrosis) is a cornerstone of cellular biology, oncology, and drug development. Apoptosis is a vital, genetically controlled process that maintains cellular homeostasis, characterized by a series of distinct morphological and biochemical events [1]. Among these, the systematic cleavage of genomic DNA into oligonucleosomal fragments is a definitive hallmark. When separated by gel electrophoresis, this cleavage produces a characteristic "ladder" pattern—a series of bands representing multiples of approximately 180-200 base pairs [1] [25].

In contrast, random DNA degradation, which occurs during necrotic cell death, results from uncontrolled enzymatic breakdown and produces a continuous "smear" of DNA fragments of random sizes on a gel [25]. This application note provides detailed protocols and analytical frameworks for researchers and drug development professionals to correctly execute and interpret the DNA laddering assay, a critical technique for validating apoptotic mechanisms in response to various stimuli or therapeutic agents.

Biochemical Principles and Significance

The Hallmark of Apoptosis: Internucleosomal Cleavage

During the execution phase of apoptosis, a specific endonuclease, often the Caspase-Activated DNase (CAD), is activated. This enzyme cleaves nuclear DNA at the linker regions between nucleosomes, which are core histone complexes around which DNA is wound. The result is the production of DNA fragments whose lengths are multiples of the nucleosomal unit, approximately 180-200 base pairs [1]. This regular, repetitive fragmentation is the molecular origin of the ladder pattern observed after agarose gel electrophoresis.

The Hallmark of Necrosis: Random DNA Degradation

Necrosis, in contrast, is a pathological form of cell death resulting from acute cellular injury. It involves the unregulated release of cellular contents, including non-specific nucleases that digest DNA in a random, non-specific manner. This process generates a heterogeneous mixture of DNA fragments of all sizes, which, upon electrophoresis, appears as a continuous smear from the well to the front of the gel, lacking any discrete bands [25].

The table below summarizes the key differences between these two forms of cell death based on DNA fragmentation patterns.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Apoptotic versus Necrotic DNA Fragmentation

| Feature | Apoptosis (DNA Laddering) | Necrosis (Random Degradation) |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Pattern on Gel | Discrete banding pattern (ladder) at ~180-200 bp intervals | Continuous smear of DNA |

| Underlying Mechanism | Programmed, enzymatic cleavage by CAD at internucleosomal sites | Unregulated, random digestion by released nucleases |

| Biological Process | Active, genetically controlled programmed cell death | Passive, pathological cell death due to injury |

| Cellular Context | Physiological (homeostasis, development) and pathological (chemotherapy) | Pathological (toxicity, ischemia, physical damage) |

Diagram 1: Biochemical Pathways in Cell Death. This flowchart illustrates the decisive biochemical events that lead to distinct DNA fragmentation patterns in apoptosis versus necrosis.

Detailed Experimental Protocol for DNA Fragmentation Analysis

This protocol is adapted from established methods for detecting apoptosis-specific DNA fragmentation [1].

Stage 1: Harvesting and Lysis of Cells

- Steps:

- Pellet approximately 1-5 x 10^6 cells by centrifugation.

- Resuspend the cell pellet thoroughly in 0.5 mL of detergent-based lysis buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris pH 7.4, 5 mM EDTA, 0.2% Triton X-100).

- Vortex the mixture and incubate on ice for 30 minutes to ensure complete cell lysis.

- Centrifuge the lysate at high speed (27,000 x g) for 30 minutes at 4°C. This step separates the fragmented, low-molecular-weight DNA (in the supernatant) from intact, high-molecular-weight DNA and cellular debris (in the pellet).

- Carefully transfer the supernatant, which contains the fragmented DNA, to a new tube. Divide into two 250 µL aliquots.

- Add 50 µL of ice-cold 5 M NaCl to each aliquot and vortex to mix.

Stage 2: Precipitation and Purification of DNA

- Steps:

- To each aliquot, add 600 µL of absolute ethanol and 150 µL of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2). Mix thoroughly by pipetting.

- Incubate the tubes at -80°C for at least 1 hour (or overnight at -20°C) to precipitate the DNA.

- Centrifuge at 20,000 x g for 20 minutes at 4°C to pellet the DNA. Carefully discard the supernatant without disturbing the loose pellet.

- Pool the DNA extracts by re-dissolving the pellets in a total of 400 µL of extraction buffer (10 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA).

- Add 2 µL of DNase-free RNase (10 mg/mL) and incubate for 5 hours at 37°C to remove RNA contamination.

- Add 25 µL of proteinase K (20 mg/mL) and 40 µL of buffer (100 mM Tris pH 8.0, 100 mM EDTA, 250 mM NaCl). Incubate overnight at 65°C to digest proteins.

- Extract DNA with an equal volume of phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1). Centrifuge and transfer the upper aqueous phase to a new tube.

- Precipitate the DNA again with ethanol, centrifuge, and carefully discard the final supernatant.

Stage 3: Agarose Gel Electrophoresis and Visualization

- Steps:

- Air-dry the DNA pellet and resuspend it in 20 µL of Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) buffer supplemented with 2 µL of DNA loading dye (e.g., 0.25% bromophenol blue, 30% glycerol).

- Separate the DNA fragments electrophoretically on a 2% agarose gel prepared in TAE buffer and containing a fluorescent nucleic acid stain, such as ethidium bromide (1 µg/mL) or a safer alternative like SYBR Green.

- Load the DNA ladder (marker) and experimental samples into the wells. Run the gel at 5-8 V/cm until the dye front has migrated sufficiently.

- Visualize the DNA bands using an ultraviolet transillumination system and document the image.

Diagram 2: DNA Laddering Assay Workflow. A step-by-step visual guide to the protocol for isolating and visualizing apoptotic DNA fragmentation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Laddering Assays

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example / Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lysis Buffer | Disrupts cell membrane and releases cellular contents, including fragmented DNA. | Typically contains Tris (pH 7.4), EDTA, and a detergent like Triton X-100 or NP-40 [1]. |

| RNase A (DNase-free) | Degrades RNA that would otherwise contaminate the DNA sample and obscure the gel results. | Must be certified DNase-free to prevent degradation of the DNA fragments of interest [1]. |

| Proteinase K | A broad-spectrum serine protease that digests nucleases and other proteins, protecting DNA from degradation. | Incubation at elevated temperature (e.g., 65°C) enhances activity [1]. |

| Phenol/Chloroform/Isoamyl Alcohol | Used for liquid-liquid extraction to remove protein contaminants from the DNA sample. | The mixture denatures and partitions proteins into the organic phase, leaving DNA in the aqueous phase [1]. |

| Agarose | A polysaccharide polymer that forms a porous gel matrix for the size-based separation of DNA fragments. | 2% concentration is ideal for resolving small DNA fragments (100-2000 bp) typical of apoptosis [1] [26]. |

| DNA Gel Stain | Intercalates with double-stranded DNA, allowing visualization under specific light. | Ethidium bromide is traditional; SYBR Green I is a highly sensitive alternative [27] [28]. |

| DNA Ladder/Marker | A mixture of DNA fragments of known sizes, used as a reference to estimate the size of experimental fragments. | A 50 bp or 100 bp ladder is suitable for confirming the ~200 bp interval banding pattern [27] [28]. |

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Visual Pattern Recognition

The primary mode of analysis is the visual inspection of the stained gel.

- Positive Apoptosis Indication: A clear ladder of bands, where the smallest band is around 180-200 bp, and successive bands are multiples of this size (e.g., ~400 bp, ~600 bp, etc.) [1] [25].

- Necrosis Indication: A diffuse, continuous smear of DNA with no distinct bands, indicating random fragmentation.

- Negative Result: A single, high-molecular-weight band remaining in the well, indicating an absence of significant DNA fragmentation.

Advanced and Quantitative Analysis Methods

While the standard gel is semi-quantitative, modern computational and technological advances enable more robust analysis.

- Digital Image Analysis: Software tools like GelGenie, an AI-powered framework, can automatically identify gel bands in seconds, surpassing the capabilities of traditional software in both ease-of-use and versatility [29]. These tools use segmentation to classify pixels as 'band' or 'background,' providing a more quantitative assessment of band intensity and position.

- Electropherogram Conversion: Advanced image processing algorithms can convert conventional agarose gel images into capillary electrophoresis (CE)-like fluorescence profiles. This involves steps like median filtering to remove background noise and pixel-wise intensity summation along the migration axis to generate one-dimensional records [28]. Each DNA band is transformed into a distinct fluorescence peak, facilitating more precise quantification of fragment size and relative abundance.

- Electrochemical Analysis: Emerging techniques use label-free differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) with carbon nanotube-modified electrodes to measure DNA oxidation signals. This method can detect differences in the electrochemical behavior of native supercoiled DNA versus fragmented DNA, providing a promising platform for high-throughput screening that complements traditional gel electrophoresis [30].

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Issues in DNA Laddering Assays

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or absent DNA ladder | Insufficient apoptosis; poor DNA recovery; low cell number. | Include a positive control (e.g., cells treated with a known apoptosis inducer); ensure careful handling during precipitation steps. |

| DNA smear with a ladder | Significant necrosis occurring alongside apoptosis; sample degradation. | Optimize treatment conditions and timing to favor pure apoptosis; ensure all reagents are fresh and samples are processed quickly. |

| No DNA in gel | Complete loss of DNA pellet during precipitation; inefficient lysis. | Centrifuge at recommended speeds; be extremely careful when discarding supernatant after precipitation steps. |

| High background smear | Incomplete protein digestion or RNA contamination. | Use fresh proteinase K and ensure adequate incubation time; use DNase-free RNase. |

Complementary and Advanced Techniques

For a comprehensive analysis of apoptosis, the DNA laddering assay should be used in conjunction with other techniques that probe different stages of the cell death process.

- TUNEL Assay (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP Nick End Labeling): Detects DNA strand breaks by labeling the 3'-ends of fragmented DNA with a fluorescent tag. It is more sensitive than the DNA ladder assay and can be used for in situ detection in tissues [1].

- Analysis of PARP1 Cleavage: During caspase-dependent apoptosis, the full-length 116 kDa DNA-repair protein PARP1 is cleaved into 89 and 24 kDa fragments. Detecting this cleavage by Western blot or advanced single-cell assays (like the SEVAP assay) serves as a key biochemical marker upstream of DNA fragmentation [27].

- Annexin V Staining: Used with flow cytometry, it detects the externalization of phosphatidylserine on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, an early event in apoptosis [1].

- Single-Cell Electrophoresis (Comet Assay): Excellent for detecting early DNA damage at the level of individual cells, revealing heterogeneity in cell populations that bulk DNA laddering might miss [27].

Step-by-Step Protocols: From Sample Preparation to High-Resolution Detection

Within the context of DNA fragmentation laddering detection, a cornerstone technique in apoptosis research and drug development, optimized agarose gel electrophoresis is paramount. The characteristic DNA ladder, consisting of fragments in approximately 180-200 base pair multiples, results from internucleosomal cleavage during programmed cell death [31] [1]. Successful resolution of this ladder pattern is highly dependent on two critical factors: the concentration of the agarose gel and the composition of the running buffer [5] [32]. This application note provides detailed protocols and data-driven guidelines to optimize these parameters for clear, reliable detection of DNA fragmentation, enabling researchers and drug development professionals to accurately assess cellular responses to therapeutic agents.

The Role of DNA Fragmentation in Apoptosis

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is a genetically controlled process essential for development and tissue homeostasis. A biochemical hallmark of late-stage apoptosis is the cleavage of nuclear DNA into oligonucleosomal fragments by activated endonucleases, such as Caspase-Activated DNase (CAD) [31] [1]. When separated by size via agarose gel electrophoresis, these fragments produce a distinctive "ladder" pattern, which differs markedly from the smeared pattern observed in necrotic cell death [1]. This protocol is widely used in cancer research and toxicology to evaluate the efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents and to study disease mechanisms by confirming the induction of apoptosis [1].

Table: Key Characteristics of Apoptotic DNA Fragmentation

| Feature | Description | Significance in Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Fragment Size | Multiples of ~180-200 base pairs [1] | Creates a laddering pattern on a gel. |

| Enzyme Responsible | Caspase-Activated DNase (CAD) [31] | A specific biochemical marker of apoptosis. |

| Pattern on Gel | Discrete bands forming a ladder [1] | Distinguishes apoptosis from necrosis (smear). |

| Stage of Apoptosis | Mid to late event [1] | Useful for confirming execution-phase cell death. |

Diagram Title: Biochemical Pathway to DNA Ladder Formation in Apoptosis

Critical Factors for Gel Optimization

Agarose Gel Concentration

The concentration of agarose determines the pore size of the gel matrix, which directly controls the resolution of DNA fragments. Using the correct percentage is critical for distinguishing the closely spaced bands of an apoptosis ladder [32]. Lower percentages are optimal for separating larger DNA fragments, while higher percentages provide better resolution for smaller fragments.

Table: Agarose Concentration Guidelines for DNA Fragment Separation

| Agarose Percentage (%) | Optimal Separation Range for DNA (bp) | Suitability for Apoptosis Ladder (Key Band Sizes) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.7% | 1,000 - 20,000 bp [6] | Low (Fragments > 1,000 bp) |

| 1.0% | 500 - 10,000 bp [6] | Medium (Core ladder ~180-1,000 bp) |

| 1.5% | 300 - 3,000 bp [32] | High (Ideal for ~180, 360, 540 bp, etc.) |

| 2.0% | 100 - 2,000 bp [32] [6] | Very High (Excellent resolution of lower bands) |

| 2.5% - 3.0% | 50 - 1,000 bp [32] | Medium (May not resolve higher multiples well) |

For the detection of DNA fragmentation ladders, a 1.5% to 2.0% agarose gel is generally recommended, as it provides the best resolution for the critical fragments in the 180-2000 bp range [1].

Electrophoresis Buffer Selection

The choice between the two common running buffers, TAE (Tris-Acetate-EDTA) and TBE (Tris-Borate-EDTA), influences DNA migration, resolution, and buffer capacity [5].

Table: Comparison of TAE and TBE Running Buffers

| Parameter | TAE Buffer | TBE Buffer |

|---|---|---|

| Migration Speed | Faster [5] | ~10% slower than TAE [5] |

| Resolution of Large Fragments | Better (Typically for fragments >1 kb) [5] | Good |

| Resolution of Small Fragments | Good | Better [5] |

| Buffer Capacity | Lower (Not suitable for long runs) [5] | Higher (Suitable for long runs) [5] |

| Compatibility with Enzymatic Steps | Yes (Recommended for preparative gels) [5] | No (Not recommended for applications involving enzymatic steps) [5] |

| Recommended Use | Standard analytical and preparative gels [33] [6] | Gels requiring high resolution of small fragments or long run times [5] |

For DNA laddering detection, TAE buffer is sufficient for most applications. However, if sharper band definition is required, particularly for the smallest fragments, TBE buffer is the superior choice [5].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Preparing a 2% Agarose Gel for High-Resolution DNA Laddering

This protocol is optimized for the clear visualization of apoptotic DNA fragmentation patterns [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Agarose Powder | Forms the sieving gel matrix [6] | Use standard LE Agarose [22]. |

| TAE or TBE Buffer | Running buffer provides ionic conductor [5] | 1x concentration for gel and tank [6]. |

| DNA Ladder | Sizing standard for base pairs [33] | e.g., 100 bp ladder, 1 kb DNA Ladder [33]. |

| Loading Dye | Adds color & density for well loading [5] | Contains tracking dyes (e.g., bromophenol blue) [6]. |

| Nucleic Acid Stain | Visualizes DNA under UV/blue light [33] | SYBR Safe, Ethidium Bromide [33] [6]. |

| Gel Electrophoresis System | Holds gel and buffer for the run [34] [35] | Includes casting tray, comb, tank, power supply. |

| Microwave/Hot Plate | Melts agarose in buffer [6] | Creates a homogeneous gel solution. |

| UV Imager | Visualizes and documents results [33] | Gel documentation system or transilluminator. |

Procedure:

- Combine and Melt: Weigh 2.0 g of agarose powder and add it to 100 mL of 1x TAE or TBE buffer in a microwavable flask [6].

- Dissolve Agarose: Heat the mixture in a microwave using short bursts (30-45 seconds), swirling intermittently, until the solution is completely clear and no translucent particles remain [33] [6]. Use caution to avoid boil-overs.

- Cool and Add Stain: Allow the molten agarose to cool on the bench until it is comfortable to touch (approximately 50-60°C) [6]. Then, add the nucleic acid stain as required. For SYBR Safe, use a 1:10,000 dilution (e.g., 10 µL of 10,000x stock into 100 mL gel) [33].

- Cast the Gel: Place the comb in the casting tray. Pour the molten agarose into the tray, ensuring it is on a level surface. Use a pipette tip to push any bubbles to the edge of the tray [33] [6].

- Solidify: Allow the gel to solidify completely at room temperature for 20-30 minutes. It will appear opaque and firm when ready [6].

- Prepare and Load Samples:

- Mix DNA samples with loading dye to a final 1x concentration [33]. For apoptotic DNA extracts, the final resuspension volume is typically 20 µL [1].

- Once solidified, place the gel in the electrophoresis chamber and cover it completely with 1x running buffer (3-5 mm above the gel surface) [5] [6].

- Carefully remove the comb.

- Slowly load your DNA ladder and prepared samples into the wells [6].

- Run Electrophoresis: Connect the lid, ensuring the black (negative) electrode is at the well end and the red (positive) electrode is at the opposite end. Run the gel at 80-150 V until the dye front has migrated 75-80% of the way down the gel [33] [6]. To minimize "smiling" effects and improve band sharpness, running at a lower voltage for a longer time is often beneficial [5].

- Visualize: Turn off the power supply, remove the gel from the tank, and visualize the DNA bands using a UV or blue light transilluminator [33] [6].

Diagram Title: Agarose Gel Electrophoresis Workflow

Advanced Method: SURE Electrophoresis for Dilute Samples

Detecting DNA ladders from highly dilute apoptotic samples can be challenging. The Successive Reloading (SURE) electrophoresis method allows for concentrating samples directly within the gel well [22].

Procedure:

- Prepare a standard agarose gel as described in Section 4.1.

- Load a small volume (e.g., 15-25 µL) of the dilute DNA sample mixed with loading dye into the well.

- Connect the power supply and apply a low electric field (approximately 6 V/cm, e.g., 84 V for a 14 cm gel) for a brief pulse of 20-40 seconds [22].

- Turn off the power, disconnect the leads, and carefully load another aliquot of the same sample into the same well.

- Repeat steps 3 and 4 for multiple cycles (e.g., 6-20 times). The DNA from each loading stacks into a single, concentrated band with minimal broadening [22].

- After the final loading, complete the electrophoresis run as usual.

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

- Poor Band Resolution or Smiling Effect: This can be caused by uneven heating due to high voltage. To resolve this, run the gel at a lower voltage for a longer duration [5]. Also, ensure the gel concentration is optimal for the expected fragment size (refer to Table 2) [32].

- Faint or No Bands: This indicates insufficient DNA. For ethidium bromide or SYBR Safe staining, load at least 20 ng of DNA per band. If samples are dilute, employ the SURE electrophoresis method [5] [22].

- Band Distortion or Melting Gel: This is often due to an insufficient amount of running buffer. Always ensure the gel is fully submerged with 3-5 mm of buffer covering its surface [5].

- Masked Bands: If a band of interest co-migrates with a tracking dye (e.g., a 50 bp fragment with Orange G), it may be obscured. Select a loading dye with tracking dyes that migrate outside your fragment size of interest [5].

Within the context of DNA fragmentation laddering detection research, the selection of an appropriate DNA ladder is a critical pre-analytical step that fundamentally underpins the validity and interpretability of experimental data. DNA ladders, also known as molecular weight rulers, serve as essential reference standards during gel electrophoresis, enabling researchers to determine the size of unknown DNA fragments by comparison to a series of molecules with known lengths [36]. In studies of programmed cell death and other fragmentation phenomena, the precise sizing of DNA fragments is paramount, as the distinctive "laddering" pattern—a hallmark of internucleosomal cleavage—can be obscured or misinterpreted without proper molecular weight calibration [37]. This application note provides a structured framework for selecting optimal DNA ladders and details standardized protocols to ensure reproducible and accurate analysis of DNA fragmentation.

The Critical Role of DNA Ladders in Fragmentation Analysis

In DNA fragmentation research, the electrophoretic separation pattern provides crucial diagnostic information. A smear of randomly sized fragments often indicates necrosis, while a regular ladder of fragments differing by approximately 180-200 base pairs confirms apoptosis due to cleavage at internucleosomal regions [37]. The DNA ladder acts as the quantitative ruler against which these patterns are measured, making its proper selection fundamental to accurate experimental outcomes.

The utility of DNA ladders extends beyond mere size determination. They serve as internal controls that indicate whether the gel electrophoresis process has functioned correctly, based on the sharpness and expected position of the reference bands [36]. Furthermore, certain specialized ladders enable approximate quantification of DNA amounts in sample bands, providing additional analytical dimensions beyond simple fragment sizing [36]. When investigating low-template DNA (LTDNA) samples—common in clinical and forensic applications—the ladder becomes even more critical for interpreting stochastic effects such as allele dropout and heterozygote imbalance that can complicate fragmentation analysis [37].

DNA Ladder Selection Guide

Comprehensive Comparison of DNA Ladder Products

Table 1: Comparison of Major DNA Ladder Types and Their Applications in Fragmentation Research

| Ladder Type/Product | Size Range | Key Features | Optimal Applications in Fragmentation Research | Supplier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GeneRuler DNA Ladder | Wide range depending on specific product | Chromatography-purified fragments; sharp bands; can be run at high voltages | General purpose DNA sizing; validation of apoptosis laddering patterns; suitable for various gel percentages | Thermo Fisher [36] |

| O'RangeRuler DNA Ladder | Step ladders with basic unit repeats (10, 15, 20, 50, 100, 200, or 500 bp) | Higher density of bands at specific size ranges; evenly spaced reference bands | Precise sizing of DNA fragments in specific size ranges; optimal for resolving nucleosomal multimers | Thermo Fisher [36] |

| MassRuler DNA Ladder | Low Range (LR) and High Range (HR) formats | Designed for accurate DNA quantification on gels; mass proportional to fragment size | Quantifying fragment abundance in addition to sizing; assessing sample degradation levels | Thermo Fisher [36] |

| FastRuler DNA Ladder | Optimized for PCR product sizes | Fast separation (8-14 min); short separation distance (10-20 mm) | Rapid assessment of DNA integrity; high-throughput applications | Thermo Fisher [36] |

| ZipRuler Express DNA Ladder | 100-20,000 bp | Split into two ladders run in neighboring lanes; broad range with high resolution | Comprehensive analysis of complex fragmentation patterns across wide size spectrum | Thermo Fisher [36] |

| Conventional DNA Markers | Up to 23 kb (NEB); up to 48.5 kb (Thermo Fisher) | Digest of lambda, phage, or plasmid DNA; traditional standards | Analysis of large DNA fragments; genomic DNA integrity assessment | NEB, Thermo Fisher [38] [36] [39] |

| PFG Markers | 1.5-1,018 kb (NEB) | Specifically designed for pulsed-field gel electrophoresis | Analysis of very large DNA fragments; chromosome-sized fragments | NEB [38] [39] |

| 50 bp DNA Ladder | 50-1000 bp (NEB) | Intense reference bands at 500/300 bp; ideal for percentage gels | High-resolution analysis of nucleosomal laddering patterns; precise sizing of small fragments | NEB [39] |

| Low Molecular Weight DNA Ladder | <1000 bp | Optimized for small fragment separation | Apoptosis detection; fine mapping of oligonucleosomal fragments | NEB [39] |