DNA Laddering vs. TUNEL Assay: A Definitive Guide to Specificity in Apoptosis Detection

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of two fundamental techniques for detecting DNA fragmentation: the DNA laddering assay and the TUNEL assay.

DNA Laddering vs. TUNEL Assay: A Definitive Guide to Specificity in Apoptosis Detection

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of two fundamental techniques for detecting DNA fragmentation: the DNA laddering assay and the TUNEL assay. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles, specific methodologies, and optimal applications of each technique. The scope extends from core biochemical concepts to advanced troubleshooting and validation strategies, addressing common pitfalls like the non-specificity of TUNEL and the sensitivity limitations of DNA laddering. By synthesizing current research and practical insights, this guide empowers scientists to select and optimize the most appropriate method for their specific research context, from basic life sciences to preclinical drug development.

The Biochemistry of Cell Death: Understanding DNA Fragmentation

Internucleosomal DNA cleavage is a definitive biochemical hallmark of apoptotic cell death, setting it apart from other forms of cellular demise. This process is orchestrated by caspase-activated DNase (CAD), which systematically cleaves chromosomal DNA into 180-200 base pair fragments corresponding to the length of DNA wrapped around nucleosomes [1]. These fragments, when separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, generate the characteristic "DNA ladder" that has become a visual signature of apoptosis [2] [3]. The detection of this specific fragmentation pattern serves as a critical endpoint in cellular life-and-death decisions, with profound implications for understanding development, tissue homeostasis, and diseases such as cancer [4] [3].

The molecular machinery governing this process involves a carefully coordinated cascade. In healthy cells, CAD remains inactive through binding to its inhibitor (ICAD). Upon initiation of apoptosis, executioner caspases (particularly caspase-3) cleave ICAD, liberating CAD to enter the nucleus and execute DNA cleavage at internucleosomal regions [1]. This systematic fragmentation represents one of the final commitments to cellular suicide, preventing the propagation of genetically compromised cells.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of the two principal methodologies used to detect this apoptotic hallmark: the classical DNA ladder assay and the TUNEL (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP Nick End Labeling) technique. We evaluate their technical principles, experimental protocols, performance characteristics, and applications to empower researchers in selecting the optimal approach for their specific experimental context.

Methodological Principles and Comparative Analysis

DNA Ladder Assay: A Classical Approach

The DNA ladder assay represents the historical gold standard for apoptosis detection, relying on the separation of extracted DNA fragments using standard agarose gel electrophoresis. This method directly visualizes the characteristic nucleosomal fragmentation pattern through conventional DNA staining techniques [2] [3].

Table 1: DNA Ladder Assay Technical Profile

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Agarose gel separation of extracted DNA fragments |

| Target | Internucleosomal DNA fragments (180-200 bp multiples) |

| Readout | Visual ladder pattern on gel |

| Sensitivity | Requires ~10⁶ apoptotic cells [3] |

| Temporal Resolution | Late apoptosis detection |

| Key Advantage | Direct visualization of apoptotic hallmark; cost-effective |

| Primary Limitation | Lower sensitivity; cannot analyze single cells |

TUNEL Assay: A Modern Molecular Technique

The TUNEL assay operates on a fundamentally different principle, enzymatically detecting the 3'-OH termini of DNA breaks generated during apoptosis. The technique utilizes terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) to incorporate labeled nucleotides (e.g., fluorescein-dUTP) at DNA break sites, allowing visualization through fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry [1] [5].

Table 2: TUNEL Assay Technical Profile

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Enzymatic labeling of DNA strand breaks |

| Target | 3'-OH ends in single- and double-stranded DNA breaks |

| Readout | Fluorescence microscopy, flow cytometry, or chromogenic detection |

| Sensitivity | Can detect individual apoptotic cells [1] |

| Temporal Resolution | Can detect earlier stages than DNA laddering |

| Key Advantage | Single-cell resolution; high sensitivity; tissue localization |

| Primary Limitation | Less specific for apoptosis (labels any DNA breaks) |

Experimental Protocols and Technical Considerations

DNA Ladder Assay: Updated Protocol

Recent methodological refinements have improved the reliability and efficiency of the DNA ladder assay. The following protocol, adapted from Saadat et al. (2015), provides a robust framework for apoptosis detection in mammalian cells [2] [3]:

Cell Culture and Apoptosis Induction:

- Culture NIH-3T3 cells (or relevant cell line) in appropriate medium (e.g., RPMI1640 with 10% FBS).

- Induce apoptosis using 500 μM H₂O₂ for 48 hours [3].

- Critical Note: Collect both adherent and floating cells, as apoptotic cells detach and would be lost if only adherent cells are harvested [3].

DNA Extraction Protocol:

- Centrifuge culture media (containing detached apoptotic cells) at 5,000 rpm for 5 minutes. Discard supernatant.

- Add 500 μL lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 20 mM EDTA, 1.4M NaCl, 2% CTAB) to cell pellet.

- Add 500 μL additional lysis buffer to culture vessel, incubate 10 minutes at room temperature, and combine with cell pellet.

- Incubate lysate at 65°C for 5 minutes, then cool to room temperature.

- Add 700 μL chloroform-isoamyl alcohol, mix gently, and centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 5 minutes.

- Transfer aqueous phase to new tube, add equal volume cold isopropanol, and mix by inversion.

- Centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 5 minutes, discard supernatant, and air-dry pellet for 30 minutes.

- Resuspend DNA in 50 μL distilled water and quantify using spectrophotometry [3].

Gel Electrophoresis and Visualization:

- Load 1-2 μg DNA per lane on 1.5% agarose gel containing SYBR-Safe DNA gel stain (1 μL/100 mL gel).

- Conduct electrophoresis at constant voltage (5-6 V/cm gel length) until adequate separation achieved.

- Visualize using UV transillumination system; apoptotic samples display characteristic 180-200 bp ladder pattern [3].

TUNEL Assay: Standardized Protocol

The TUNEL protocol has evolved with variations in detection methodology. The following represents a consensus approach optimized for sensitivity and specificity:

Sample Preparation:

- For cells: Fix with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15-20 minutes at room temperature.

- For tissue sections: Deparaffinize and rehydrate FFPE sections using standard protocols.

- Critical Consideration: Antigen retrieval method significantly impacts protein antigenicity for multiplexing. Proteinase K digestion diminishes protein antigenicity, while pressure cooker treatment preserves it without compromising TUNEL sensitivity [5].

DNA Break Labeling:

- Permeabilize cells with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5-10 minutes on ice.

- Prepare TUNEL reaction mixture according to manufacturer's instructions, containing:

- Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) enzyme

- Fluorescein-labeled dUTP (or alternative modified nucleotide)

- Reaction buffer with cobalt cofactor

- Incubate samples with TUNEL reaction mixture for 60 minutes at 37°C in a humidified chamber.

- Wash with PBS to terminate reaction.

Detection and Analysis:

- For fluorescence detection: Analyze directly by fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry.

- For brightfield applications: incubate with anti-fluorescein antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase, followed by DAB chromogenic development [1].

- Counterstain with DAPI (for fluorescence) or methyl green/methyl blue (for chromogenic detection) to visualize total cells.

Specificity Controls:

- Include DNase-treated positive control samples.

- Include negative controls omitting TdT enzyme.

- Enhanced Specificity: For improved apoptosis specificity, combine TUNEL with caspase-3 immunostaining to confirm activation of apoptotic pathways [1].

Comparative Performance and Applications

Sensitivity and Specificity Analysis

The fundamental distinction between these techniques lies in their detection thresholds and specificity profiles. The DNA ladder assay requires approximately 10⁶ apoptotic cells for clear visualization, making it unsuitable for analyzing small cell populations or rare events [3]. In contrast, TUNEL can detect DNA fragmentation in individual cells, providing significantly higher sensitivity for heterogeneous populations or limited sample material [1].

Regarding specificity, while both techniques detect apoptotic DNA fragmentation, TUNEL exhibits broader reactivity to various DNA breaks. As noted in recent studies, "TUNEL staining is not always a specific indicator of apoptosis because cells actively repairing DNA damage or undergoing necrosis can also incorporate labeled nucleotides" [1]. This limitation can be mitigated through dual-labeling approaches combining TUNEL with caspase-3 detection [1] or careful morphological analysis.

Technical Comparison and Selection Guidelines

Table 3: Method Selection Guide for Apoptosis Detection

| Experimental Requirement | Recommended Method | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Initial apoptosis screening | DNA ladder assay | Cost-effective; simple interpretation; establishes apoptotic hallmark |

| Single-cell analysis | TUNEL assay | Single-cell resolution; compatible with flow cytometry |

| Tissue localization studies | TUNEL assay | Preserves spatial context; in situ application |

| Multiplexed protein detection | TUNEL with pressure cooker retrieval | Preserves protein antigenicity for spatial proteomics [5] |

| Early apoptosis detection | TUNEL assay | Detects DNA breaks before complete nucleosomal fragmentation |

| Resource-limited settings | DNA ladder assay | Minimal equipment requirements; lower cost |

| High-throughput screening | TUNEL with flow cytometry | Automated quantification; rapid analysis |

Advanced Applications and Integration

Multiplexed Approaches and Spatial Context

Recent methodological advances have enhanced TUNEL compatibility with cutting-edge techniques. Sherman et al. (2025) demonstrated that replacing proteinase K with pressure cooker antigen retrieval enables seamless TUNEL integration with multiple iterative labeling by antibody neodeposition (MILAN) and cyclic immunofluorescence (CycIF) [5]. This harmonization permits rich spatial contextualization of cell death within complex tissues while simultaneously mapping dozens of protein targets, opening new frontiers in microenvironmental analysis of apoptosis.

Apoptosis Detection in Specific Research Contexts

The choice between detection methods varies significantly across research applications:

Cancer Research: The DNA ladder assay provides compelling visual evidence of drug-induced apoptosis in therapeutic development [3]. Modified protocols have optimized DNA extraction to minimize sample loss, enhancing detection reliability [2]. For screening compound libraries, TUNEL with flow cytometry enables high-throughput quantification of apoptotic responses.

Male Infertility Studies: Sperm DNA fragmentation represents a specialized application where TUNEL has demonstrated particular utility. Comparative studies indicate TUNEL detects higher amounts of DNA fragmentation during cryopreservation compared to SCSA, SCD, and COMET assays [6] [7]. Standardized TUNEL protocols have established clinical cut-off values (9.17%) for distinguishing fertile and infertile samples [8].

Developmental Biology: The spatial resolution of TUNEL makes it indispensable for mapping programmed cell death during embryogenesis and tissue remodeling. Recent protocol innovations maintain tissue architecture while enabling multiplexed protein detection alongside DNA fragmentation analysis [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Apoptosis Detection

| Reagent/Catalog Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) | Catalyzes addition of labeled nucleotides to 3'-OH ends of DNA breaks | Critical for TUNEL assay; requires cobalt cofactor [1] |

| Biotin- or fluorescein-dUTP | Modified nucleotides for incorporation at DNA break sites | Fluorescein-dUTP enables direct fluorescence detection; biotin-dUTP requires secondary detection [1] |

| Caspase-activated DNase (CAD) | Endonuclease executing internucleosomal cleavage | Molecular mediator of DNA laddering; useful as apoptosis marker [1] |

| Anti-caspase-3 antibodies | Detection of activated executioner caspase | Confirm apoptotic pathway activation; enhances TUNEL specificity [1] |

| SYBR-Safe DNA gel stain | Fluorescent DNA intercalating dye | Safer alternative to ethidium bromide for DNA ladder visualization [3] |

| Proteinase K | Proteolytic enzyme for antigen retrieval | Traditional TUNEL protocol component; degrades protein epitopes [5] |

| Pressure cooker system | Heat-mediated antigen retrieval | Alternative to Proteinase K; preserves protein antigenicity for multiplexing [5] |

Molecular Pathway of Apoptotic DNA Fragmentation

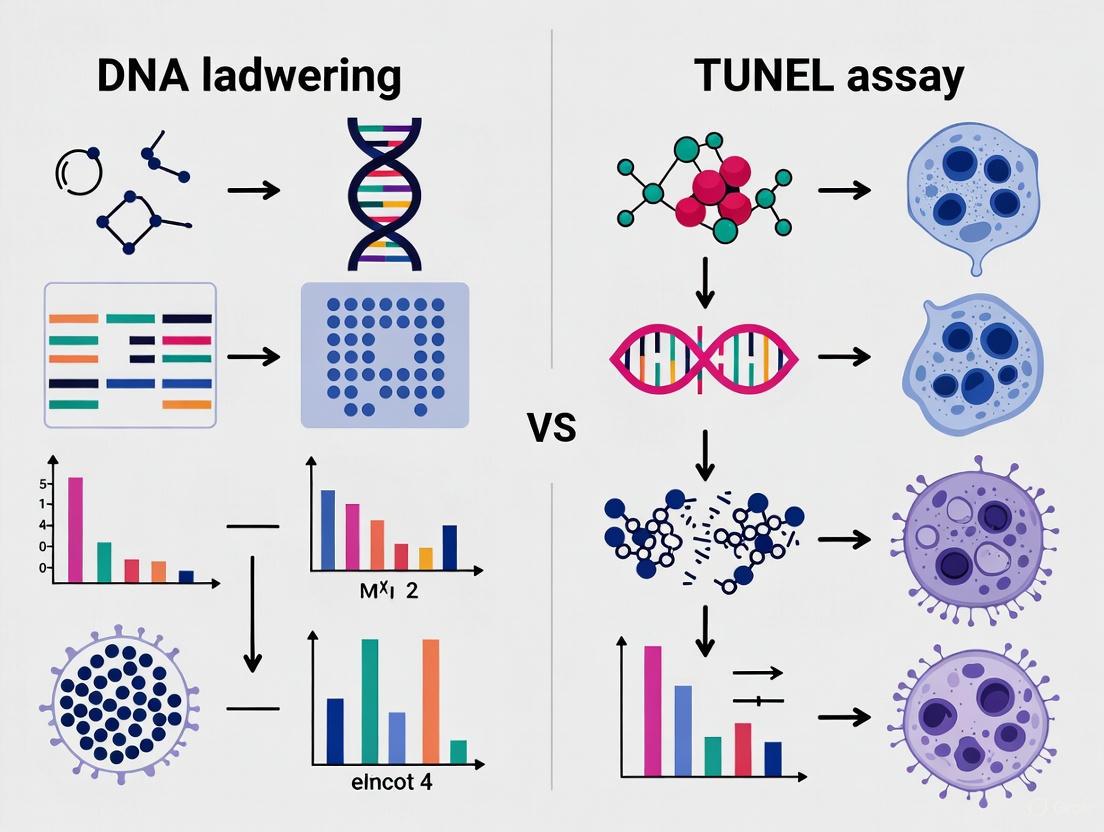

The following diagram illustrates the molecular events leading to internucleosomal DNA cleavage and the detection points for each method:

Diagram 1: Molecular Pathway of Apoptotic DNA Fragmentation and Detection

Experimental Workflow Comparison

The following diagram compares the procedural workflows for both detection methods:

Diagram 2: Comparative Workflows for DNA Ladder and TUNEL Assays

The detection of internucleosomal DNA cleavage remains a cornerstone of apoptosis research, with both DNA laddering and TUNEL offering complementary approaches for different experimental contexts. The DNA ladder assay provides an economical, straightforward method for establishing the apoptotic hallmark, particularly suitable for initial screening and resource-limited settings. In contrast, TUNEL offers superior sensitivity, single-cell resolution, and spatial context preservation, making it indispensable for advanced applications requiring quantification, localization, or multiplexing.

Recent methodological refinements in both techniques – from optimized DNA extraction protocols for ladder assays to pressure cooker-based antigen retrieval for TUNEL – have enhanced their reliability and expanded their applications. The choice between methods should be guided by specific experimental requirements including sample type, required sensitivity, equipment availability, and need for multiplexing capabilities. As apoptosis research continues to evolve, both techniques will maintain their relevance as fundamental tools for defining this critical molecular hallmark of programmed cell death.

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is a fundamental biological process crucial for development, tissue homeostasis, and defense against disease. Its dysregulation is implicated in various pathologies, including cancer and neurodegenerative disorders [9]. Among the most recognizable biochemical hallmarks of apoptosis is DNA laddering—the internucleosomal cleavage of nuclear DNA into fragments of roughly 180 base pairs and multiples thereof [10] [11]. This distinctive ladder pattern, visualized via agarose gel electrophoresis, has served as a classic signature of apoptotic cell death for decades. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison between the DNA laddering assay and the TUNEL (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP Nick End Labeling) method, framing them within ongoing research on fragmentation detection.

The Biochemical Mechanism of DNA Laddering

The formation of the DNA ladder is a caspase-dependent process executed by specific enzymatic machinery.

The CAD/ICAD Enzyme System

The primary enzyme responsible for apoptotic DNA fragmentation is Caspase-Activated DNase (CAD), also known as DFF40 (DNA Fragmentation Factor 40) [10]. In healthy, non-apoptotic cells, CAD remains complexed with its inhibitor, ICAD (Inhibitor of CAD). ICAD acts as a specific chaperone for CAD and keeps it in an inactive state [10].

During apoptosis, the apoptotic effector caspase, caspase-3, is activated and cleaves ICAD. This cleavage dissociates the CAD-ICAD complex, liberating and activating CAD [10]. The activated CAD enzyme then cleaves chromosomal DNA at the internucleosomal linker regions between nucleosomes. These are the protein-containing structures that occur in chromatin at approximately 180-base-pair intervals [10]. Because the DNA is tightly wrapped around the nucleosomes' core histones, the linker sites are the most exposed and accessible regions for CAD to attack. This systematic cleavage results in the characteristic DNA fragments that form the "ladder" on an agarose gel [10].

Diagram 1: The CAD/ICAD Apoptotic DNA Fragmentation Pathway

DNA Laddering vs. TUNEL Assay: A Head-to-Head Comparison

The following table provides a detailed, objective comparison of the DNA laddering assay and the TUNEL assay, two principal methods for detecting apoptotic DNA fragmentation.

| Feature | DNA Laddering Assay | TUNEL Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Agarose gel electrophoresis of internucleosomal DNA fragments [10] [11] | Enzymatic labeling of 3'-OH ends of DNA breaks with modified dUTP [11] |

| Specificity for Apoptosis | High for late apoptosis (characteristic ladder pattern) [12] | Can label any DNA break, including necrosis; requires careful interpretation [12] |

| Sensitivity | Low to moderate; requires ~5-10% apoptotic cells [12] | High; can detect single apoptotic cells [11] |

| Stage of Apoptosis Detected | Late stage (after caspase activation) [12] | Mid to late stage [12] |

| Throughput & Scalability | Low; suitable for bulk cell population analysis [12] | High; adaptable to flow cytometry for rapid, single-cell analysis [11] |

| Quantification Capability | Semi-quantitative [12] | Quantitative (especially via flow cytometry) [11] |

| Key Advantage | Provides iconic, visual hallmark of apoptosis; cost-effective [3] [12] | High sensitivity and versatility for in-situ detection and quantification [11] |

| Key Limitation | Less sensitive; not suitable for single-cell analysis or tissue sections [12] | Potential for false positives from necrotic DNA fragmentation [12] |

| Typical Cost | Low (standard lab reagents) [3] | High (commercial kits often required) [13] |

Experimental Protocols for Apoptosis Detection

Detailed Protocol: DNA Laddering Assay

This is an improved protocol for detecting apoptosis via DNA laddering in mammalian cells, adapted from research that optimized the method for ease and reliability [3].

Cell Lysis and DNA Extraction

- Harvest Cells: Collect both adherent and floating cells by centrifugation. Critical Hint: Apoptotic cells detach, so collecting the culture medium is crucial to avoid losing the majority of apoptotic cells [3].

- Lyse Cells: Resuspend the cell pellet in 500 μL of lysis buffer (e.g., 2% buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.2% Triton X-100) [3] [12]. Incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes [3].

- Separate Fragmented DNA: Centrifuge the lysate at 12,000-27,000 x g for 5-30 minutes. The fragmented DNA will be in the supernatant, while intact chromatin and cell debris are in the pellet [3] [12].

- Precipitate DNA: Transfer the supernatant to a new tube. Add an equal volume of cold isopropanol and 0.1-0.15 volumes of sodium acetate (pH 5.2) to precipitate the DNA. Incubate at -80°C for 1 hour [3] [12].

- Pellet DNA: Centrifuge at 12,000-20,000 x g for 5-20 minutes. Discard the supernatant and air-dry the pellet [3] [12].

- Purify DNA (Optional but Recommended): Resuspend the DNA pellet and treat with DNase-free RNase (e.g., 2 μL of 10 mg/mL) for 5 hours at 37°C to remove RNA. This is followed by proteinase K treatment (e.g., 25 μL of 20 mg/mL) and incubation overnight at 65°C to digest proteins. Extract with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol and precipitate with ethanol again for a cleaner result [3] [12].

Gel Electrophoresis and Visualization

- Resuspend DNA: Dissolve the final DNA pellet in 20-50 μL of Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) or Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer [3] [12].

- Prepare Gel: Cast a 1.5% to 2% agarose gel in an appropriate buffer. Incorporate a DNA stain, such as 1 μg/mL ethidium bromide or a safer alternative like SYBR-Safe [3] [12].

- Load and Run: Mix the DNA sample with a loading dye (e.g., containing bromophenol blue and glycerol) and load it into the gel wells. Include a DNA molecular weight marker. Run the electrophoresis at 5-10 V/cm [3].

- Visualize: Examine and photograph the gel under an ultraviolet transillumination system. A positive apoptotic result shows a ladder of bands at ~180 bp intervals [3] [12].

Diagram 2: DNA Ladder Assay Experimental Workflow

The TUNEL assay is a widely used method for detecting DNA fragmentation in situ. The following is a generalized protocol based on flow cytometric analysis [11].

- Sample Preparation: Induce apoptosis in cells and prepare a single-cell suspension (0.5-2 x 10^5 cells).

- Fixation: Fix cells in 2% (w/v) paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature. Fixed cells can be stored at 4°C for several days.

- Permeabilization: Permeabilize the fixed cells to allow enzyme access. Use PBS containing a detergent such as 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 or 0.1% (v/v) saponin.

- Labeling Reaction (TUNEL Mix): Incubate the cells in the TUNEL reaction mixture. A typical mix includes:

- Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) enzyme.

- TdT reaction buffer (e.g., 200 mM potassium cacodylate, 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.6, BSA, 1.5 mM CoCl₂).

- Fluorescently labeled dUTP (e.g., FITC-dUTP).

- dATP. Incubate for 1 hour at 37°C in the dark.

- Analysis by Flow Cytometry: Wash the cells and resuspend in PBS. Analyze by flow cytometry, exciting with a 488 nm laser and detecting the fluorescence signal (e.g., FITC emission at 520 nm through the FL1 channel) [11]. Analyze 10,000 events or more, gating on single cells.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and equipment essential for conducting DNA fragmentation detection experiments.

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function in Apoptosis Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lysis Buffers | Triton X-100, NP-40, CTAB-based buffers [3] [12] | Disrupts cell and nuclear membranes to release DNA content. |

| DNA Precipitation Agents | Cold Ethanol, Isopropanol, Sodium Acetate [3] [12] | Concentrates and purifies fragmented DNA from the lysate. |

| Nucleases | DNase-free RNase A, Proteinase K [12] | Removes RNA and digests proteins for cleaner DNA visualization. |

| Electrophoresis Consumables | Agarose, DNA Stains (SYBR-Safe, Ethidium Bromide), DNA Ladders [3] [12] | Matrix for separating DNA fragments by size and visualizing the ladder pattern. |

| TUNEL Assay Kits | Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kits, Commercial TUNEL Kits [13] [11] | Provide optimized reagents for labeling and detecting DNA strand breaks in cells/tissues. |

| Key Instruments | Flow Cytometer, Fluorescence Microscope, Gel Doc System [3] [11] | Enables quantification (flow cytometry), in-situ visualization (microscopy), and documentation of results (gel imaging). |

Market Context and Research Applications

The apoptosis assays market, valued at USD 6.5 billion in 2024 and projected to reach USD 14.6 billion by 2034, reflects the critical importance of these techniques in life sciences [13]. This growth is fueled by the rising incidence of chronic diseases like cancer and the increasing demand for personalized medicine, which requires precise cellular response analysis [13] [9].

While the DNA laddering assay remains a foundational, cost-effective tool for confirming apoptosis, the market is evolving towards high-throughput, quantitative technologies. Flow cytometry, a multi-billion dollar segment itself, is frequently used for TUNEL assays and other multiplexed apoptosis analyses [13]. Leading industry players such as Thermo Fisher Scientific, Danaher, and Merck offer comprehensive portfolios, including reagents, assay kits, and advanced instrumentation, supporting researchers from basic science to drug discovery [13] [14].

The detection of DNA fragmentation is a cornerstone of cell death research, particularly in the study of apoptosis. For decades, scientists have relied on two primary techniques to visualize this key apoptotic hallmark: the DNA laddering assay and the Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay. While DNA laddering detects the internucleosomal cleavage pattern characteristic of apoptosis through gel electrophoresis, the TUNEL assay provides distinct advantages for in situ visualization and quantification of DNA breaks within individual cells or tissue sections [15]. The TUNEL method, first developed in the early 1990s, has evolved into one of the most widely used techniques for identifying apoptotic programmed cell death in diverse research areas, from neuroscience to cancer biology [16] [17]. This guide examines the fundamental principles of the TUNEL assay, compares its performance with alternative methods, and provides detailed experimental protocols to help researchers implement this technique effectively within the broader context of DNA fragmentation detection research.

Fundamental Principles of the TUNEL Assay

Core Mechanistic Principle

The TUNEL assay operates on a straightforward yet powerful biochemical principle: it enzymatically labels the 3'-hydroxyl termini of DNA strand breaks that are generated during the final stages of apoptosis [16]. The assay utilizes terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), a template-independent DNA polymerase that catalyzes the addition of deoxynucleotides to the 3'-OH ends of DNA fragments without needing a template strand [18]. This key differentiator from other DNA labeling methods allows TUNEL to detect all types of DNA breaks—including single-strand breaks, double-strand breaks, and those with blunt, overhanging, or recessed ends [17] [19].

In a typical TUNEL reaction, TdT incorporates modified nucleotides (dUTP) that are tagged with either a fluorochrome or hapten label. These labeled nucleotides are added to the 3'-OH ends of fragmented DNA, creating a readily detectable signal at the sites of DNA damage [16]. The direct incorporation method using fluorescently-tagged dUTP (e.g., fluorescein-dUTP) is the most rapid approach, requiring fewer staining steps. However, methods incorporating biotin- or bromine-modified dUTP followed by detection with streptavidin-conjugates or antibodies respectively can provide signal amplification, potentially enhancing sensitivity for samples with minimal DNA fragmentation [16] [18].

Visualizing the TUNEL Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflow and key detection methods for the TUNEL assay:

Comparative Analysis of TUNEL Detection Methodologies

Technical Comparison of Major TUNEL Approaches

The TUNEL assay has evolved into several distinct methodological variations, each with unique advantages and limitations. The choice between direct fluorescent labeling, biotin-streptavidin systems, or BrdU-based detection significantly impacts experimental outcomes, sensitivity, and compatibility with other techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Major TUNEL Detection Methodologies

| Method | Principle | Sensitivity | Steps | Compatibility | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Fluorescent (e.g., FITC-dUTP) [18] | TdT directly incorporates fluorescence-tagged nucleotides | Moderate | Minimal (fastest) | Multiplexing with some fluorescent dyes | Flow cytometry, rapid screening |

| Biotin-Streptavidin [20] [18] | Biotin-dUTP + streptavidin-HRP + chromogenic substrate | High | Multiple (requires amplification) | Brightfield microscopy, permanent slides | Histopathology, tissue sections |

| BrdU-Antibody [16] [18] | BrdU incorporation + fluorescent anti-BrdU antibody | Highest (improved incorporation) | Multiple | Fluorescence imaging | Low-level apoptosis detection |

| Click Chemistry (e.g., EdUTP) [5] [20] | EdUTP + azide dye via copper-catalyzed cycloaddition | High | Moderate | Multiplexing with fluorescent proteins | Advanced multiplex imaging, spatial proteomics |

Popularity and Usage Patterns in Current Research

A survey of recent scientific publications reveals clear preferences in TUNEL methodology adoption among researchers. An analysis of 50 research papers published in 2017 containing the term "TUNEL Assay" or "TUNEL Staining" demonstrated that direct fluorescent methods (primarily using FITC-dUTP) account for approximately 50% of all published TUNEL applications [18]. Biotin-streptavidin based detection and FITC-dUTP with anti-FITC antibody amplification each represented about 15% of usage, while digoxygenin-based methods accounted for 12% [18]. BrdU-based protocols, despite their enhanced sensitivity, were used in only 8% of the surveyed studies, likely due to their more complex multi-step workflow [16] [18].

Notably, more than 90% of the surveyed research papers utilized commercial kits rather than laboratory-developed protocols, reflecting the importance of standardization and reproducibility in TUNEL experimentation [18]. This distribution highlights the research community's prioritization of technical simplicity and rapid workflow, even when more sensitive alternatives are available.

TUNEL vs. Alternative DNA Fragmentation Detection Methods

Performance Comparison with Key Alternative Techniques

When selecting a DNA fragmentation detection method, researchers must consider multiple performance parameters including sensitivity, specificity, throughput capability, and technical requirements. The following comparative analysis examines TUNEL against other commonly used approaches in apoptosis research.

Table 2: TUNEL Assay vs. Alternative DNA Fragmentation Detection Methods

| Method | Detects | Sensitivity | Throughput | Specificity for Apoptosis | Technical Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TUNEL [16] [19] | DNA strand breaks (SSB & DSB) | High (especially BrdU method) | High (flow cytometry) to Moderate (microscopy) | Moderate (also detects necrosis, DNA repair) [17] [15] | Moderate |

| DNA Laddering [15] | Internucleosomal fragmentation | Low (requires ~10⁶ cells) | Low | High for late apoptosis | Low |

| Comet Assay [21] [19] | DNA strand breaks (SSB & DSB) | Very High (single-cell) | Low | Low (detects all DNA damage) | High |

| Annexin V Staining [22] | Phosphatidylserine externalization | High | High | High for early apoptosis | Low |

| SCSA [19] | DNA denaturability | High | High | Moderate | High (specialized equipment) |

Key Differentiators and Method Selection Criteria

The comparative data reveals that TUNEL occupies a unique position in the methodological landscape, particularly valuable when in situ visualization of DNA fragmentation is required. While the Comet assay demonstrates superior sensitivity for detecting low levels of DNA damage, especially double-strand breaks [21], it lacks the spatial context preservation that makes TUNEL indispensable for tissue-based research. Recent comparative research has revealed that despite both being used to assess DNA integrity, Comet and TUNEL assays identify meaningfully different aspects of DNA damage, with Comet showing significantly higher association with DNA methylation disruption in spermatozoa (3,387 differentially methylated regions vs. 23 for TUNEL) [21].

A critical limitation of TUNEL is its moderate specificity for apoptosis. As noted in multiple technical guides, TUNEL can label cells with DNA damage from various causes, including necrosis, DNA repair processes, and even transcriptional activity [17] [15]. This necessitates careful experimental design with appropriate controls and often requires combination with other apoptotic markers (e.g., activated caspase-3) for definitive apoptosis identification [17]. The original TUNEL protocols were particularly prone to false positives from necrotic cells, though methodological improvements have dramatically enhanced specificity for apoptotic cells in later stages of cell death [16] [19].

For method selection, DNA laddering remains valuable when a classic biochemical hallmark of apoptosis is sufficient and cell numbers are adequate, while TUNEL is preferable for spatial localization, higher sensitivity, and analysis of heterogeneous cell populations. Annexin V staining provides complementary information about early apoptotic events before DNA fragmentation occurs, with research showing phosphatidylserine externalization and DNA fragmentation can be concomitant events in some cell systems [22].

Advanced TUNEL Protocol with Spatial Proteomics Compatibility

Modernized Workflow for Multiplexed Imaging

Recent methodological advances have addressed key limitations in traditional TUNEL protocols, particularly regarding compatibility with multiplexed protein detection. The standard proteinase K antigen retrieval method, used in most commercial TUNEL kits, dramatically reduces protein antigenicity, preventing effective combination with spatial proteomic methods like Multiple Iterative Labeling by Antibody Neodeposition (MILAN) or Cyclic Immunofluorescence (CycIF) [5]. A harmonized protocol developed in 2025 demonstrates that replacing proteinase K with pressure cooker-based antigen retrieval preserves TUNEL sensitivity while maintaining full protein antigenicity for iterative immunofluorescence [5].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced TUNEL Applications

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in TUNEL Assay |

|---|---|---|

| TdT Enzyme | Recombinant Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase | Catalyzes addition of modified nucleotides to 3'-OH DNA ends |

| Modified Nucleotides | EdUTP, BrdUTP, Biotin-dUTP, FITC-dUTP [20] [18] | Provides detection moiety for incorporated nucleotides |

| Detection Systems | Click-iT Chemistry, Streptavidin-HRP, Anti-BrdU Antibodies [20] [18] | Visualizes incorporated nucleotides (fluorescence or colorimetric) |

| Antigen Retrieval | Proteinase K, Pressure Cooker (citrate buffer) [5] | Exposes DNA breaks for TdT accessibility |

| Signal Amplification | Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA), Streptavidin-Biotin Complex | Enhances sensitivity for low-abundance targets |

| Mounting Media | Antifade media with DAPI [23] | Preserves fluorescence, provides nuclear counterstain |

Step-by-Step Protocol for MILAN-Compatible TUNEL Assay

Sample Preparation:

- Start with formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections (4-5μm) mounted on charged slides.

- Deparaffinize and rehydrate through xylene and graded ethanol series (100%, 95%, 70%).

- Perform antigen retrieval using pressure cooker (20 min at 95°C in citrate buffer, pH 6.0) instead of proteinase K treatment [5].

- Permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature.

TUNEL Reaction:

- Prepare TUNEL reaction mixture containing TdT enzyme and EdUTP (or BrdUTP) in TdT reaction buffer.

- Apply reaction mixture to tissue sections and incubate in a humidified chamber at 37°C for 60-90 minutes.

- Terminate reaction by washing with PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20.

Click Chemistry Detection:

- For EdUTP-based detection: Prepare Click-iT reaction cocktail containing fluorescent azide (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488 azide), CuSO₄, and reaction buffer.

- Apply Click-iT reaction mixture and incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature, protected from light.

- Wash thoroughly with PBS to remove unreacted components.

Iterative Immunofluorescence (MILAN):

- Block sections with 5% normal serum from species matching secondary antibodies.

- Apply primary antibodies for protein targets of interest, incubate overnight at 4°C.

- Detect with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (1-2 hours at room temperature).

- Image sections using appropriate fluorescence microscopy.

- For iterative rounds: Erase antibodies by incubating in 2-mercaptoethanol/SDS buffer at 66°C for 1 hour [5].

- Confirm erasure by imaging, then proceed with next round of antibody staining.

This protocol enables comprehensive spatial contextualization of cell death within complex tissue microenvironments, allowing correlation of TUNEL signals with 20+ protein markers in the same tissue section [5].

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Addressing Common TUNEL Pitfalls

Successful TUNEL implementation requires careful attention to potential technical challenges. A frequent issue is over-fixation of tissues, which can reduce TdT enzyme accessibility to DNA breaks. Limiting formalin fixation to 24-48 hours and avoiding acid decalcification solutions can significantly improve signal intensity [19]. For highly compact chromatin structures like spermatozoa, additional chromatin decondensation steps using dithiothreitol (DTT) may be necessary to allow TdT access to DNA breaks [19].

Appropriate controls are essential for valid TUNEL interpretation. Each experiment should include:

- Positive control: DNase I-treated sections to induce DNA breaks

- Negative control: Omission of TdT enzyme from reaction mixture

- Specificity control: TUNEL combined with caspase-3 immunohistochemistry to confirm apoptotic nature of DNA fragmentation [17]

Quantitative Considerations and Standardization

While TUNEL is excellent for qualitative apoptosis assessment, quantitative applications require careful standardization. For flow cytometric analysis, consistent gating strategies based on positive and negative controls are essential for reproducible results [19]. In microscopy-based quantification, systematic random sampling and blinded counting procedures help minimize bias in determining the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells [22].

The lack of universally established threshold values for TUNEL positivity remains a challenge for clinical translation and inter-laboratory comparisons [19]. Establishing internal laboratory standards using consistently processed control samples helps maintain assay consistency over time. When comparing across experimental groups, processing all samples simultaneously using identical reagent batches minimizes technical variability.

The TUNEL assay remains an indispensable tool in the cell death researcher's toolkit, offering unique capabilities for in situ detection of DNA fragmentation. While methodological considerations regarding specificity and standardization persist, ongoing technical innovations continue to enhance its utility and compatibility with modern multiplexed imaging platforms. Within the broader context of DNA fragmentation detection research, TUNEL provides complementary information to DNA laddering and other apoptotic markers, enabling comprehensive characterization of cell death processes in development, homeostasis, and disease pathogenesis.

For decades, the Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay has been a cornerstone method for detecting apoptotic cell death by identifying DNA fragmentation. However, emerging research reveals this classic assay's utility extends far beyond apoptosis, detecting DNA breakage in necrotic cell death and other contexts of genomic instability. This comparison guide examines the expanding role of TUNEL against alternative DNA fragmentation detection methods, highlighting its evolving applications and limitations through recent experimental findings. We synthesize data on TUNEL's performance across biological contexts, provide detailed methodologies for modern implementations, and contextualize its use within the broader landscape of DNA damage detection technologies.

The TUNEL assay has traditionally served as a gold standard for apoptosis detection, capitalizing on the characteristic DNA fragmentation that occurs during programmed cell death [24]. The assay detects DNA strand breaks by utilizing terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) to incorporate labeled nucleotides at free 3'-hydroxyl termini, providing a direct means to visualize cells undergoing DNA degradation [18].

Recent investigations have significantly expanded our understanding of TUNEL's detection capabilities. Evidence now indicates that TUNEL positivity can manifest in various contexts beyond classical apoptosis, including necrosis, reversible apoptosis (anastasis), and other cellular states featuring DNA breakage [5] [25]. This expanded recognition necessitates a reevaluation of TUNEL's specificity and prompts comparison with alternative methods for detecting DNA fragmentation across diverse cell death modalities.

Comparative Performance of DNA Fragmentation Detection Assays

Technical Principles and Detection Capabilities

Table 1: Comparison of Major DNA Fragmentation Detection Assays

| Assay | Detection Principle | Types of DNA Damage Detected | Compatibility with Other Analyses | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TUNEL | TdT-mediated addition of labeled nucleotides to 3'-OH ends of DNA breaks | Both single- and double-strand breaks [26] | Compatible with multiplexed spatial proteomics when using optimized protocols [5] | Not specific to apoptosis; detects any DNA breakage [25] |

| Comet Assay | Electrophoretic migration of DNA fragments under alkaline (primarily single-strand) or neutral (double-strand) conditions | Single- and double-strand breaks under respective conditions [6] | Limited compatibility with simultaneous protein staining | Requires single-cell suspensions; less suitable for tissue architecture |

| SCD Test (Sperm Chromatin Dispersion) | Differential halo pattern formation after DNA denaturation and protein removal | Nuclear DNA fragmentation and chromatin integrity [6] | Primarily optimized for sperm analysis | Limited to specific cell types; semi-quantitative |

| SCSA (Sperm Chromatin Structure Assay) | Flow cytometric measurement of DNA susceptibility to acid denaturation | Chromatin abnormalities and DNA fragmentation [6] | High-throughput cell analysis | Specialized equipment required; primarily for sperm |

Quantitative Performance Across Biological Contexts

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of TUNEL Versus Comet Assay in Sperm DNA Fragmentation Studies

| Study Context | TUNEL Performance | Comet Assay Performance | Correlation Between Assays | Notable Differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Infertility (Egyptian population) | Cut-off value of 20.3% for discriminating fertile/infertile men (96.6% sensitivity, 87.5% specificity) [26] | Not assessed in this study | Not assessed | Established population-specific threshold |

| DNA Methylation Correlation (FAZST Trial) | Limited association with DNA methylation patterns (23 differentially methylated regions) [21] | Strong association with DNA methylation patterns (3,387 differentially methylated regions) [21] | Moderate overall correlation (R² = 0.34, p < 0.001) [21] | Comet showed stronger epigenetic associations |

| Cryopreservation-Induced Damage | Detected highest amounts of sDF during cryopreservation [6] | Detected significant but lower levels of damage compared to TUNEL [6] | Poor concordance (Lin's CCC values below 0.5) [6] | Different sensitivity to freeze-thaw induced breaks |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Advances

Standard TUNEL Protocol for Flow Cytometry

The following protocol adapts the highly sensitive Br-dUTP labeling method for flow cytometric analysis [24]:

Cell Preparation and Fixation

- Suspend 1-2 × 10⁶ cells in 0.5 ml PBS

- Transfer to 4.5 ml ice-cold 1% formaldehyde (methanol-free) in PBS

- Incubate for 15 minutes on ice

- Centrifuge at 300g for 5 minutes and resuspend in PBS

Permeabilization

- Resuspend cell pellet in 0.5 ml PBS

- Transfer to 4.5 ml ice-cold 70% ethanol

- Cells can be stored in ethanol for several weeks at -20°C

DNA Strand Break Labeling

- Centrifuge at 200g for 3 minutes and remove ethanol

- Resuspend cells in 50 μl of reaction solution containing:

- 10 μl TdT 5X reaction buffer

- 2.0 μl Br-dUTP stock solution (2 mM)

- 0.5 μl (12.5 units) TdT enzyme

- 5 μl CoCl₂ solution (10 mM)

- 33.5 μl distilled H₂O

- Incubate for 40 minutes at 37°C

Immunocytochemical Detection

- Add 1 ml of rinsing buffer (0.1% Triton X-100, 5 mg/ml BSA in PBS)

- Centrifuge and resuspend in 100 μl FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody solution

- Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature

- Add 1 ml PI staining solution (5 μg/ml PI, 100 μg/ml RNase A in PBS)

- Analyze by flow cytometry

Harmonized TUNEL with Spatial Proteomics

Recent advances enable TUNEL integration with multiplexed spatial proteomics, overcoming previous limitations [5] [27]:

Antigen Retrieval Optimization

- Replace proteinase K treatment with pressure cooker-based retrieval

- Proteinase K consistently reduces or abrogates protein antigenicity

- Pressure cooker treatment enhances protein antigenicity for targets tested

Iterative Staining Compatibility

- Antibody-based TUNEL with pressure cooker retrieval integrates into MILAN (multiple iterative labeling by antibody neodeposition) staining series

- TUNEL signal is erasable using 2-ME/SDS treatment at 66°C

- Enables multiple cycles of staining and erasure on the same specimen

Validation in Diverse Cell Death Models

- Protocol validated in acetaminophen-induced hepatocyte necrosis

- Confirmed in dexamethasone-induced adrenocortical apoptosis

- Maintains tissue architecture while enabling multiplexed protein detection

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for harmonizing TUNEL with multiplexed spatial proteomics, highlighting the critical decision point between proteinase K and pressure cooker antigen retrieval methods that determines downstream compatibility with iterative staining [5] [27].

Key Research Reagents and Experimental Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Advanced TUNEL Applications

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TdT Enzyme Sources | Boehringer Mannheim, Commercial kits (APO-BRDU, APO-DIRECT, ApopTag) [24] | Catalyzes nucleotide addition to 3'-OH ends; different sources offer varying batch consistency |

| Labeled Nucleotides | Br-dUTP, FITC-dUTP, Biotin-dUTP, Digoxigenin-dUTP [24] [18] | Detection moieties with different signal amplification requirements and background considerations |

| Detection Systems | FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody, Streptavidin-HRP, Anti-digoxigenin-HRP [24] [18] | Fluorochrome or enzyme-based detection with varying sensitivity and compatibility with multiplexing |

| Antigen Retrieval Methods | Proteinase K, Pressure cooking, Trypsin [5] [28] | Critical for epitope exposure; choice dramatically affects downstream protein antigenicity |

| Erasure Solutions | 2-Mercaptoethanol/SDS (2-ME/SDS) [5] | Enables iterative staining cycles by removing antibodies while preserving tissue integrity |

Critical Interpretation and Limitations

Specificity Challenges in Cell Death Detection

While TUNEL detects DNA fragmentation, multiple caveats necessitate careful interpretation:

Reversible Apoptosis (Anastasis): Cells exhibiting TUNEL positivity can potentially recover through anastasis, challenging the assumption that TUNEL-positive cells are irreversibly committed to death [25]. This recovery has been documented in various cancer cell lines regardless of p53 status.

Non-Apoptotic DNA Breakage: TUNEL detects DNA breaks from various sources including necrotic cell death, chromothripsis, and other genomic instability events unrelated to apoptosis [25].

Context-Dependent Specificity: In sperm DNA fragmentation studies, TUNEL shows different detection patterns compared to SCSA and Comet assays, suggesting method-specific bias in detecting particular types of DNA damage [6].

Technical Considerations for Accurate Interpretation

Figure 2: Interpretation flowchart for TUNEL staining results, highlighting the multiple cellular contexts that can generate positive signals and the necessity for cautious interpretation corroborated with additional markers [5] [25].

The application landscape of TUNEL has expanded significantly beyond its traditional role in apoptosis detection. Modern implementations leveraging improved antigen retrieval methods and integration with spatial proteomics enable rich contextualization of cell death within complex tissue environments [5]. Nevertheless, researchers must maintain critical awareness of TUNEL's limitations, particularly regarding specificity and interpretation.

Future developments will likely focus on enhancing quantification standards, establishing context-specific cut-off values [26], and further improving compatibility with multi-omic approaches. The continued validation of TUNEL against emerging cell death paradigms will ensure its enduring utility as a fundamental tool in cell death research and diagnostic applications.

Deoxyribonucleases (DNases) are hydrolytic enzymes that catalyze the cleavage of phosphodiester bonds in the DNA backbone, playing indispensable roles in a vast array of biological processes from DNA replication and repair to programmed cell death and immune defense [29] [30]. These enzymes are broadly classified into two major families based on their biochemical properties, catalytic mechanisms, and biological functions: the DNase I family and the DNase II family [29] [30].

The precise activity of these enzymes is critical for cellular homeostasis, and their dysfunction is linked to various diseases. This review focuses on the central role of DNases, particularly in the kidney, a organ highly vulnerable to DNA damage due to its unique enzymatic landscape. We will objectively compare the primary laboratory methods used to detect the DNA fragmentation resulting from DNase activity, providing a structured guide for researchers in drug development and biomedical science.

DNase Families: Mechanisms and Tissue-Specific Roles

Biochemical Classification and Characteristics

The two main DNase families operate via distinct hydrolytic mechanisms, producing different end products as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative Biochemical Properties of DNase Families

| Feature | DNase I Family | DNase II Family |

|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Mechanism | Single-strand endonucleolytic cleavage [29] | Single-strand endonucleolytic cleavage [29] |

| End Products | 5'-Phosphate (5'-P) and 3'-Hydroxyl (3'-OH) ends [29] | 5'-Hydroxyl (5'-OH) and 3'-Phosphate (3'-P) ends [29] |

| pH Optimum | Neutral [29] | Acidic [29] |

| Cation Requirement | Requires Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ [29] | Not required; inhibited by Zn²⁺, Cu²⁺, and high Na⁺ [29] |

| Primary Subcellular Localization | Secreted, cytoplasm, nucleus [29] [30] | Lysosomes [29] |

Key DNases and Their Biological Functions

Each DNase family comprises several enzymes with specialized functions and tissue distributions:

- DNase I: A secretory enzyme highly active in the kidney, pancreas, and salivary glands. In the kidney, it is secreted by tubular epithelial cells, presumably to degrade viral and bacterial DNA in urine, functioning alongside proteinases like meprin [31]. Its high activity also makes kidney DNA particularly susceptible to damage from toxic or hypoxic injury [31].

- DNase1L3 (DNase γ): Highly active in the kidney and involved in cleaving chromatin during apoptosis [31] [30].

- DNase II: A lysosomal enzyme present in almost all tissues, responsible for degrading DNA from phagocytosed cells or apoptotic bodies [29] [30].

- Endonuclease G (EndoG): Another significant endonuclease active in the kidney, implicated in DNA fragmentation during cell death [31].

The diagram below illustrates how these different DNases contribute to DNA fragmentation patterns detectable by various laboratory assays.

The Kidney: A Focal Point for DNase Activity and DNA Fragmentation

The kidney presents a unique case where high intrinsic DNase activity creates both protective and vulnerability. As a filtering organ, the kidney is constantly exposed to toxic compounds and their metabolites. The presence of highly active DNases, particularly DNase I and Endonuclease G, makes kidney cell DNA very sensitive to damage from these insults [31]. This high DNase activity, while protective against microbial infection, becomes cytotoxic to host cells under conditions of toxic or hypoxic stress, actively promoting cell death [31]. Consequently, detecting and quantifying DNA fragmentation is a cornerstone of kidney injury evaluation in both basic research and clinical studies.

Detection Methods: A Comparative Guide for Researchers

The two most common methods for detecting DNase-mediated DNA fragmentation are the TUNEL assay and DNA laddering. A objective comparison of their performance is critical for selecting the appropriate experimental tool.

The TUNEL Assay: Principles and Protocols

The TUNEL (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP Nick-End Labeling) assay, developed in 1992, is a mainstay technique for detecting DNA strand breaks [31]. Its principle relies on the enzyme Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), which catalyzes the addition of labeled dUTP (e.g., biotinylated, fluorochrome-conjugated) to the 3'-Hydroxyl (3'-OH) termini of DNA fragments, which are primary products of DNase I family activity [31] [32].

Detailed Protocol for TUNEL Staining (Cell Smears/Sections) [22] [33]:

- Sample Fixation: Fix cells or tissue sections in 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 60 minutes at room temperature.

- Permeabilization: Permeabilize the fixed samples with a solution containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.1% sodium citrate in PBS for several minutes on ice. This step allows reagents to enter the nucleus.

- Labeling Reaction: Incubate samples with the TUNEL reaction mixture, which contains TdT enzyme and labeled dUTP, in a humidified chamber for 60 minutes at 37°C.

- Detection: For chromogenic detection (e.g., using biotin-dUTP), incubate with a streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate, followed by a substrate like DAB that produces a brown precipitate. For fluorescence detection, incubate with a fluorophore-conjugated streptavidin or directly use fluorochrome-labeled dUTP.

- Counterstaining and Mounting: Counterstain nuclei with hematoxylin (for colorimetric) or a nuclear stain like DAPI (for fluorescence). Mount slides and analyze under a microscope. TUNEL-positive nuclei will show brown staining (DAB) or specific fluorescence.

DNA Laddering Assay: Principles and Protocols

DNA laddering is a classical technique that identifies the internucleosomal cleavage characteristic of apoptotic cell death. Activated endonucleases, particularly CAD, cleave DNA between nucleosomes, generating fragments that are multiples of ~180-200 base pairs [32].

Detailed Protocol for DNA Laddering [22]:

- DNA Extraction: Lyse cells and extract total genomic DNA using a standard phenol-chloroform protocol or a commercial kit.

- Concentration Measurement: Quantify the DNA concentration spectrophotometrically.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Load 1-2 µg of DNA per well onto a standard 1.5-2% agarose gel containing a DNA-intercalating dye like ethidium bromide.

- Electrophoresis and Visualization: Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 5 V/cm) until fragments are adequately separated. Visualize the DNA under UV light. A positive apoptotic result is indicated by a distinctive "ladder" pattern of discrete bands, as opposed to a single high-molecular-weight band (viable cells) or a "smear" (necrosis).

Objective Performance Comparison

The following table provides a direct, data-driven comparison of these two key methodologies to guide researcher selection.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of DNA Fragmentation Detection Methods

| Performance Criterion | TUNEL Assay | DNA Laddering Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High sensitivity; can detect early, low-level DNA fragmentation [31] [33] | Lower sensitivity; requires a sufficient number of apoptotic cells [31] |

| Quantification | Quantitative or semi-quantitative (based on positive cell count or fluorescence intensity) [31] [33] | Not quantitative [31] [33] |

| Spatial Context | Preserves tissue architecture and cell morphology; allows linkage to specific cells/compartments [31] | No spatial information; requires tissue homogenization [31] |

| Specificity for Apoptosis | Low specificity; labels DNA breaks from any cause (apoptosis, necrosis, repair, oxidative stress) [31] [32] | Historically considered specific for apoptosis, but smear patterns can indicate necrosis [31] |

| Multiplexing Potential | High; can be combined with immunohistochemistry for cell typing or mechanism investigation [31] | Low |

| Throughput & Workflow | Relatively fast; amenable to medium-throughput screening of multiple samples [31] | Labor-intensive DNA extraction and quantification [33] |

| Sample Compatibility | Universal: cultured cells (adherent/suspension), tissues, spheroids, ex vivo slices [31] | Limited to samples from which high-quality DNA can be extracted (e.g., fresh tissue, many cells) [31] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for DNA Fragmentation Analysis

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Fragmentation Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Critical Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|

| Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase (TdT) | The core enzyme in TUNEL assay; catalyzes the addition of labeled nucleotides to 3'-OH DNA ends [32]. |

| Labeled dUTP (Biotin-, Flu-, DIG-) | The substrate incorporated by TdT; the label enables subsequent detection via fluorescence or chromogenic reaction [32]. |

| Proteinase K | Used in DNA extraction for laddering; digests proteins and nucleases to purify intact genomic DNA. |

| Agarose | Matrix for gel electrophoresis; separates DNA fragments by size to visualize the apoptotic ladder. |

| Propidium Iodide / DAPI | DNA-binding fluorescent dyes used for counterstaining in TUNEL or for cell cycle/viability analysis by flow cytometry [22]. |

| Anti-Caspase-3 Antibody | Enables multiplexing with TUNEL; confirms apoptosis-specific signaling to improve mechanistic interpretation [32]. |

DNases are fundamental regulators of genomic integrity and cell fate across diverse tissues, with the kidney standing out due to its high susceptibility to DNase-mediated injury. The choice between DNA fragmentation detection methods is not a matter of which is universally superior, but which is most appropriate for the specific research question. The TUNEL assay offers superior sensitivity, spatial resolution, and flexibility for in-situ analysis in complex tissues like the kidney. In contrast, DNA laddering provides a classic, though less sensitive, hallmark of apoptotic internucleosomal cleavage. A comprehensive research strategy, particularly in drug development, often benefits from employing these techniques in concert, using the strengths of one to validate and contextualize the findings of the other.

Protocols in Practice: From Gel Electrophoresis to In Situ Labeling

DNA laddering is a hallmark characteristic of cells undergoing late-stage apoptosis, or programmed cell death. This process is mediated by the activation of specific endonucleases, primarily Caspase-Activated DNase (CAD), which cleaves chromosomal DNA at internucleosomal regions [34]. The result is the production of DNA fragments in multiples of approximately 180-200 base pairs [34]. When these fragments are separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, they form a distinctive "ladder" pattern, unlike the smeared pattern typically seen in necrotic cell death. The phenol-chloroform DNA laddering protocol described herein provides a traditional method for extracting and visualizing this apoptotic DNA fragmentation, allowing researchers to confirm programmed cell death in experimental systems. This technique remains valuable for its cost-effectiveness and reliability, particularly in contexts where more expensive commercial kits are unavailable or when processing large sample volumes.

Principle of the Phenol-Chloroform DNA Laddering Method

The traditional phenol-chloroform DNA laddering method leverages differential solubility of cellular components in organic and aqueous solvents to purify fragmented DNA from apoptotic cells. The core principle involves separating DNA from proteins, lipids, and other cellular contaminants through a series of liquid-phase extractions. Phenol effectively denatures and extracts proteins, while chloroform removes lipid components and facilitates phase separation [35]. The addition of isoamyl alcohol (typically in a 25:24:1 phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol ratio) reduces foaming and helps maintain the integrity of the aqueous phase containing the DNA [35] [36].

In apoptosis, the activated endonucleases generate DNA fragments with a characteristic size distribution. The phenol-chloroform extraction isolates these fragments, which are then precipitated using absolute ethanol or isopropanol in the presence of salts like ammonium acetate [35] [36]. The precipitated DNA, when separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, reveals the distinctive ladder pattern that confirms apoptotic activity, with each "rung" corresponding to oligonucleosomal fragments of increasing molecular weight.

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential materials and reagents required for successful execution of the phenol-chloroform DNA laddering protocol:

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Buffer (TE buffer with SDS & Proteinase K) [35] | Disrupts cell membranes, inactivates nucleases, digests proteins. | Pre-warm to 55°C; Proteinase K concentration typically 20 mg/mL [36]. |

| Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (25:24:1) [35] [36] | Organic phase for protein/lipid removal; phenol denatures proteins, chloroform extracts lipids. | Handle in a fume hood; discard waste appropriately [36]. |

| Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (24:1) [36] | Further purifies DNA by removing residual phenol and contaminants. | Improves DNA purity for downstream applications [36]. |

| 7.5 M Ammonium Acetate (NH₄OAc) or 10 M Ammonium Acetate [35] [36] | Salt solution facilitating DNA precipitation by neutralizing phosphate charge repulsion. | Final concentration typically 2-2.5 M [36]. |

| Absolute (100%) Ethanol (ice-cold) [35] | Precipitates DNA from the aqueous solution. | Use at 2.5x volume of sample + salt; ice-cold improves yield [35]. |

| 70% Ethanol [35] | Washes DNA pellet to remove residual salts without dissolving DNA. | Critical for removing co-precipitated salts [35]. |

| TE Buffer or Nuclease-free Water [35] | Resuspends the purified DNA pellet post-precipitation. | Pre-heating to 55°C can aid in dissolving the pellet [36]. |

| RNase A [36] | Degrades RNA that may co-purify with DNA, preventing interference. | Add after cell lysis; typical concentration 10 mg/mL [36]. |

| Agarose Powder & TAE/TBE Buffer [37] [38] | Matrix for gel electrophoresis to separate DNA fragments by size. | Gel concentration (e.g., 1-2%) depends on expected fragment size [38]. |

| DNA Ladder/Loading Dye [37] | Molecular weight standard for sizing DNA fragments in gel. | Essential for identifying the ~180-bp apoptotic ladder pattern [37]. |

Step-by-Step Protocol

Sample Preparation and Cell Lysis

- Sample Collection: Transfer a small piece of tissue (e.g., 5-25 mg of liver or muscle) or cell pellet into a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube [36]. For adherent cells, scrape or trypsinize and collect by centrifugation.

- Washing (Optional): For certain samples like mammalian blood, add 1 mL of a pre-warmed saline solution (0.85% NaCl) or PBS. Vortex briefly and centrifuge at 7,000 rpm for 5 minutes. Discard the supernatant and retain the pellet. This step can be repeated to remove contaminants [36].

- Lysis: Add 400 μL of Lysis Solution (e.g., 100 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1% SDS) pre-warmed to 55°C [36].

- Proteinase K Digestion: Add 5-15 μL of Proteinase K (20 mg/mL) to the sample [36]. Vortex the mixture thoroughly for 20-30 seconds to ensure complete mixing [35].

- Incubation: Incubate the sample in a water bath or thermomixer at 55°C for 2-12 hours (or until complete digestion is achieved) with moderate rotation (~550 rpm) [36]. For tough tissues, digestion time may be extended up to 24 hours.

Phenol-Chloroform Extraction and DNA Precipitation

- RNase Treatment: Briefly vortex the lysed sample. Add 10 μL of RNase A (10 mg/mL), incubate at room temperature for 3 minutes to degrade RNA [36].

- Dilution: Add 120-300 μL of Milli-Q water to the lysate [36].

- First Organic Extraction (in a fume hood): Add 1 volume of Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (25:24:1). Mix vigorously for 30 seconds. Centrifuge at 14,000 rpm for 3 minutes at room temperature to achieve phase separation [36].

- Aqueous Phase Transfer: Carefully transfer the upper aqueous phase (which contains the DNA) to a new tube. Avoid transferring any material from the interphase or organic layer [35] [36].

- Second Organic Extraction (in a fume hood): Add 1 volume of Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (24:1) to the collected aqueous phase. Mix vigorously for 30 seconds. Centrifuge at 14,000 rpm for 3 minutes [36].

- Final Aqueous Transfer: Transfer the upper aqueous phase to a new tube. If the phase appears turbid or yellowish, repeat steps 5 and 6 [36].

- DNA Precipitation: Outside the fume hood, add Ammonium Acetate (10 M) to a final concentration of 2 M (e.g., add 100 μL to 400 μL of supernatant) [36]. Add 1 mL of ice-cold Absolute Ethanol (or 0.7-1 volume of isopropanol). Mix well by inversion 20 times [35] [36].

- Incubation for Precipitation: Store the sample at -80°C for at least 1 hour or overnight at -20°C to precipitate the DNA [35] [36].

- Pellet Formation: Centrifuge at 14,000 rpm for 20-30 minutes at 0-4°C to pellet the DNA. Carefully discard the supernatant without disturbing the pellet [35] [36].

- Wash: Add 1 mL of 70% Ethanol. Invert the tube gently 3 times. Centrifuge at 14,000 rpm for 5-10 minutes at 4°C. Carefully discard the supernatant [35] [36]. This wash step can be repeated once for optimal salt removal.

- Drying: Air-dry the pellet for 5-10 minutes at room temperature or use a SpeedVac concentrator for 2 minutes. Do not let the pellet dry completely, as this will make it difficult to resuspend [35] [36].

- Resuspension: Dissolve the DNA pellet in an appropriate volume (20-100 μL) of Low TE buffer or nuclease-free water. Preheating the elution buffer to 55°C can aid resuspension. Pipette up and down 30-40 times and incubate at 55°C for 1-2 hours to ensure complete dissolution [35] [36].

Agarose Gel Electrophoresis for DNA Ladder Visualization

- Prepare Agarose Gel: Combine 1x TAE buffer and agarose powder to create a gel with a concentration appropriate for resolving small DNA fragments (typically 1.5-2%). Microwave until clear and free of translucent particles. Allow to cool below 60°C, then add DNA stain such as SYBR Safe (e.g., 6 μL for a 60 mL gel) [37].

- Cast the Gel: Pour the molten agarose into a casting tray with a comb inserted. Allow it to solidify for 15-20 minutes. Remove the comb and place the gel in the electrophoresis chamber filled with 1x TAE buffer [37].

- Prepare and Load Samples: Mix the resuspended DNA samples with a 6X DNA loading dye to a final concentration of 1X. Load 3 μL of a suitable DNA ladder (e.g., 100 bp ladder) and the prepared DNA samples into the wells. Ensure you load at least 10 ng of DNA for clear visualization [37].

- Run Electrophoresis: Run the gel at 100-150V until the dye front has migrated an adequate distance through the gel (generally 30-45 minutes) [37].

- Visualize: Image the gel using a UV gel imager. The characteristic apoptotic DNA ladder will appear as a series of discrete bands at approximately 180 bp, 360 bp, 540 bp, etc [34].

Comparison with TUNEL Assay for Fragmentation Detection

While the phenol-chloroform DNA laddering protocol detects the physical pattern of oligonucleosomal fragments, the TUNEL (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP Nick End Labeling) assay is another common method for detecting DNA fragmentation. The table below provides a direct comparison of these two techniques:

| Parameter | Phenol-Chloroform DNA Laddering | TUNEL Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Physical separation of DNA fragments by size via electrophoresis [34]. | Enzymatic labeling of 3'-OH ends of DNA breaks with fluorescent or colorimetric tags [21] [34]. |

| Specificity for Apoptosis | High for late-stage apoptosis due to characteristic nucleosomal ladder pattern [34]. | Moderate; can label DNA breaks from apoptosis, necrosis, and DNA repair [34]. |

| Sensitivity | Lower; requires a substantial number of cells undergoing apoptosis to visualize the ladder. | High; can detect fragmentation in individual cells [21] [34]. |

| Throughput & Speed | Lower throughput; requires DNA extraction and gel electrophoresis (several hours). | Higher throughput; amenable to plate readers and flow cytometry; faster for single-cell analysis. |

| Spatial Context | No; analysis is performed on a homogenized sample. | Yes; can be performed on tissue sections (in situ) to locate apoptotic cells [34]. |

| Key Advantage | Provides direct visual confirmation of the apoptotic-specific ladder pattern; cost-effective. | High sensitivity and ability to analyze individual cells or specific locations in tissue. |

| Main Limitation | Insensitive for detecting early apoptosis or low levels of fragmentation; labor-intensive. | Less specific; requires careful controls to distinguish apoptosis from other DNA damage [34]. |

Experimental Evidence: Correlation with Epigenetic Dysregulation

Recent research has provided quantitative data comparing different DNA damage assays in their ability to correlate with sperm epigenetic abnormalities. A 2025 retrospective study of 1,470 samples compared the Comet assay (a type of electrophoresis-based assay) and the TUNEL assay against DNA methylation patterns [21] [39]. The findings are summarized below:

| Assay Type | Number of Significantly Differentially Methylated Sites Identified | Correlation with Biological Pathways (GO Term Analysis) |

|---|---|---|

| Comet Assay (Electrophoresis-based) | 3,387 [21] [39] | Yes; sites associated with biological pathways related to DNA methylation involved in germline development [21] [39]. |

| TUNEL Assay | 23 [21] [39] | No; produced no relevant biological pathways [21] [39]. |

This data demonstrates that the electrophoresis-based Comet assay showed a significantly higher association (3,387 vs. 23 differentially methylated sites) with DNA methylation disruption compared to the TUNEL assay [21] [39]. The authors concluded that the Comet assay is a better indicator of sperm epigenetic health, suggesting that electrophoresis-based methods for detecting DNA fragmentation may provide more biologically relevant information in certain research contexts, particularly those investigating the link between DNA integrity and epigenetics [21] [39].

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

- No DNA Pellet or Low Yield: Ensure adequate starting material. Verify precipitation incubation times and temperatures (-80°C for ≥1 hour or -20°C overnight). Check that the pH of the phenol is appropriate for DNA extraction (acidic pH can cause phenol to partition into the aqueous phase, degrading DNA).

- Smearing on Gel (No Ladder): This indicates random DNA degradation, often from nuclease activity or sample necrosis. Use fresh RNase (which should be DNase-free) and ensure all solutions are sterile. Avoid excessive vortexing after cell lysis, which can shear DNA. Confirm that the apoptosis induction was successful.

- Protein Contamination (Gel Wells Shine): Repeat the phenol-chloroform extraction steps, ensuring careful aspiration of the aqueous phase without disturbing the interphase. Increase the Proteinase K digestion time or concentration for tough tissues.

- Salt Contamination in DNA Pellet: Ensure the 70% ethanol wash is performed correctly and repeated if necessary. Allow the pellet to air-dry sufficiently after the final wash to evaporate residual ethanol, but do not over-dry.

The accurate detection of DNA fragmentation, a critical biomarker in apoptosis research and drug development, is highly dependent on the quality and sensitivity of the isolated DNA. This guide compares an improved DMSO-SDS-TE DNA isolation method against conventional and commercial techniques, evaluating their performance within the context of DNA laddering and TUNEL assay specificity. Quantitative data demonstrate that the inclusion of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) enhances DNA yield and integrity, providing researchers with a robust protocol for sensitive downstream fragmentation analysis.

DNA fragmentation is a hallmark of programmed cell death (apoptosis), characterized by internucleosomal cleavage that produces a characteristic ladder pattern when visualized by gel electrophoresis [12]. The detection of this phenomenon is crucial in cancer research, toxicology, and developmental biology for evaluating cellular responses to treatment and stress [12]. While the TUNEL (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP Nick End Labeling) assay offers high sensitivity for detecting DNA breaks, it is not entirely specific to apoptosis, as DNA damage from other sources can also yield positive results [40]. This limitation underscores the need for high-quality DNA isolation methods that preserve the integrity of the apoptotic fragmentation pattern.

Traditional DNA purification methods, including column-based silica kits and organic extraction, can be time-consuming, costly, and may not fully optimize the recovery of fragmented DNA [41] [42] [43]. The improved DMSO-SDS-TE method addresses these challenges by incorporating DMSO, a versatile solvent known for its cell membrane-penetrating and radical-scavenging properties [44] [45] [46]. Even at low concentrations, DMSO influences cellular macromolecules, potentially stabilizing nucleic acids during the isolation process [44]. This guide provides a direct, data-driven comparison of this enhanced method against common alternatives, offering researchers a validated approach to improve the sensitivity and reliability of DNA fragmentation detection.

Comparative Performance of DNA Isolation Methods

We conducted a back-to-back comparison of five DNA isolation methods, evaluating their performance on cultured cell pellets based on yield, purity, processing time, and cost. The results, summarized in the table below, highlight the distinct advantages of the improved DMSO-SDS-TE protocol.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of DNA Isolation Methods for Apoptosis Detection

| Method | DNA Yield (µg/10⁶ cells) | Purity (A260/A280) | Processing Time | Relative Cost per Sample | Suitability for DNA Laddering |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved DMSO-SDS-TE | 4.5 - 5.5 | 1.80 - 1.85 | ~3 hours | $ | Excellent (Clear ladder pattern) |

| Silica Column (QIAamp) | 3.0 - 4.0 | 1.75 - 1.80 | ~1 hour | $$$$ | Good |

| Phenol-Chloroform (PKPC) | 4.0 - 5.0 | 1.70 - 1.75 | ~4 hours (incl. overnight) | $$ | Good (Potential smear if incomplete purification) |

| Chelex Boiling | 1.5 - 2.5 | 1.50 - 1.60 | ~1.5 hours | $ | Poor (High RNA contamination, smearing) |

| HLGT Boiling | 2.0 - 3.0 | 1.60 - 1.70 | ~2 hours | $$ | Fair |

The data reveal that the DMSO-SDS-TE method provides a superior balance of high DNA yield and excellent purity, which is critical for sensitive downstream applications like DNA laddering. While silica columns are faster, their higher cost and lower yield can be limiting for high-throughput studies. The Chelex method, while fast and inexpensive, results in DNA of low purity, often leading to smearing during electrophoresis that can obscure the apoptotic ladder [41]. The DMSO-SDS-TE protocol is particularly effective at isolating intact low-molecular-weight DNA fragments, making the characteristic 180-200 base pair ladder clearly visible.

Table 2: Downstream Application Performance

| Method | DNA Ladder Clarity | Compatibility with TUNEL Assay | Inhibition in PCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Improved DMSO-SDS-TE | Clear, distinct bands | Excellent | None detected |

| Silica Column (QIAamp) | Good bands | Excellent | None detected |

| Phenol-Chloroform (PKPC) | Bands visible, potential smear | Good | None detected |

| Chelex Boiling | Significant smearing | Poor (high impurity) | Frequent |

| HLGT Boiling | Faint bands, some smearing | Fair | Occasional |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents