Hoechst and DAPI in Fluorescence Microscopy: A Comprehensive Guide to Chromatin Condensation Analysis

This article provides a thorough exploration of Hoechst and DAPI fluorescent dyes as powerful tools for investigating chromatin condensation and nuclear architecture.

Hoechst and DAPI in Fluorescence Microscopy: A Comprehensive Guide to Chromatin Condensation Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a thorough exploration of Hoechst and DAPI fluorescent dyes as powerful tools for investigating chromatin condensation and nuclear architecture. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational principles, advanced methodologies, and practical protocols for applications ranging from basic DNA staining to super-resolution microscopy and quantitative chromatin analysis. We address critical troubleshooting aspects, including photoconversion artifacts and staining optimization, while offering a definitive comparative analysis to guide dye selection for specific experimental needs in cell biology, cytogenetics, and biomedical research.

The Science of DNA Binding: How Hoechst and DAPI Illuminate Chromatin Structure

Sequence-specific recognition of DNA is fundamental to controlling gene expression, enabling bioimaging, and developing diagnostic and therapeutic strategies [1]. Among the various modes of DNA interaction, minor groove binding presents a highly specific molecular recognition pathway, particularly for AT-rich sequences [1]. The minor groove of B-DNA, with its unique landscape of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors at the edges of nucleobases, provides an ideal interface for small molecule recognition [1]. Molecules exhibiting 'isohelicity'—a molecular curvature complementary to the DNA minor groove concavity—demonstrate enhanced binding affinity and selectivity [1].

Fluorescence-based techniques have revolutionized the study of these interactions, allowing real-time monitoring of DNA conformational changes and structural reorganization in living cells [1] [2]. This application note details the molecular mechanisms of minor groove binding to AT-rich DNA sequences, provides quantitative comparisons of key DNA-binding dyes, outlines detailed protocols for advanced fluorescence applications, and visualizes key experimental workflows and mechanisms.

Molecular Probes for AT-Rich Sequence Recognition

Several small molecule dyes exhibit preferential binding to the minor groove of AT-rich DNA sequences, each with distinct photophysical properties and binding characteristics. Table 1 summarizes the key features of the most commonly used probes.

Table 1: Key Fluorescent Probes for AT-Rich DNA Minor Groove Binding

| Probe Name | Binding Mode & Specificity | Excitation/Emission Maxima (nm) | Key Applications | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hoechst 33342 | Minor groove binder; prefers 5'-AAA/TTT-3' [3] [4] | ~350/~461 [3] [4] | Live-cell nuclear staining, cell cycle analysis, stem cell side population analysis [3] [4] | High cell permeability, low cytotoxicity (live-cell preferred) [3] [5] | Mutagenic potential, UV excitation required [3] [4] |

| Hoechst 33258 | Minor groove binder; prefers 5'-AAA/TTT-3' [3] [4] | ~350/~461 [3] [4] | Nuclear staining (fixed & live cells), DNA quantification [3] [4] [5] | High affinity (Kd 1-10 nM) [3]; more water-soluble than Hoechst 33342 [5] | Less cell-permeable than Hoechst 33342 [3] [5] |

| DAPI | Minor groove binder (AT-rich); can intercalate at GC sites at high concentrations [2] | 358/461 [5] | Fixed cell nuclear staining, chromosome staining [2] [5] | High quantum yield when bound to DNA (φf = 0.92) [2]; stable in dilute solutions [5] | Less cell-permeable, more toxic than Hoechst (fixed-cell preferred) [5] |

| QCy-DT | Sequence-specific minor groove binder for 5'-AAATTT-3' [1] | Near-Infrared (NIR) [1] | Selective staining of AT-rich genomes (e.g., Plasmodium falciparum), live-cell imaging [1] | NIR emission, large Stokes shift, low toxicity, photostable [1] | Novel probe, less established protocol [1] |

| Netropsin | Minor groove binder; very high AT-rich specificity [6] | Non-fluorescent [6] | Competitive binding assays for DNA mapping [6] | Exceptional sequence specificity [6] | Non-fluorescent, used as competitor [6] |

| SiR-Hoechst | Minor groove binder (Hoechst conjugate) [3] | Far-red emission (~670 nm) [3] | Live-cell imaging, STED super-resolution microscopy [3] | Far-red excitation/emission, fluorogenic (50-fold turn-on), low cytotoxicity [3] | Reduced binding affinity vs. parent Hoechst [3] |

The strong preference for AT-rich sequences exhibited by Hoechst dyes and DAPI stems from their molecular structure, which fits precisely into the narrow minor groove of B-DNA, forming hydrogen bonds with adenine and thymine bases [3] [4]. Upon binding, these dyes typically exhibit a significant fluorescence enhancement—up to 30-fold for Hoechst dyes—due to suppression of rotational relaxation and reduced hydration [3].

Table 2: Quantitative Fluorescence Lifetime Responses to Chromatin Condensation Changes

| Experimental Condition | Probe Used | Effect on Chromatin Compaction | Measured Fluorescence Lifetime Change | Biological Interpretation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertonic Medium | Hoechst 34580 | Induced compaction | ↓ ~2% decrease | Increased molecular crowding shortens lifetime [7] | [7] |

| Valproic Acid (HDAC inhibitor) | Hoechst 34580 | Induced decompaction | ↑ ~1% increase | Chromatin decompaction prolongs lifetime [7] | [7] |

| X-ray Irradiation | Hoechst 34580 | Induced decompaction | ↑ Pan-nuclear increase | Radiation-induced chromatin decondensation [7] | [7] |

| Constitutive Heterochromatin (vs. Euchromatin) | DAPI | Naturally more compact | ↓ Shorter lifetime (e.g., τ9b = 2.21 ± 0.05 ns vs τbulk = 2.80 ± 0.09 ns) | Compact heterochromatin exhibits distinct molecular environment [2] | [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Minor Groove Binding Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Permeable Minor Groove Binders | Live-cell nuclear staining and dynamics | Hoechst 33342 (≤1 µg/mL) for viable cells; SiR-Hoechst for far-red/far-red and super-resolution imaging [3] [5] |

| High-Affinity Minor Groove Binders | Fixed-cell staining, high-resolution structural studies | Hoechst 33258 (Kd 1-10 nM for specific binding); DAPI in mounting medium for fixed samples [3] [5] |

| Sequence-Specific Competitive Binders | DNA mapping, binding site competition studies | Netropsin for competitive displacement of fluorescent dyes in AT-rich regions [6] |

| NIR / Far-Red Probes | Deep tissue imaging, multicolor applications, reduced phototoxicity | QCy-DT for NIR imaging of AT-rich parasites; SiR-Hoechst for live-cell STED microscopy [1] [3] |

| FLIM-Compatible Probes | Chromatin compaction assessment, microenvironment sensing | Hoechst 34580, Syto13; lifetime changes reflect chromatin state independent of probe concentration [8] [7] |

| Oxygen Scavenging Systems | Photostability for single-molecule localization microscopy | Glucose oxidase/catalase in glycerol to optimize blinking behavior for SMLM [9] |

| Photoconversion-Compatible Mounting Media | Reducing dye photoconversion artifacts | Hard-set mounting media (e.g., EverBrite Hardset) instead of glycerol-based media [5] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Staining Live Cells with Hoechst Dyes or DAPI

Principle: Cell-permeable fluorescent dyes bind stoichiometrically to DNA in the minor groove, enabling nuclear visualization and quantification [3] [5].

Materials:

- Hoechst 33342 (for live cells) or DAPI (for fixed cells) stock solution (e.g., 10 mg/mL in water) [5]

- Complete cell culture medium

- Appropriate cell lines

Procedure:

- Dye Solution Preparation: Add Hoechst 33342 to complete culture medium to a final concentration of 1 µg/mL. For DAPI live-cell staining, use 10 µg/mL [5].

- Medium Exchange: Remove culture medium from cells and replace with dye-containing medium.

- Incubation: Incubate cells at room temperature or 37°C for 5-15 minutes.

- Imaging: Image cells without washing. Nuclear staining remains stable after washing if desired.

- Alternative Direct Addition Method: For minimal disturbance, prepare a 10X dye solution in medium and add directly to cells (1:10 volume ratio), mixing immediately by gentle pipetting [5].

Notes:

- Hoechst 33342 is generally preferred for live cells due to better permeability and lower toxicity [5].

- For fixed cells, DAPI at 1 µg/mL is recommended [5].

- Protect stained samples from light to minimize photobleaching and photoconversion [5].

Protocol: Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) for Chromatin Compaction

Principle: Fluorescence lifetime of DNA-bound dyes is sensitive to local microenvironment changes, providing a quantitative measure of chromatin compaction independent of dye concentration [2] [7].

Materials:

- Hoechst 34580 or Syto13 dyes

- FLIM-capable microscope system with time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC)

- Control compounds for chromatin modulation (e.g., Valproic acid for decompaction, hypertonic medium for compaction)

Procedure:

- Cell Staining: Stain living cells with Hoechst 34580 according to standard protocols.

- Control Preparation:

- FLIM Acquisition:

- Use two-photon or UV laser excitation appropriate for the dye.

- Collect photons using TCSPC electronics.

- Adjust laser power and acquisition time to obtain sufficient photons for fitting while avoiding pile-up effects and counting loss [7].

- For each condition, acquire data from multiple cells.

- Data Analysis:

- Fit fluorescence decay curves to multi-exponential models.

- Calculate amplitude-weighted average lifetime.

- Generate lifetime maps and histograms for comparison.

- Apply pile-up and counting loss corrections if necessary, especially at moderate count rates in inhomogeneous samples [7].

Notes:

- Hoechst 34580 shows ~1% lifetime increase with VPA-induced decompaction and ~2% decrease with hyperosmolar compaction [7].

- The difference between heterochromatin and euchromatin lifetime is reduced after treatments [7].

- FLIM data should be optimized using pile-up and counting loss correction for accurate readouts [7].

Protocol: Competitive Binding Assay for DNA Sequence Mapping

Principle: Non-fluorescent sequence-specific ligands (e.g., netropsin) displace fluorescent dyes from preferred binding sites, creating a fluorescence barcode reflecting underlying AT/GC content [6].

Materials:

- YOYO-1 or similar DNA intercalating dye

- Netropsin (AT-specific minor groove binder)

- Nanofluidic channels for DNA stretching

- TBE buffer with β-mercaptoethanol (3% v/v) to suppress photodamage

Procedure:

- DNA Staining: Incubate long DNA molecules (e.g., bacteriophage DNA) with YOYO-1 at a base pair:dye ratio of ~5:1 [6].

- Competitor Addition: Add netropsin at varying molar excess ratios relative to YOYO-1 (e.g., 100:1 to 500:1) [6].

- DNA Linearization: Introduce DNA mixture into nanofluidic channels for spontaneous stretching.

- Imaging: Acquire fluorescence images of stretched DNA molecules using standard epifluorescence microscopy.

- Barcode Analysis: Analyze fluorescence intensity profiles along DNA molecules. AT-rich regions appear darker due to netropsin displacement of YOYO-1 [6].

Notes:

- This single-step assay produces reproducible barcodes without requirement for temperature control or denaturants [6].

- Optimal netropsin:YOYO-1 ratio should be determined empirically for different DNA types.

Protocol: Single Molecule Localization Microscopy (SMLM) with Hoechst and DAPI

Principle: UV-induced photoconversion of Hoechst and DAPI creates green-emitting forms that exhibit stochastic blinking, enabling super-resolution imaging of chromatin nanostructure [9].

Materials:

- Hoechst 33258 or DAPI

- Oxygen scavenging system: glucose oxidase and catalase in glycerol

- Fixed cells or chromosomes on coverslips

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Stain fixed cells with Hoechst 33258 or DAPI using standard protocols.

- Imaging Buffer: Apply oxygen-scavenging imaging buffer to reduce blinking rate and increase signal detection [9].

- SMLM Acquisition:

- Use continuous 405 nm illumination (low intensity) to stochastically convert subsets of dyes to green-emitting form.

- Use 491 nm excitation to excite the green-emitting forms.

- Detect emission in green-yellow channel (585-675 nm).

- Record thousands of frames to accumulate sufficient single-molecule localization events.

- Image Reconstruction: Precisely localize individual molecule positions and reconstruct super-resolution image.

Notes:

- This approach enables chromatin imaging with ~15-25 nm localization precision [9].

- The optimized embedding medium increases detected signals by 50-fold compared to standard buffers [9].

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualizations

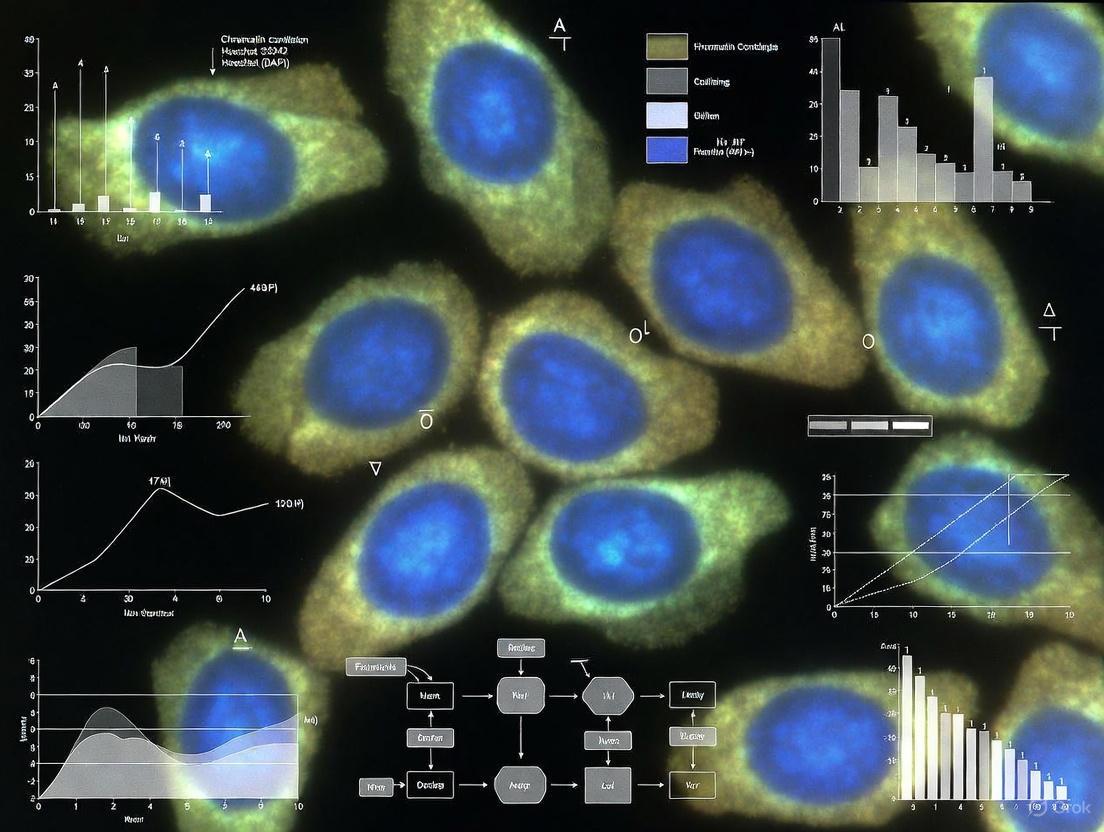

Diagram 1: Molecular Mechanism and Applications of Minor Groove Binding. The pathway illustrates the sequence-specific recognition of AT-rich DNA through minor groove binding, resulting in photophysical changes that enable various biological applications.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for FLIM-Based Chromatin Compaction Analysis. The flowchart details the complete process from sample preparation through FLIM data acquisition and analysis for assessing chromatin compaction status using DNA minor groove binders.

In fluorescence microscopy research, the structural organization of chromatin is not merely a background detail but a critical determinant of DNA function and accessibility. For researchers using ubiquitous DNA stains like Hoechst and DAPI, understanding how chromatin compaction influences dye binding and fluorescence properties is essential for accurate experimental interpretation. This application note explores the fundamental relationship between chromatin organization and the photophysical behavior of minor-groove binding dyes, providing structured protocols and quantitative frameworks for researchers investigating nuclear architecture in drug development and basic research contexts. The sensitivity of these dyes to the chromatin microenvironment creates both challenges and opportunities—while compaction-dependent fluorescence variations can complicate intensity-based quantification, they simultaneously enable advanced techniques like fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) to probe chromatin states in living cells without genetic modification [10] [2].

Core Principles: Chromatin Architecture and Dye Binding

Chromatin exists in a dynamic continuum of organizational states, from open, transcriptionally active euchromatin to highly condensed, silent heterochromatin. This structural variation profoundly impacts how small molecule dyes access and interact with their DNA targets. The nucleosome, comprising approximately 146 base pairs of DNA wrapped around a histone core, represents the fundamental repeating unit [2]. These nucleosomes further organize into higher-order structures of varying density, with heterochromatin characterized by larger, denser nucleosome "clutches" compared to euchromatin [11].

Minor groove binders like Hoechst and DAPI exhibit distinct binding preferences for AT-rich DNA sequences, but their accessibility to these preferred binding sites is sterically hindered by nucleosomal packaging [12]. In highly condensed heterochromatin, the minor groove faces inward toward histones in many nucleosomal configurations, creating a physical barrier to dye binding [12]. This reduced accessibility manifests experimentally as either diminished fluorescence intensity or altered fluorescence lifetime, depending on the detection modality. Consequently, the local chromatin landscape directly modulates the signal generated by these molecular probes, enabling researchers to deduce nuclear architecture from fluorescence readouts.

Quantitative Fluorescence Response to Chromatin Compaction

Fluorescence Lifetime Changes

Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) measures the average time a fluorophore remains in its excited state before emitting a photon, a parameter sensitive to the molecular environment but independent of local fluorophore concentration. This makes FLIM particularly valuable for investigating chromatin compaction, as lifetime changes can be directly attributed to environmental factors rather than mere dye accessibility.

Table 1: Fluorescence Lifetime Variations with Chromatin Compaction State

| Experimental Condition | Dye Used | Lifetime Change | Biological Interpretation | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperosmolar treatment (chromatin compaction) | Hoechst 34580 | ~2% decrease | Induced chromatin compaction reduces lifetime | [10] |

| Valproic acid treatment (chromatin decompaction) | Hoechst 34580 | ~1% increase | Histone hyperacetylation increases lifetime | [10] |

| Heterochromatic regions (constitutive heterochromatin) | DAPI | 2.21-2.57 ns | Shorter lifetime in condensed regions | [2] |

| Euchromatic regions | DAPI | 2.80 ± 0.09 ns | Longer lifetime in decondensed regions | [2] |

| X-ray irradiation (chromatin decompaction) | Hoechst 34580 | Increase measured | Radiation-induced global chromatin decompaction | [10] |

The mechanistic basis for these lifetime changes involves the molecular environment of DNA-bound dyes. In compacted heterochromatin, the dyes experience greater molecular crowding, potential self-quenching effects, and different dielectric environments, all of which can influence relaxation pathways from the excited state [10] [2]. The consistent observation of shorter lifetimes in condensed chromatin across multiple dye variants (Hoechst 34580, Hoechst 33258, Syto13, DAPI) suggests a common physical mechanism related to chromatin packing density rather than dye-specific chemistry.

Fluorescence Intensity-Based Measurements

While fluorescence intensity measurements are more accessible to most laboratories, they are inherently confounded by the dual factors of dye accessibility and local concentration. Nevertheless, when properly controlled, intensity readings can provide valuable insights into global chromatin accessibility.

Table 2: Intensity-Based Measurements of Chromatin Accessibility

| Measurement Approach | Key Parameter | Experimental Consideration | Biological Application | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Widefield microscopy | Mean nuclear fluorescence | Normalizes for cell cycle-dependent DNA content | Comparison of global chromatin accessibility between cell types | [12] |

| Flow cytometry | Integral fluorescence | Requires cell dissociation; difficult nuclear/cytoplasmic separation | Cell cycle analysis and population-level chromatin assessment | [12] |

| Enhanced fluorescence with SDS elution | Total fluorescence after elution | Requires cell fixation and dye elution | Highly sensitive cell quantification independent of metabolism | [13] |

| Tumor vs. normal cell comparison | Mean nuclear intensity | Normalization for DNA content essential | Tumor cells show increased global chromatin accessibility | [12] |

A critical methodological consideration is normalization for total DNA content, which varies throughout the cell cycle. The mean nuclear fluorescence intensity (average pixel intensity per nucleus) has been demonstrated to effectively normalize for these cell cycle-dependent variations, providing a more reliable metric for chromatin accessibility comparisons than total integrated intensity [12].

Experimental Protocols

FLIM-Based Chromatin Compaction Assay in Live Cells

This protocol enables quantitative measurement of chromatin compaction dynamics in living cells using Hoechst 34580 and fluorescence lifetime imaging, based on methodologies established in [10].

Reagents and Equipment:

- Hoechst 34580 stock solution (10 mM in DMSO)

- Appropriate cell culture medium

- Histone deacetylase inhibitors (e.g., valproic acid) for positive control

- Hypertonic medium (e.g., 4x PBS) for compaction control

- Time-domain FLIM system with time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC)

- Temperature-controlled live-cell imaging chamber

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Plate cells in glass-bottom dishes at 50-70% confluence 24 hours before imaging.

- Dye Loading: Add Hoechst 34580 to culture medium at final concentration of 1-2 µM. Incubate for 20-30 minutes at 37°C.

- Image Acquisition:

- Place samples on pre-warmed microscope stage with CO₂ control.

- Acquire FLIM data using multiphoton excitation at 740 nm or single-photon UV excitation.

- Set detector count rates to avoid pile-up effects (<1-2% of laser repetition rate).

- Collect sufficient photons (>1000 photons per pixel) for accurate lifetime fitting.

- Data Correction: Apply pile-up and counting loss corrections to raw TCSPC data using appropriate algorithms.

- Lifetime Analysis: Fit fluorescence decay curves to multi-exponential models using specialized software. Mean lifetime values are most relevant for chromatin compaction assessment.

- Validation: Include control samples with known chromatin modulators (e.g., 1-5 mM valproic acid for 24 hours for decompaction; hypertonic medium for 30-60 minutes for compaction).

Technical Notes: Pile-up effects significantly distort lifetime measurements even at moderate count rates in heterogeneous samples like cell nuclei. The application of real-time or post-processing correction algorithms is essential for accurate lifetime determination [10]. Hoechst 34580 is preferred over Hoechst 33342 for its superior lifetime sensitivity to chromatin states, though Syto13 represents an alternative excitable at 488 nm.

Fixed-Cell Chromatin Accessibility Assessment

This protocol adapts the intensity-based method for comparing global chromatin accessibility between cell populations, utilizing standard widefield microscopy [12].

Reagents and Equipment:

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Fixative (4% paraformaldehyde in PBS or 70% ethanol)

- Hoechst 33342 or DAPI staining solution (1 µg/mL in PBS)

- Permeabilization solution (0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS, if using paraformaldehyde fixation)

- Automated widefield microscope with 4x-10x objectives

Procedure:

- Cell Fixation:

- For adherent cells: Remove medium, wash with PBS, and fix with 4% PFA for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Alternatively, fix with 70% ethanol for 10 minutes at room temperature for better preservation of nuclear morphology.

- Permeabilization: If using PFA fixation, permeabilize cells with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes.

- Staining: Incubate cells with Hoechst 33342 or DAPI staining solution (1 µg/mL in PBS) for 15-30 minutes at room temperature, protected from light.

- Image Acquisition:

- Using an automated microscope with 4x or 10x objective, acquire images from multiple fields per condition.

- Ensure exposure time is set to avoid pixel saturation.

- Maintain identical acquisition parameters across all experimental conditions.

- Image Analysis:

- Segment nuclei using intensity thresholding and morphological operations.

- For each nucleus, calculate mean fluorescence intensity (average pixel value within nuclear mask).

- Exclude mitotic cells and apoptotic nuclei with condensed chromatin from analysis.

- Data Normalization: Normalize mean intensity values to control conditions included in each experiment.

Technical Notes: The mean nuclear fluorescence intensity parameter effectively normalizes for cell cycle-dependent DNA content variations [12]. This method has demonstrated increased chromatin accessibility in tumor versus normal cells and following oncogenic transformation. For precise cell cycle phase discrimination, cells can be pre-labeled with EdU or BrdU before fixation.

Enhanced Quantitative Cell Counting with DNA Dyes

This protocol describes a highly sensitive method for fixed cell quantification using SDS-enhanced fluorescence of DNA dyes, adapted from [13].

Reagents and Equipment:

- Hoechst 33342 or DAPI stock solutions

- Fixative (70% ethanol)

- Washing solution: 2 mM CuSO₄, 0.2 M CaCl₂, 2 M NaCl, 0.2% Tween 20, 50 mM citric acid (for Hoechst) or 2 mM CuSO₄, 0.5 M NaCl, 0.2% Tween 20, 20 mM citrate buffer, pH 5 (for DAPI)

- Elution solution: 2% SDS in 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7 (for Hoechst) or 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7 (for DAPI)

- Fluorescence plate reader (excitation ~370 nm, emission ~460 nm for DAPI, ~485 nm for Hoechst)

Procedure:

- Cell Fixation: Fix adherent cells with 70% ethanol for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Air Drying: Remove ethanol and air-dry cells for 20-30 minutes until no visible liquid remains.

- Staining: Add 100 µL/well (96-well plate) of 2 µM Hoechst 33342 or 3 µM DAPI in Tris-buffered saline. Incubate 30 minutes with gentle shaking.

- Washing: Wash cells three times with appropriate washing solution (5 minutes per wash for Hoechst, 2 minutes for DAPI).

- Buffer Rinse: Briefly rinse with 20 mM phosphate buffer (Hoechst) or Tris-buffered saline (DAPI).

- Elution and Signal Enhancement: Add 120 µL/well of elution solution containing 2% SDS. Incubate 15 minutes with shaking.

- Measurement: Transfer 100 µL aliquots to black well plate. Measure fluorescence with plate reader.

Technical Notes: The SDS elution step simultaneously extracts bound dye from DNA and provides up to 1000-fold fluorescence enhancement through micelle formation [13]. This method enables detection of as few as 50-70 human diploid cells and is compatible with prior immunocytochemistry or cell cycle analysis. The signal remains stable for at least 20 days at room temperature.

Visualization of Chromatin-Dye Interactions and Experimental Workflows

Molecular Mechanism of Chromatin-Dye Interaction

This diagram illustrates how chromatin compaction states influence dye accessibility at the molecular level. In decondensed euchromatin, nucleosomes are spaced further apart, allowing minor groove binders like Hoechst and DAPI greater access to their AT-rich binding sites, resulting in enhanced fluorescence output. Conversely, in condensed heterochromatin, tightly packed nucleosomes sterically hinder dye access to the minor groove, reducing both binding efficiency and subsequent fluorescence emission [10] [12] [2].

Experimental Workflow for Chromatin Compaction Analysis

This workflow outlines the key steps in designing and executing experiments to investigate chromatin compaction using DNA-binding dyes. The protocol accommodates both live-cell FLIM approaches and fixed-cell intensity measurements, with optional inclusion of chromatin-modulating treatments for experimental validation [10] [12] [2]. Standardization of staining and imaging parameters across experimental conditions is critical for reliable comparisons.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents for Chromatin Accessibility Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application Notes | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Stains | Hoechst 33342, Hoechst 34580, Hoechst 33258, DAPI | Live/fixed cell staining; concentration-dependent binding modes | Hoechst 33342 preferred for live cells; DAPI for fixed cells [5] [14] |

| Chromatin Modulators | Valproic acid (HDACi), Curaxin CBL0137, Hyperosmotic solution | Experimental controls for compaction/decompaction | HDACi induces global chromatin decompaction; hyperosmolarity causes compaction [10] [12] |

| Fixation Agents | 4% Paraformaldehyde, 70% ethanol, Methanol | Preservation of nuclear architecture | Ethanol fixation preferred for DNA quantification; formaldehyde may reduce signal [13] |

| Signal Enhancers | SDS micelle solutions | Fluorescence enhancement for sensitive detection | Provides up to 1000-fold signal increase; enables detection of 50-70 cells [13] |

| Advanced Probes | SiR-Hoechst, Hoechst-IR, MCPH1-BRCT-eCR | Specialized applications: super-resolution, in vivo imaging, DNA damage tracking | SiR-Hoechst enables far-red DNA staining; eCR probes detect DNA damage [15] [14] |

Advanced Techniques and Future Directions

Beyond conventional microscopy, several advanced approaches are expanding our ability to investigate chromatin organization. Fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) provides environmental sensing beyond mere dye accumulation, detecting subtle changes in chromatin packing through nanosecond-scale lifetime variations [10] [2]. Emerging label-free techniques like interferometric scattering correlation spectroscopy (iSCORS) probe chromatin condensation dynamics without exogenous labels by measuring diffusion coefficients and density fluctuations in live cells [16]. For DNA damage research, engineered chromatin readers (eCRs) such as MCPH1-BRCT domains specifically bind γH2AX marks, enabling real-time tracking of damage response and repair dynamics in living cells and organisms [15]. Super-resolution variants like SiR-Hoechst combine the specificity of minor-groove binding with far-red fluorescence compatible with STED microscopy, achieving resolution beyond the diffraction limit [14]. Additionally, deep learning approaches are increasingly applied to enhance image reconstruction, segmentation, and analysis of chromatin architecture data, particularly with complex super-resolution datasets [11].

Each methodology offers complementary advantages: FLIM provides environmental sensing without intensity dependence, label-free techniques enable long-term observation without phototoxicity, specialized probes facilitate specific process tracking, super-resolution methods reveal nanoscale organization, and computational approaches extract maximal information from complex imaging data. The optimal technique selection depends on specific research questions, balancing requirements for spatial resolution, temporal dynamics, molecular specificity, and experimental throughput.

The accurate visualization of nuclear chromatin is a cornerstone of cell biology research, particularly in studies of cell cycle status, nuclear morphology, and chromatin condensation. The fluorescent dyes Hoechst 33342 and 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) are among the most vital tools for these investigations, providing high specificity for DNA through their binding to AT-rich regions in the minor groove of double-stranded DNA. Their utility spans diverse applications from basic nuclear counting in fluorescence microscopy to advanced analyses of apoptotic condensation and cell cycle progression in drug development screens. A comprehensive understanding of their fundamental photophysical properties—including excitation and emission profiles, binding characteristics, and photostability—is paramount for experimental design and data interpretation. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these critical nuclear stains, along with validated protocols and visualization guidelines, to support researchers in employing these reagents effectively and accurately within the broader context of chromatin dynamics research.

Table 1: Core Photophysical Properties of Hoechst 33342 and DAPI

| Property | Hoechst 33342 | DAPI |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Excitation Maximum | ~350 nm [17] | ~358 nm [18] |

| Primary Emission Maximum | ~461 nm [17] | 454 - 461 nm [18] |

| Standard Microscope Filter Set | DAPI [17] | DAPI or UV [18] |

| Cell Permeability | Cell-permeant [17] | Impermeant in live cells; requires fixation [18] |

| Primary Binding Target | AT-rich regions of dsDNA [17] | AT-rich regions of dsDNA [18] |

| Fluorescence Quantum Yield | Increases upon DNA binding | Increases upon DNA binding |

| Common Research Applications | Live-cell imaging, cell cycle studies, apoptosis (condensed nuclei) [17] | Fixed-cell imaging, nuclear counterstain in multiplex assays, chromosome staining [18] |

Photophysical Characteristics and Spectral Profiles

The utility of Hoechst 33342 and DAPI stems from their significant enhancement in fluorescence quantum yield upon binding to DNA. While both dyes are excitable with ultraviolet (UV) light and emit in the blue spectrum, subtle differences in their photophysical behaviors necessitate careful selection for specific experimental conditions. Hoechst 33342 is celebrated for its cell permeability, making it the stain of choice for live-cell applications, such as tracking nuclear dynamics in real time or sorting cells based on DNA content via flow cytometry. Its excitation maximum at approximately 350 nm and emission maximum at 461 nm produce a robust blue fluorescence that is easily separable from fluorophores like GFP and RFP using standard DAPI filter sets [17].

DAPI displays a nearly identical spectral profile, with an excitation maximum around 358 nm and an emission maximum between 454 and 461 nm. However, it is generally not cell-permeant in viable cells, confining its primary use to fixed samples where membrane disruption allows access to the nucleus [18]. A critical and often overlooked photophysical phenomenon for both dyes is photoconversion. Upon exposure to UV excitation light, these dyes can be converted into species with distinct excitation and emission profiles. DAPI and Hoechst dyes can be photoconverted into forms that are excited by blue light and emit green fluorescence, and further into forms that are excited by green light and emit red fluorescence. This conversion can occur rapidly, in some cases with less than 10 seconds of UV exposure [19]. This has profound implications for multiplexed imaging experiments, as the photoconverted signal can lead to false-positive colocalization or channel bleed-through, potentially misrepresenting the subcellular localization of co-stained targets imaged with green or red fluorescent probes.

Table 2: Advanced Properties and Experimental Considerations

| Characteristic | Hoechst 33342 | DAPI |

|---|---|---|

| Stock Solution Solvent | Deionized water (with sonication) [17] | Aqueous buffer (e.g., PBS, water) [18] |

| Working Solution Diluent | Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or culture medium [17] | Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or mounting medium [18] |

| Recommended Staining Time | 5 - 10 minutes [17] | 5 - 30 minutes (protocol-dependent) [18] |

| Photoconversion Risk | Yes; to green- and red-emitting forms with UV exposure [19] | Yes; to green- and red-emitting forms with UV exposure [19] |

| Signal Quenched By | BrdU [17] | N/A (Information not in search results) |

| Major Safety Consideration | Known mutagen; handle with care [17] | N/A (Information not in search results) |

Diagram 1: DAPI/Hoechst photoconversion pathway and artifact generation.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Hoechst 33342 Staining Protocol for Fluorescence Microscopy

This protocol is designed for staining adherent or suspension cells cultured on microscopy-suitable vessels (e.g., glass-bottom dishes, chambered coverslips) [17].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Hoechst 33342 Stock Solution (10 mg/mL): Dissolve 100 mg of Hoechst 33342 (trihydrochloride, trihydrate) in 10 mL of deionized water (dH₂O) to achieve a 10 mg/mL (16.23 mM) concentration. Note: The dye has poor solubility and may require sonication to fully dissolve. Aliquot and store protected from light at 2–6°C for up to 6 months or at ≤ –20°C for longer-term storage [17].

- Hoechst Staining Solution (Working Solution): Dilute the stock solution 1:2,000 in PBS immediately before use. For example, add 5 µL of stock to 10 mL of PBS to create a 5 µg/mL working solution [17].

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Appropriate Cell Culture Medium

Labeling Procedure:

- Culture and Prepare Cells: Grow cells to the desired confluence in an appropriate microscopy vessel.

- Prepare Staining Solution: Dilute the Hoechst stock solution in PBS to create the working solution. Protect from light.

- Apply Stain: Carefully remove the culture medium from the cells. Add a sufficient volume of the Hoechst staining solution to completely cover the monolayer of cells.

- Incubate: Incubate the cells at 37°C (or room temperature) for 5 to 10 minutes, ensuring the vessel is protected from light to prevent photobleaching.

- Rinse: Remove the staining solution. Wash the cells gently but thoroughly with pre-warmed PBS, three times, to remove any unbound dye.

- Image: Replace the PBS with fresh culture medium or a suitable live-cell imaging buffer. Acquire images using a fluorescence microscope equipped with a DAPI light cube (Ex/Em ~350/461 nm) [17].

Protocol Note: The working concentration and incubation time can be optimized for specific cell types. Over-staining can lead to a green haze in the background due to emission from unbound dye [17].

DAPI Staining Protocol for Fixed Cells

This protocol is optimized for visualizing nuclei in cells fixed with paraformaldehyde or other cross-linking agents [18].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- DAPI Stock Solution: Commercially available or prepared as a concentrated aqueous solution (e.g., 1-5 mg/mL).

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Mounting Medium: Use an anti-fade mounting medium (e.g., Vectashield, SlowFade) to preserve fluorescence.

- Fixative: Typically, 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS.

Labeling Procedure:

- Fix Cells: Culture and grow cells on coverslips. Aspirate the medium and wash gently with PBS. Fix the cells with 4% PFA for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Wash: Remove the fixative and wash the cells three times with PBS, 5 minutes per wash.

- Prepare DAPI Working Solution: Dilute the DAPI stock solution in PBS to a common working concentration of 1-5 µg/mL.

- Stain: Apply the DAPI working solution to the fixed cells on the coverslip. Incubate for 5 to 30 minutes at room temperature, protected from light.

- Final Wash: Remove the staining solution and perform a final wash with PBS (2 x 5 minutes).

- Mount: Briefly air-dry the coverslip (or mount directly), and mount it onto a glass microscope slide using an anti-fade mounting medium. Seal the edges with clear nail polish if necessary.

- Image: Acquire images using a fluorescence microscope with a DAPI or UV filter set [18].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for live-cell and fixed-cell staining.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Nuclear Staining

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hoechst 33342 | Cell-permeant nuclear counterstain for live and fixed cells. Distinguishes condensed nuclei in apoptosis. | Available as powder (H1399) or solution (H3570) [17]. |

| DAPI | Nuclear counterstain for fixed cells. Provides high contrast for nuclear morphology. | Often supplied in mounting media or as a concentrate [18]. |

| Anti-fade Mounting Medium | Preserves fluorescence signal during imaging by reducing photobleaching. | E.g., Vectashield, SlowFade Gold [19]. Critical for publication-quality images. |

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Cross-linking fixative that preserves cellular architecture for fixed-cell staining. | Typically used at 4% in PBS. Requires careful handling. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Isotonic buffer for washing cells, preparing staining solutions, and as a diluent. | Standard pH of 7.4 to maintain physiological conditions. |

Data Visualization and Color Accessibility

Effective presentation of fluorescence microscopy data is critical for accurate communication of scientific findings, especially considering that a significant portion of the audience (up to 8% of males and 0.5% of females) may have a color vision deficiency [20]. The default red-green color merge, common in many multicolor images, is particularly problematic as it becomes indistinguishable for individuals with the most common forms of color blindness [21] [20].

Best Practices for Accessible Image Presentation:

- Show Individual Channels: Always present grayscale images for each individual fluorescent channel alongside the merged image [22] [20]. The human eye is more sensitive to intensity changes in grayscale, which aids in discerning structural details and subtle signal differences [23] [21].

- Choose Accessible Color Merges: Replace the classic red-green combination with color-blind-friendly alternatives. For two-color images, use Green/Magenta, Cyan/Red, or Blue/Yellow [22] [21] [20]. For three-color images, a Magenta/Yellow/Cyan merge is a robust alternative [22] [20].

- Simulate Color Blindness: Use software tools to check your images. In ImageJ/Fiji, use

Image > Color > Dichromacy. In Adobe Photoshop, useView > Proof Setup > Color Blindness. Standalone tools like Color Oracle are also available [22] [20]. - Optimize Image Contrast: Apply contrast stretching (e.g., "autoscale") to ensure the dynamic range of your image data is fully utilized for display. This improves feature visibility without altering the underlying spatial information [23]. Avoid excessive manipulation that leads to clipping of relevant data.

By adhering to these visualization guidelines, researchers ensure their data is interpretable by the broadest possible audience, minimizing ambiguity and strengthening the impact of their published work.

Chromatin organization into euchromatin and heterochromatin represents a fundamental regulatory layer for genomic function in eukaryotic cells. While historically distinguished by differential staining intensity with DNA-binding dyes, the underlying biophysical principles governing these staining patterns are complex and quantitatively informative. This application note details how fluorescent dyes, particularly Hoechst 33258 and DAPI, serve as sensitive reporters of chromatin condensation states, moving beyond simple morphological staining to provide quantitative insights into nanoscale nuclear architecture. The response of these dyes is not merely a function of DNA concentration but is profoundly influenced by local chromatin compaction, base-sequence context, and the dynamic molecular environment within the nucleus [24] [2]. Advanced fluorescence methodologies, including Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy and interferometric scattering techniques, now enable researchers to quantify these subtle dye-environment interactions in live cells, providing unprecedented insight into nuclear organization and its functional consequences [25] [16]. This guide provides detailed protocols and analytical frameworks for leveraging these tools in chromatin research and drug development.

Fundamental Principles of Chromatin-Dye Interactions

The differential staining of heterochromatin and euchromatin by DNA-binding fluorophores arises from a combination of physical and molecular factors. Heterochromatin is characterized by a significantly higher DNA density—5.5 to 7.5-fold greater than euchromatic regions—while the difference in total material density (including proteins and RNAs) is surprisingly modest at only 1.53-fold [24]. This dense DNA packing creates a molecular environment that influences both the binding kinetics and the photophysical properties of intercalating and groove-binding dyes.

Hoechst 33258 and DAPI preferentially bind the minor groove of AT-rich DNA sequences, with Hoechst exhibiting particularly high affinity for the AATT sequence [26]. This binding specificity is crucial because heterochromatic regions often display distinct base composition. Upon binding, these dyes experience microenvironmental changes that affect their fluorescence emission properties. In highly condensed heterochromatin, factors such as chromatin packing density, proximity to quenching species, and local viscosity can alter fluorescence quantum yield and lifetime [2]. DAPI exhibits a markedly higher quantum yield when bound to DNA (φf = 0.92) compared to its unbound state (φf = 0.04), making its emission exquisitely sensitive to the chromatin environment [2]. These phenomena transform simple stains into quantitative sensors of nuclear nano-architecture.

Diagram 1: Chromatin-Dye Interaction Workflow. This diagram illustrates the pathway from fundamental dye and chromatin properties through their molecular interaction to the resulting detectable signals and their biological interpretation. Key factors influencing each step are shown, including the 1.53-fold higher density of heterochromatin [24].

Quantitative Dye Responses to Chromatin States

Fluorescence Lifetime Variations

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy reveals that DAPI's excited state lifetime serves as a sensitive indicator of chromatin compaction. In human metaphase chromosomes, heteromorphic regions (highly condensed constitutive heterochromatin) of chromosomes 1, 9, 15, 16, and Y show statistically significant shorter DAPI lifetime values compared to less condensed regions [2].

Table 1: DAPI Fluorescence Lifetime in Human Chromosomes

| Chromosomal Region | DAPI Fluorescence Lifetime (ns) | Chromatin State |

|---|---|---|

| General Chromosome Arms | 2.80 ± 0.09 | Less condensed euchromatin |

| Pericentromeric Regions (Chr 1, 16, Y) | 2.57 ± 0.06 | Constitutive heterochromatin |

| Pericentromeric Regions (Chr 9, 15) | 2.41 ± 0.06 | Constitutive heterochromatin |

| Specific Region (Chr 9) | 2.21 ± 0.05 | Highly condensed heterochromatin |

These lifetime differences persist across cell types (B-lymphocytes, HeLa, lung fibroblasts) and reflect underlying variations in chromatin structure rather than preparation artifacts [2]. The shortened lifetime in heterochromatin likely results from chromatin-induced quenching effects and the unique molecular environment of densely packed DNA.

Binding Affinity and Specificity

The binding behavior of Hoechst and DAPI is governed by sequence-specific interactions that influence their distribution across chromatin domains. Quantitative studies using hairpin oligonucleotides demonstrate that Hoechst 33258 exhibits a distinct affinity hierarchy for different (A/T)₄ binding sites [26].

Table 2: Sequence-Specific Binding Affinities of Hoechst 33258 and DAPI

| (A/T)₄ Sequence | Relative Affinity (Hoechst 33258) | Relative Affinity (DAPI) |

|---|---|---|

| AATT | Highest | High |

| TAAT | High | High |

| ATAT | High | High |

| TATA | Lower | Moderate |

| TTAA | Lower | Moderate |

Hoechst 33258 shows greater sensitivity to sequence variation compared to DAPI, with its dissociation rate (k₋₁) largely determining binding strength [26]. This molecular-level specificity directly influences macroscopic staining patterns in cellular chromatin, as heterochromatic and euchromatic regions often differ in their local sequence composition.

Advanced Methodologies for Chromatin Analysis

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) Protocol

Principle: FLIM measures the average time a fluorophore remains in its excited state before emitting a photon, which is sensitive to the molecular environment but independent of fluorophore concentration [2]. This makes it ideal for studying chromatin compaction through DAPI or Hoechst lifetime variations.

Sample Preparation:

- Use cultured human cells (B-lymphocytes GM18507, HeLa, or CCD37LU lung fibroblasts)

- Synchronize cell cycle with 0.3 mg/ml thymidine for 17 hours

- Arrest mitotic cells with 0.2 μg/ml colcemid for 16 hours

- Apply hypotonic treatment with 0.075 M KCl for 5 minutes

- Fix cells in 3:1 methanol:acetic acid with three solution changes

- Spread chromosomes on glass slides using hanging drop method

- Stain with 4 μM DAPI or Hoechst 33258 for 5 minutes

- Rinse with 1× PBS for 5 minutes and mount with deionized water [2]

Data Acquisition:

- Use multiphoton excitation for FLIM imaging

- Measure fluorescence lifetime at each image pixel with temporal resolution of nanoseconds

- Collect sufficient photons per pixel for statistically robust lifetime fitting

- For comparative studies, maintain consistent imaging parameters across samples

Data Analysis:

- Fit lifetime decays to multi-exponential models as needed

- Generate lifetime maps to visualize spatial variations in chromatin compaction

- Identify heterochromatic regions based on significantly shortened lifetimes

- Perform statistical analysis to confirm differences between chromatin states [2]

Interferometric Scattering Correlation Spectroscopy (iSCORS)

Principle: iSCORS is a label-free technique that detects nanoscale chromatin fluctuations by analyzing dynamic light scattering signals from unlabeled live cells [16]. It measures diffusion coefficients and density of chromatin, enabling quantitative assessment of condensation states without fluorescent labels.

Instrument Setup:

- Custom-built interferometric scattering microscope in transmission geometry

- High numerical aperture condenser (NA 0.8) and objective (NA 1.49)

- Laser illumination with acousto-optic deflectors for beam scanning

- High-speed camera acquisition at 5000 frames per second

- Simultaneous epifluorescence channel for correlation studies [16]

Measurement Protocol:

- Culture mammalian cells (e.g., U2OS) on appropriate substrates

- Acquire transmission images at high frame rates

- Calculate interference contrast (C) maps using flat-field correction

- Extract dynamic light scattering signals (C_DLS) from temporal fluctuations

- Analyze correlation times and fluctuation magnitudes

- Relate diffusion characteristics to chromatin condensation states [16]

Applications:

- Long-term monitoring of chromatin dynamics in live cells

- Detection of spontaneous chromatin condensation fluctuations

- Assessment of chromatin response to transcription inhibition

- Study of cell-to-cell heterogeneity in chromatin organization

Diagram 2: Advanced Chromatin Analysis Technologies. This diagram compares four advanced methodologies for studying chromatin condensation, highlighting the unique output parameters each technique provides for quantitative analysis of heterochromatin and euchromatin [24] [25] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Technologies

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Chromatin Condensation Studies

| Reagent/Technology | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) | DNA staining for chromatin visualization | High quantum yield when bound to DNA (φf = 0.92); preferential AT-binding; lifetime sensitive to environment [2] |

| Hoechst 33258 | DNA staining for chromatin visualization | Bis-benzimidazole derivative; high specificity for AATT sequences; bright fluorescence [26] |

| Fluorescent Protein-tagged Histones | Live-cell chromatin labeling | Enable FRET-based compaction assays; compatible with FLIM measurements [25] |

| OI-DIC Microscopy | Total density mapping in live cells | Measures optical path differences; quantifies density without staining [24] |

| iSCORS Microscopy | Label-free chromatin dynamics | Detects nanoscale fluctuations via scattering; millisecond temporal resolution [16] |

| FRET-FLIM Assay | Chromatin compaction measurement | Uses H2B-EGFP/mCherry pair; detects nucleosome proximity changes [25] |

| Structured Illumination Microscopy | Super-resolution chromatin imaging | Bypasses diffraction limit; reveals chromatin nanostructures [27] |

Experimental Applications and Workflows

FRET-FLIM Assay for Chromatin Compaction

The FRET-FLIM assay utilizing fluorescent protein-tagged histones provides a robust method for measuring relative chromatin compaction levels in live cells. This approach exploits the distance-dependent nature of Förster Resonance Energy Transfer between fluorophores tagged to separate nucleosomes [25].

Cell Line Generation:

- Establish double stable HeLa cell line (HeLaH2B-2FP) coexpressing:

- Histone H2B fused at C-terminus to EGFP (donor)

- Histone H2B fused at N-terminus to mCherry (acceptor)

- Verify proper incorporation of tagged histones into nucleosomes

- Confirm that not all nucleosomes contain both fluorophores [25]

Experimental Workflow:

- Culture HeLaH2B-2FP cells under appropriate conditions

- Perform FLIM measurements using multiphoton excitation

- Measure fluorescence lifetime of donor (EGFP) fluorophore

- Calculate FRET efficiency from reduced donor lifetime

- Generate FRET efficiency maps across nucleus

- Identify regions with different chromatin compaction states

- Treat with controls to validate assay sensitivity:

- Trichostatin A (decreases compaction)

- ATP depletion (increases compaction) [25]

Data Interpretation:

- Higher FRET efficiency indicates closer nucleosome proximity and greater compaction

- Interphase cells typically show three distinct FRET populations (low, medium, high)

- Mitotic chromosomes exhibit varying compaction levels throughout their length

- Maximum compaction occurs in late anaphase [25]

Monitoring Chromatin Dynamics in Live Cells

The integration of multiple techniques provides complementary insights into chromatin dynamics. While fluorescence-based methods offer molecular specificity, label-free approaches enable long-term observation without phototoxic effects.

Correlative iSCORS and Fluorescence Protocol:

- Culture cells expressing fluorescent histone tags or stained with viable DNA dyes

- Acquire simultaneous iSCORS and fluorescence data using integrated system

- Correlate scattering fluctuations with fluorescence-based compaction metrics

- Monitor chromatin responses to perturbations over extended periods (hours to days)

- Analyze heterogeneity in chromatin dynamics across cell populations [16]

Applications in Drug Discovery:

- Screen compounds affecting chromatin modifiers (HDAC inhibitors, etc.)

- Quantify chromatin remodeling during stem cell differentiation

- Assess nuclear changes in DNA damage response

- Evaluate epigenetic therapeutics in disease models

The sophisticated application of DNA-binding dyes and advanced imaging technologies has transformed our understanding of chromatin organization. Moving beyond simple staining, techniques like FLIM, iSCORS, and FRET-FLIM enable quantitative, dynamic assessment of chromatin condensation states in living cells. The differential responses of Hoechst and DAPI to heterochromatin and euchromatin—manifested through fluorescence lifetime variations, binding affinity differences, and intensity distributions—provide rich biochemical and biophysical information about nuclear architecture.

Future developments will likely focus on improved temporal resolution for capturing rapid chromatin dynamics, enhanced multiplexing capabilities for simultaneous monitoring of multiple nuclear components, and integration with omics technologies to correlate structural observations with molecular profiles. The continuing refinement of label-free techniques like iSCORS will facilitate long-term studies of chromatin remodeling during crucial processes like cellular differentiation, senescence, and transformation. These advances will further establish chromatin condensation analysis as a vital tool in basic research and drug development, particularly in the growing field of epigenetic therapeutics.

From Basic Staining to Advanced Assays: Practical Protocols for Chromatin Analysis

Optimal Staining Protocols for Fixed vs. Live Cells

Fluorescence microscopy is an indispensable tool in cell biology, enabling researchers to visualize subcellular structures and dynamics. Among the most critical steps in preparing samples for such imaging is the effective staining of cellular DNA, which allows for the identification of individual cells, assessment of nuclear morphology, and analysis of the cell cycle. The bis-benzimide dyes Hoechst and DAPI are the most widely used blue fluorescent nuclear counterstains in biological research [5] [28]. Their role is particularly crucial in the context of chromatin condensation research, where precise nuclear staining is a prerequisite for quantifying compaction states and understanding their functional implications in processes like stem cell differentiation and transcriptional regulation [16] [29].

A fundamental principle that researchers must appreciate is that the choice between these dyes and their staining protocols is not arbitrary but is critically dependent on whether the cells under investigation are live or fixed. Selecting the appropriate dye and optimizing the protocol are essential for maintaining cell viability, achieving sufficient staining intensity, and minimizing experimental artifacts. This application note provides a detailed, practical guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the optimal use of Hoechst and DAPI, framed within the advanced context of live-cell chromatin dynamics research.

Dye Characteristics and Selection Criteria

Hoechst and DAPI are both minor-groove binding dyes with a strong preference for A/T-rich regions of DNA [5]. Both experience a significant increase in fluorescence quantum yield upon binding to DNA, allowing for specific nuclear staining. Despite these similarities, key differences dictate their suitability for specific applications.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Hoechst and DAPI for Cell Staining

| Characteristic | Hoechst 33342 | Hoechst 33258 | DAPI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Live-cell imaging [5] | Live & fixed cells [5] | Fixed-cell staining [5] |

| Cell Permeability | High [30] | Moderate [5] | Low [5] [30] |

| Relative Toxicity | Lower [5] [30] | Lower [5] | Higher [5] [30] |

| Recommended Staining Concentration | 1 µg/mL [5] | 1 µg/mL [5] | 1 µg/mL (fixed); 10 µg/mL (live) [5] |

| Excitation/Emission (in nm) | ~350/461 [5] | ~352/461 [5] | ~358/461 [5] |

| Photoconversion Issues | Yes, with UV exposure [5] | Yes, with UV exposure [5] | Yes, with UV exposure [5] |

Key Selection Guidelines

- For Live-Cell Experiments: Hoechst 33342 is the dye of choice. Its high cell permeability allows it to efficiently label nuclei in living cells without requiring membrane disruption [5] [30]. Recent studies have demonstrated that with modern sensitive microscope cameras, long-term live-cell imaging (LCI) is possible using remarkably low, non-cytotoxic concentrations of Hoechst 33342 (7–28 nM) without affecting proliferation, viability, or signaling pathways [31].

- For Fixed-Cell Experiments: DAPI is often preferred. As it is less cell-permeant and more toxic than Hoechst dyes, it is ideally suited for use after cells have been fixed [5]. Its stability in dilute solutions also allows it to be incorporated directly into antifade mounting media for permanent preservation of samples [5].

Detailed Staining Protocols

Staining of Live Cells with Hoechst 33342

This protocol is optimized for visualizing nuclei in live cells for short-term imaging or long-term tracking of chromatin dynamics.

Diagram 1: Workflow for live cell staining with Hoechst 33342

Protocol Steps:

- Dye Solution Preparation: Prepare a 10 mg/mL stock solution of Hoechst 33342 in deionized water. Sonicate if necessary to dissolve completely. This stock can be stored at 4°C for up to 6 months or at -20°C for longer periods [17]. For staining, dilute the stock in the cell culture medium or PBS to a final working concentration of 1 µg/mL [5]. Avoid storing dilute solutions as the dye may precipitate or adsorb to container walls over time [5].

- Staining Procedure:

- For adherent cells, remove the existing culture medium and replace it with the pre-warmed staining solution.

- Incubate for 5–15 minutes at room temperature or 37°C, protected from light [5] [17].

- For minimal disturbance, an alternative method is to add a 10X concentrate of the dye directly to the culture medium (resulting in the same final concentration) and mix immediately and gently [5].

- Post-Staining and Imaging: After incubation, the staining solution can be removed and replaced with fresh culture medium, or cells can be imaged directly in the staining solution [17]. Washing with PBS is optional but can reduce background fluorescence [17].

Critical Considerations for Live-Cell Imaging:

- Low-Toxicity Staining: For extended time-lapse experiments over days, recent evidence shows that concentrations as low as 14 nM (approximately 8 ng/mL) are sufficient for accurate cell counting without impacting proliferation or health [31]. The traditional dogma that Hoechst is only for endpoint analysis is outdated with modern microscopy systems [31].

- Cell Health: Hoechst staining can induce apoptosis or show toxicity in some cell types over extended periods [5]. It is crucial to use the lowest effective concentration and minimize light exposure to avoid phototoxicity.

- Advanced Context: In chromatin condensation research, live-cell staining with Hoechst enables the correlation of nuclear morphology with dynamic cellular processes. For instance, intravital imaging of stem cell differentiation has revealed that global chromatin compaction state reflects differentiation status and transitions gradually over days [29].

Staining of Fixed Cells or Tissue Sections with DAPI

This protocol is designed for robust nuclear counterstaining in fixed samples, commonly used in immunofluorescence and studies of nuclear architecture.

Diagram 2: Workflow for fixed cell staining with DAPI

Protocol Steps:

- Fixation: Fix cells according to your standard protocol. A 10-minute fixation with 70% ethanol at room temperature is effective and preserves the sample for subsequent staining [13]. Air-drying for 20-30 minutes after fixation can help adherent cells remain attached during subsequent washes [13].

- Dye Solution Preparation: Dilute DAPI in PBS to a final working concentration of 1 µg/mL [5]. DAPI is stable in dilute solutions and can also be incorporated directly into antifade mounting media (e.g., EverBrite Mounting Medium with DAPI) for a one-step staining and mounting process [5].

- Staining Procedure: Apply the DAPI staining solution to the fixed cells or tissue sections and incubate for at least 5 minutes at room temperature, protected from light [5].

- Post-Staining and Mounting: Remove the DAPI solution. A wash with PBS is optional but not required for specific staining [5]. Mount the samples using an appropriate antifade mounting medium if DAPI was not already included.

Advanced Application and Enhancement:

- Signal Enhancement for Quantification: A highly sensitive method for quantifying fixed adherent cells involves staining with DAPI or Hoechst 33342, followed by incubation in a solution containing 2% SDS [13]. This procedure elutes the dye from DNA and enhances its fluorescence intensity up to 1,000-fold, allowing detection of as few as 50-70 human diploid cells. This method is compatible with immunocytochemistry and provides a stable signal for weeks [13].

- Research Context: In fixed samples, DAPI staining is a cornerstone for quantifying chromatin condensation. Studies comparing H2B-GFP fluorescence with Hoechst staining in fixed tissue have validated that fluorescence intensity provides a reliable readout of large-scale chromatin architecture, distinguishing heterochromatin from euchromatin [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Nuclear Staining and Chromatin Research

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hoechst 33342 | Live-cell nuclear staining and cell cycle analysis [5] [17]. | Cell-permeant; use at 1 µg/mL; optimal for long-term LCI at low nM concentrations [31]. |

| DAPI (dilactate salt) | Fixed-cell nuclear counterstaining [5]. | More soluble form; use at 1 µg/mL for fixed cells; can be added to mounting media. |

| Antifade Mounting Medium | Preserves fluorescence and prevents photobleaching during microscopy. | Available with or without DAPI; hardset versions can reduce photoconversion [5]. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Fluorescence enhancement for quantitative assays on fixed cells [13]. | Elutes DNA-bound dye and dramatically boosts signal intensity in a homogeneous solution. |

| p-Phenylenediamine (PPD) | Antifade agent for homemade mounting media [32]. | Protect from light; discard if solution turns dark. |

| Condensin Complex Inhibitors | Tool for probing mechanisms of chromatin condensation [33]. | Essential for functional studies linking structure to function. |

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

- Photoconversion: A significant but often overlooked issue with both DAPI and Hoechst is photoconversion upon exposure to UV light. This can cause the dyes to fluoresce in green or red channels, leading to crosstalk [5]. Mitigation strategies include imaging the green channel before switching to the DAPI channel, moving to an unexposed field of view for subsequent channels, and using hardset mounting media instead of glycerol-based media [5].

- Staining of Microbes: Staining bacteria or yeast with these dyes requires higher concentrations (12–15 µg/mL) and longer incubation times (∼30 minutes) as they stain more dimly than mammalian cells [5]. In S. cerevisiae, both dyes preferentially stain dead cells [5].

- Alternative Stains: For researchers facing issues with photoconversion or requiring different colors for multiplexing, alternative nuclear stains like NucSpot Live Stains (available in green and far-red) or RedDot1 (far-red) offer viable alternatives for specific applications [5].

The optimal staining of nuclei, whether in live or fixed cells, is a foundational technique that supports a vast range of research, from basic cell counting to advanced studies of chromatin condensation dynamics. The critical takeaway is the clear distinction in dye selection: Hoechst 33342 for live-cell applications due to its permeability and lower toxicity at optimized concentrations, and DAPI for fixed-cell staining due to its excellent performance and compatibility with mounting protocols. By adhering to these detailed protocols and considering the advanced troubleshooting tips, researchers can obtain reliable, high-quality data that accurately reflects nuclear architecture and dynamics, thereby strengthening findings in chromatin research and drug development.

Quantifying Chromatin Condensation with Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM)

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) is a powerful technique that measures the average time a fluorophore remains in its excited state before emitting a photon, a property that is largely independent of fluorophore concentration and excitation intensity [34] [35]. This makes it exceptionally suitable for investigating chromatin condensation states in living cells, as it can detect subtle environmental changes around DNA-binding dyes such as Hoechst and DAPI. Chromatin undergoes dynamic structural changes, transitioning between condensed (heterochromatin) and decondensed (euchromatin) states, which are crucial for regulating essential cellular processes like gene expression and DNA repair [2]. The organization of chromatin is intimately linked to cellular function, with alterations in chromatin condensation being a key biomarker in epigenetic research, cellular differentiation, and drug development [36]. FLIM provides a unique, quantitative window into these processes by measuring how the fluorescence lifetime of DNA-bound dyes changes in response to variations in chromatin compaction, offering a robust method to assess nuclear architecture in live cells without the need for genetic modification [10].

Principle of FLIM-Based Chromatin Assessment

The fundamental principle underlying FLIM-based chromatin assessment is the sensitivity of a fluorophore's lifetime to its local molecular environment. When a DNA-binding dye like Hoechst or DAPI intercalates into the DNA structure, its fluorescence lifetime is influenced by the physical compactness of the surrounding chromatin [2] [10]. Highly condensed heterochromatin presents a more restricted, molecularly crowded environment for the bound fluorophore. This can alter the dye's emission rate constant through various mechanisms, including increased quenching interactions or changes in local viscosity, ultimately resulting in a shorter fluorescence lifetime. Conversely, in decondensed euchromatin, the fluorophore experiences a less constrained environment, which typically manifests as a longer fluorescence lifetime [10]. This lifetime change provides a direct, quantitative readout of the local chromatin compaction state.

A significant advantage of using fluorescence lifetime over fluorescence intensity is its robustness against common artifacts in microscopy. FLIM measurements are not affected by fluctuations in excitation light intensity, photobleaching, variations in dye concentration, or light scattering within the sample [34] [10]. This makes FLIM a more reliable and quantitative technique for monitoring dynamic chromatin changes in living cells, as confirmed by studies showing that the coefficient of variation for fluorescence lifetime is smaller than that for fluorescence intensity in cellular measurements [37].

Quantitative Data on FLIM and Chromatin Condensation

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from research utilizing FLIM to probe chromatin condensation with Hoechst and DAPI dyes.

Table 1: Fluorescence Lifetime Changes of Hoechst 34580 Under Different Chromatin States in NIH/3T3 Cells [10]

| Experimental Condition | Mean Fluorescence Lifetime (ps, mean ± SD) | Interpreted Chromatin State |

|---|---|---|

| Control (Normal Medium) | 1330 ± 12 | Baseline condensation |

| Valproic Acid (VPA, 24h HDACi) | 1342 ± 12 | Global decompaction |

| Hyperosmolar (4x PBS) | 1308 ± 12 | Global compaction |

| Heterochromatin (Chromocenters in Control) | 1304 ± 15 | High local condensation |

Table 2: DAPI Fluorescence Lifetime in Fixed Human Metaphase Chromosomes [2]

| Chromosomal Region | Mean Fluorescence Lifetime (ns, mean ± SD) | Chromatin Classification |

|---|---|---|

| General Chromosome Arms | 2.80 ± 0.09 | Less condensed / Euchromatin |

| Pericentromeric (Chr 1, 16, Y) | 2.57 ± 0.06 | Constitutive heterochromatin |

| Pericentromeric (Chr 9, 15) | 2.41 ± 0.06 | Constitutive heterochromatin |

| Pericentromeric (Chr 9, specific region) | 2.21 ± 0.05 | Constitutive heterochromatin |

Table 3: Key Dyes for FLIM-based Chromatin Compaction Assays

| Reagent | Excitation | Function in Chromatin Research | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hoechst 34580 [10] | UV | Minor groove DNA binder; lifetime decreases with compaction | Cell-permeable, usable in live cells |

| DAPI [2] | UV | Minor groove DNA binder; preferential AT-binding; lifetime sensitive to condensation | Well-characterized lifetime changes in fixed samples |

| Syto 13 [10] | 488 nm | Nucleic acid stain; lifetime responds to chromatin modulation | Excitable with standard 488 nm laser, but stains RNA |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Live-Cell Chromatin Compaction Assay Using Hoechst 34580

This protocol is designed for quantifying global chromatin compaction changes in response to drug treatments or environmental stressors in living cells [10].

Materials:

- Cell Line: Adherent cells (e.g., NIH/3T3, U2OS, HeLa)

- Dye Solution: 1-5 µM Hoechst 34580 in live-cell imaging medium

- Treatments: Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors (e.g., Valproic Acid, Trichostatin A) for decompaction; Hyperosmolar medium (e.g., 4x PBS) for compaction

- Imaging Equipment: Time-Correlated Single Photon Counting (TCSPC)-FLIM system equipped with a UV laser (e.g., Ti:Sapphire laser with frequency doubler)

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation and Plating: Plate cells onto 35 mm glass-bottom dishes and culture until they reach 50-70% confluence.

- Dye Loading and Treatment:

- Replace the culture medium with the pre-warmed Hoechst 34580 dye solution.

- Incubate for 20-30 minutes at 37°C in the dark.

- Replace the dye solution with fresh imaging medium containing the desired chemical treatment (e.g., VPA for decompaction, hyperosmolar medium for compaction). Include an untreated control in parallel.

- Incubate for the required treatment duration (e.g., 24 hours for VPA).

- FLIM Data Acquisition:

- Place the dish on the pre-warmed microscope stage (37°C, 5% CO₂ if possible).

- Focus on cells with low-intensity illumination to minimize photodamage.

- Acquire FLIM images using a 60x or higher magnification oil-immersion objective.

- For TCSPC, collect photons until a sufficient number (e.g., 100-1000 photons per pixel) are accumulated for a robust lifetime fit. Ensure the detector count rate is kept low (typically <1-5% of the laser repetition rate) to avoid pile-up artifacts [10].

- Data Analysis:

- Fit the fluorescence decay curves per pixel to a mono- or bi-exponential model using specialized software (e.g., AlliGator, SPCImage, or custom algorithms) [38] [39].

- Calculate the mean fluorescence lifetime (τₘ) for each nucleus.

- Compare the average τₘ from treated populations to untreated controls. An increase in lifetime indicates chromatin decompaction, while a decrease indicates compaction [10].

Protocol 2: Mapping Chromatin Heterogeneity in Fixed Cells with DAPI

This protocol is optimized for high-resolution mapping of chromatin condensation states in fixed cell samples, such as metaphase chromosome spreads [2].

Materials:

- Sample: Fixed metaphase chromosome spreads or interphase nuclei on glass slides.

- Staining Solution: 4 µM DAPI in deionized water or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Mounting Medium: Antifade mounting medium or deionized water.

- Imaging Equipment: Multiphoton or confocal FLIM system.

Procedure:

- Sample Staining:

- Apply the 4 µM DAPI staining solution directly to the fixed chromosome spread and incubate for 5 minutes in the dark.

- Rinse the slide gently with 1x PBS to remove unbound dye.

- Mount the sample under a coverslip using an appropriate mounting medium.

- FLIM Data Acquisition:

- Use multiphoton excitation (e.g., ~700-800 nm) or a UV laser to excite DAPI.

- Collect the emission signal using a bandpass filter (e.g., 450/50 nm).

- Acquire FLIM images with high spatial sampling to resolve individual chromosomal features.

- Data Analysis:

- Generate lifetime maps and fit the data to extract lifetime values on a pixel-by-pixel basis.

- Identify structural regions of interest (e.g., chromosome arms, pericentromeric regions) based on lifetime values.

- Perform statistical analysis to compare lifetimes between different chromosomal regions, such as euchromatin and constitutive heterochromatin [2].

FLIM Assay Workflow and Interpretation Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials and Tools for FLIM Chromatin Studies

| Category / Item | Specific Example / Role | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA-Binding Dyes | Hoechst 34580, DAPI, Syto 13 | Report on chromatin state via lifetime changes; Hoechst 34580 is preferred for live-cell studies [10]. |

| Epigenetic Modulators | Trichostatin A (TSA), Valproic Acid (VPA) | HDAC inhibitors used as positive controls for inducing chromatin decompaction [36] [10]. |

| FLIM Instrumentation | TCSPC-FLIM systems, Multiphoton microscopes | Enable precise measurement of fluorescence decay kinetics; TCSPC is the gold standard [34] [39]. |

| Analysis Software | AlliGator, SPCImage, phasor approach tools | Perform lifetime decay fitting, phasor analysis, and generate quantitative lifetime maps [38] [39]. |

| Cell Lines | NIH/3T3, U2OS, HeLa, Primary cells | Model systems for studying chromatin organization; verify findings across different lines [36] [10]. |

Data Analysis and Technical Considerations

FLIM data analysis typically involves fitting the measured fluorescence decay to a mathematical model, most commonly a multi-exponential decay function: I(t) = ∑ᵢ αᵢ exp(-t/τᵢ), where αᵢ is the amplitude and τᵢ is the lifetime of the i-th component [34] [39]. The mean lifetime (τₘ = ∑ᵢ τᵢαᵢ) is then used for comparative analysis. For chromatin studies, a bi-exponential model often adequately describes the decay of dyes like Hoechst, reflecting the fluorophore population in different microenvironments [10].

Critical Technical Considerations:

- Pile-up and Counting Loss: In TCSPC-FLIM, high photon count rates can lead to "pile-up" distortion and counting losses, systematically skewing lifetime measurements. It is crucial to keep the detector count rate below ~5% of the laser repetition rate and apply appropriate correction algorithms during data processing for accurate results [10].

- Environmental Controls: For live-cell imaging, maintain strict environmental control (37°C, 5% CO₂) to ensure cell health and prevent stress-induced chromatin changes that could confound results.

- Dye Concentration: While lifetime is concentration-independent in theory, very high local dye concentrations can cause self-quenching, which may affect the lifetime. Using the minimum effective dye concentration is recommended [2].