Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Pathway Biomarkers: From Mechanisms to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of biomarkers for intrinsic and extrinsic pathway activation, crucial for researchers and drug development professionals.

Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Pathway Biomarkers: From Mechanisms to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of biomarkers for intrinsic and extrinsic pathway activation, crucial for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the fundamental definitions and biological mechanisms, explores advanced methodological approaches for their assessment, addresses common challenges in interpretation and optimization, and delivers a critical validation of their predictive power across therapeutic areas. By integrating insights from oncology, autoimmune diseases, and toxicology, this review serves as a definitive guide for the precise application of these biomarkers in personalized medicine and drug development.

Decoding the Blueprint: Core Concepts and Biological Mechanisms of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Pathways

In biological systems, the concepts of intrinsic and extrinsic pathways represent fundamental paradigms for understanding how cells process information and execute programmed responses. These pathways form the cornerstone of cellular communication, governing processes as diverse as programmed cell death (apoptosis), neuronal regeneration, and immune system regulation. The intrinsic pathway refers to signaling cascades that originate from within the cell, typically in response to internal stressors or damage signals. In contrast, the extrinsic pathway describes signaling initiated by external stimuli or ligands originating from other cells, representing intercellular communication mechanisms [1] [2].

This conceptual framework transcends specific biological contexts, providing researchers with a unified model for understanding cellular decision-making. From a therapeutic perspective, distinguishing between these pathways is crucial for drug development, as it enables targeted interventions that either modulate a cell's internal environment or manipulate extracellular signaling networks. This comparative guide examines the defining characteristics, molecular mechanisms, and experimental approaches for studying these pathways across biological systems, with particular emphasis on their implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Defining the Pathways: Core Principles and Molecular Mechanisms

The Extrinsic Pathway: Externally Triggered Signaling

The extrinsic pathway functions as a communication system between cells, where signaling is initiated by extracellular ligands binding to specific cell surface receptors. This pathway is particularly crucial in immune regulation and tissue homeostasis, allowing one cell to directly influence the fate of another [2].

The canonical extrinsic apoptosis pathway begins when death receptors of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily (TNFRSF) bind to their cognate trimeric ligands. These receptors contain a specialized protein interaction module known as a "death domain" that is approximately 80 amino acids long. Upon ligand binding, receptor oligomerization occurs, leading to the formation of a membrane-bound death-inducing signaling complex (DISC). This complex serves as a platform for recruiting and activating initiator caspases, particularly caspase-8, which then proteolytically activates downstream effector caspases such as caspase-3, committing the cell to apoptosis [1] [2].

The Intrinsic Pathway: Internally Generated Signals

The intrinsic pathway operates as a cell's internal monitoring system, activating in response to intracellular stress signals including DNA damage, oxidative stress, hypoxia, and survival factor deprivation. This pathway integrates various stress signals through sensors like the p53 protein, which acts as a critical activator of the intrinsic pathway by transcriptionally regulating pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members [1].

A pivotal event in the intrinsic apoptosis pathway is mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), which is regulated by the balance between pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins. Pro-apoptotic proteins such as BAX and BAK form pores in the mitochondrial membrane, leading to the release of cytochrome c and other pro-apoptotic factors into the cytosol. Cytochrome c then binds to Apaf-1, forming a complex called the apoptosome that activates caspase-9, which in turn activates downstream effector caspases [1] [3].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Pathways

| Characteristic | Extrinsic Pathway | Intrinsic Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Origin of Signal | Extracellular; from other cells | Intracellular; from within the cell |

| Key Initiators | Death ligands (FasL, TNF-α, TRAIL) | Cellular stress (DNA damage, oxidative stress) |

| Molecular Hubs | Death receptors (Fas, TNFR1), DISC | Mitochondria, p53, Bcl-2 family proteins |

| Key Adaptors | FADD, TRADD | Apaf-1, cytochrome c |

| Initiator Caspases | Caspase-8, Caspase-10 | Caspase-9 |

| Regulatory Proteins | FLIP, cIAPs | Bcl-2 family, IAPs, SMAC/Diablo |

| Primary Functions | Immune regulation, tissue homeostasis | Response to cellular damage, development |

Comparative Analysis: Key Biological Contexts

Apoptosis: The Paradigm System

The distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic pathways is most clearly defined in apoptosis, where both pathways converge on caspase activation but differ fundamentally in their initiation mechanisms. The extrinsic apoptotic pathway begins when death ligands such as Fas ligand (FasL) or TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) bind to their cognate receptors, rapidly triggering caspase activation within seconds of ligand binding [1].

In contrast, the intrinsic apoptotic pathway (also called the mitochondrial pathway) responds to internal damage cues through mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, leading to cytochrome c release and apoptosome formation. This pathway involves a more delayed response as it requires transcriptional and post-translational regulation of Bcl-2 family proteins [1] [3].

Notably, cross-talk exists between these pathways. For example, activated caspase-8 in the extrinsic pathway can cleave the Bcl-2 family protein BID, generating truncated BID (tBID) that translocates to mitochondria and amplifies the apoptotic signal through the intrinsic pathway [1] [4].

Neuronal Development and Injury Responses

In neuronal systems, intrinsic and extrinsic pathways exhibit distinct roles in development, plasticity, and response to injury. Research using mutant mice has revealed that in sympathetic neurons, apoptosis induced by trophic factor deprivation primarily follows the intrinsic pathway, depending on BAX translocation and cytochrome c release despite the expression of both intrinsic and extrinsic pathway components [4].

Recent studies on spinal cord injury recovery demonstrate how modulating both pathways simultaneously can enhance therapeutic outcomes. Deletion of RhoA (an extrinsic pathway modulator responsive to extracellular inhibitory signals) combined with deletion of Pten (an intrinsic pathway inhibitor of neuronal growth) in corticospinal neurons, coupled with neuronal activation, promoted significantly greater axonal growth and functional recovery than either intervention alone [5]. This highlights the therapeutic potential of coordinated targeting of both pathways.

Immune Regulation and Disease Pathogenesis

In immunology, the extrinsic pathway plays a crucial role in immune surveillance, with natural killer (NK) cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) using death receptor ligands to eliminate virally infected or transformed cells [2]. Meanwhile, the intrinsic pathway regulates immune cell homeostasis, controlling the contraction phase of immune responses after pathogen clearance.

In autoimmune disorders like systemic sclerosis, recent single-cell RNA-sequencing analyses have revealed that disease severity involves complex rewiring of both cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic signaling networks across multiple cell types, including fibroblasts, myeloid cells, and keratinocytes. This suggests that both autonomous cellular signaling and intercellular communication contribute to disease progression [6].

Table 2: Pathway Involvement Across Biological Processes

| Biological Process | Dominant Pathway | Key Molecular Players | Cellular Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Developmental Apoptosis | Primarily Intrinsic | Bcl-2 family, Caspase-9 | Sculpting tissues, eliminating excess cells |

| Immune-Mediated Cell Killing | Primarily Extrinsic | Death receptors, Caspase-8 | Elimination of infected or transformed cells |

| Neuronal Plasticity/Regeneration | Both | RhoA (extrinsic), Pten (intrinsic) | Axonal growth, synaptic rewiring |

| Stress-Induced Apoptosis | Primarily Intrinsic | p53, BAX, Cytochrome c | Elimination of damaged cells |

| Autoimmune Pathogenesis | Both | Cell-type specific biomarkers | Inflammation, fibrosis, tissue damage |

Experimental Approaches: Methodologies and Reagents

Pathway Analysis Techniques

Investigating intrinsic and extrinsic pathways requires specialized methodologies that can distinguish between these overlapping but distinct signaling cascades. Key experimental approaches include:

Genetic Manipulation: Studies using knockout mice, such as Bax⁻/⁻, Bak⁻/⁻, Bim⁻/⁻, Bid⁻/⁻, and Bad⁻/⁻ neurons, have been instrumental in defining functional redundancies and specific roles of Bcl-2 family members in intrinsic pathway regulation [4]. Similarly, analysis of lpr and gld mice, which have mutations in Fas and FasL respectively, has helped elucidate extrinsic pathway components.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: Advanced computational approaches like LASSO-based predictive machine learning applied to single-cell RNA-sequencing data can identify predictive biomarkers of disease severity across cell types, revealing both cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic signaling networks [6].

Neuronal Stimulation and Circuit Mapping: Combining genetic modifications with chemogenetic neuronal stimulation (e.g., DREADD technology) allows researchers to test the functional outcomes of pathway manipulations. This approach demonstrated that pairing RhoA/Pten deletion with chemogenetic stimulation enhanced presynaptic bouton formation and motor recovery after spinal cord injury [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Pathway Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Modulators | AAV8-fDIO-Cre, AAVretro-DIO-hM3Dq-mCherry | Cell-type specific gene deletion, chemogenetic neuronal stimulation |

| Pathway Activators/Inhibitors | Death ligands (FasL, TRAIL), Bcl-2 inhibitors, Caspase inhibitors | Selective pathway activation or inhibition |

| Detection Antibodies | Phosphospecific antibodies, Bcl-2 family antibodies, Death receptor antibodies | Protein localization, post-translational modification analysis |

| Animal Models | Bax⁻/⁻, Bak⁻/⁻, Bim⁻/⁻, Bid⁻/⁻, lpr (Fas mutant), gld (FasL mutant) mice | Defining pathway components in physiological contexts |

| Computational Tools | LASSO-based predictive modeling, correlation network analyses | Identification of predictive biomarkers and signaling networks |

Signaling Pathway Visualizations

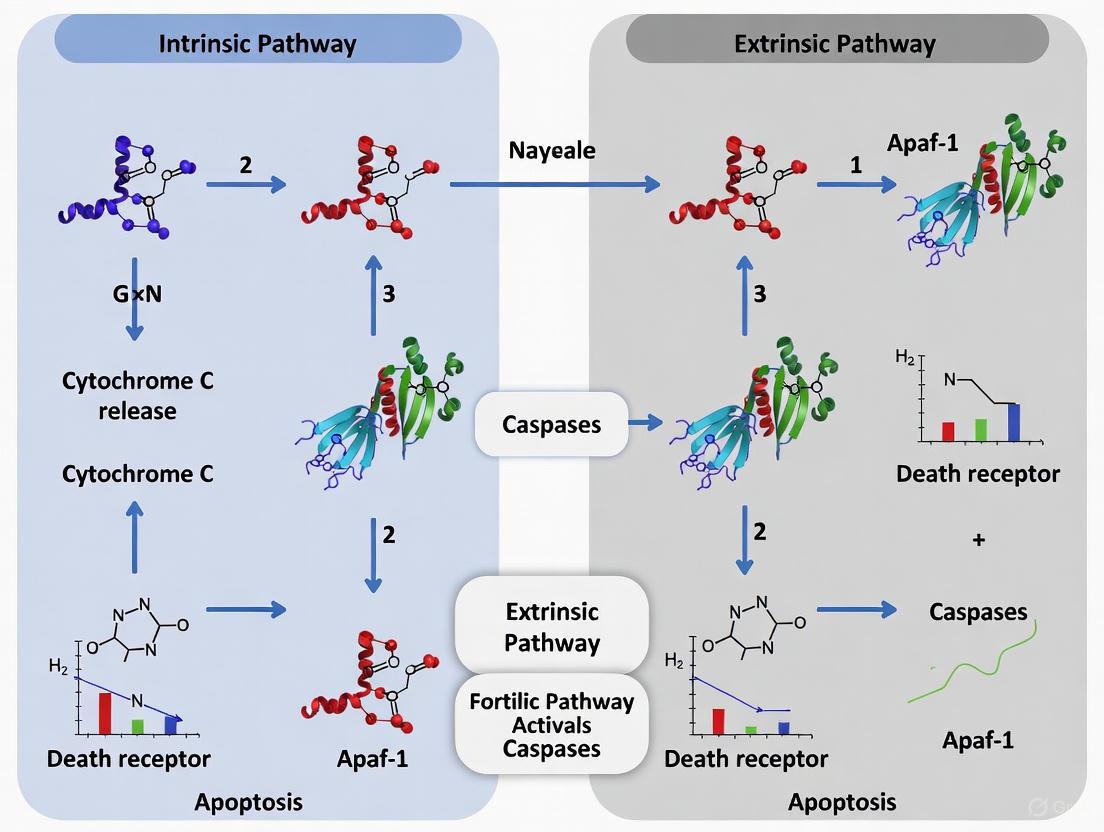

Diagram 1: Intrinsic and Extrinsic Apoptosis Signaling Pathways. The extrinsic pathway (top) initiates from extracellular death ligands binding to cell surface receptors, while the intrinsic pathway (bottom) begins with intracellular stress signals. Both pathways converge on caspase-3/7 activation, with cross-talk occurring through BID cleavage.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Pathway Analysis. This workflow illustrates the integrated approach combining genetic manipulation, stimulation paradigms, single-cell sequencing, computational analysis, and functional validation to delineate intrinsic and extrinsic pathway contributions.

The conceptual framework distinguishing intrinsic and extrinsic pathways provides a powerful paradigm for understanding cellular communication and fate decisions across biological systems. Rather than existing as isolated entities, these pathways exhibit complex interactions and cross-talk that integrate internal cellular states with external environmental cues. For researchers and drug development professionals, this distinction offers strategic opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

Future research directions will likely focus on developing more sophisticated tools for selectively modulating these pathways, particularly in a cell-type-specific manner. The integration of single-cell technologies with computational approaches will continue to reveal novel biomarkers and signaling networks that operate across intrinsic and extrinsic dimensions. Furthermore, combinatorial approaches that simultaneously target both pathways—as demonstrated in spinal cord injury models—hold significant promise for enhancing therapeutic efficacy in complex diseases.

As our understanding of these fundamental biological pathways deepens, so too does our ability to precisely manipulate cellular behavior for therapeutic benefit, ushering in a new era of targeted interventions for cancer, neurological disorders, autoimmune conditions, and regenerative medicine applications.

Programmed cell death, or apoptosis, is a fundamental process critical for tissue homeostasis, embryonic development, and the removal of damaged or unwanted cells. In mammalian systems, apoptosis proceeds primarily through two evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways: the mitochondrial (intrinsic) pathway and the death receptor (extrinsic) pathway [7] [8]. While these pathways are initiated by distinct stimuli and involve different upstream components, they ultimately converge to activate a cascade of proteases that systematically dismantle the cell. Disruption of either pathway can lead to pathological conditions; insufficient apoptosis contributes to cancer progression and autoimmune diseases, while excessive apoptosis is implicated in neurodegenerative disorders and stroke [7] [9]. This guide provides a detailed comparative analysis of the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways, focusing on key biomarkers, experimental methodologies, and the crucial cross-talk that integrates these systems. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes current understanding to support targeted investigations into apoptotic signaling cascades.

Pathway Comparison: Core Components and Mechanisms

The intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis pathways, while functionally convergent, are characterized by unique initiators, regulators, and execution mechanisms. The table below provides a systematic comparison of their core components.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of the Intrinsic and Extrinsic Apoptosis Pathways

| Feature | Mitochondrial (Intrinsic) Pathway | Death Receptor (Extrinsic) Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Initiating Stimuli | Internal stress: DNA damage, hypoxia, oxidative stress, cytokine deprivation, cytotoxic agents [10] [1] | External ligands: FasL, TNF-α, TRAIL binding to cell surface death receptors [11] [1] |

| Key Initiators | p53, Bcl-2 family proteins (BH3-only sensors, Bax/Bak) [9] [1] | Death Receptors (Fas, TNFR1, DR4/5), FADD, caspase-8 [11] [1] |

| Activation Complex | Apoptosome (Cytochrome c + Apaf-1 + caspase-9) [7] [1] | DISC (Death-Inducing Signaling Complex) [11] [1] |

| Key Initiator Caspase | Caspase-9 [7] [9] | Caspase-8 [11] [9] |

| Regulatory Proteins | Bcl-2, Bcl-xL (anti-apoptotic); Bax, Bak, Bid, Bad, Bim, Puma (pro-apoptotic) [10] [9] [1] | FLIP (inhibits caspase-8), cIAPs (Inhibitor of Apoptosis Proteins) [11] [1] |

| Mitochondrial Involvement | Central event: MOMP, release of cytochrome c, Smac/Diablo [7] [1] | Optional amplification: via caspase-8-mediated cleavage of Bid to tBid [11] [8] |

| Primary Function | Elimination of damaged or stressed cells [1] | Immune regulation, deletion of infected or abnormal cells [7] [1] |

The intrinsic pathway functions as a sensor of internal cellular well-being. Stress signals such as DNA damage or growth factor withdrawal are monitored by sensors like p53, which transcriptionally activates pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members like Bax, Puma, and Noxa [1]. The critical execution point is Mitochondrial Outer Membrane Permeabilization (MOMP), which is controlled by the balanced interactions of the Bcl-2 protein family. Anti-apoptotic members (e.g., Bcl-2, Bcl-xL) preserve membrane integrity, while activated pro-apoptotic effectors Bax and Bak form pores, leading to the release of cytochrome c and other apoptogenic factors [7] [9]. Cytochrome c in the cytosol binds to Apaf-1, triggering the formation of the apoptosome and the activation of caspase-9, which then initiates the downstream caspase cascade [7] [1].

In contrast, the extrinsic pathway is activated from outside the cell by ligand-mediated engagement of death receptors. Upon binding their cognate ligands (e.g., FasL to Fas), the receptors oligomerize and recruit the adaptor protein FADD and the initiator procaspase-8 to form the Death-Inducing Signaling Complex (DISC) [11] [1]. Within the DISC, caspase-8 is activated through proximity-induced autocatalysis. In some cell types (classified as Type I), active caspase-8 is sufficient to directly cleave and activate effector caspases like caspase-3. In others (Type II cells), the signal is amplified through the intrinsic pathway via caspase-8-mediated cleavage of the BH3-only protein Bid. Truncated Bid (tBid) translocates to mitochondria, promoting MOMP and engaging the intrinsic amplification loop [7] [11] [8].

Experimental Data and Biomarker Analysis

Empirical data from various models highlight the distinct yet interconnected nature of these pathways. The following table summarizes key biomarkers and representative experimental findings.

Table 2: Key Apoptotic Biomarkers and Experimental Evidence

| Biomarker / Assay | Role/Function | Experimental Context & Findings |

|---|---|---|

| BID | BH3-only protein; critical linker (crosstalk) cleaved by caspase-8 to form tBid, which activates mitochondrial pathway [11] [8] | ICH (Intracerebral Hemorrhage) Model: Identified as a key biomarker in apoptosis post-ICH. Validation in a rat model showed significant involvement, regulated by miR-1225-3p [12]. |

| Caspase-8 | Initiator caspase in extrinsic pathway; activated at the DISC [11] [1] | Daunorubicin Treatment (Leukemia): Activation confirmed in CCRF-CEM and MOLT-4 T-lymphoblastic leukemia cells, indicating engagement of the extrinsic pathway [10]. |

| Caspase-9 | Initiator caspase in intrinsic pathway; activated by the apoptosome [7] [1] | Daunorubicin Treatment (Leukemia): Activation observed in CCRF-CEM and MOLT-4 cells, indicating concurrent intrinsic pathway activation [10]. |

| Cytochrome c Release | Hallmark of MOMP; triggers apoptosome formation [7] [1] | Direct Irradiation: Upstream of caspase-9 activation, a definitive marker of intrinsic pathway engagement following direct cellular damage [13]. |

| Bax/Bak | Pro-apoptotic executioner proteins; mediate MOMP [9] [1] | Ionizing Radiation: Pro-apoptotic Bax was up-regulated in response to direct irradiation, promoting mitochondrial dysfunction [13]. |

| Phosphatidylserine Externalization | "Eat-me" signal on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane [9] | Annexin V Assay: Used to detect early apoptosis in daunorubicin-treated leukemia cells and camptothecin-treated Jurkat cells [10] [9]. |

| DNA Fragmentation | Late-stage apoptotic event; result of CAD nuclease activation [1] | TUNEL Assay: Effectively detected apoptosis in a developing mouse embryo (E14.5) and in a rat ICH model [12] [9]. |

Case Study: Daunorubicin-Induced Apoptosis in Leukemia Cells

Research on daunorubicin-treated leukemia cell lines provides a clear example of how both pathways can be engaged with cell-type-specific variations. In T-lymphoblastic leukemia cells (CCRF-CEM and MOLT-4), treatment with 10 μM daunorubicin for 4 hours followed by a recovery period induced apoptosis through both intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. Evidence included the activation of both caspase-8 and caspase-9, along with changes in mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) [10]. In contrast, under the same conditions, SUP-B15 (B-lymphoblastic leukaemia) cells exhibited signs of apoptosis but without a loss of Δψm, suggesting cell death was primarily driven by the extrinsic pathway, independent of mitochondrial amplification [10]. This underscores that the requirement for mitochondrial involvement in death receptor signaling is cell-type-dependent.

Methodologies for Apoptosis Detection

Accurate assessment of apoptosis requires a multi-parametric approach to distinguish it from other forms of cell death and to identify the initiating pathway.

- Annexin V/Propidium Iodide (PI) Staining: This assay detects the externalization of phosphatidylserine, an early event in apoptosis. Annexin V binds to phosphatidylserine, while PI is a vital dye that stains cells with compromised membranes (necrotic cells or late-stage apoptotic cells). Live cells are Annexin V-/PI-; early apoptotic cells are Annexin V+/PI-; and late apoptotic/necrotic cells are Annexin V+/PI+ [10] [9].

- Caspase Activity Measurement: Activation of specific initiator caspases can help delineate the pathway involved. This can be done using fluorogenic substrate assays or flow cytometry with pancaspase inhibitors like Apostat [10]. Selective caspase-8 or caspase-9 inhibitors can further define the contribution of each pathway.

- Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (Δψm) Assay: The loss of Δψm is an early event in the intrinsic pathway. Fluorescent dyes like DiOC₆ or TMRE accumulate in active mitochondria based on membrane potential. A decrease in fluorescence signal indicates mitochondrial depolarization, a key step in MOMP [10] [9].

- TUNEL Assay: The TUNEL (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP Nick End Labeling) assay detects DNA fragmentation, a hallmark of late-stage apoptosis. It labels the 3'-OH ends of fragmented DNA, which can be visualized by fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry [12] [9].

- Western Blot Analysis: This technique is crucial for detecting the cleavage and activation of key apoptotic proteins, such as caspases (e.g., cleavage of procaspase-3 to active caspase-3), and Bid (cleavage to tBid), as well as changes in the expression levels of Bcl-2 family proteins [12] [10].

- Immunofluorescence (IF): IF allows for the subcellular localization of proteins. It can be used to visualize cytochrome c release from mitochondria, the translocation of Bax to mitochondria, or the cleavage and activation of caspases, providing spatial information about pathway activation [12] [9].

Pathway Crosstalk and Integration

The intrinsic and extrinsic pathways are not isolated; significant cross-talk exists, primarily mediated by the BH3-only protein Bid [7] [8]. As detailed in Figure 1, in Type II cells, activation of the death receptor pathway leads to caspase-8 activation. Caspase-8 then cleaves Bid into its active truncated form, tBid. tBid translocates to the mitochondria, where it promotes MOMP by activating Bax and Bak or antagonizing anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins, thereby engaging the intrinsic pathway to amplify the apoptotic signal [11] [8]. This cross-talk ensures a robust and irreversible commitment to cell death when signals from either pathway are insufficient on their own.

The following DOT code defines a diagram illustrating the crosstalk between the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic pathways.

Figure 1: Crosstalk between Apoptotic Pathways. The extrinsic pathway can amplify the death signal via caspase-8-mediated cleavage of Bid to tBid, which engages the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway. MOMP: Mitochondrial Outer Membrane Permeabilization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table lists essential reagents and kits for studying apoptosis, drawing from methodologies cited in the research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Apoptosis Investigation

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function / Target | Application & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Annexin V-Based Kits | Binds to externalized Phosphatidylserine | Flow cytometry or IF detection of early apoptosis. Must be used with a viability dye (e.g., PI) to distinguish from late apoptosis/necrosis [10] [9]. |

| TUNEL Assay Kit | Labels 3'-OH ends of fragmented DNA | Detection of late-stage apoptosis via IF, IHC, or flow cytometry. Not specific to apoptosis; requires morphological confirmation [12] [9]. |

| Caspase Activity Assays | Measure activation of specific caspases (e.g., 3, 8, 9) | Use fluorogenic substrates or inhibitors (e.g., Apostat). Differentiates pathway involvement (caspase-8 for extrinsic, caspase-9 for intrinsic) [10]. |

| Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Dyes (e.g., DiOC₆, TMRE, JC-1) | Accumulate in polarized mitochondria | Flow cytometry or microscopy to detect loss of Δψm, an early event in the intrinsic pathway [10] [9]. |

| Antibodies for Western Blot/IF | Target cleaved/activated proteins (e.g., Cleaved Caspase-3, Cleaved PARP, tBid) | Confirms protein cleavage as a marker of activation. IF allows subcellular localization (e.g., cytochrome c release) [12] [9]. |

| Bcl-2 Family Antibody Sampler Kits | Detect pro- and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members | Monitor expression changes and post-translational modifications of key regulators of the intrinsic pathway [9]. |

| Chemical Inducers/Inhibitors | Activate or inhibit specific pathway components | e.g., Caspase-8 inhibitor Z-IETD-FMK; Bax/Bak activator ABT-737. Useful for dissecting pathway contributions. |

The following DOT code defines a diagram outlining a typical experimental workflow for differentiating apoptotic pathways.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Pathway Differentiation. A decision-tree approach to delineate the primary apoptotic pathway engaged, utilizing sequential assays from early to late markers.

Cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic factors represent two fundamental categories of biological signals that coordinate gene regulation in development and disease. Cell-intrinsic factors originate from within the cell, including genetic programs, transcription factors, and metabolic states, while cell-extrinsic factors comprise external signals such as circulating hormones, cytokines, and cell-cell contact mediators. Understanding the interplay between these factors provides critical insights into disease mechanisms and therapeutic development. This guide compares experimental approaches for studying these regulatory systems, with particular focus on apoptosis and blood coagulation as paradigmatic examples of intrinsic and extrinsic pathway activation.

Defining Intrinsic and Extrinsic Pathways: Core Concepts and Biological Systems

Apoptosis: A Paradigm of Programmed Cell Death

The apoptotic pathway demonstrates the fundamental distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic activation mechanisms. Both pathways culminate in caspase activation and controlled cellular dismantling but initiate through distinct mechanisms and biomarkers [9].

Intrinsic Pathway (Mitochondrial Pathway): Triggered by internal cellular damage or stress, this pathway involves mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), cytochrome c release, and caspase-9 activation. Key regulators include BCL-2 family proteins, which contain conserved BCL-2 homology (BH) domains that determine pro- or anti-apoptotic function [14].

Extrinsic Pathway (Death Receptor Pathway): Initiated by extracellular death ligands (TNF-α, FasL) binding to cell surface receptors, leading to formation of the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) and caspase-8 activation [9].

Coagulation: Proteolytic Cascade in Blood Clotting

The coagulation system similarly operates through distinct intrinsic and extrinsic pathways that converge on common effectors [15].

Intrinsic Coagulation Pathway: Activated by exposed endothelial collagen and involving factors XII, XI, IX, and VIII. Assessed clinically via partial thromboplastin time (PTT) [15] [16].

Extrinsic Coagulation Pathway: Triggered by external trauma and tissue factor release, involving factor VII. Measured clinically via prothrombin time (PT) [15] [17].

Comparative Analysis of Pathway Biomarkers

Table 1: Key Biomarkers in Intrinsic and Extrinsic Apoptotic Pathways

| Parameter | Intrinsic Apoptosis | Extrinsic Apoptosis |

|---|---|---|

| Initiating Stimuli | Cellular stress, DNA damage, oxidative stress | Death ligands (FasL, TNF-α, TRAIL) |

| Membrane Receptors | Not receptor-mediated | Death receptors (Fas, TNFR, TRAIL-R) |

| Adaptor Molecules | Apaf-1 | FADD, TRADD |

| Key Initiator Caspases | Caspase-9 | Caspase-8, Caspase-10 |

| Regulatory Proteins | BCL-2 family (Bax, Bak, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL) | FADD, c-FLIP |

| Mitochondrial Involvement | Central (MOMP, cytochrome c release) | Secondary (via Bid cleavage) |

| Biomarker Detection Methods | Cytochrome c release, Bax/Bak activation, caspase-9 cleavage | DISC formation, caspase-8 activation, death ligand levels |

Table 2: Key Biomarkers in Intrinsic and Extrinsic Coagulation Pathways

| Parameter | Intrinsic Coagulation | Extrinsic Coagulation |

|---|---|---|

| Initiating Stimuli | Exposed endothelial collagen, negatively charged surfaces | Tissue factor release from external injury |

| Key Factors | XII, XI, IX, VIII | VII, III (tissue factor) |

| Activation Time | Longer cascade | Shorter, more rapid activation |

| Clinical Tests | Partial Thromboplastin Time (PTT) | Prothrombin Time (PT) |

| Diagnostic Applications | Hemophilia A/B diagnosis, heparin monitoring | Liver disease, warfarin monitoring, vitamin K deficiency |

| Convergence Point | Factor X activation | Factor X activation |

Experimental Protocols for Pathway Analysis

Protocol 1: Thrombin Generation Measurement in Whole Blood

This protocol assesses coagulation capacity in mouse whole blood, adaptable for human samples [18].

Sample Collection:

- Collect blood into 3.2% trisodium citrate (9:1 blood:citrate ratio)

- Discard first drop to avoid contamination

- Process samples within 4 hours of collection

Reaction Setup:

- Use 96-well round-bottom plates

- Final reaction mixture: 65μL per well

- Add 10μL citrated whole blood to wells

- Mix with 23μL stimulator (kaolin, ellagic acid, or polyphosphate for intrinsic pathway activation)

- Add 20μL fluorogenic substrate mixture (Z-Gly-Gly-Arg-AMC)

- Include 12μL calcium chloride to reverse citrate anticoagulation

Measurement Parameters:

- Lag time: Duration until thrombin generation initiates

- Time to peak: Time until maximum thrombin generation

- Peak thrombin: Maximum thrombin concentration achieved

- Endogenous thrombin potential (ETP): Total thrombin generated over time

Validation Controls:

- Include FXII-deficient blood (F12-/-) for specificity confirmation

- Use direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) as inhibition controls

- Employ specific inhibitors (rHA-Infestin-4 for FXIIa) to verify mechanism

Protocol 2: Apoptosis Pathway Analysis via Caspase Activation

This methodology distinguishes intrinsic versus extrinsic apoptosis activation [9].

Cell Stimulation:

- For extrinsic pathway: Treat cells with death ligands (FasL, TNF-α, TRAIL) at appropriate concentrations (typically 10-100 ng/mL) for 2-24 hours

- For intrinsic pathway: Indce with cellular stressors (staurosporine 0.1-1 μM, UV irradiation, or chemotherapeutic agents)

Membrane Changes Detection (Early Apoptosis):

- Use Annexin V-FITC staining (1:100 dilution in binding buffer)

- Counterstain with propidium iodide (1 μg/mL) to distinguish early vs. late apoptosis

- Analyze by flow cytometry within 1 hour of staining

- Critical Note: Annexin V alone cannot distinguish apoptosis from other cell death forms; always include viability markers

Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assessment:

- Stain cells with TMRE (tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester; 100-500 nM)

- Incubate for 15-30 minutes at 37°C

- Analyze fluorescence decrease indicating membrane potential loss

- Include CCCP (10-50 μM) as positive control for depolarization

Caspase Activity Measurement:

- Use fluorogenic caspase substrates (DEVD-AFC for caspase-3, IETD-AFC for caspase-8, LEHD-AFC for caspase-9)

- Measure cleavage product fluorescence hourly for 4-8 hours

- Include caspase inhibitors (Z-VAD-FMK, 20 μM) as specificity controls

Western Blot Analysis:

- Probe for cleaved caspases (anti-cleaved caspase-3, -8, -9 antibodies)

- Detect BCL-2 family members (Bax, Bak, Bid cleavage)

- Assess cytochrome c release from mitochondrial fractions

Pathway Signaling Diagrams

Figure 1: Intrinsic and Extrinsic Apoptosis Pathway Signaling. The intrinsic pathway (red) initiates from internal cellular stress, while the extrinsic pathway (blue) begins with extracellular death ligands. Cross-talk occurs via Bid cleavage (yellow).

Figure 2: Intrinsic and Extrinsic Coagulation Pathway Signaling. Both pathways converge at Factor X activation in the common pathway (green), culminating in fibrin clot formation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Intrinsic and Extrinsic Pathway Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Activators | Kaolin, ellagic acid, polyphosphate [18] | Intrinsic coagulation studies | Contact activation of Factor XII |

| Tissue factor, recombinant Factor VIIa [15] | Extrinsic coagulation studies | Initiate tissue factor pathway | |

| Staurosporine, UV irradiation, chemotherapeutics [9] | Intrinsic apoptosis induction | Cellular stress induction | |

| Recombinant death ligands (FasL, TNF-α, TRAIL) [9] | Extrinsic apoptosis studies | Death receptor activation | |

| Inhibitors & Modulators | rHA-Infestin-4 [18] | FXIIa-specific inhibition | Contact pathway blockade |

| Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) [18] | Coagulation pathway inhibition | Thrombin/FXa inhibition | |

| Z-VAD-FMK (pan-caspase inhibitor) [9] | Apoptosis inhibition | Caspase activity blockade | |

| Venetoclax (BCL-2 inhibitor) [14] | Intrinsic apoptosis promotion | BH3 mimetic, disrupts BCL-2 interactions | |

| Detection Reagents | Fluorogenic substrates (Z-G-G-R-AMC) [18] | Thrombin generation assays | Thrombin activity measurement |

| Annexin V conjugates [9] | Early apoptosis detection | Phosphatidylserine exposure | |

| TMRE, JC-1 dyes [9] | Mitochondrial membrane potential | MOMP detection in intrinsic apoptosis | |

| Anti-cleaved caspase antibodies [9] | Apoptosis pathway mapping | Specific caspase activation | |

| Cell Models | FXII-deficient (F12-/-) blood [18] | Coagulation pathway studies | Intrinsic pathway specificity |

| Primary cells vs. cell lines | Pathway mechanism validation | Physiological relevance assessment |

Discussion: Research Applications and Therapeutic Implications

Disease-Specific Pathway Alterations

The differential activation of intrinsic and extrinsic pathways has significant disease implications. In depression research, the extrinsic coagulation pathway demonstrates altered activity, with studies identifying significantly upregulated fibrinogen chains (FGA, FGB, FGG) and downregulated Factor VII in patient plasma [19]. These findings suggest cross-talk between coagulation and inflammation in neuropsychiatric disorders.

Suicidal behavior in major depressive disorder shows distinct extrinsic coagulation pathway activation, with altered inflammatory and coagulatory protein profiles in attempters versus non-attempters [20]. This pattern reveals a proinflammatory and prothrombotic phenotype associated with specific behavioral manifestations.

Network Biomarkers in Pathway Analysis

Emerging approaches integrate multiple biomarkers into network-based analyses. Network biomarkers consider protein-protein or gene-gene interactions rather than individual molecules, while dynamic network biomarkers (DNBs) monitor these interactions across disease progression stages [21]. This approach is particularly valuable for:

- Identifying pre-disease states through correlation and fluctuation patterns

- Understanding therapeutic mechanisms via network perturbation analysis

- Developing pathway-specific diagnostics with improved sensitivity/specificity

Therapeutic Targeting Strategies

Pathway-specific targeting requires distinct approaches:

Intrinsic Pathway Targeting: BCL-2 inhibition with venetoclax in hematologic malignancies demonstrates selective killing through intrinsic apoptosis activation [14]. Similarly, FXII-targeting agents show antithrombotic potential without bleeding risk in coagulation [18].

Extrinsic Pathway Targeting: Death receptor agonists (e.g., TRAIL receptor agonists) and extrinsic coagulation inhibitors (e.g., anti-tissue factor antibodies) provide extrinsic pathway modulation.

The integration of intrinsic and extrinsic pathway biomarkers enables comprehensive disease mapping and therapeutic development across multiple pathological conditions.

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is a fundamental process essential for maintaining tissue homeostasis and eliminating damaged or unnecessary cells in multicellular organisms [14]. The intrinsic apoptotic pathway, also known as the mitochondrial pathway, represents one of the two main routes of apoptosis initiation and is centrally controlled by the B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) protein family [22] [23]. This pathway is characterized by mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), which serves as a critical commitment point to cellular destruction [23]. Upon MOMP, several pro-apoptotic proteins are released from the mitochondrial intermembrane space into the cytosol, including cytochrome c, second mitochondria-derived activator of caspases (SMAC, also known as DIABLO), apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF), and endonuclease G [24] [25]. These proteins orchestrate the systematic dismantling of the cell through caspase-dependent and independent mechanisms.

The intrinsic pathway is primarily activated in response to intracellular stressors, including DNA damage, growth factor deprivation, oxidative stress, and oncogene activation [23] [26]. Given its crucial role in maintaining cellular integrity and eliminating compromised cells, dysregulation of this pathway is a hallmark of cancer and other diseases [22] [14]. Cancer cells often develop mechanisms to evade apoptosis, frequently through overexpression of anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family members or mutations in key components of the pathway [22]. Consequently, biomarkers of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway have emerged as critical tools for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic targeting. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of three central biomarker categories: cytochrome c, SMAC/Diablo, and BCL-2 family proteins, focusing on their molecular functions, experimental detection, and clinical relevance.

Molecular Functions and Mechanisms

BCL-2 Family Proteins: The Regulators of MOMP

The BCL-2 protein family serves as the central regulatory unit of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, governing the critical decision point of MOMP [22] [23]. This family consists of three structurally and functionally distinct subgroups classified based on their BCL-2 homology (BH) domains and their effects on apoptosis:

- Anti-apoptotic proteins (BCL-2, BCL-XL, BCL-W, MCL-1, A1/BFL-1) contain four BH domains (BH1-BH4) and promote cell survival by inhibiting the activation of pro-apoptotic effectors [22] [14]. These proteins function by sequestering pro-apoptotic family members, thereby maintaining mitochondrial membrane integrity.

- Pro-apoptotic pore-formers (BAX, BAK, BOK) multi-domain proteins that, when activated, oligomerize to form pores in the mitochondrial outer membrane, leading to MOMP [22] [23].

- Pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins (BIM, BID, PUMA, NOXA, BAD, BMF, BIK, HRK) function as sensitizers or activators that initiate the apoptotic cascade by neutralizing anti-apoptotic proteins or directly activating BAX and BAK [22] [14].

The balance between these competing factions determines cellular fate. In healthy cells, anti-apoptotic members maintain mitochondrial integrity by binding and neutralizing activated pro-apoptotic proteins. During apoptosis induction, BH3-only proteins are activated transcriptionally and/or post-translationally, tipping the balance toward MOMP [22] [23]. The "primed for death" state describes cancer cells that overexpress anti-apoptotic proteins but remain highly susceptible to BH3 mimetics because they are poised to undergo apoptosis once these anti-apoptotic proteins are inhibited [22].

Cytochrome c: The Caspase Activator

Cytochrome c is a well-studied mitochondrial protein with a dual role in cellular metabolism and apoptosis [24] [25]. In healthy cells, it functions as an essential component of the electron transport chain, localized between the inner and outer mitochondrial membranes where it transfers electrons from complex III to complex IV [24]. Following MOMP, cytochrome c is released into the cytosol, where it undergoes a profound functional switch from metabolic regulator to apoptotic activator [24] [26].

In the cytosol, cytochrome c binds to apoptotic protease-activating factor-1 (APAF-1), triggering a conformational change that enables APAF-1 to oligomerize into a wheel-like signaling complex known as the apoptosome [24]. The apoptosome then recruits and activates procaspase-9 through caspase recruitment domains (CARD), initiating the caspase cascade that leads to cellular dismantling [25]. Activated caspase-9 cleaves and activates downstream effector caspases (caspase-3 and -7), which execute apoptosis by proteolytically degrading hundreds of cellular substrates [24] [25].

SMAC/Diablo: The IAP Antagonist

SMAC (second mitochondria-derived activator of caspases), also known as DIABLO (direct IAP binding protein with low pI), is a crucial mitochondrial protein that promotes apoptosis by counteracting inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) [27] [25]. This 239-amino acid protein is synthesized as a precursor with an N-terminal mitochondrial targeting sequence that directs it to the mitochondrial intermembrane space [27]. Upon mitochondrial import, the N-terminal 55 residues are cleaved, generating the mature, functional protein [27] [25].

The mature form of SMAC/Diablo exists as an arch-shaped homodimer that exposes an N-terminal tetrapeptide motif (Ala-Val-Pro-Ile, or AVPI) essential for its function [27]. Following MOMP, SMAC/Diablo is released into the cytosol where its AVPI motif binds to baculoviral IAP repeat (BIR) domains in IAP family proteins, particularly XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2 [27] [25]. This interaction neutralizes IAP-mediated caspase inhibition, thereby permitting apoptosis progression. Specifically, SMAC/Diablo binding displaces caspases from XIAP's BIR2 and BIR3 domains, relieving the suppression of caspase-3, -7, and -9 activity [27] [25]. Beyond this primary function, SMAC/Diablo can also promote the ubiquitin-mediated degradation of IAPs through its RING domain and may have IAP-independent roles in apoptosis [27].

Table 1: Comparative Functions of Core Intrinsic Pathway Biomarkers

| Biomarker | Subcellular Location (Inactive) | Activation Mechanism | Primary Molecular Function | Key Interacting Partners |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCL-2 Family | Mitochondrial membrane, cytosol | BH3-only protein activation | Regulation of MOMP | Other BCL-2 members, mitochondrial membranes |

| Cytochrome c | Mitochondrial intermembrane space | Release after MOMP | Caspase activation via apoptosome formation | APAF-1, caspase-9, cardiolipin |

| SMAC/Diablo | Mitochondrial intermembrane space | Release after MOMP, N-terminal processing | IAP neutralization | XIAP, cIAP1, cIAP2 |

Experimental Detection and Methodologies

Immunohistochemistry and Tissue Microarray Analysis

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) represents a widely employed technique for detecting intrinsic pathway biomarkers in tissue specimens, allowing for simultaneous protein localization and morphological assessment. A comprehensive study analyzing gastric adenocarcinoma tissues demonstrated the utility of IHC combined with tissue microarray (TMA) technology for evaluating DIABLO, AIF, cytochrome c, and cleaved caspase-3 expression [28]. The experimental protocol involved:

TMA Construction and Staining Protocol:

- Tissue sections (4 μm) were cut from paraffin-embedded gastric adenocarcinoma and normal adjacent mucosa blocks from 87 patients [28].

- Cylindrical cores (1 mm diameter) were extracted from donor blocks and transferred to a recipient TMA block using specialized equipment [28].

- Sections (3 μm) were mounted on coated slides, deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated through graded ethanol [28].

- Antigen retrieval was performed by heating slides in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 30 minutes [28].

- Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 20 minutes [28].

- Primary antibodies were applied and incubated overnight at 4°C: DIABLO (1:200), AIF (1:400), cytochrome c (1:500), cleaved caspase-3 (1:100) [28].

- Detection was performed using biotinylated link universal and streptavidin-HRP with DAB as the chromogen, followed by counterstaining with Harris hematoxylin [28].

Scoring and Interpretation: The researchers employed a semi-quantitative scoring system evaluating both the percentage of immunoreactive cells (0: <10%; 1: 10-<25%; 2: 25-<50%; 3: >50%) and staining intensity (0: negative; 1: weak; 2: moderate; 3: strong) [28]. The final immunoreactive score (0-9) was calculated by multiplying these two values, with scores of 0-3 considered negative and 4-9 positive [28]. This approach revealed distinct expression patterns, with cytochrome c detected in 68.9% of tumors compared to 54.4% of normal tissues, while cleaved caspase-3 was present in 24.1% of tumors versus only 3.4% of normal tissues [28].

Biomarker Quantification and Pathway Activation Scoring

Advanced computational approaches have been developed to quantify pathway activation levels based on biomarker expression patterns. The Pathway Activation Level (PAL) algorithm represents a sophisticated method that translates expression data into quantitative measures of pathway deregulation while considering pathway architecture [29]. This approach offers significant advantages over single-molecule biomarker analysis:

PAL Calculation Methodology:

- PAL is calculated as a weighted sum of logarithms of case-to-normal ratios for expression levels of all pathway genes [29].

- Weight coefficients range from -1 to 1 based on the activator or repressor role of each gene product within the pathway [29].

- An algorithmic approach assigns activator-repressor role coefficients to each pathway component based on pathway molecular architecture and interaction types [29].

- Gene-centric pathways can be automatically constructed as interacting networks around central genes of interest using whole-interactome models [29].

This methodology has demonstrated superior performance in cancer classification and prognostic assessment compared to individual gene expression biomarkers, with one study identifying 7,441 potential RNA biomarker associations for gene-centric pathways versus 24,349 for individual genes across 21 cancer types [29]. PAL values also exhibit better stability against experimental noise and reduced batch effects in both transcriptomic and proteomic data [29].

Comparative Biomarker Analysis in Cancer

Expression Patterns Across Cancer Types

The expression and clinical significance of intrinsic pathway biomarkers vary substantially across different cancer types, reflecting tissue-specific mechanisms of apoptosis regulation. BCL-2 family proteins demonstrate particularly diverse expression patterns that correlate with disease progression and treatment response:

Hematological Malignancies:

- BCL-2 is overexpressed in the majority of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cases due to BCL-2 gene hypomethylation and loss of miR-15/16 at 13q14 [22].

- Approximately 80-90% of follicular lymphomas and one-third of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL) exhibit constitutive BCL-2 expression caused by t(14;18) chromosomal translocation [22].

- Double-hit lymphomas, characterized by MYC and BCL-2 rearrangements, represent an aggressive DLBCL subtype with particularly poor prognosis [22].

Solid Tumors:

- SMAC/Diablo overexpression has been associated with increased sensitivity to apoptosis in various solid tumors, including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer, and glioblastoma [27].

- In gastric adenocarcinoma, cytochrome c expression was detected in 68.9% of tumor specimens compared to 54.4% of normal tissues, while DIABLO positivity was observed in 45.6% of tumors and 46.8% of normal tissues [28].

- Reduced SMAC/Diablo expression in cancer cells may inhibit apoptosis, thereby promoting survival and treatment resistance [28].

Table 2: Biomarker Alterations in Selected Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | BCL-2 Family Alterations | Cytochrome c Status | SMAC/Diablo Status | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLL | BCL-2 overexpression (hypomethylation, miR-15/16 loss) | Not well characterized | Controversial, mimetics show cytotoxic effects | Venetoclax sensitivity, resistance development |

| Follicular Lymphoma | BCL-2 overexpression (t(14;18) translocation) | Not well characterized | Not well characterized | Venetoclax monotherapy poor response |

| Gastric Adenocarcinoma | Not well characterized | 68.9% tumor positivity | 45.6% tumor positivity | Potential diagnostic utility |

| Solid Tumors (Various) | MCL-1 upregulation in resistance | Not well characterized | Overexpression in multiple types | Sensitivity to apoptosis |

Predictive and Prognostic Value

Biomarkers of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway provide valuable information for predicting treatment response and patient outcomes across diverse malignancies:

BCL-2 Family Biomarkers:

- BCL-2 expression levels significantly influence tumor susceptibility to BCL-2 inhibitors like venetoclax, with highest efficacy observed in CLL and AML [22].

- Overexpression of alternative anti-apoptotic proteins (MCL-1, BCL-XL) represents a common resistance mechanism to venetoclax, sequestering BIM displaced from BCL-2 [22].

- NOTCH1 mutations in CLL with trisomy 12 lead to decreased IRF4 and increased MCL-1 expression, contributing to venetoclax resistance [22].

- BH3 profiling serves as a functional biomarker for predicting chemotherapy sensitivity by measuring mitochondrial priming [23].

SMAC/Diablo Biomarkers:

- SMAC/Diablo expression levels correlate with increased sensitivity to apoptosis in multiple tumor types [27].

- Small-molecule SMAC mimetics demonstrate enhanced cytotoxic effects when combined with conventional chemotherapy, death receptor agonists, and targeted therapies [27].

- SMAC mimetics can increase tumor cell sensitivity to treatment, potentially allowing for dose reduction and minimized side effects [27].

Cytochrome c and Caspase Activation:

- Cleaved caspase-3 expression, a downstream consequence of cytochrome c release and apoptosome formation, was significantly elevated in gastric tumors (24.1%) compared to normal tissue (3.4%), indicating attempted apoptosis execution [28].

- Ki-67 proliferation index correlated with caspase-3 activation in gastric cancer, suggesting coordinated regulation of proliferation and cell death pathways [28].

Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Translation

Targeted Therapies and Resistance Mechanisms

Components of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway represent promising therapeutic targets, particularly in hematological malignancies:

BCL-2 Inhibition:

- Venetoclax (ABT-199), a highly selective oral BCL-2 antagonist, is FDA-approved for relapsed/refractory CLL with 17p deletion and for older adults with newly diagnosed AML who are unsuitable for intensive chemotherapy [22].

- Venetoclax functions as a BH3 mimetic that displaces pro-apoptotic proteins like BIM from BCL-2, activating BAX/BAK and triggering cytochrome c release [22].

- Resistance to venetoclax develops through multiple mechanisms, including upregulation of alternative anti-apoptotic proteins (MCL-1, BCL-XL), mutations in BCL-2 that reduce drug binding, and failure to execute apoptosis despite successful BCL-2 inhibition [22].

SMAC Mimetics:

- Small-molecule SMAC mimetics designed to mimic the AVPI N-terminal motif of SMAC/Diablo have been developed to promote apoptosis in cancer cells [27].

- These compounds bind to BIR domains of IAPs, particularly XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2, preventing caspase inhibition and promoting cell death [27].

- Several SMAC mimetics (including SM-406 and Genentech compounds) are undergoing clinical trials, with preclinical studies demonstrating enhanced efficacy when combined with conventional therapies [27].

- Potential side effects include elevated cytokine and chemokine levels in normal tissues, reflecting the role of IAPs in inflammatory signaling [27].

Biomarker-Driven Treatment Strategies

The development of robust biomarkers has enabled more personalized therapeutic approaches targeting the intrinsic apoptotic pathway:

BH3 Profiling:

- This functional assay measures mitochondrial priming by exposing isolated mitochondria to BH3 peptides and quantifying membrane depolarization or cytochrome c release [23].

- BH3 profiling can identify tumors dependent on specific anti-apoptotic proteins, guiding selection of appropriate targeted therapies [23].

- The technique has been proposed as a biomarker strategy for predicting chemotherapy sensitivity in diverse cancer types [23].

Pathway Activation Scoring:

- Algorithmic pathway analysis using PAL provides a comprehensive assessment of intrinsic pathway status beyond individual biomarker expression [29].

- Gene-centric pathways have demonstrated superior biomarker performance compared to individual genes for tumor classification and outcome prediction [29].

- Computer-built pathways represent a credible alternative to manually curated pathways, reducing investigator bias and enabling rapid biomarker development [29].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Intrinsic Pathway Biomarker Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Proteins | Recombinant Human BCL2 (His-tagged) [24] | Protein-protein interaction studies, antibody production | Various protein lengths (1-239 aa, 101-239 aa, 50-150 aa) |

| Antibodies for IHC | DIABLO mouse monoclonal (Cell Signaling) [28] | Tissue localization and expression analysis | 1:200 dilution for gastric cancer TMA |

| AIF rabbit polyclonal (H-300) [28] | Mitochondrial and cytoplasmic staining | 1:400 dilution, cytoplasmic expression pattern | |

| Cytochrome c goat polyclonal (C-20) [28] | Detection of mitochondrial release | 1:500 dilution, cytoplasmic expression | |

| Cleaved caspase-3 rabbit polyclonal [28] | Apoptosis execution marker | 1:100 dilution, cytoplasmic pattern | |

| Cell Lysates | Human BCL2 Knockdown Cell Lysate [24] | Western blot controls, functional studies | HeLa cell source |

| Human CASP9 Knockdown Cell Lysate [24] | Apoptosome formation studies | HeLa cell source | |

| Research Kits | LSAB+ System-HRP [28] | IHC detection | Biotin-streptavidin amplification |

| Liquid DAB+ Substrate Chromogen [28] | IHC visualization | Permanent brown staining |

Visualizing the Intrinsic Apoptotic Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular events and biomarkers of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway:

Diagram 1: Intrinsic Apoptotic Pathway Signaling. This diagram illustrates the sequence of events from initial cellular stress to apoptosis execution, highlighting the central regulatory role of BCL-2 family proteins, mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), and the coordinated actions of cytochrome c and SMAC/Diablo.

The intrinsic apoptotic pathway biomarkers—BCL-2 family proteins, cytochrome c, and SMAC/Diablo—provide critical insights into cellular life-and-death decisions with profound implications for cancer biology and therapy. These biomarkers function as an integrated system rather than isolated entities, with BCL-2 proteins regulating the initial commitment step of MOMP, cytochrome c activating the caspase cascade through apoptosome formation, and SMAC/Diablo removing inhibitory blocks on apoptosis execution. Their coordinated analysis offers superior diagnostic and prognostic information compared to individual biomarker assessment, as demonstrated by advanced computational approaches like pathway activation level scoring.

The clinical translation of these biomarkers is particularly evident in hematological malignancies, where BCL-2 inhibition with venetoclax has revolutionized treatment for specific patient subsets. However, resistance mechanisms highlight the complexity of apoptotic regulation and the need for comprehensive biomarker assessment that includes alternative anti-apoptotic family members and functional mitochondrial priming. Ongoing development of SMAC mimetics and combination strategies offers promising avenues for enhancing therapeutic efficacy across diverse cancer types. As biomarker technologies continue to evolve, particularly with algorithmic pathway analysis and functional assays, personalized targeting of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway will likely expand, providing new opportunities for cancer therapy and overcoming treatment resistance.

The extrinsic apoptosis pathway, a fundamental form of programmed cell death, is initiated at the cell surface through specific death receptors and propagates intracellular signals via defined molecular interactions [30]. This pathway is critical for maintaining cellular homeostasis, eliminating damaged or dangerous cells, and proper immune system function [31]. The core molecular machinery of this pathway consists of death receptors, adaptor proteins, and initiator caspases that together determine cellular fate [32]. Research into these components provides crucial biomarkers for understanding disease mechanisms, particularly in cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and inflammatory conditions [31] [32]. This guide objectively compares the key biomarkers—death receptors, caspase-8, and FADD—that researchers utilize to monitor and quantify extrinsic pathway activation, providing experimental data and methodologies relevant for drug development professionals.

Core Biomarkers of the Extrinsic Pathway

Death Receptors: The Initiation Complex

Death receptors are transmembrane proteins belonging to the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily that contain a conserved cytoplasmic death domain (DD) essential for apoptosis signaling [30]. These receptors function as the entry point for extrinsic death signals by binding specific extracellular ligands such as FasL (for CD95/Fas), TRAIL (for TRAIL-R1/DR4 and TRAIL-R2/DR5), and TNF (for TNFR1) [30] [33].

Key Comparative Features:

- Structural Organization: All death receptors share characteristic cysteine-rich extracellular domains and a conserved intracellular death domain (∼80 amino acids) that mediates homotypic protein interactions [30].

- Signaling Mechanism: Upon ligand-induced trimerization, death receptors undergo conformational changes that facilitate the recruitment of intracellular adaptor proteins [30] [33].

- Research Significance: Different death receptors activate overlapping but distinct downstream pathways. For example, TNFR1 recruitment of FADD requires the intermediate adapter TRADD, while CD95 and TRAIL receptors recruit FADD directly [30] [33].

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Major Death Receptors

| Death Receptor | Alternative Names | Ligand | Adapter Recruitment | Primary Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD95/Fas | TNFRSF6, Apo-1 | FasL | Direct FADD binding | Autoimmunity, liver disease, cancer immunotherapy |

| TRAIL-R1 | DR4 | TRAIL | Direct FADD binding | Cancer research (selective tumor cell apoptosis) |

| TRAIL-R2 | DR5 | TRAIL | Direct FADD binding [33] | Cancer therapeutics, metastasis inhibition |

| TNFR1 | TNFRSF1a | TNF | FADD via TRADD intermediate [30] | Inflammation, sepsis, neurodegenerative diseases |

FADD: The Critical Adaptor Protein

Fas-associated death domain (FADD) serves as the essential adaptor protein that bridges activated death receptors to downstream effector molecules [34]. FADD contains two primary domains: a C-terminal death domain (DD) that interacts with death receptors and an N-terminal death effector domain (DED) that engages initiator caspases [34] [32].

Research Applications:

- Molecular Recruitment: FADD's DD binds to the trimerized death receptors through homotypic interactions with a 3:1 (receptor:FADD) stoichiometry [30].

- Complex Formation: The DED of FADD undergoes a conformational change upon receptor binding, exposing its binding surface to recruit procaspase-8 through DED-DED interactions [34].

- Experimental Evidence: Structural studies using mutagenesis (e.g., F122A/I128A mutations in caspase-8 DED) demonstrate that specific residues are critical for stable FADD-caspase-8 complex formation [34].

Caspase-8: The Initiator Protease

Caspase-8 is the primary initiator caspase in the extrinsic pathway, functioning as a cysteine-aspartic protease that initiates the apoptotic cascade [30] [32]. It exists as an inactive zymogen (procaspase-8) in living cells, becoming activated through proximity-induced dimerization and autocleavage upon recruitment to the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) [30].

Key Research Characteristics:

- Structural Domains: Caspase-8 contains two N-terminal death effector domains (DEDs), a large protease subunit (p18/p20), and a small protease subunit (p10) [32].

- Activation Mechanism: Within the DED filaments of the DISC, procaspase-8 molecules form homodimers that undergo autoproteolytic cleavage at D384 (human) and D387 (mouse) for partial activation, followed by further processing to release the fully mature enzyme [30].

- Regulatory Checkpoints: Phosphorylation at specific residues (e.g., Y380) can regulate caspase-8 activity without affecting DISC recruitment, providing a regulatory mechanism for apoptosis control [30].

Table 2: Quantitative Biomarker Measurements in Experimental Models

| Biomarker | Detection Method | Sample Type | Key Measurable Parameters | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death Receptors | Flow cytometry, IHC | Cell surface, tissue sections | Receptor density, ligand binding affinity | TRAIL-R2 activation recruits FADD/caspase-8 within 1 minute [33] |

| FADD | Western blot, GST pull-down | Cell lysates, purified complexes | Protein-protein interaction kinetics, phosphorylation status | DED-DED interaction KD = 250-1000 nM by Biacore [34] |

| Caspase-8 | ELISA, IHC, activity assays | Plasma, serum, tissue extracts | Procaspase-8, cleaved fragments, enzymatic activity | Cleavage at D384/D387 indicates activation; phosphorylation at Y380 inhibits apoptosis [30] |

| FADD-Caspase-8 Complex | Co-immunoprecipitation, BIO-TEM | Immunoprecipitated DISC | Complex formation, stoichiometry, spatial organization | FADD:caspase-8 ratio averages 1:6 in stoichiometric studies [30] |

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Analysis

DISC Immunoprecipitation and Analysis

This protocol isolates and characterizes the Death-Inducing Signaling Complex (DISC) to study early events in extrinsic apoptosis activation [33].

Methodology:

- Cell Stimulation: Treat cells (e.g., BJAB, Jurkat, K562, or MCF-7) with death receptor ligands (e.g., TRAIL at 100-500 ng/mL) for 1-60 minutes at 37°C [33].

- Cell Lysis: Use mild lysis buffers (1% Triton X-100, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl) with protease inhibitors to preserve protein complexes.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate lysates with specific death receptor antibodies (e.g., anti-TRAIL-R2) coupled to protein A/G beads for 2-4 hours at 4°C [33].

- Complex Analysis: Wash beads thoroughly and elute bound proteins for Western blotting to detect co-precipitated FADD, caspase-8, and other DISC components.

Key Applications: Determining composition and kinetics of DISC assembly; comparing receptor signaling specificity; testing drug effects on complex formation [33].

FADD-Caspase-8 Interaction Mapping

This biophysical approach characterizes the direct molecular interactions between FADD and caspase-8 death effector domains [34].

Methodology:

- Protein Purification: Express and purify recombinant FADD DED (residues 1-83) and caspase-8 DEDs (residues 1-188) using His-tagged or GST-tagged systems in E. coli [34].

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Generate specific point mutations in caspase-8 DED (e.g., Y8D/I128A, E12A/I128A, F122A/I128A) to identify critical interaction residues [34].

- Binding Assays:

- GST Pull-down: Incubate GST-tagged FADD DED with His-tagged caspase-8 DED mutants, capture on glutathione sepharose, and detect bound proteins by Western blot [34].

- Surface Plasmon Resonance: Immobilize FADD DED on CM5 chip and measure binding kinetics with caspase-8 DED concentrations (250-5000 nM) using Biacore systems [34].

- Structural Analysis: Determine crystal structures of caspase-8 DED mutants (e.g., F122A/I128A) at 1.7 Å resolution to visualize interaction interfaces [34].

Key Applications: Identifying critical interaction residues; quantifying binding affinities; guiding drug discovery targeting DED interactions.

Caspase-8 Activity Monitoring

This functional assay measures caspase-8 enzymatic activity as a direct indicator of extrinsic pathway activation [31].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare cell lysates or fractionated cellular compartments from treated and control cells.

- Activity Assay: Use fluorogenic or colorimetric substrates (e.g., IETD-pNA) that release detectable signals upon cleavage by active caspase-8.

- Quantification: Measure signal generation over time and compare to standard curves of recombinant active caspase-8.

- Specificity Controls: Include caspase-8 specific inhibitors to confirm signal specificity.

Key Applications: Pharmacodynamic monitoring of drug efficacy; determining apoptotic thresholds; correlating caspase activation with cell death outcomes [31].

Signaling Pathway Visualization

Figure 1: Extrinsic Apoptosis Pathway Molecular Interactions. This diagram illustrates the core signaling cascade from death receptor activation to apoptosis execution, highlighting the critical role of FADD and caspase-8 as central biomarkers. Regulatory mechanisms involving cFLIP are shown in green/red to indicate their dual role in promoting or inhibiting apoptosis depending on cellular context [30] [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Extrinsic Pathway Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Functional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Proteins | His-tagged FADD DED (1-83), Caspase-8 DEDs (1-188) [34] | Biophysical interaction studies, structural biology | Enables precise measurement of DED-DED interactions without full-length protein complexity |

| Cell Line Models | FADD-deficient Jurkat cells, Caspase-8-deficient cells [33] | Genetic validation of pathway components | Essential for establishing necessity of specific biomarkers in death receptor signaling |

| Activation Ligands | Recombinant TRAIL, Anti-Fas agonistic antibodies [33] | Specific pathway activation | TRAIL particularly valuable for cancer studies due to selective tumor cell apoptosis |

| Detection Antibodies | Anti-FADD, Anti-Caspase-8 (cleaved and total), Anti-death receptors [34] [33] | Western blot, immunoprecipitation, flow cytometry | Cleavage-specific antibodies critical for distinguishing active vs. inactive caspase-8 |

| Inhibitors/Mutants | cFLIP overexpression constructs, Caspase-8 phosphorylation mutants (Y380F) [30] [32] | Pathway modulation studies | Phosphorylation mutants help elucidate regulatory mechanisms controlling caspase-8 activity |

Comparative Analysis and Research Applications

The core biomarkers of the extrinsic pathway function as an integrated system with distinct but interconnected roles. Death receptors serve as the specific recognition components, FADD as the essential adaptor, and caspase-8 as the enzymatic activator. Each biomarker provides unique research insights:

Death Receptors offer target specificity, with different receptors activating context-dependent signaling outcomes. TRAIL receptors are particularly valuable in cancer research due to their ability to selectively induce apoptosis in transformed cells while sparing normal cells [33].

FADD represents a convergence point in extrinsic signaling, with its essential role demonstrated across multiple death receptor pathways. Structural studies reveal that specific residues (F122, I128) in caspase-8 DED are critical for FADD binding, providing targets for potential therapeutic intervention [34].

Caspase-8 serves as the critical decision point between apoptosis and alternative cell fates. Its activation status provides a definitive biomarker for extrinsic pathway engagement, while its regulatory modifications (phosphorylation, cFLIP binding) offer insights into pathway modulation in different disease contexts [30] [32].

The integrated analysis of these biomarkers provides researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for investigating cell death mechanisms, screening potential therapeutics, and understanding disease pathologies involving dysregulated apoptosis.

Cellular behavior is governed by a complex interplay between intrinsic and extrinsic signaling pathways. The integration point of these signals determines critical cellular outcomes, including proliferation, differentiation, and programmed cell death (apoptosis). The extrinsic pathway of apoptosis initiates outside the cell when extracellular conditions dictate cell death, while the intrinsic pathway activates internally in response to cellular stress or damage [35]. Understanding the molecular convergence of these pathways is essential for advancing biomarker research and developing targeted therapies, particularly in oncology and immunology. This guide provides a comparative analysis of key biomarkers and experimental methodologies used to dissect these integrated signaling networks.

Key Signaling Pathways and Their Molecular Regulators

Core Apoptosis Pathways

The apoptotic signaling network represents a paradigm of intrinsic-extrinsic pathway integration. The extrinsic apoptosis pathway begins with ligand binding to death receptors (e.g., Fas, TNFR1) at the cell surface, leading to formation of the Death-Inducing Signaling Complex (DISC) and activation of caspase-8 [35]. This initiates a proteolytic cascade that executes the apoptotic program. Meanwhile, the intrinsic apoptosis pathway activates in response to internal stressors like DNA damage, oxidative stress, or oncogene activation, culminating in mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) and release of cytochrome c [35]. The convergence point between these pathways occurs at several levels, particularly through the caspase activation cascade and BID cleavage, which amplifies the death signal.

Mechanotransduction Pathways

Beyond biochemical signaling, mechanical cues from the cellular microenvironment serve as critical extrinsic signals that influence intrinsic pathway activation. Cells sense physical properties like matrix stiffness, fluid shear stress, and compressive stress through mechanosensors including integrins, Piezo channels, and YAP/TAZ signaling [36]. These mechanical signals undergo mechanotransduction into biochemical responses that regulate fundamental cellular processes including morphogenesis, immunity, and tumor progression [36]. The tumor microenvironment exhibits distinct biomechanical properties that influence therapeutic responses, particularly in desmoplastic cancers like pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [36].

Wnt Signaling in Cellular Homeostasis

The Wnt signaling pathway exemplifies how intrinsic and extrinsic signals integrate to regulate tissue homeostasis and development. This pathway activates through extrinsic Wnt ligands binding to Frizzled receptors, which transduce signals to intrinsic effectors including β-catenin [37]. In the canonical pathway, signal transduction inhibits the β-catenin destruction complex (APC, Axin, GSK3β), allowing β-catenin accumulation and nuclear translocation to activate target genes [37]. Dysregulated Wnt signaling occurs in many cancers through mutations in pathway components like APC or CTNNB1 (encoding β-catenin), leading to constitutive pathway activation independent of extrinsic signals [37].

Table 1: Key Signaling Pathways and Their Components

| Pathway | Extrinsic Signals | Membrane Receptors | Intrinsic Signal Transducers | Cellular Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrinsic Apoptosis | FasL, TRAIL, TNF-α | Fas, DR4/5, TNFR1 | FADD, caspase-8, caspase-3 | Membrane blebbing, DNA fragmentation, phagocytosis |

| Intrinsic Apoptosis | Cellular stress (DNA damage, hypoxia) | N/A | p53, Bcl-2 family, cytochrome c, caspase-9 | Mitochondrial permeability, caspase activation |

| Wnt Signaling | Wnt proteins | Frizzled, LRP5/6 | β-catenin, APC, GSK-3β, TCF/LEF | Proliferation, differentiation, stem cell maintenance |

| Mechanotransduction | Matrix stiffness, fluid shear stress | Integrins, Piezo channels | YAP/TAZ, Rho GTPases | Gene expression, cytoskeletal reorganization, migration |

Comparative Analysis of Pathway Biomarkers

Apoptosis Pathway Biomarkers

Biomarker profiling enables researchers to distinguish pathway activation and identify convergence points. The extrinsic pathway features characteristic biomarkers including death receptors (Fas, TNFR1), adapter proteins (FADD, TRADD), and initiator caspases (caspase-8, -10) [35]. The intrinsic pathway biomarkers include stress sensors (p53), Bcl-2 family proteins (BAX, BAK, Bid), mitochondrial components (cytochrome c, SMAC/Diablo), and caspase-9 [35]. Integrated biomarkers that reflect pathway convergence include executioner caspases (caspase-3, -7), DNA fragmentation factors (CAD/ICAD), and cleaved substrates like PARP.

Table 2: Biomarkers of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Apoptosis Pathways

| Biomarker Category | Extrinsic Pathway Markers | Intrinsic Pathway Markers | Convergence Point Markers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initiation Proteins | Fas, TNFR1, TRAIL-R1/2 | p53, Bim, Bax, Bak | tBid, caspase-2 |

| Adapter/Mediator Proteins | FADD, TRADD, Daxx | Apaf-1, cytochrome c | PIDDosome |

| Protease Activators | Caspase-8, caspase-10 | Caspase-9 | Caspase-3, caspase-7 |

| Inhibitory Proteins | FLIP, cIAP1/2 | Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1 | IAP family, survivin |

| Mitochondrial Factors | N/A | SMAC/Diablo, Omi/HtrA2, AIF | N/A |

| Effector Proteins | N/A | N/A | ICAD/CAD, cleaved PARP |

Wnt Pathway Biomarkers

Wnt pathway biomarkers provide critical insights into developmental signaling and carcinogenesis. Key ligands and receptors include various Wnt proteins and Frizzled receptors, particularly FZD7 in gastric cancer [37]. Intracellular transducers include β-catenin, APC, Axin, and GSK-3β, with β-catenin stabilization and nuclear translocation serving as a primary activation marker [37]. Negative regulators encompass extracellular antagonists like Dickkopf (DKK) and secreted Frizzled-related proteins (sFRPs), while target genes include c-Myc, cyclin D1, and survivin [37]. Mutational analysis of APC and CTNNB1 genes provides predictive biomarkers for Wnt pathway activation across multiple cancer types.

Biomarkers in Targeted Protein Degradation

The emerging field of targeted protein degradation reveals new dimensions of intrinsic-extrinsic signaling integration. PROTAC molecules function as extrinsic诱导剂 that bridge target proteins to E3 ubiquitin ligases, exploiting intrinsic degradation machinery [38]. Key regulatory biomarkers in this process include ubiquitin chain types (K29/K48-branched chains), E2 conjugating enzymes (UBE2G, UBE2R), and regulatory factors like TRIP12 that promote branched ubiquitination [38]. Signaling pathways that modulate degradation efficiency include PARP ribosylation, HSP90-mediated protein stabilization, and PERK-regulated unfolded protein response, identified through chemical enhancer screens [38].

Experimental Methodologies for Pathway Analysis

Mechanotransduction Assays