Mitochondrial Membrane Potential and pH Control: From Molecular Mechanisms to Disease Implications and Advanced Measurement Techniques

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the intricate relationship between mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) and pH gradient (ΔpH), the two components of the proton motive force essential for ATP...

Mitochondrial Membrane Potential and pH Control: From Molecular Mechanisms to Disease Implications and Advanced Measurement Techniques

Abstract

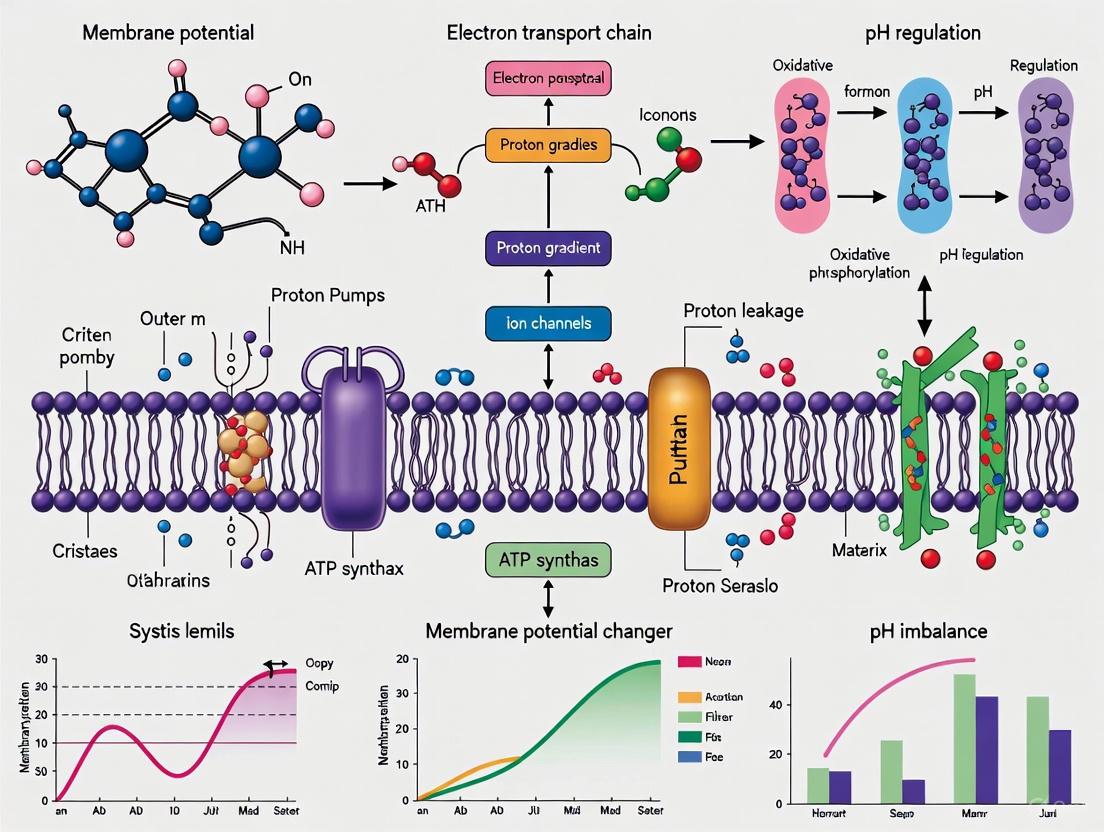

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the intricate relationship between mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) and pH gradient (ΔpH), the two components of the proton motive force essential for ATP production and cellular survival. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biophysics of the electrochemical gradient, details cutting-edge and traditional methodologies for measuring these parameters, addresses common experimental challenges and artifacts, and discusses the critical role of ΔΨm/ΔpH dysregulation in diseases such as ischemia-reperfusion injury, cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders. The content synthesizes validation strategies for different techniques and highlights emerging therapeutic opportunities targeting mitochondrial bioenergetics.

The Proton Motive Force: Deconstructing the Energetic Core of the Mitochondrion

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Consistently Low or Unmeasurable ΔΨm

Problem: Fluorescent dye assays (e.g., JC-1, TMRM) indicate a lower-than-expected mitochondrial membrane potential, suggesting poor energetic state or uncoupling.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Uncoupling [1] [2] | Add an uncoupler like FCCP. If ΔΨm collapses further, the issue is elsewhere. If ΔΨm is already minimal, the mitochondria may be already uncoupled. | Check for contamination with uncoupling agents (e.g., ionophores). Use inhibitors like oligomycin to block ATP synthase hydrolysis. |

| Respiratory Chain Inhibition [1] [3] | Measure oxygen consumption rate (OCR). Low basal OCR suggests impaired electron transport chain (ETC) function. | Use substrates for specific ETC complexes to isolate the blocked segment. Ensure adequate metabolite supply (e.g., pyruvate, succinate). |

| ATP Synthase Reversal [1] [4] | Inhibit ATP synthase with oligomycin. If ΔΨm increases, it indicates the synthase was hydrolyzing ATP to pump protons. | Utilize the ATPase inhibitory factor 1 (IF1) or ensure adequate ATP levels to prevent reverse activity. |

| Proton Leak [4] [2] | Calculate the proton leak fraction from OCR measurements. High leak under oligomycin indicates intrinsic or protein-mediated leak. | Investigate expression levels of uncoupling proteins (UCPs). Use UCP inhibitors if appropriate. |

Issue 2: Excessive ΔΨm (Hyperpolarization) and Associated Toxicity

Problem: Mitochondria exhibit sustained, abnormally high membrane potential, which can increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) production.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibition of ATP Synthesis [1] | Measure cellular ATP/ADP ratio. A low ratio with high ΔΨm suggests a blockage in ATP synthesis or export. | Check for inhibition of ATP synthase (e.g., oligomycin) or the adenine nucleotide translocator (ANT). |

| Reduced Metabolic Demand | N/A | Correlate with overall cellular activity. Hyperpolarization may be transient and physiological. |

| Compromised Uncoupling Mechanisms [2] | Assess expression and function of UCPs. | Investigate regulatory pathways for UCPs. Induce mild uncoupling to safely dissipate excess potential. |

Issue 3: Inconsistent or Heterogeneous ΔΨm Readings Across a Cell Population

Problem: High variability in ΔΨm measurements between cells or between mitochondria within a single cell.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Normal Physiological Heterogeneity [1] [2] | Use high-resolution live-cell imaging. Heterogeneity may correlate with cell cycle stage, metabolic activity, or mitochondrial subpopulations. | Establish a baseline for "normal" heterogeneity in your model system. Analyze subcellular mitochondrial populations separately. |

| Onset of Mitophagy [2] | Co-stain with mitophagy markers (e.g., PINK1, Parkin). Mitochondria with low ΔΨm may be targeted for degradation. | This is often a healthy quality control process. If excessive, investigate causes of widespread damage. |

| Artifacts from Dye Loading/Measurement [1] | Validate dye concentrations, loading times, and proper use of quench/dequench protocols. Compare multiple dyes (e.g., JC-1 vs. TMRM). | Follow established protocols rigorously. Include appropriate controls (e.g., FCCP for collapse, inhibitors for specific conditions). |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental relationship between ΔΨm and ΔpH? They are the two components of the proton-motive force (PMF). The PMF is the total energy stored in the electrochemical proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane and is calculated as PMF = ΔΨ - (2.3RT/F)ΔpH [3] [4]. In mitochondria, the electrical potential (ΔΨm) is the dominant component, typically around -170 to -180 mV, while the chemical gradient (ΔpH) is smaller, contributing about a quarter of the total PMF [2].

Q2: Why is my ΔΨm reading unstable after adding a drug intended to modulate metabolism? Many drugs, especially those in development, have off-target effects on mitochondrial function. The compound may be acting as an uncoupler, an ETC inhibitor, or an ionophore that disturbs the membrane integrity. It is recommended to perform a Seahorse XF Analyzer assay or similar to profile the bioenergetic function and pinpoint the specific complex or process affected [1] [2].

Q3: Can ΔΨm be too high? Why is that a problem? Yes. While a strong ΔΨm is necessary for ATP production, sustained hyperpolarization can be pathological. An excessively high ΔΨm increases the reduction of oxygen at the ETC, leading to a significant leak of electrons and a surge in superoxide and other ROS production. This oxidative stress can damage cellular components and trigger cell death pathways [1] [2].

Q4: How does ΔΨm directly control mitochondrial quality control (mitophagy)? A sustained loss of ΔΨm in a damaged mitochondrion is a primary signal for its elimination. Reduced ΔΨm stabilizes the PINK1 kinase on the outer membrane, which then recruits the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin. Parkin ubiquitinates outer membrane proteins, marking the entire organelle for degradation via autophagy in a process called mitophagy [2].

Table 1: Components of the Proton-Motive Force (PMF)

| Parameter | Typical Value in Mitochondria | Contribution to Total PMF | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔΨm (Electrical Gradient) | ~ -170 to -180 mV [3] [2] | Major contributor (~75%) [2] | Negative inside the matrix. Measured with potentiometric dyes. |

| ΔpH (Chemical Gradient) | ~ 0.4 pH units [2] | Minor contributor (~25%) [2] | Matrix is more alkaline (pH ~7.8) than the intermembrane space (pH ~7.4). |

| Total PMF | ~ 180-200 mV [4] | 100% | Minimum ~170 mV (or ~50 kJ/mol) is required for ATP synthesis [3] [5]. |

Table 2: Key Experimental Inhibitors and Uncouplers

| Reagent | Target/Function | Effect on ΔΨm | Primary Use in Experimentation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligomycin | ATP Synthase (F0 subunit) [4] | Increases (by blocking consumption) | To assess proton leak or measure ATP-linked respiration. |

| FCCP | Uncoupler (H+ ionophore) [2] | Collapses (dissipates the gradient) | To measure maximum respiratory capacity; used as a control to collapse ΔΨm in dye assays. |

| Rotenone | Complex I [3] | Decreases (halts proton pumping) | To inhibit NADH-linked respiration. |

| Antimycin A | Complex III [3] | Decreases (halts proton pumping) | To inhibit ETC function completely. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring ΔΨm using JC-1 with Fluorescence Microscopy

Principle: JC-1 is a cationic dye that accumulates in mitochondria in a potential-dependent manner. At high ΔΨm, it forms aggregates that emit red light (~590 nm). At low ΔΨm, it remains in a monomeric state that emits green light (~529 nm). The red/green ratio is a quantitative measure of ΔΨm [1].

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Plate cells on glass-bottom culture dishes and grow to 50-70% confluency.

- Dye Loading: Incubate cells with 2-5 µM JC-1 in culture media for 15-30 minutes at 37°C in the dark.

- Washing: Gently rinse cells with pre-warmed PBS or dye-free media to remove excess extracellular dye.

- Imaging: Acquire images using a fluorescence microscope with appropriate filter sets for FITC (green monomers) and TRITC (red J-aggregates).

- Analysis: Calculate the ratio of red fluorescence intensity to green fluorescence intensity for individual mitochondria or whole cells. Include controls:

- High ΔΨm Control: Cells treated with a complex I or II substrate.

- Low ΔΨm Control: Cells treated with 1-10 µM FCCP to fully collapse the gradient.

Protocol 2: Calibrating ΔΨm using a K+ Gradient with Valinomycin

Principle: The ionophore valinomycin makes the membrane permeable to K+. By controlling the K+ concentration inside and outside of the mitochondria ([K+]~in~ and [K+]~out~), the membrane potential can be set to a known value using the Nernst equation: ΔΨm = -61.5 log([K+]~in~ / [K+]~out~) at 37°C [1].

Procedure:

- Suspend Mitochondria: Isolate mitochondria in a K+-free sucrose-based buffer.

- Create K+ Gradient: Add aliquots of mitochondria to a series of tubes containing buffers with known, varying concentrations of KCl (e.g., 0.1, 1, 10 mM).

- Apply Valinomycin: Add a low concentration of valinomycin (e.g., 100 nM) to each tube to allow K+ equilibration.

- Add Dye and Measure: Introduce a potentiometric dye like TMRM and record the fluorescence.

- Generate Standard Curve: Plot the fluorescence signal (or its log) against the calculated Nernst potential for each K+ concentration. This curve can be used to convert fluorescence readings from experimental samples into millivolt (mV) estimates of ΔΨm.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| JC-1 (5,5',6,6'-tetrachloro-1,1',3,3'-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide) | Ratiometric fluorescent dye for monitoring ΔΨm; green monomer at low potential, red J-aggregate at high potential [1]. |

| TMRM (Tetramethylrhodamine, methyl ester) / TMRE | Cationic, fluorescent dye that accumulates in mitochondria in a ΔΨm-dependent manner; used for quantitative potential measurement. |

| FCCP (Carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone) | Proton ionophore and potent uncoupler; collapses the proton gradient and ΔΨm, used as a critical control [2]. |

| Oligomycin | ATP synthase inhibitor; used to prevent reverse activity (ATP hydrolysis) and to probe the proton leak component of respiration [4]. |

| Valinomycin | K+ ionophore; used to calibrate ΔΨm measurements by clamping the potential to known values via the K+ diffusion potential [1]. |

| Antimycin A | Inhibitor of Complex III; used to shut down the electron transport chain for controlled studies of ΔΨm decay [3]. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Chemiosmotic Theory Framework

Mitochondrial Quality Control via ΔΨm

Experimental Workflow for ΔΨm Investigation

The mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) is a critical component of cellular bioenergetics, representing the electrical component of the proton motive force that drives adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis. This potential is generated primarily through the coordinated activity of specific complexes within the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC). Complexes I, III, and IV function as proton pumps, translocating protons from the mitochondrial matrix to the intermembrane space and creating an electrochemical gradient [6] [1] [7]. The energy stored in this gradient is then harnessed by ATP synthase (Complex V) to phosphorylate adenosine diphosphate (ADP), producing ATP [6] [7]. This article provides a technical guide for researchers investigating ΔΨm, with a specific focus on troubleshooting common experimental challenges related to its generation by Complexes I, III, and IV.

FAQ: Core Concepts of ΔΨm Generation

Q1: Which ETC complexes are directly responsible for generating ΔΨm, and what are their specific contributions? Complexes I, III, and IV are the primary proton-pumping complexes responsible for building ΔΨm. Their specific roles are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Proton-Pumping Complexes of the Electron Transport Chain

| Complex | Common Name | Electron Transfer | Proton Translocation (H+/2e-) | Key Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex I | NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase | NADH → Coenzyme Q | 4 H+ from matrix to IMS [6] | Rotenone [8] |

| Complex III | Cytochrome bc₁ complex | Coenzyme Q → Cytochrome c | 4 H+ (via the Q-cycle) [6] | Antimycin A [7] |

| Complex IV | Cytochrome c oxidase | Cytochrome c → O₂ | 2 H+ from matrix to IMS [6] | Cyanide, Azide [7] |

Q2: Why is Complex II not a contributor to ΔΨm? Complex II (succinate dehydrogenase) participates in the ETC by oxidizing succinate to fumarate and reducing ubiquinone to ubiquinol. However, its function is not coupled to proton translocation across the inner mitochondrial membrane [6] [7]. It serves as an auxiliary entry point for electrons from FADH2 into the ETC but does not directly contribute to the proton gradient.

Q3: How does a compromised proton gradient affect mitochondrial function beyond ATP production? ΔΨm is not only essential for ATP synthesis but also serves as a key indicator of mitochondrial health and a driver of critical cellular processes. A sustained drop in ΔΨm can induce a loss of cell viability and is implicated in various pathologies [1]. Furthermore, ΔΨm provides the electrophoretic force for importing proteins into the mitochondria and transporting ions, such as calcium and iron, which are necessary for healthy mitochondrial function and biogenesis of Fe-S clusters [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Inconsistent or Lower-Than-Expected ΔΨm Readings Unexpectedly low ΔΨm measurements can stem from issues with the ETC complexes or experimental conditions.

- Potential Cause: Inhibition of Proton-Pumping Complexes. Contamination from environmental toxins or residual cleaning agents can inhibit ETC complexes. For instance, cyanide and azide inhibit Complex IV, while rotenone inhibits Complex I [7] [8].

- Solution:

- Validate Reagent Purity: Ensure all buffers and media are prepared with high-grade water and reagents. Test for the presence of inhibitors.

- Confirm Substrate Integrity: Use fresh, properly aliquoted substrates for respiration (e.g., succinate, glutamate/malate). Degraded substrates will limit electron flow.

- Employ an Inhibitor Cocktail: Systematically use specific inhibitors to isolate the faulty complex.

- Add rotenone (Complex I inhibitor); a failure to recover ΔΨm with subsequent succinate (Complex II substrate) addition suggests broader membrane damage.

- If ΔΨm is established with succinate but collapses upon adding antimycin A (Complex III inhibitor), it confirms proton pumping by Complex III is functional.

Problem 2: High Background ROS Interfering with ΔΨm Assays Excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production is both a consequence and a cause of a compromised ΔΨm.

- Potential Cause: Pathological Electron Leakage. When electron flow through the ETC is impaired (e.g., by inhibition, hypoxia, or mutations in ETC subunits), electrons can leak prematurely and react with oxygen, generating superoxide (O₂•–) [8]. Complexes I and III are major sites of ROS production [8]. This is particularly relevant in cancer research, where oncogenic pathways can hijack the ETC to increase its ROS-producing capacity [8].

- Solution:

- Optimize Assay Conditions: Reduce ambient light exposure for fluorescent dyes and minimize sample preparation time.

- Use Antioxidants Judiciously: Include low concentrations of membrane-permeable antioxidants like MitoTEMPO (a mitochondria-targeted superoxide scavenger) in your assays to mitigate ROS interference [8]. Note: High concentrations may artificially suppress physiological ROS signaling.

- Investigate ETC Supercomplex Assembly: Defects in the assembly of ETC supercomplexes can increase electron leakage and ROS. Assess the integrity of supercomplexes via blue native PAGE [8] [9].

Problem 3: Failure to Link ΔΨm to Functional ATP Output A high ΔΨm does not always correlate with high ATP production, indicating a possible uncoupling or dysfunction in ATP synthase.

- Potential Cause: Reverse Operation of ATP Synthase. Under conditions where the proton gradient is dissipated (e.g., after ETC inhibition), the ATP synthase (Complex V) can run in reverse, hydrolyzing ATP to pump protons and maintain ΔΨm, thereby consuming cellular ATP [1].

- Solution:

- Inhibit ATP Synthase: Use oligomycin to block the F0 subunit of ATP synthase. This will prevent reverse activity and allow for a pure measurement of the ETC-generated ΔΨm [9].

- Measure Concurrently: Use real-time assays that simultaneously monitor ΔΨm (e.g., with TMRM) and ATP levels (e.g., with a FRET-based ATP sensor) to directly observe the coupling efficiency [10].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Measuring ΔΨm with TMRM/JC-1 via Fluorescence Microscopy

This protocol outlines the steps for assessing ΔΨm in live cells using potentiometric dyes.

- Principle: Cationic dyes like Tetramethylrhodamine Methyl Ester (TMRM) and JC-1 accumulate in the mitochondrial matrix in a ΔΨm-dependent manner. TMRM fluorescence intensity is quantitative, while JC-1 exhibits a shift from green (monomer, low ΔΨm) to red (J-aggregates, high ΔΨm) [11].

- Procedure:

- Cell Loading: Incubate cells with 20-200 nM TMRM or 2-5 µM JC-1 in culture medium for 20-40 minutes at 37°C [11]. The optimal concentration must be determined empirically, as low concentrations (e.g., 1.35-2.7 nM TMRM) are required to visualize spatial gradients between the cristae and inner boundary membranes [10].

- Washing & Equilibration: Replace the dye-containing medium with a clear, pre-warmed buffer. Allow the dye to equilibrate for 10-15 minutes.

- Image Acquisition: Capture images using a fluorescence microscope with appropriate filter sets.

- For TMRM, use excitation/emission ~548/573 nm. The intensity correlates with ΔΨm.

- For JC-1, acquire both green (ex/em ~514/529 nm) and red (ex/em ~585/590 nm) channels. Calculate the red/green fluorescence intensity ratio.

- Validation (Critical Control): At the end of the experiment, add an uncoupler like FCCP (1-10 µM) to fully dissipate ΔΨm. The subsequent loss of TMRM intensity or JC-1 red/green ratio confirms the signal is ΔΨm-dependent.

Protocol: Isolating Proton Pump Defects with Seahorse XF Analyzer

This protocol uses metabolic inhibitors to pinpoint which proton pump is dysfunctional.

- Principle: The Seahorse XF Analyzer measures the Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR), which is directly linked to proton pumping. Sequential injection of specific inhibitors allows for the dissection of ETC function [9].

- Workflow:

- Basal OCR: Measure the baseline OCR.

- ATP Synthase Inhibition: Inject oligomycin (1-2 µM). This inhibits ATP synthase, causing a drop in OCR. The remaining OCR is associated with proton leak.

- Uncoupling: Inject FCCP (0.5-2 µM). This uncouples electron transport from ATP synthesis, allowing maximum electron flux and OCR. A low response to FCCP suggests a defect in the proton-pumping complexes (I, III, IV) themselves.

- ETC Shutdown: Inject a cocktail of rotenone (Complex I inhibitor, 0.5-1 µM) and antimycin A (Complex III inhibitor, 1-2 µM). This shuts down all mitochondrial respiration, revealing the non-mitochondrial OCR.

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for ETC Functional Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Investigating ΔΨm and ETC Function

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function / Target | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Rotenone | Inhibits Complex I (IQ site) [8] | Used to isolate electron flow through Complex II; can increase ROS production at Complex I [8]. |

| Antimycin A | Inhibits Complex III (QI site) [7] | Blocks the Q-cycle, inducing significant ROS production at Complex III [7] [8]. |

| Cyanide (NaCN) | Inhibits Complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) [7] | Used to fully inhibit mitochondrial respiration and confirm the specificity of ΔΨm signals. |

| Oligomycin | Inhibits ATP synthase (Complex V) [9] | Used to distinguish between ATP-linked respiration and proton leak; prevents reverse activity of ATP synthase [1]. |

| FCCP | Chemical uncoupler [9] | Dissipates the proton gradient, uncoupling electron transport from ATP synthesis to measure maximum respiratory capacity. |

| TMRM / TMRE | ΔΨm-sensitive fluorescent dyes [11] [10] [9] | Quantitative measurement of ΔΨm in live cells via fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry. |

| JC-1 | Ratiometric ΔΨm-sensitive dye [11] | Provides a qualitative and semi-quantitative measure of ΔΨm via a shift in fluorescence emission (green/red ratio). |

| MitoTEMPO | Mitochondria-targeted superoxide scavenger [8] | Used to investigate the role of mitochondrial ROS in signaling and pathology. |

Advanced Technical Notes: Spatial Gradients and Cancer Research Implications

Recent research using super-resolution microscopy (e.g., STED, SIM) has revealed that the ΔΨm is not uniform across the inner mitochondrial membrane. The membrane potential of the cristae (ΔΨC), where the proton pumps are located, is higher (more negative) than that of the inner boundary membrane (ΔΨIBM) [10]. The cristae junction acts as a barrier that maintains this gradient. Methods have been developed to analyze this spatial membrane potential gradient (SMPG) by examining the distribution of TMRM fluorescence intensity relative to a reference stain like MitoTracker Green [10]. This is crucial for understanding how local ΔΨm changes, for instance, in response to calcium signals that hyperpolarize the cristae to boost ATP production [10].

Furthermore, the ETC and ΔΨm are emerging as important targets in disease research, particularly in cancer. Mutations in genes like DNMT3A can lead to DNA hypomethylation and increased expression of ETC components and supercomplex machinery (e.g., Cox7a2l) [9]. This results in elevated ΔΨm and mitochondrial respiration, which can confer a selective growth advantage to certain cells, such as in clonal hematopoiesis [9]. This elevated ΔΨm can also be a therapeutic vulnerability, as cells become more dependent on oxidative phosphorylation and more sensitive to targeted agents like MitoQ [9].

Contributions of ΔΨm and ΔpH to the Total Proton Motive Force (Δp)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the protonmotive force (Δp) and what are its components? The protonmotive force (Δp or pmF) is an electrochemical potential gradient across the mitochondrial inner membrane that serves as the central intermediate coupling electron transport to ATP synthesis. It is composed of two distinct components: the electrical potential gradient (ΔΨm) resulting from charge separation, and the chemical potential gradient (ΔpH) resulting from a difference in proton concentration across the membrane [12] [2].

FAQ 2: What are the typical relative contributions of ΔΨm and ΔpH to the total Δp under physiological conditions? Under most physiological conditions, the membrane potential (ΔΨm) is the dominant component, contributing approximately 75-85% of the total protonmotive force. The pH gradient (ΔpH) typically contributes the remaining 15-25% [2] [13]. For a typical total Δp of 200 mV, ΔΨm accounts for about 160-170 mV, while ΔpH contributes ~30-40 mV.

FAQ 3: Why might I measure a low ΔpH contribution in my experiments? A very low measured ΔpH (< 3 mV) can result from specific experimental conditions, including the use of certain phosphate concentrations or particular cell types [13]. Methodological factors are also critical: the use of high concentrations of potentiometric dyes like TMRM can saturate the cristae membranes and obscure the true ΔpH contribution. Using lower dye concentrations (e.g., 1.35-5.4 nM) is essential for accurate resolution of the ΔpH component [10].

FAQ 4: How does mitochondrial membrane architecture influence ΔΨm and ΔpH measurements? The inner mitochondrial membrane is not uniform. The cristae membranes (CM), which house the proton pumps, can maintain a different membrane potential (ΔΨC) compared to the inner boundary membranes (IBM, ΔΨIBM). The narrow cristae junctions act as barriers that can separate these potentials. This compartmentalization means that the ΔΨm you measure is often an average value, and local gradients can significantly impact bioenergetics and signaling [10].

FAQ 5: My data shows a change in ΔΨm. Can I directly conclude that the total protonmotive force has changed in the same way? Not always. While ΔΨm is the major component and often mirrors changes in the total Δp, the ΔpH component can change independently. For example, activation of ion exchangers or changes in matrix buffering capacity can cause a shift in the balance between ΔΨm and ΔpH without an immediate change in the total Δp. Therefore, for a complete picture, it is preferable to assess both components [12] [13].

Table 1: Typical Values and Contributions of ΔΨm and ΔpH to the Total Protonmotive Force

| Parameter | Typical Value | Contribution to Total Δp | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Δp | 170 - 200 mV | 100% | Value can change with energy demand and substrate availability [2] [13]. |

| ΔΨm (Electrical) | ~160 to -180 mV | ~80% (75-85%) | Dominant component; easily measured with potentiometric dyes [2] [14]. |

| ΔpH (Chemical) | ~0.4 pH units (~30 mV) | ~20% (15-25%) | Corresponds to a 2.5-fold difference in [H+]; often underestimated [2]. |

Table 2: Impact of Experimental Conditions on ΔΨm/ΔpH Balance

| Condition / Intervention | Effect on ΔΨm | Effect on ΔpH | Net Effect on Δp | Primary Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High ATP Demand (State 3) | Decrease | Decrease | Decrease | Increased H+ influx via ATP synthase consumes Δp [14]. |

| Oligomycin (ATP Synthase Inhibitor) | Increase | Variable | Increase (initially) | Block of main H+ consumption pathway; Δp builds up [14]. |

| Potassium Ionophores (e.g., VCP) | Decrease | Increase | Variable | K+/H+ exchange dissipates ΔΨm but can enhance ΔpH [13]. |

| Calcium Influx into Matrix | Increase (in Cristae) | Variable | Increase | Boosts TCA cycle & ETC activity, increasing H+ pumping [10]. |

| Mild Uncoupling (FCCP, low dose) | Decrease | Decrease | Decrease | Induces H+ leak, dissipating both components [15]. |

Experimental Protocols & Troubleshooting

Protocol: Measuring Spatial Membrane Potential Gradients with TMRM/MTG

Objective: To resolve distinct membrane potentials between the cristae membranes (CM) and inner boundary membranes (IBM) in living cells.

Principle: This method uses SIM super-resolution microscopy and the differential, concentration-dependent accumulation of two dyes: potential-sensitive TMRM and potential-insensitive MitoTracker Green (MTG), which serves as a morphological reference [10].

Workflow:

- Cell Staining: Incubate cells with 500 nM MitoTracker Green (MTG) and a low concentration of TMRM (1.35 - 5.4 nM) for 30 minutes. Using low TMRM is critical to avoid saturation and reveal the true gradient.

- Image Acquisition: Perform simultaneous dual-channel imaging using Structured Illumination Microscopy (SIM).

- Data Analysis (IBM Association Index):

- Use the MTG channel to define the mitochondrial boundaries automatically (e.g., using Otsu's thresholding).

- Generate two regions of interest (ROIs): a shrunken region for the Cristae (CM) and a widened region for the Inner Boundary Membrane (IBM).

- Calculate the IBM Association Index = (Mean TMRM intensity in IBM ROI) / (Mean TMRM intensity in CM ROI). A lower index indicates a higher relative potential in the cristae [10].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: No gradient detected, uniform TMRM signal. Solution: Confirm the use of low TMRM concentrations (1.35-5.4 nM). High dye concentrations saturate the cristae and mask the gradient. Verify SIM resolution and calibration [10].

- Problem: Poor signal-to-noise ratio in TMRM channel. Solution: Optimize dye loading time and temperature. Ensure minimal photobleaching by using low illumination intensities.

- Problem: Histamine stimulation does not induce the expected hyperpolarization in cristae. Solution: Validate ER calcium stores and mitochondrial calcium uptake pathways. Confirm activity of complexes I and III, as this response depends on proton pump activity [10].

Protocol: Computational Modeling of ΔΨm/ΔpH Contribution

Objective: To simulate how ion transport mechanisms control the balance between ΔΨm and ΔpH.

Principle: Computer models of oxidative phosphorylation can be extended to include key ion transport processes—K+ uniport, K+/H+ exchange, and membrane capacitance—to predict how the ΔΨm/ΔpH ratio changes under various conditions [13].

Workflow:

- Model Framework: Utilize an established model of oxidative phosphorylation (e.g., Korzeniewski model).

- Define Key Equations:

- K+ Uniport (vKuni): Dependent on the membrane potential (ΔΨm) and intra-/extramitochondrial K+ concentration.

- K+/H+ Exchange (vKHex): Dependent on the K+ and H+ gradients across the membrane.

- Membrane Capacitance: Describes how charge separation builds ΔΨm.

- Parameterization: Set initial rate constants (e.g., kKuni, kKHex), ion concentrations, and buffering capacities based on experimental data.

- Simulation & Validation: Run simulations under different conditions (e.g., varying ATP demand, inhibitor presence) and validate the output against empirical measurements of ΔΨm and ΔpH [13].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Model predicts an unphysiologically low ΔpH (e.g., < 3 mV). Solution: Re-evaluate the ratio of the rate constants for K+ uniport and K+/H+ exchange. The contribution of ΔΨ and ΔpH is determined by the ratio of these constants, not their absolute values [13].

- Problem: Model is unstable or fails to converge. Solution: Check the initial conditions and ensure the differential equations for H+ and K+ transport are correctly implemented, including the buffering coefficients for the matrix and cytosol.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Δp Components

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Considerations for ΔΨm/ΔpH Studies |

|---|---|---|

| TMRM / TMRE | Potentiometric dye for measuring ΔΨm. | Critical: Use low concentrations (1.35-5.4 nM) to resolve spatial gradients between CM and IBM. High concentrations saturate the signal [10]. |

| MitoTracker Green (MTG) | Mitochondrial morphology dye; stains IMM independent of potential. | Used as a spatial reference marker in super-resolution studies to normalize TMRM distribution [10]. |

| Oligomycin | Inhibitor of ATP synthase (Complex V). | Used to block the primary consumer of Δp. Causes a buildup of Δp, useful for assessing ETC pumping capacity [14]. |

| FCCP / CCP | Chemical uncoupler; carries protons across IMM. | Dissipates both ΔΨm and ΔpH. Low doses can induce "mild uncoupling" to test ROS sensitivity [15]. |

| Rotenone & Antimycin A | Inhibitors of ETC Complex I and III. | Reduce Δp generation. Useful to confirm that Δp changes are linked to proton pump activity [10]. |

| K+/H+ Exchanger Ionophores (e.g., nigericin) | Collapses ΔpH by exchanging K+ for H+. | Used to dissect the individual contributions of ΔΨm and ΔpH to the total Δp or to a specific process. |

| MitoSNARE-ATeam / mt-MaLion | Genetically encoded sensors for matrix ATP:ADP ratio or pH. | Provide an indirect readout of Δp activity and allow compartment-specific measurement of the ΔpH component. |

ΔΨm as a Key Indicator of Mitochondrial Health and Cellular Viability

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is ΔΨm and why is it a key indicator of mitochondrial health?

The mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) is the electrical potential difference across the inner mitochondrial membrane, generated by the proton pumps of the electron transport chain (Complexes I, III, and IV). It is an essential component in the process of energy storage during oxidative phosphorylation. Together with the proton gradient (ΔpH), ΔΨm forms the transmembrane potential of hydrogen ions which is harnessed by ATP synthase to produce ATP [1].

ΔΨm serves not only for ATP synthesis but is also a critical factor in determining mitochondrial viability by participating in the elimination of dysfunctional mitochondria (mitophagy). Furthermore, it acts as a driving force for the transport of charged ions (such as Ca2+ and Fe2+) and proteins that are necessary for healthy mitochondrial function. Sustained changes in ΔΨm can be deleterious, with prolonged drops or rises from normal levels potentially inducing loss of cell viability and contributing to various pathologies [1].

Q2: What are the typical physiological values of ΔΨm in healthy cells?

In healthy, active mitochondria, the membrane potential typically ranges from -150 mV to -180 mV [16]. Quantitative measurements in specific cell types, such as cultured rat cortical neurons, have shown a resting ΔΨm of approximately -139 mV, which can be regulated between -108 mV and -158 mV in response to changes in energy demand and metabolic activation [17]. It is noteworthy that ΔΨm in intact cells is generally smaller (e.g., -120 mV to -160 mV) compared to that observed in isolated mitochondria suspended in artificial media (-180 mV to -190 mV) [17].

Q3: My ΔΨm measurements are inconsistent. What could be causing this?

Inconsistencies in ΔΨm measurements can arise from numerous sources. The table below summarizes common artifacts and their solutions.

Table: Troubleshooting Common ΔΨm Measurement Artifacts

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High background fluorescence/noise | Non-specific probe binding; dye aggregation; cellular autofluorescence [17]. | Titrate dye concentration; include proper wash steps; use probes with low background (e.g., LDS 698) [16]. |

| False depolarization readings | Probe overloading leading to quenching artifacts; inappropriate use of non-Nernstian dyes (e.g., JC-1 aggregates) [17]. | Use low, non-quenching dye concentrations; validate with a Nernstian dye like TMRM in non-quench mode [17]. |

| Variable results between cell types | Differences in plasma membrane potential (ΔΨP), mitochondrial density, cell size, and volume ratios [17]. | Use a calibration paradigm that accounts for ΔΨP, volume ratios, and binding properties [17]. |

| Dye leakage or sequestration | Probe instability; metabolism of the dye; active export from cells [18]. | Use esterase-resistant probes where possible; perform time-course experiments to monitor signal stability. |

| Unresponsive ΔΨm signal | Use of covalent trappers (e.g., MitoTracker Red FM) that do not reflect dynamic changes [16]. | Switch to reversible, equilibrium-distribution probes like TMRM or LDS 698 for real-time tracking [16]. |

Q4: How do I choose the right fluorescent probe for my ΔΨm experiment?

The choice of probe depends on your experimental goals, required sensitivity, and the equipment available. Key considerations include the need for quantitative vs. qualitative data, the expected magnitude of ΔΨm changes, and the potential for artifacts.

Table: Comparison of Common Fluorescent Probes for ΔΨm Measurement

| Probe Name | Measurement Mode | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMRM / TMRE | Reversible, Nernstian distribution [17]. | Suitable for quantitative, absolute measurements; can be used in quench or non-quench mode [17]. | Signal depends on ΔΨP, volume ratios, and binding; requires careful calibration [17]. | Quantitative tracking of kinetics and absolute values of ΔΨm [17]. |

| JC-1 | Ratiometric (shift from green monomer to red J-aggregates) [16]. | Visual and ratiometric output; easy to interpret polarization. | Prone to non-specific staining; aggregation influenced by factors other than ΔΨm; non-equilibrium distribution [16]. | Qualitative assessment of large shifts in polarization. |

| MitoTracker Red FM | Covalent binding (irreversible) [16]. | Good for fixed cells and tracking mitochondrial morphology. | Does not respond to subsequent changes in ΔΨm after loading [16]. | End-point experiments requiring fixation. |

| LDS 698 | Reversible, Nernstian distribution [16]. | High sensitivity to subtle changes; low background fluorescence; tracks kinetics effectively [16]. | Less commonly used; validation history is shorter than TMRM. | Detecting fine, transient changes in ΔΨm in live cells [16]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents and Tools for ΔΨm Research

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Principle | Example Use in Experimentation |

|---|---|---|

| Tetramethylrhodamine Methyl Ester (TMRM) | Cationic, lipophilic dye that distributes across membranes according to the Nernst equation [17]. | Quantitative imaging of ΔΨm dynamics in live cells under different metabolic conditions. |

| LDS 698 | Hemicyanine dye with low background, high sensitivity for detecting subtle ΔΨm changes [16]. | Tracking kinetics of slight depolarizations or hyperpolarizations that may be missed by other dyes. |

| Carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP) | Protonophore uncoupler that dissipates the proton motive force, collapsing ΔΨm [17]. | Used as a control to induce maximal depolarization and validate probe response. |

| Oligomycin | ATP synthase inhibitor [1]. | Used to block ATP synthesis, allowing assessment of ΔΨm dependent on proton leak and respiratory chain activity. |

| Nigericin | K+/H+ exchanger ionophore [19]. | Used to dissect the components of the proton motive force by collapsing ΔpH, leading to a compensatory hyperpolarization of ΔΨm. |

| Valinomycin | K+ ionophore [19]. | Used to dissect the proton motive force by hyperpolarizing the plasma membrane or, under specific conditions in isolated mitochondria, to manipulate ΔΨm and ΔpH independently. |

| ATPase Inhibitory Factor 1 (IF1) | Endogenous protein that inhibits the reverse activity of ATP synthase (ATP hydrolysis) [1]. | Studied to understand how cells prevent wasteful ATP hydrolysis to maintain ΔΨm during stress. |

Experimental Protocols for Quantitative ΔΨm Assessment

Protocol 1: Absolute Quantification of ΔΨm in Adherent Cells using TMRM

This protocol, adapted from [17], allows for the measurement of absolute ΔΨm values in millivolts.

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

Cell Preparation and Dye Loading:

- Culture adherent cells (e.g., primary neurons) on poly-ornithine-coated coverglasses or chambered coverglasses.

- Load cells with a low concentration (e.g., 10-50 nM) of TMRM in non-quench mode to avoid artifacts from dye aggregation and quenching. Simultaneously, load cells with a bis-oxonol-type plasma membrane potential (ΔΨP) indicator (PMPI) to monitor and account for changes in plasma membrane potential.

Fluorescence Imaging:

- Perform time-lapse fluorescence imaging using an appropriate microscope setup. Acquire images for TMRM and PMPI fluorescence.

- At the end of the experiment, apply a calibration paradigm. This typically involves sequential additions of:

- Oligomycin (1 µg/mL): To inhibit ATP synthase and observe ΔΨm under non-phosphorylating conditions.

- FCCP (1-2 µM): To completely collapse ΔΨm and obtain a minimum fluorescence value.

Data Analysis and Deconvolution:

- Use a biophysical model that accounts for the Nernstian distribution of TMRM, ΔΨP-dependent probe dynamics, mitochondrial and cellular volume ratios, and high- and low-affinity dye binding [17].

- Input the fluorescence time courses, calibration parameters, and volume data into a mathematical algorithm (e.g., compatible with spreadsheet calculations or custom software) to deconvolute the absolute values of ΔΨP and ΔΨM in millivolts over time.

Protocol 2: Assessing Subtle ΔΨm Changes with LDS 698

This protocol leverages the high sensitivity of LDS 698 to detect fine variations in membrane potential [16].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

Dye Loading:

- Incubate live cells with LDS 698 at a concentration of approximately 1 µM in the culture medium for 15-30 minutes at 37°C.

- Replace the dye-containing medium with a fresh, pre-warmed buffer to remove excess, unincorporated dye.

Fluorescence Measurement:

- Acquire fluorescence using excitation at ~460 nm and collect emission in the 580-700 nm range. LDS 698 exhibits weak fluorescence in its free state, leading to low background, and its fluorescence increases upon accumulation in mitochondria [16].

- Fluorescence can be monitored via fluorescence microscopy, flow cytometry, or a plate reader.

Experimental Treatment and Validation:

- Expose the cells to the experimental condition of interest (e.g., a drug, metabolic stressor).

- Track the fluorescence kinetics over time. The high sensitivity of LDS 698 allows for the detection of even faint changes in ΔΨm.

- Confirm that the fluorescence changes are ΔΨm-dependent by adding an uncoupler like FCCP at the end of the experiment to collapse the potential.

Advanced Topic: The Interplay between ΔΨm, ΔpH, and Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production

The proton motive force (pmf) driving ATP synthesis comprises both ΔΨm and the pH gradient (ΔpH). Understanding their relationship is crucial, especially in pathological contexts like ischemia-reperfusion injury, where reverse electron transport (RET) at Complex I is a major source of damaging ROS [19].

Key Findings:

- ΔΨm is Dominant: Research indicates that succinate-driven RET-evoked ROS production is more dependent on ΔΨm than on ΔpH. A minor decrease in ΔΨm can lead to a significant suppression of ROS generation [19].

- Absolute pH Matters: The absolute intramitochondrial pH (pHin), rather than the ΔpH value itself, also modulates the rate of ROS formation during RET [19].

- Experimental Dissection: The ionophores nigericin (a K+/H+ exchanger, which decreases ΔpH and hyperpolarizes ΔΨm) and valinomycin (a K+ ionophore, which can depolarize ΔΨm and increase pHin) are critical tools for dissecting the individual contributions of ΔΨm and ΔpH to ROS production [19].

Pathway and Experimental Logic:

Troubleshooting Common ΔΨm Measurement Issues

Q: My readings for mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) are inconsistent and vary between technical replicates. What could be causing this?

Inconsistent ΔΨm readings often stem from improper dye handling or concentration issues. The cationic fluorescent dyes used to measure ΔΨm (such as TMRE and JC-1) are sensitive to experimental conditions. Ensure you are using the optimal dye concentration for your specific cell type, as excessive dye can lead to self-quenching, while insufficient dye yields weak signals. Always prepare fresh dye working solutions and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles of stock solutions. Furthermore, maintain consistent loading times and temperatures across all replicates, as these factors significantly impact dye uptake and distribution [20].

Q: I observe high background fluorescence in my ΔΨm assays. How can I reduce this?

High background fluorescence typically results from incomplete removal of unincorporated dye or non-specific binding. After the dye loading incubation, perform multiple careful washes with a dye-free buffer. Including a small amount of bovine serum albumin (BSA, 0.1-0.5%) in the wash buffer can help scavenge residual dye. For adherent cells, consider gentle agitation during washing. Additionally, verify that your instrument's optical settings (exposure time, gain) are calibrated using an unstained control, and subtract this background from your experimental readings [20].

Q: My pharmacological controls for uncouplers (like FCCP) are not giving the expected depolarization. What might be wrong?

If the expected depolarization with uncouplers is not observed, first verify the preparation and storage of your uncoupler stock solution. FCCP, for instance, should be dissolved in high-quality DMSO or ethanol and stored at -20°C, protected from light and moisture. Check the final working concentration, as too little may be insufficient, while too much can be toxic. A final concentration of 2-5 µM FCCP is commonly used. Also, ensure adequate incubation time (typically 5-15 minutes) for the uncoupler to take full effect before reading. Pre-warm the uncoupler solution to the assay temperature to facilitate rapid action [20] [9].

Optimizing Experimental Conditions for ΔΨm Research

Q: How does the cellular growth medium affect my ΔΨm measurements?

The composition of your growth medium can significantly influence mitochondrial physiology. High concentrations of glucose (e.g., in DMEM) can promote glycolysis, potentially masking mitochondrial phenotypes. Media containing pyruvate can help maintain mitochondrial function. For consistent results, use a well-buffered, nutrient-replete medium, and ensure the pH is stable (typically 7.4) throughout the experiment, as intracellular and mitochondrial pH are tightly linked to membrane potential. It is good practice to measure ΔΨm in a controlled, physiological buffer (e.g., Krebs-Ringer buffer) after replacing the growth medium to minimize confounding factors [21] [22].

Q: My cell line has a very high glycolytic rate. How can I ensure I'm measuring a true ΔΨm signal?

In highly glycolytic cells, mitochondria may be less active, and ΔΨm can be lower. To confirm that your signal is specific to the mitochondrial potential, include a positive control using a mitochondrial substrate like succinate (for complex II) or pyruvate/malate (for complex I) to energize the mitochondria and observe a hyperpolarization. Conversely, the uncoupler control (e.g., FCCP) should collapse the potential. Comparing the signal with and without these modulators confirms that the fluorescence shift is due to changes in ΔΨm and not other non-specific factors [20] [23].

Q: What is the best way to isolate primary cells for ΔΨm studies without damaging their native state?

The isolation procedure for primary cells is critical. Use gentle, optimized dissociation protocols to minimize physical and metabolic stress. Keep samples on ice or at 4°C during processing when possible, and use isolation buffers that are calcium-free and contain chelators (like EDTA/EGTA) to prevent premature activation. Crucially, allow a sufficient "recovery" period (at least 1-2 hours) in complete, nutrient-rich media at 37°C after isolation and before staining for ΔΨm. This allows the cells to restore ion gradients and recover from the isolation stress, providing a more accurate reflection of their in vivo state [9].

Data Interpretation and Contextualization

Q: I've found that my experimental treatment increases ΔΨm. Is this beneficial or detrimental to the cell?

An elevated ΔΨm can be a double-edged sword, and context is key. A moderately high ΔΨm can indicate a metabolically active, efficient oxidative phosphorylation system, supporting higher ATP production. However, an excessively high ΔΨm is a known risk factor for increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production because it can increase electron leak from the electron transport chain (ETC). You must correlate your finding with other measurements. Assess mitochondrial ROS production, cellular health (e.g., viability assays), and functional output (e.g., ATP levels). A concurrent rise in ROS and signs of stress suggest the hyperpolarization is pathological [9] [23].

Q: How do I distinguish between a primary defect in ΔΨm and a secondary effect from another cellular process?

Mitochondrial membrane potential is a integrative parameter influenced by many processes. To pinpoint a primary defect, a multi-faceted approach is necessary. Probe the ETC directly by measuring oxygen consumption rates (OCR) in the presence of specific inhibitors (using a Seahorse Analyzer or similar platform). Assess the proton gradient's other component, ΔpH, if possible. Also, check for upstream issues such as changes in substrate availability, TCA cycle function, or adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT) activity. A primary defect in ΔΨm maintenance will typically show direct abnormalities in ETC function or coupling, while secondary effects may present with normal ETC function but altered substrate flux or ATP demand [22] [23].

Q: In my disease model, ΔΨm is low. Does this automatically mean ATP depletion and cell death?

Not necessarily. A reduced ΔΨm indicates lower proton motive force, which can diminish the rate of ATP synthesis. However, cells can adapt. They may upregulate glycolysis to compensate for reduced mitochondrial ATP production. Measure the actual ATP/ADP ratio and lactate production to understand the metabolic shift. Furthermore, a mild, chronic reduction in ΔΨm can be an adaptive mechanism to lower ROS production and minimize oxidative damage, as seen in some models of metabolic stress. Correlate the low ΔΨm with long-term cell survival and overall function to determine its pathological significance [24] [23].

Quantitative Data Reference Tables

Table 1: Physiological and Pathological Ranges of Key Mitochondrial Parameters

| Parameter | Physiological Range | Pathological Indication | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytosolic H₂O₂ [24] | ~80 nM | >100 nM (Distress) | Genetically encoded sensors (e.g., roGFP) |

| Mitochondrial Matrix H₂O₂ [24] | 5-20 nM | Sustained elevation | Genetically encoded sensors |

| ER Lumen H₂O₂ [24] | ~700 nM | Disruption to prot. folding | Genetically encoded sensors |

| GSH/GSSG Ratio (Cytosol) [24] | High (e.g., 100:1) | Low (e.g., <10:1) | Enzymatic recycling assay / fluorescent probes |

| ΔΨm (High vs Low) [9] | Context-dependent | Excessively high ΔΨm linked to increased ROS & pathology | TMRE, JC-1, TMRM staining |

Table 2: Common Pharmacological Agents for Modulating and Studying ΔΨm

| Agent | Primary Target | Effect on ΔΨm | Typical Working Concentration | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCCP [20] | Protonophore (uncoupler) | ↓ Depolarization | 1-5 µM | Complete depolarization control; requires solvent control (DMSO). |

| Oligomycin [9] | ATP synthase (Complex V) | ↑ Hyperpolarization | 1-10 µM | Inhibits ATP synthesis, reduces proton consumption, increases ΔΨm. |

| MitoQ [9] | Mitochondrial ROS | Context-dependent | 100-500 nM | A mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant; its TPP+ cation accumulation depends on ΔΨm. |

| Antimycin A | Complex III | ↓ Depolarization | 1-10 µM | Inhibits ETC, increases superoxide production. |

| Rotenone | Complex I | ↓ Depolarization | 100-500 nM | Inhibits ETC; can induce complex I-dependent ROS. |

Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Precise Measurement of ΔΨm using TMRE Staining and Flow Cytometry

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to identify HSPCs with elevated ΔΨm [9].

- Cell Preparation: Harvest and wash cells in a suitable buffer (e.g., PBS or a physiological salt solution). For adherent cells, use a gentle, non-enzymatic dissociation method if possible to preserve surface receptors and mitochondrial integrity.

- Dye Loading: Resuspend cells at a density of 1-2 x 10^6 cells/mL in pre-warmed culture medium or assay buffer containing 20-100 nM TMRE. The optimal concentration should be determined empirically for each cell type.

- Incubation: Incubate the cells for 15-30 minutes at 37°C in the dark to allow for dye uptake and distribution.

- Washing: Pellet the cells and wash twice with a large volume (e.g., 5x the staining volume) of TMRE-free, pre-warmed buffer to remove extracellular dye.

- Control Preparation:

- Unstained Control: A sample of cells not exposed to TMRE.

- FCCP Control: A sample stained with TMRE in the presence of 2-5 µM FCCP during the incubation and washing steps. This sample defines the background/depolarized fluorescence.

- Flow Cytometry: Resuspend the cells in a small volume of fresh buffer and analyze immediately on a flow cytometer. Use the FL2 (PE) channel or its equivalent. Acquire at least 10,000 events per sample. The median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the TMRE-stained sample (minus the FCCP control MFI) is proportional to the ΔΨm.

Protocol 2: Assessing Coupling Efficiency and ROS Relationship using SCENITH

This method, based on the SCENITH assay, allows for the determination of metabolic dependencies [9].

- Plate Cells: Seed cells in a 96-well plate at a uniform density.

- Metabolic Inhibition: Treat cells with different metabolic inhibitors for a defined period (e.g., 1-2 hours). Key treatments include:

- DMSO: Vehicle control.

- Oligomycin (1-10 µM): To inhibit mitochondrial ATP synthase (OXPHOS inhibition).

- 2-DG (50mM) + Oligomycin: To inhibit both glycolysis and OXPHOS (global energy inhibition).

- FCCP (2-5 µM): To uncouple mitochondria and induce maximum respiration.

- Puromycin Incorporation: Add puromycin (1-10 µM) to the culture medium for the final 10-30 minutes of the inhibition period. Puromycin incorporates into newly synthesized polypeptides, and its level serves as a proxy for global protein translation, which is a major energy-consuming process.

- Fixation and Staining: Fix the cells, permeabilize, and stain intracellularly with an anti-puromycin antibody.

- Flow Cytometry and Analysis: Analyze puromycin incorporation by flow cytometry. The decrease in protein translation upon oligomycin treatment, relative to the DMSO control, indicates the cell's dependence on mitochondrial OXPHOS for energy. A greater inhibition in your experimental group suggests a higher reliance on mitochondrial respiration, which is often linked to a high ΔΨm [9].

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: The ΔΨm Balancing Act

Diagram 2: Hyperpolarization Investigation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for ΔΨm and Redox Research

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Key Application in ΔΨm Research |

|---|---|---|

| TMRE / TMRM [20] [9] | Cationic, fluorescent ΔΨm probe. | Quantitative measurement of ΔΨm via fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry. Accumulates in the mitochondrial matrix in a potential-dependent manner. |

| JC-1 [20] | Ratiometric ΔΨm probe. | Distinguishes healthy (red J-aggregates) from depolarized (green monomers) mitochondria, providing an internal ratio. |

| FCCP [20] | Protonophore uncoupler. | Positive control for complete mitochondrial depolarization; validates that a fluorescent signal is ΔΨm-dependent. |

| MitoSOX Red | Mitochondrial superoxide indicator. | Directly measures the primary ROS (superoxide) produced in the mitochondria, often a consequence of high ΔΨm. |

| MitoQ [9] | Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant. | A tool to dissect the role of mitochondrial ROS in a phenotype. Its TPP+ moiety drives accumulation based on ΔΨm. |

| Oligomycin [9] | ATP synthase inhibitor. | Used to probe coupling efficiency. Induces a hyperpolarization by preventing proton re-entry via ATP synthase. |

| Genetic ΔΨm Biosensors (e.g., mt-cpYFP) [25] | Report on mitochondrial pH and electrical pulses. | Used to detect subtle, transient changes in mitochondrial energetics ("mitoflashes") linked to matrix pH and ΔΨm. |

| GSH/GSSG-Glo Assay | Measures glutathione redox potential. | Quantifies the major cellular antioxidant buffer, providing context for the level of oxidative distress caused by high-ΔΨm-driven ROS [24]. |

FAQ: Fundamental Concepts and Disease Links

F1: What are ΔΨm and ΔpH, and why are they critical for mitochondrial function? The mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) and the proton gradient (ΔpH) are the two components that make up the proton electrochemical gradient, or proton motive force, across the inner mitochondrial membrane. This gradient is generated by the respiratory chain and accounts for over 90% of the energy available for respiration, driving the production of ATP. ΔΨm, the electric potential component, is particularly reflective of the functional metabolic status of mitochondria [26].

F2: How does the dysregulation of ΔΨm/ΔpH contribute to neurodegenerative diseases? Mitochondrial dysfunction, including the collapse of ΔΨm, is a central mechanism in chronic neurodegenerative diseases. It directly leads to insufficient energy (ATP) for neurons, impairing neurotransmitter synthesis and release. This dysfunction also triggers increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and disrupts calcium homeostasis, creating a vicious cycle that promotes neuroinflammation and neuronal cell death, which are hallmarks of diseases like Alzheimer's (AD) and Parkinson's (PD) [27] [28].

F3: What is the connection between ΔΨm/ΔpH impairment and metabolic diseases like Type 2 Diabetes? Recent research has uncovered a specific mechanism in obesity where defective coenzyme Q metabolism in the liver drives a process called reverse electron transport (RET) at mitochondrial complex I. This leads to excessive, site-specific production of mitochondrial ROS (mROS), which disrupts metabolic homeostasis and is a key factor in driving insulin resistance and the development of Type 2 Diabetes [29].

F4: What are the primary experimental methods for assessing ΔΨm in live cells and isolated mitochondria? The two primary methodological approaches are:

- Electrochemical Probes: Using a tetraphenylphosphonium (TPP+)-selective electrode to measure the accumulation of this cationic probe in isolated mitochondria [26].

- Fluorometric Evaluations: Using fluorescent, cationic dyes like tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) in conjunction with instruments such as microplate readers or flow cytometers to assess ΔΨm in both isolated mitochondria and live cells [26].

F5: Beyond an energy deficit, what other pathological pathways are activated by a loss of ΔΨm? The collapse of ΔΨm is now understood to trigger broader mitochondrial stress responses. This includes the activation of the mitochondrial integrated stress response (mt-ISR) at the molecular level and alterations in mitochondrial dynamics (fusion/fission) at the organelle level. Ultimately, severe or sustained dysfunction can initiate programmed cell death pathways (apoptosis) [28].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

T1: Problem: High background noise and inconsistent results when measuring ΔΨm with potentiometric dyes (e.g., TMRM).

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect dye loading or concentration. | Titrate dye concentration; verify loading temperature and time. | Optimize dye loading protocol for your specific cell type; use the minimum dye concentration required for a clear signal. |

| Dye sequestration or compartmentalization. | Check for punctate staining patterns unrelated to mitochondria. | Use a lower dye concentration and shorter incubation time; consider using alternative dyes less prone to sequestration. |

| Uncompensated plasma membrane potential (ΔΨp). | Use a pharmacological agent to depolarize the plasma membrane and assess its contribution. | Include an agent like gramicidin to clamp the plasma membrane potential and ensure the signal is specific to ΔΨm. |

| Cell death or poor health. | Assess cell viability with a marker like propidium iodide alongside the potentiometric dye. | Ensure cultures are healthy and sub-confluent; avoid prolonged experimental timelines that induce stress. |

T2: Problem: Discrepancy between ΔΨm measurements and other markers of mitochondrial function (e.g., ATP levels).

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Compensatory glycolysis maintaining ATP. | Measure extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) as a proxy for glycolysis. | Interpret ΔΨm data in the context of overall cellular metabolism, as cells may compensate for OXPHOS defects by enhancing glycolysis [28]. |

| Uncoupling. The proton gradient is dissipated without ATP synthesis. | Measure oxygen consumption rate (OCR); uncouplers will increase OCR. | Treat with an uncoupler like FCCP as a control. A maintained ΔΨm in the face of low ATP suggests other pathologies. |

| Incomplete coupling or electron transport chain (ETC) inhibition. | Use specific ETC inhibitors (rotenone, antimycin A) to probe different sites. | Perform a mitochondrial stress test to dissect the specific site of dysfunction within the ETC. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents for Investigating ΔΨm/ΔpH and Mitochondrial Dysfunction

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function / Application | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Tetramethylrhodamine, Methyl Ester (TMRM) | Cationic, fluorescent dye used to measure ΔΨm in live cells via fluorometry or flow cytometry. Its accumulation in the mitochondrial matrix is proportional to ΔΨm [26]. | Load cells with 20-100 nM TMRM for 30 min at 37°C. Analyze via flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy. A decrease in fluorescence intensity indicates depolarization. |

| Tetraphenylphosphonium (TPP+) Electrode | Electrochemical probe for direct, quantitative measurement of ΔΨm in isolated mitochondrial preparations [26]. | Isolate mitochondria via differential centrifugation. Add TPP+ to the preparation and measure its accumulation using a TPP+-selective electrode. Calibrate with a known K+ gradient. |

| Carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP) | Proton ionophore that uncouples mitochondrial respiration by dissipating the proton gradient (ΔΨm and ΔpH). Serves as a critical control for depolarization. | In a TMRM assay, add 1-5 µM FCCP at the endpoint. A rapid loss of fluorescence confirms the signal was ΔΨm-dependent. |

| Rotenone | Specific inhibitor of mitochondrial Complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase). Used to induce ETC dysfunction and study subsequent ΔΨm collapse. | Pre-treat cells (e.g., 1 µM for 1-4 hours) to inhibit Complex I and model defects seen in Parkinson's disease and other disorders. |

| Idebenone | Synthetic analog of coenzyme Q10 that can shuttle electrons in the ETC. Used therapeutically and experimentally to bypass ETC blocks. | Apply to cell models of CoQ deficiency or RET-driven ROS production (e.g., 1-10 µM) to assess rescue of ΔΨm and reduction of oxidative stress [29] [28]. |

Experimental Protocols

P1: Protocol for Evaluating ΔΨm in Live Cells Using TMRM and Flow Cytometry

This protocol details a semi-quantitative method for assessing relative changes in ΔΨm across cell populations, ideal for screening treatments or modeling disease states.

Principle: The lipophilic, cationic dye TMRM accumulates in the mitochondrial matrix in a manner dependent on the highly negative ΔΨm. A depolarization (loss of ΔΨm) results in a loss of TMRM fluorescence.

Materials:

- Cell culture of interest

- TMRM stock solution (e.g., 1 mM in DMSO)

- Flow cytometry buffer (e.g., PBS with glucose)

- Control compounds: FCCP (50 µM stock in DMSO) or CCCP (for full depolarization)

- Flow cytometer with appropriate laser and filter (e.g., 488 nm excitation, 574 nm emission)

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest and wash cells. Adjust cell concentration to 1-2 x 10^6 cells/mL in flow cytometry buffer.

- Dye Loading: Incubate cells with a pre-optimized concentration of TMRM (typically 20-100 nM) for 30 minutes at 37°C in the dark.

- Experimental Controls:

- Unstained Control: Cells without TMRM.

- Fully Depolarized Control: Cells stained with TMRM and treated with 10-20 µM FCCP/CCCP for the final 5-10 minutes of incubation.

- Data Acquisition: Analyze the cells immediately on the flow cytometer. Collect a minimum of 10,000 events per sample.

- Data Analysis: Gate on viable cells based on forward and side scatter. Plot the fluorescence intensity of the TMRM channel (e.g., PE-Texas Red). The geometric mean fluorescence intensity (GeoMFI) is used for comparison. A decrease in GeoMFI relative to the untreated, stained control indicates a loss of ΔΨm.

P2: Protocol for Isolating Mitochondria and Assessing ΔΨm via TPP+-Selective Electrode

This method provides a direct, quantitative measurement of ΔΨm in a controlled, isolated system, free from cytosolic influences.

Principle: The TPP+ cation distributes across the inner mitochondrial membrane in response to ΔΨm. A TPP+-selective electrode detects the concentration of TPP+ in the extramitochondrial medium, which decreases as the probe is driven into the matrix by the negative potential.

Materials:

- Tissue or pelleted cells

- Mitochondrial isolation buffer (e.g., containing mannitol, sucrose, HEPES, EDTA)

- Respiration buffer (e.g., containing KCl, sucrose, HEPES, KH2PO4)

- TPP+ chloride stock solution

- Substrates: Succinate (for Complex II-driven respiration), Glutamate/Malate (for Complex I)

- Inhibitors/Uncouplers: Rotenone, FCCP

- TPP+-selective electrode and a voltmeter/data acquisition system

Procedure:

- Mitochondrial Isolation: Homogenize tissue or cells in ice-cold isolation buffer. Isolate mitochondria using standard differential centrifugation techniques.

- Electrode Calibration: Calibrate the TPP+-selective electrode by adding known amounts of TPP+ to the respiration buffer and recording the voltage response.

- Assay Setup: Add mitochondria (e.g., 0.5-1 mg protein) to respiration buffer in a stirred, temperature-controlled chamber (e.g., 37°C). Add a known quantity of TPP+.

- Measurement:

- Initiate respiration by adding a substrate (e.g., succinate).

- Record the voltage change as TPP+ is taken up by the mitochondria, causing a decrease in external [TPP+].

- The magnitude of the voltage change is proportional to the accumulated TPP+, which is related to ΔΨm.

- Add FCCP at the end to dissipate ΔΨm and release TPP+, confirming the signal specificity.

- Calculation: ΔΨm (in millivolts) can be calculated using the Nernst equation based on the measured internal and external TPP+ concentrations.

Signaling Pathways and Disease Mechanisms Visualization

Mechanisms Linking ΔΨm/ΔpH Impairment to Disease

Workflow for Live-Cell ΔΨm Assay

Advanced Tools and Techniques for Quantifying Membrane Potential and pH Dynamics

Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) is a key indicator of cellular health, serving as a critical parameter in the study of various diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders, cancer, and metabolic syndromes. The electrochemical proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane, comprising both ΔΨm and the mitochondrial pH gradient (ΔpHm), provides the driving force for ATP synthesis [30]. Cationic fluorescent dyes have become indispensable tools for monitoring ΔΨm in living cells, enabling researchers to assess mitochondrial function in real-time. These lipophilic cations accumulate in the mitochondrial matrix in a Nernstian fashion, inversely proportional to ΔΨm [30]. A more negative (polarized) ΔΨm accumulates more dye, while depolarization results in dye release. Understanding the principles, applications, and limitations of these probes is essential for proper experimental design and data interpretation in mitochondrial research, particularly when investigating complex bioenergetic phenomena where ΔΨm may not always correlate directly with proton gradient changes [30].

Dye Selection Guide: Comparative Profiles

Spectral Properties and Functional Characteristics

Table 1: Comparative characteristics of TMRM, Rhodamine 123, and JC-1

| Characteristic | TMRM | Rhodamine 123 | JC-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excitation/Emission (nm) | 550/576 [31] | 507/529 [30] | 514/529 (monomer), 585/590 (aggregate) [32] |

| Detection Mode | Non-quenching or quenching modes [30] | Primarily quenching mode [30] | Ratiometric (monomer/aggregate) [32] |

| Mitochondrial Binding | Low [33] | Moderate [33] | High (J-aggregates) [32] |

| Toxicity/Inhibition | Lowest toxicity and electron transport chain inhibition [33] [30] | Moderate suppression of mitochondrial respiration [33] | Concentration-dependent aggregation sensitivity [30] |

| Optimal Applications | Quantitative analysis of pre-existing ΔΨm; slow-resolving acute studies [30] | Fast-resolving acute studies in quenching mode [30] | "Yes/No" discrimination of polarization state (e.g., apoptosis studies) [30] |

| Typical Working Concentration | 1-30 nM (non-quenching); >50-100 nM (quenching) [30] | ~1-10 μM (quenching mode) [30] | Manufacturer-dependent (follow specific kit protocols) [32] |

Quantitative Binding and Inhibition Data

Table 2: Experimentally determined binding and inhibitory properties

| Parameter | TMRM | Rhodamine 123 | JC-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Affinity | Lowest binding of rhodamine dyes [33] | Intermediate binding [33] | Not quantitatively assessed in available literature |

| Respiratory Control Suppression | Minimal at low concentrations [33] | Moderate suppression [33] | Not quantitatively assessed in available literature |

| Temperature-Dependent Binding | Yes, but to a lesser extent than TMRE or Rhodamine 123 [33] | Significant temperature dependence [33] | Information not available in search results |

Experimental Protocols: Standardized Methodologies

TMRM Staining Protocol for Adherent Cells

The following protocol has been standardized across multiple laboratories in the CeBioND consortium for assessing mitochondrial function in cellular models of neurodegenerative diseases [34]:

Preparation of TMRM working solution:

- Dissolve 1 mg TMRM in 525 μL DMSO to obtain 5 mM stock solution [31].

- Dilute the stock solution in serum-free cell culture medium or PBS to obtain 1-20 μM working solution [31].

- Note: Use the lowest possible concentration that provides sufficient signal-to-noise ratio (typically 1-30 nM for non-quenching mode) [30].

Cell staining procedure:

- Culture adherent cells on sterile coverslips.

- Remove the coverslip from the medium and aspirate excess medium.

- Add 100 μL of working solution, gently shaking to completely cover the cells.

- Incubate at room temperature for 30-60 minutes protected from light [31].

- Wash twice with culture medium, 5 minutes each time [31].

- For non-quenching mode measurements, maintain TMRM in the bath during imaging if test treatment precedes dye loading [30].

Imaging and analysis:

JC-1 Staining Protocol for Apoptosis Detection

Preparation of JC-1 working solution:

Cell staining procedure:

- For adherent cells: Detach cells (collecting cells that detach due to apoptosis from the culture supernatant) and follow protocol for suspended cells if using flow cytometry [32].

- Incubate cells with JC-1 working solution according to manufacturer-recommended concentration and duration.

- Note: JC-1 requires longer load times than commonly reported to ensure proper formation of J-aggregates [30].

Detection and analysis:

- Analyze by flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy.

- In normal cells with high ΔΨm, JC-1 forms aggregates emitting red fluorescence (590 nm).

- In apoptotic cells with low ΔΨm, JC-1 remains in monomeric form emitting green fluorescence (529 nm) [32].

- Calculate the red/green fluorescence ratio to determine ΔΨm changes.

Diagram 1: JC-1 experimental workflow and interpretation guide

Troubleshooting FAQs: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

General Technical Issues with Mitochondrial Dyes

Q: My fluorescent signal is weak, even with healthy cells. What could be the cause?

A: Weak signal can result from several factors:

- Insufficient dye concentration: Optimize dye concentration for your specific cell type and equipment. For TMRM, try increasing within the 1-30 nM range (non-quenching) or 50-100 nM (quenching) [30].

- Inadequate loading time: Ensure proper dye equilibration; for TMRM, typical loading is 30-60 minutes [31].

- Dye precipitation: Filter dye solutions or sonicate if particulates are visible, especially critical for JC-1 [32].

- Photobleaching: Reduce exposure time or use lower light intensity during imaging.

- Loss of mitochondrial potential: Validate with positive controls (e.g., FCCP) [34].

Q: I observe uneven staining patterns in my cell population. Is this normal?

A: Heterogeneous staining can reflect biological reality or technical issues:

- Biological variation: Mitochondrial membrane potential naturally varies among cells based on metabolic state, cell cycle stage, and health status.

- Technical artifacts: Ensure uniform dye distribution during incubation by gentle shaking.

- Cell density effects: Avoid over-confluent cultures which can create microenvironments with varying nutrient/oxygen availability [32].

- Validation: Compare with additional mitochondrial markers (e.g., Mitotracker Green FM for mass) to distinguish potential-dependent from -independent effects [35].

Dye-Specific Technical Challenges

Q: My JC-1 shows red particulate crystals in the working solution. How can I resolve this?

A: This common issue with JC-1 arises from improper preparation or solubility limitations:

- Correct preparation order: Prepare JC-1 working solution strictly following manufacturer's instructions, typically diluting JC-1 (500×) with distilled water first, then adding JC-1 Assay Buffer [32].

- Enhanced dissolution: Promote dissolution by placing in a 37°C water bath or using brief sonication [32].

- Filtration: Filter the working solution through a 0.2 μm filter if precipitates persist.

- Fresh preparation: Always prepare JC-1 working solution fresh just before use.

Q: Can I use TMRM or JC-1 in tissue samples?

A: Tissue applications require specific adaptations:

- Single-cell suspensions: For flow cytometry, prepare tissues into single-cell suspensions first, then follow protocols for suspended cells. Optimize the dissociation process to minimize artificial depolarization [32].

- Mitochondrial isolation: Alternatively, extract mitochondria using commercial mitochondrial extraction kits, then incubate with JC-1, detecting results with a fluorescence plate reader [32].

- Limitations for intact tissues: Ratio fluorescence approaches using the mitochondrial matrix-induced wavelength shift may not work effectively in intact tissues like the perfused heart, as the spectral shift also occurs in the cytosol [33].

Q: Can I fix cells after staining with these dyes for later analysis?

A: Fixation compatibility varies by dye:

- TMRM and Rhodamine 123: Not recommended, as these dyes are readily washed out once mitochondrial membrane potential is lost following fixation [35].

- JC-1: Not compatible with fixation, as JC-1 requires live cells. Fixation causes cell death and fluorescence quenching [32].

- Alternative solutions: For fixed cell applications, consider MitoTracker probes (e.g., MitoTracker Red CMXRos, MitoTracker Deep Red FM) which are fixable due to their thiol-reactive chloromethyl moieties that covalently bind to mitochondrial proteins [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents for mitochondrial membrane potential assays

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| ΔΨm Dyes | TMRM, TMRE, Rhodamine 123, JC-1, DASPEI [30] [36] | Direct monitoring of mitochondrial membrane potential |

| Validation Compounds | FCCP, CCCP, DNP (uncouplers) [30] [36]; Oligomycin (ATP synthase inhibitor) [30] | Instrument validation and control experiments |

| Mitochondrial Mass Markers | MitoTracker Green FM [35], CellLight Mitochondria-GFP/RFP [35] | Discrimination of potential-dependent vs. potential-independent effects |

| Viability Indicators | Propidium iodide, Annexin V, Caspase assays [35] | Correlation of ΔΨm with cell death pathways |

| Sample Preparation | Mitochondria Extraction Kits [32], Density gradient media (sucrose, Percoll, Nycodenz, Optiprep) [37] | Isolation of mitochondria from cells and tissues |

Advanced Considerations: Integrating ΔΨm Measurements with Other Parameters

Diagram 2: Relationship between mitochondrial membrane potential and bioenergetic parameters