TMRE Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the application of Tetramethylrhodamine Ethyl Ester (TMRE) for analyzing mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm).

TMRE Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the application of Tetramethylrhodamine Ethyl Ester (TMRE) for analyzing mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm). It covers the foundational principles of ΔΨm as a key indicator of cellular health and mitochondrial function, detailed protocols for assay setup in various experimental models (including 2D cultures, 3D spheroids, and primary cells), and advanced troubleshooting strategies to ensure data validity. Furthermore, it explores validation techniques, compares TMRE with alternative probes, and discusses its critical role in pre-clinical drug evaluation, particularly in mechanisms involving energy disruption and apoptosis.

Understanding Mitochondrial Membrane Potential: The Foundation of Cellular Energetics and Why It Matters

The Bioenergetic Role of ΔΨm in Oxidative Phosphorylation and ATP Production

Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) is a fundamental component of cellular bioenergetics, representing the electrical potential difference across the inner mitochondrial membrane. This potential results from the electrochemical gradient generated by proton pumps during electron transport chain (ETC) activity and serves as a key intermediate form of energy storage [1]. The primary function of ΔΨm is to drive ATP synthesis through oxidative phosphorylation, making it essential for meeting cellular energy demands, particularly under aerobic conditions [2]. In the broader context of mitochondrial membrane potential analysis with TMRE research, understanding the precise bioenergetic role of ΔΨm provides critical insights for drug development targeting metabolic diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, and cancer [3].

Theoretical Foundation of ΔΨm in Bioenergetics

Generation and Maintenance of ΔΨm

The mitochondrial membrane potential is generated through redox transformations associated with the Krebs cycle and electron transport chain activity. As electrons pass through complexes I, III, and IV of the ETC, protons are pumped from the mitochondrial matrix to the intermembrane space, creating both a chemical (ΔpH) and electrical (ΔΨm) gradient [1]. Together, these components form the proton motive force (Δp), with ΔΨm constituting approximately 80% of this potential energy [4]. The direction of the membrane potential is negative inside, creating a driving force preferred for inward transport of cations and outward transport of anions [1].

ΔΨm as the Driving Force for ATP Production

The central bioenergetic role of ΔΨm lies in its ability to power ATP synthesis through chemiosmotic coupling. The F₁F₀ ATP synthase (Complex V) harnesses the energy stored in ΔΨm by allowing protons to flow back into the mitochondrial matrix through its membrane-embedded F₀ subunit, driving the phosphorylation of ADP to ATP in the F₁ subunit [1] [2]. This coupling mechanism ensures efficient energy transfer from nutrient oxidation to ATP synthesis, with the magnitude of ΔΨm directly influencing the rate and efficiency of ATP production [4].

Table 1: Key Components Involved in ΔΨm Generation and Utilization

| Component | Function in ΔΨm Dynamics | Impact on ATP Production |

|---|---|---|

| Complex I, III, IV | Generate ΔΨm by pumping protons from matrix to intermembrane space | Establish proton motive force essential for ATP synthase function |

| ATP Synthase | Consumes ΔΨm to phosphorylate ADP to ATP | Directly produces ATP; rate-limited by ΔΨm consumption capacity |

| Adenine Nucleotide Translocase (ANT) | Exchanges ATP⁴⁻ for ADP³⁻ consuming one net charge equivalent to 1 H⁺ | Links mitochondrial ATP production to cellular energy demands |

| Uncoupling Proteins (UCPs) | Induce proton leak, dissipating ΔΨm as heat | Decrease ATP synthesis efficiency; regulate ROS production |

Non-Energy Related Functions of ΔΨm

Beyond ATP production, ΔΨm serves as a critical driving force for multiple essential mitochondrial processes. It enables the transport of ions (such as Ca²⁺ and Fe²⁺) and proteins necessary for healthy mitochondrial functioning [1]. Additionally, ΔΨm plays a key role in mitochondrial quality control through selective elimination of dysfunctional mitochondria via mitophagy [1]. The potential also facilitates the import of nucleic acids, including tRNAs, which are essential for mitochondrial gene expression and function [1].

Experimental Protocols for ΔΨm Analysis Using TMRE

TMRE-Based ΔΨm Measurement by Microplate Spectrophotometry

This protocol enables quantitative assessment of ΔΨm in live cells using tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE), a cell-permeant, cationic dye that accumulates in active mitochondria in a potential-dependent manner [3].

Materials and Reagents

- TMRE-Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay Kit (e.g., ab113852) [3]

- Sterile 96-well black microplate (e.g., Corning Costar) [5]

- PBS with 0.02% w/v BSA

- Carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP)

- Plate reader capable of fluorescence measurements (Ex/Em: 549/575 nm)

Procedure

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells at 30,000 cells/well onto a sterile 96-well black microplate 48 hours prior to experimentation [5].

- Treatment Application: After 24 hours, refresh media and apply experimental treatments. Include a control group treated with 1-5 μM FCCP for 10 minutes at 37°C to dissipate ΔΨm [5] [3].

- Dye Preparation: Reconstitute TMRE in sterile DMSO to yield a 100 μM stock solution, then dilute in PBS (0.02% w/v BSA) to a final working concentration of 100-500 nM [5] [3].

- Staining: Wash cells with PBS (0.02% w/v BSA), add TMRE working solution, and incubate for 15-30 minutes at 37°C with 5% CO₂ [5] [3].

- Washing and Measurement: Wash cells 3× with PBS (0.02% w/v BSA) and immediately record fluorescence at Ex/Em 548/574 nm using a plate reader [5].

- Data Normalization: Normalize fluorescence values against total cellular protein content using a BCA protein assay on the same plate [5].

TMRE-Based ΔΨm Measurement by Fluorescent Microscopy

This protocol enables qualitative and semi-quantitative assessment of ΔΨm with subcellular resolution, allowing visualization of mitochondrial distribution and heterogeneity.

Materials and Reagents

- TMRE dye (100-500 nM working concentration)

- Glass-bottom culture dishes or sterile coverslips

- HEPES-buffered salt solution (HBPS) with 0.02% BSA

- Fluorescence microscope with appropriate filter sets (Ex/Em: 549/575 nm)

Procedure

- Cell Preparation: Seed cells at 10,000 cells/well on glass-bottom dishes or coverslips and allow to adhere for 24-48 hours [5].

- Staining: Incubate cells with 100 nM TMRE in HBPS (0.02% BSA) for 20-30 minutes at 37°C [5] [3].

- Washing: Wash cells briefly with pre-warmed PBS or HBPS to remove excess dye [3].

- Imaging: Immediately image using a fluorescence microscope with 20× or higher magnification and appropriate filter sets [5].

- Image Analysis: Quantify fluorescence intensity using image analysis software (e.g., Zen2 Lite, ImageJ) [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for ΔΨm Analysis in TMRE Research

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TMRE (Tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester) | Cationic dye that accumulates in active mitochondria proportional to ΔΨm | Use 100-500 nM working concentration; compatible with live cells only; not fixable [3] |

| FCCP (Carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone) | Protonophore uncoupler that dissipates ΔΨm; serves as negative control | Use 1-5 μM for 10 min pretreatment; validates ΔΨm-dependent staining [5] [3] |

| TMRE-Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay Kit (ab113852) | Complete kit with optimized TMRE and FCCP concentrations | Includes protocol and controls; validated for flow cytometry, microplate reading, and microscopy [3] |

| Oligomycin | ATP synthase inhibitor that increases ΔΨm by preventing consumption | Use to assess ΔΨm dependence on ATP synthase activity; typically 1-5 μg/mL [4] |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Prevents non-specific binding of TMRE; improves washing efficiency | Use at 0.02% in PBS or HBPS washing buffers [5] |

Data Interpretation and Technical Considerations

Quantitative Analysis of ΔΨm Measurements

When interpreting TMRE fluorescence data, researchers must consider the complex relationship between ΔΨm and oxidative phosphorylation parameters. As illustrated in Table 3, ΔΨm values must be interpreted in the context of overall mitochondrial function rather than as isolated measurements [4].

Table 3: Interpreting ΔΨm Changes in the Context of OXPHOS Parameters

| ΔΨm Measurement | O₂ Consumption | ATP Production | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increased ΔΨm | Decreased | Decreased | Restricted proton flow through ATP synthase (e.g., oligomycin treatment) [4] |

| Increased ΔΨm | Increased | Variable | Enhanced ETC activity exceeding ATP synthase capacity (e.g., beta-cells with high glucose) [4] |

| Decreased ΔΨm | Increased | Increased | Elevated ATP demand driving coupled OXPHOS [4] |

| Decreased ΔΨm | Decreased | Decreased | ETC impairment or uncoupling (e.g., FCCP treatment) [1] [4] |

Common Artifacts and Troubleshooting

Several technical considerations are essential for accurate ΔΨm assessment using TMRE:

Dye Concentration Optimization: Excessive TMRE concentrations can induce artifactual fluorescence due to dye aggregation and potential mitochondrial toxicity. Perform concentration curves for each cell type [3].

Timing Considerations: TMRE fluorescence should be measured immediately after staining, as prolonged incubation or delayed measurement can lead to signal loss due to dye leakage or photobleaching [5].

Validation with Controls: Always include FCCP-treated controls to confirm ΔΨm-dependent staining. A minimum 50% reduction in fluorescence with FCCP treatment validates the specificity of the measurement [3].

Instrument Calibration: Regularly calibrate fluorescence detectors using reference standards to ensure inter-experiment comparability, particularly for longitudinal studies.

Advanced Applications in Drug Development Research

The analysis of ΔΨm using TMRE provides critical insights for pharmaceutical research, particularly in screening compounds that modulate mitochondrial function. In neurodegenerative disease research, TMRE-based assays can identify compounds that protect against ΔΨm collapse induced by disease-related toxins [3]. In cancer drug development, researchers can screen for compounds that selectively induce ΔΨm dissipation in cancer cells with altered metabolic profiles [3]. For metabolic disorders, ΔΨm analysis enables assessment of compounds that enhance coupling efficiency and reduce proton leak, potentially improving metabolic efficiency [4] [6].

When implementing these protocols for drug screening, include appropriate controls and validation experiments to distinguish specific mitochondrial effects from non-specific cytotoxicity. Combine TMRE measurements with assessments of oxygen consumption rates and ATP production to obtain a comprehensive view of compound effects on mitochondrial function [4].

ΔΨm as a Central Integrator of Cell Health, Stress Signaling, and Apoptosis

The mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), a electrical potential difference across the inner mitochondrial membrane, serves as a fundamental indicator of cellular bioenergetics and health. Maintained at approximately -180 mV in healthy cells, this potential is generated by the electron transport chain (ETC) which actively pumps protons from the matrix into the intermembrane space, creating an electrochemical gradient [7]. This gradient represents a key component of the proton motive force that drives ATP synthesis through the rotation of ATP synthase, coupling substrate oxidation to cellular energy production [4]. Beyond its fundamental role in bioenergetics, ΔΨm has emerged as a central integrator of cellular stress signaling and a decisive factor in the intrinsic apoptosis pathway, making it a critical parameter for assessing mitochondrial function in health and disease [8] [9].

The significance of ΔΨm extends far beyond energy production, as it regulates multiple essential mitochondrial processes including protein import, ion homeostasis, and metabolic signaling [10]. Recent research has revealed that chronic alterations in ΔΨm, particularly hyperpolarization, can induce pervasive molecular and genomic changes, including nuclear DNA hypermethylation and extensive transcriptional reprogramming [10]. This positions ΔΨm as a key signaling intermediary that communicates mitochondrial status to the rest of the cell, influencing fate decisions ranging from proliferation to programmed cell death. Consequently, accurate measurement and interpretation of ΔΨm provides invaluable insights into cellular health, pharmacological responses, and disease mechanisms, making it an essential tool for researchers across biomedical disciplines.

Key Applications and Functional Significance of ΔΨm Analysis

ΔΨm as a Marker of Mitochondrial Function and Cellular Energetics

ΔΨm serves as a sensitive indicator of mitochondrial coupling efficiency and overall bioenergetic capacity. In coupled mitochondria, the generation of ΔΨm by the ETC is balanced by its consumption through ATP synthase activity to produce ATP [4]. However, this relationship is not always straightforward, as different perturbations to oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) can produce similar changes in ΔΨm, highlighting the need for complementary measurements to fully interpret bioenergetic status. For instance, inhibition of ATP synthase with oligomycin typically increases ΔΨm while decreasing oxygen consumption, whereas increased ATP demand can stimulate both respiration and ΔΨm consumption, potentially leading to a decrease in ΔΨm despite enhanced mitochondrial function [4]. This complexity underscores that ΔΨm must be interpreted within the specific cellular context, considering that both hyperpolarization and depolarization can indicate pathological or adaptive states depending on the underlying mechanism.

ΔΨm in Stress Signaling and Cellular Adaptation

Recent evidence has established that chronic alterations in ΔΨm trigger extensive cellular reprogramming beyond immediate bioenergetic effects. Studies using genetic models of mitochondrial hyperpolarization (IF1-KO cells) demonstrate that sustained elevation in ΔΨm induces nuclear DNA hypermethylation and remodeling of phospholipid composition, subsequently modulating the transcription of genes involved in mitochondrial function, carbohydrate metabolism, and lipid processing [10]. These transcriptional changes include downregulation of ETC components and mitoribosome genes, suggesting a compensatory adaptation to chronic hyperpolarization [10]. Importantly, these effects can be replicated in wild-type cells exposed to environmental chemicals that cause hyperpolarization, indicating a conserved mechanism through which mitochondrial stress signals can epigenetically reshape cellular phenotype, with potential implications for chemical toxicity and disease pathogenesis.

ΔΨm in Apoptosis Regulation

The role of ΔΨm in apoptosis represents one of its most clinically significant functions. During the intrinsic apoptosis pathway, mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) leads to the release of cytochrome c and other pro-apoptotic factors from the intermembrane space into the cytosol [8]. Cytochrome c release impairs electron shuttle between Complex III and IV, resulting in rapid dissipation of ΔΨm, which often serves as a surrogate marker for this committed step in apoptosis [7]. This permeability transition is regulated by Bcl-2 family proteins, which determine the threshold for apoptosis induction in response to diverse cellular stresses [8]. Notably, research has demonstrated that cytochrome c release and ΔΨm loss can be functionally dissociated in some apoptotic contexts, with cytochrome c release occurring independently of complete ΔΨm collapse in granzyme B-induced apoptosis [9]. This nuanced relationship highlights the importance of multi-parameter assessment when studying apoptotic mechanisms.

Table 1: Key Functional Roles of ΔΨm in Cellular Physiology

| Functional Domain | Specific Role | Physiological Significance | Pathological Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioenergetics | Drives ATP synthesis through proton motive force | Maintains cellular energy homeostasis | Neurodegeneration, metabolic syndromes |

| Calcium Signaling | Facilitates mitochondrial Ca²⁺ uptake through the electrophoretic uniporter | Regulates TCA cycle dehydrogenases, shapes cytosolic Ca²⁺ transients | Calcium overload conditions, excitotoxicity |

| Reactive Oxygen Species | Threshold-dependent ROS production at high ΔΨm | Redox signaling, oxidative damage | Aging, inflammatory diseases, cancer |

| Apoptosis Regulation | Loss associated with cytochrome c release and MOMP | Determines cellular fate in response to stress | Cancer chemoresistance, degenerative disorders |

| Epigenetic Modulation | Hyperpolarization-linked nuclear DNA methylation changes | Gene expression regulation, cellular adaptation | Environmental toxicant effects, cancer epigenetics |

TMRE-Based Analysis of ΔΨm: Detailed Experimental Protocol

TMRE Staining Principle and Advantages

Tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) is a cell-permeant, cationic fluorescent dye that accumulates in active mitochondria in a ΔΨm-dependent manner [7]. In healthy cells with intact ΔΨm, TMRE enters the mitochondrial matrix and emits strong red fluorescence due to the negative charge of the mitochondrial interior. As ΔΨm dissipates, TMRE accumulation decreases, resulting in diminished fluorescence signal [7]. This property makes TMRE an excellent probe for monitoring changes in mitochondrial polarization status across various experimental conditions. Compared to alternative dyes, TMRE offers several advantages, including relatively low toxicity to live cells, reversible binding, and compatibility with various detection platforms including fluorescence microscopy, flow cytometry, and plate-based assays. The quantitative nature of TMRE fluorescence intensity allows for robust comparison of ΔΨm between experimental groups when proper normalization procedures are followed.

Step-by-Step TMRE Staining Protocol for Flow Cytometry

The following protocol provides a standardized approach for ΔΨm measurement using TMRE staining and flow cytometric analysis, adapted from established methodologies [7] [11]:

Preparation of Staining Solution: Create a 50 μM intermediate dilution of TMRE in complete cell culture medium from a 10 mM DMSO stock solution. Further dilute to the working concentration of 250 nM in pre-warmed culture medium. Protect from light during preparation and use.

Cell Staining Procedure:

- Culture cells in appropriate growth conditions until they reach 70-80% confluence.

- For suspension cells: Collect cells by gentle centrifugation (300 × g for 5 minutes) and resuspend in TMRE staining solution at a density of 0.5-1 × 10⁶ cells/mL.

- For adherent cells: Aspirate culture medium and add TMRE staining solution directly to the culture vessel.

- Incubate cells for 30 minutes at 37°C in a CO₂ incubator protected from light.

Sample Processing:

- For suspension cells: Centrifuge stained cells (300 × g for 5 minutes), carefully aspirate supernatant, and resuspend in fresh pre-warmed culture medium or PBS.

- For adherent cells: Gently wash twice with pre-warmed PBS or culture medium after incubation, then trypsinize and resuspend in fresh medium.

- Keep samples on ice or at room temperature protected from light until analysis (typically within 1 hour).

Flow Cytometry Acquisition:

- Use a flow cytometer equipped with a 488 nm or 561 nm laser for excitation.

- Detect TMRE fluorescence using a 575/26 nm or similar bandpass filter (PE channel).

- Collect a minimum of 10,000 events per sample for statistical robustness.

- Include appropriate controls: unstained cells, FCCP-treated depolarized controls (50-100 μM for 15-30 minutes prior to staining), and potential inhibitor controls as needed.

Data Analysis:

- Gate on viable cells based on forward and side scatter properties to exclude debris and dead cells.

- Compare mean or median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of TMRE staining between experimental conditions.

- Normalize data to negative controls (FCCP-treated cells) and express as percentage of control or fold-change relative to baseline.

Table 2: Essential Controls for TMRE-Based ΔΨm Assays

| Control Type | Purpose | Preparation Method | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unstained Cells | Autofluorescence baseline | Cells without TMRE staining | Defines negative fluorescence threshold |

| FCCP-treated (50-100 μM) | Maximum depolarization control | Pre-incubate 15-30 min before TMRE staining | 70-90% reduction in TMRE signal |

| Oligomycin (1-10 μM) | Hyperpolarization control | Pre-incubate 15-30 min before TMRE staining | 20-40% increase in TMRE signal |

| Valinomycin (1-10 μM) | K⁺-specific depolarization | Pre-incubate 15-30 min before TMRE staining | Concentration-dependent depolarization |

| DMSO Vehicle | Solvent control | Same DMSO concentration as experimental treatments | Validates specific drug effects vs. solvent artifacts |

Critical Optimization Parameters and Troubleshooting

Successful implementation of TMRE staining requires careful optimization of several key parameters:

Dye Concentration Titration: While 250 nM works for many cell types, optimal concentration should be determined empirically for each cell type by testing a range from 50-500 nM. Select the lowest concentration that provides robust signal-to-noise ratio.

Loading Time and Temperature: Standard incubation is 30 minutes at 37°C, but certain cell types may require adjustment (15-60 minutes). Lower temperatures or shorter incubations may be necessary for highly active cells with significant dye efflux.

Compatibility with Multiplexing: TMRE can be combined with other probes in multiparametric assays. When measuring apoptosis concurrently with ΔΨm, annexin V-FITC (for phosphatidylserine exposure) can be used with TMRE, with careful compensation between FITC and PE channels [12].

Normalization Strategies: For more quantitative comparisons, normalize TMRE fluorescence to mitochondrial mass using concurrent staining with mitochondrial dyes such as MitoTracker Green (incubated at 50-200 nM for 30 minutes), which accumulates independently of ΔΨm [10].

Instrument Calibration: Regular calibration with fluorescent beads ensures consistent performance across experiments. Verify laser alignment and detector sensitivity before each acquisition session.

Complementary Methods for ΔΨm Assessment

JC-1: A Ratiometric Alternative for ΔΨm Measurement

The JC-1 dye represents a powerful alternative to TMRE, particularly when ratiometric measurements are desired. JC-1 exhibits potential-dependent accumulation in mitochondria, forming red fluorescent J-aggregates (~590 nm emission) at hyperpolarized potentials, while remaining as green fluorescent monomers (~529 nm emission) at depolarized potentials [13]. This emission shift enables quantitative assessment of ΔΨm through the red/green fluorescence ratio, which minimizes potential artifacts related to mitochondrial density, dye loading efficiency, or cell size [13]. The MitoProbe JC-1 Assay Kit provides an optimized system for flow cytometric applications, with established protocols for detecting apoptosis-induced mitochondrial depolarization [13]. For imaging applications, JC-1 enables visualization of heterogeneous mitochondrial populations within single cells, with polarized mitochondria appearing orange-red and depolarized mitochondria appearing green [13].

Multiparametric Approaches for Comprehensive Cell Health Assessment

Integrating ΔΨm measurement with complementary parameters provides a more comprehensive assessment of cellular status. A robust flow cytometry-based methodology has been developed that simultaneously evaluates proliferation (BrdU or CellTrace Violet), cell cycle distribution (propidium iodide), apoptosis (annexin V), and mitochondrial depolarization (JC-1) from a single sample [12]. This multiparametric approach enables researchers to distinguish whether changes in cell numbers result from altered proliferation or increased cell death, and whether mitochondrial dysfunction underlies these phenotypic changes [12]. For specialized applications, additional parameters such as caspase activation, ROS production (using DCFDA or DHR), or DNA damage (γH2AX) can be incorporated to address specific research questions [12].

Data Interpretation and Methodological Considerations

Interpreting ΔΨm in the Context of OXPHOS Function

Proper interpretation of ΔΨm measurements requires understanding its relationship to overall mitochondrial physiology. As recently emphasized in methodological commentaries, ΔΨm has limited sensitivity and specificity for reporting changes in OXPHOS activity in coupled mitochondria [4]. Different perturbations to the OXPHOS system can produce similar ΔΨm signatures—for example, both inhibition of ATP synthase and stimulation of electron transport can cause hyperpolarization through distinct mechanisms [4]. Consequently, researchers should complement ΔΨm measurements with assessments of oxygen consumption rates where possible, and carefully design experimental controls to distinguish between specific bioenergetic perturbations. The interpretation framework should consider whether observed ΔΨm changes reflect alterations in ΔΨm generation (ETC activity), consumption (ATP synthesis demand), or coupling efficiency (proton leak).

Common Pitfalls and Technical Considerations

Several methodological considerations are essential for robust ΔΨm measurement:

Dye Toxicity and Artifacts: High concentrations of potentiometric dyes can themselves induce mitochondrial toxicity or uncoupling. Always use the minimum effective concentration and include vehicle controls.

Instrument Sensitivity: Ensure flow cytometer detectors can adequately resolve the dynamic range of TMRE fluorescence, which may require PMT voltage optimization for each cell type.

Cell Health Status: Stress during cell processing can significantly impact ΔΨm. Maintain consistent handling procedures and minimize processing time.

Appropriate Gating: Exclude debris, dead cells, and aggregates through careful forward/side scatter gating and potentially viability dye exclusion.

Contextual Interpretation: Consider cell-type specific differences in baseline ΔΨm and response to stimuli when comparing across experimental systems.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ΔΨm Analysis

| Reagent/Assay | Primary Application | Key Features | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMRE | ΔΨm measurement by flow cytometry, microscopy | Low toxicity, reversible binding, compatible with multiplexing | Thermo Fisher, Sigma-Aldrich, Cayman Chemical |

| JC-1 (MitoProbe Kit) | Ratiometric ΔΨm assessment | Potential-dependent emission shift (green/red), quantitative ratio measurements | Thermo Fisher (M34152), Abcam, Cayman Chemical |

| TMRM | ΔΨm measurement with lower toxicity | Similar to TMRE but with potentially reduced toxicity in sensitive cells | Thermo Fisher, Sigma-Aldrich, AAT Bioquest |

| m-MPI Assay | High-throughput screening | Homogenous format, red/green ratio compatible with 1536-well plates | Codex BioSolutions [14] |

| FCCP | Depolarization control | Protonophore, uncouples OXPHOS, validates ΔΨm-dependent staining | Sigma-Aldrich, Tocris, Cayman Chemical |

| Oligomycin | Hyperpolarization control | ATP synthase inhibitor, increases ΔΨm by reducing consumption | Sigma-Aldrich, Tocris, Cayman Chemical |

| MitoTracker Green | Mitochondrial mass normalization | ΔΨm-independent staining, normalizes for mitochondrial content | Thermo Fisher, Abcam |

| Annexin V Conjugates | Apoptosis detection (multiplexing) | Detects phosphatidylserine exposure, combined with ΔΨm for apoptosis staging | Thermo Fisher, BioLegend, Abcam |

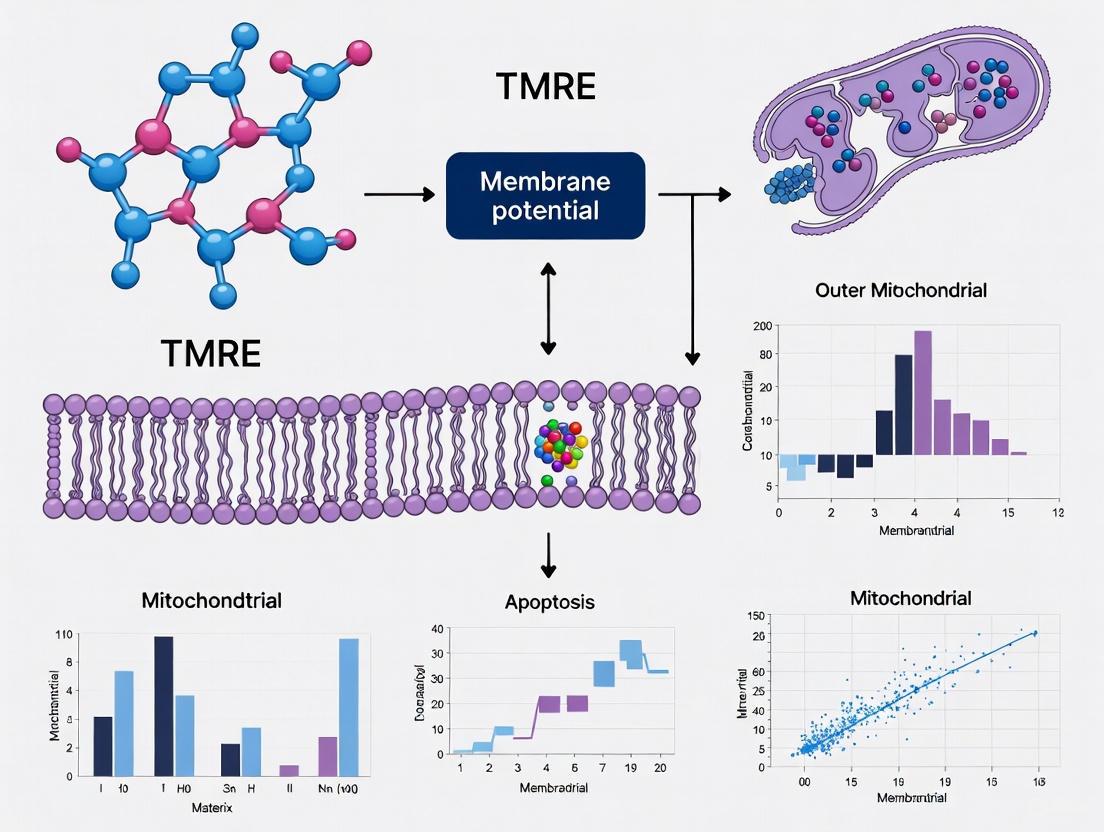

Integrated ΔΨm Signaling Network - This diagram illustrates how ΔΨm functions as a central integrator in cellular stress response pathways, influencing both adaptive signaling and commitment to apoptotic cell death.

TMRE ΔΨm Analysis Workflow - This workflow outlines the key steps in TMRE-based ΔΨm assessment, highlighting the integration of essential experimental controls throughout the procedure.

The mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) is a fundamental component of cellular bioenergetics, generated by the electron transport chain (ETC) as protons are pumped across the inner mitochondrial membrane. This creates an electrochemical gradient with a typical value of -150 to -180 mV (matrix negative) relative to the cytosol [15] [16]. This potential difference accounts for the majority of the proton motive force (Δp) that drives ATP synthesis through ATP synthase (Complex V) [15]. The maintenance of ΔΨm is critical not only for ATP production but also for mitochondrial calcium homeostasis, reactive oxygen species regulation, and overall cellular health assessment in biomedical research [15] [17].

Tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) belongs to a class of lipophilic cationic dyes that serve as sensitive reporters of ΔΨm in live cells. As a cell-permeant, positively-charged fluorophore, TMRE distributes across membranes in response to electrical gradients, following the principles of the Nernst equation [15] [16]. In the context of mitochondrial function assessment, particularly in cancer research and drug development, TMRE provides researchers with a valuable tool for monitoring metabolic alterations and cellular stress responses [17] [3]. Its application spans multiple detection platforms including fluorescence microscopy, flow cytometry, and microplate-based assays, making it versatile for various experimental setups in basic biological research and pharmaceutical screening [3].

Electrochemical Principles of TMRE Accumulation

The Nernstian Distribution Principle

The accumulation of TMRE in mitochondria follows the Nernst equation, which describes the equilibrium distribution of a permeant ion across a membrane under an electrical potential gradient. For a monovalent cation like TMRE at 37°C, the Nernst equation is expressed as:

ΔΨ = -61.5 log([TMRE]m/[TMRE]c)

Where ΔΨ represents the membrane potential in millivolts, [TMRE]m is the TMRE concentration in the mitochondrial matrix, and [TMRE]c is the concentration in the cytosol [15] [16]. This relationship demonstrates that TMRE accumulates exponentially with increasing membrane potential. A typical resting mitochondrial potential of -180 mV would theoretically result in approximately a 1000-fold higher concentration of TMRE in the matrix compared to the cytosol, though actual accumulation is influenced by additional factors including dye binding to mitochondrial membranes [16] [18].

The driving force for TMRE accumulation is fundamentally electrophoretic - the positively charged dye molecules are attracted to the negatively charged mitochondrial interior [15] [19]. This potential-dependent accumulation makes TMRE fluorescence intensity a sensitive indicator of changes in ΔΨm, with depolarization (less negative potential) causing dye release and decreased fluorescence, while hyperpolarization (more negative potential) enhances dye uptake and fluorescence signal [15].

TMRE Properties and Spectroscopic Characteristics

TMRE is a red-orange fluorescent dye with excitation/emission maxima of approximately 549/575 nm [3]. Its chemical structure includes a delocalized positive charge that facilitates membrane permeability and a lipophilic moiety that promotes accumulation in lipid environments like mitochondrial membranes [15] [16]. Unlike some other mitochondrial dyes, TMRE exhibits a red shift in both absorption and emission spectra when it accumulates in the hydrophobic mitochondrial environment, providing a potential mechanism for rationetric measurements [20].

A critical operational consideration is the concentration-dependent behavior of TMRE. At low concentrations (typically 1-30 nM), TMRE operates in non-quenching mode, where fluorescence intensity is directly proportional to dye concentration and thus to ΔΨm [15] [18]. At higher concentrations (>50-100 nM), TMRE enters quenching mode due to dye aggregation, where fluorescence is self-quenched at high intramitochondrial concentrations, and depolarization leads to dye release and consequent fluorescence dequenching (increased fluorescence) [15]. For most quantitative applications, the non-quenching mode is preferred as it provides a more straightforward relationship between fluorescence intensity and membrane potential [15] [18].

Table 1: Key Properties of TMRE and Related ΔΨm Probes

| Probe | Spectra (Ex/Em) | Operating Modes | Key Advantages | Potential Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMRE | ~549/575 nm [3] | Non-quenching (1-30 nM) or quenching (>50-100 nM) [15] | Low mitochondrial binding and minimal ETC inhibition; suitable for long-term and acute studies [15] | Requires careful concentration optimization; potential phototoxicity at high laser powers |

| TMRM | Similar to TMRE | Same as TMRE | Similar to TMRE but with slightly less membrane binding [15] [20] | Similar to TMRE |

| Rhodamine 123 | ~507/529 nm | Primarily quenching mode (~1-10 μM) [15] | Slow equilibration makes quenching/unquenching easier to detect [15] | More ETC inhibition than TMRM/TMRE [15] |

| JC-1 | 514/529 nm (monomer); 585/590 nm (J-aggregate) | Dual-emission rationetric | "Yes/No" discrimination of polarization state; internal rationetric control [15] | Very sensitive to concentration; aggregate form sensitive to non-ΔΨm factors [15] |

Practical Application Guides

TMRE Staining Protocol for ΔΨm Assessment

The following protocol summarizes established methodologies for TMRE staining to assess mitochondrial membrane potential in live cells using various detection platforms [21] [3] [18]:

Cell Preparation: Seed cells at appropriate density (e.g., 5,000-50,000 cells per well in 96-well plates) and culture for 24-48 hours to reach desired confluence [21].

Experimental Treatment: Apply test compounds or interventions according to experimental design. Include appropriate controls:

- Negative Control: Cells treated with mitochondrial uncouplers such as FCCP (carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone) at 10-50 μM for 20-30 minutes to completely depolarize mitochondria and establish baseline fluorescence [21] [3].

- Vehicle Control: Cells treated with dye solvent (typically DMSO) at equivalent concentration to account for solvent effects [21].

TMRE Loading:

- Prepare TMRE working solution in pre-warmed culture medium or PBS at concentrations typically ranging from 50-500 nM, optimized for specific cell type and detection method [21] [3] [18].

- Incubate cells with TMRE solution for 15-45 minutes at 37°C in the dark [3].

- For non-quenching mode, use lower TMRE concentrations (1-30 nM); for quenching mode, use higher concentrations (>50-100 nM) [15].

Washing and Preparation for Imaging:

Detection and Analysis:

- Microplate Reader: Read fluorescence at excitation/emission of 544/584 nm [21].

- Flow Cytometry: Use 488 nm laser for excitation and detect emission at ~575 nm [3].

- Fluorescence Microscopy: Use appropriate filter sets for tetramethylrhodamine; widefield, confocal, or multiphoton microscopy can be employed [17].

Table 2: TMRE Staining Conditions Across Different Experimental Systems

| Cell Type | TMRE Concentration | Incubation Time | Detection Method | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jurkat cells [3] | 100-500 nM | 30-45 minutes | Flow cytometry, microplate reader | Apoptosis studies, drug screening |

| HeLa cells [3] | 200 nM | 20 minutes | Fluorescence microscopy | Cancer cell metabolism |

| Smooth muscle cells [18] | 2.5-25 nM | 10 minutes + equilibration | High-speed 3D imaging | Mitochondrial flicker analysis |

| P19 neurons [3] | 500 nM | 30-45 minutes | Microplate reader | Neurotoxicity assessment |

| MSCs [22] | 50 nM | Not specified | Flow cytometry | Mitochondrial transfer studies |

Critical Controls and Validation Experiments

Proper interpretation of TMRE fluorescence requires implementation of critical controls to ensure that observed fluorescence changes genuinely reflect alterations in ΔΨm rather than confounding factors:

Uncoupler Control: Treatment with protonophores like FCCP (10-50 μM) that collapse the proton gradient and depolarize mitochondria provides a baseline for minimal ΔΨm-dependent staining [21] [3]. A significant decrease in TMRE fluorescence after FCCP treatment validates that dye accumulation is potential-dependent.

Inhibitor Controls: Using compounds that affect ETC function helps contextualize results:

Concentration Optimization: Perform TMRE titration experiments to determine the optimal concentration for specific cell types and experimental conditions, ensuring operation in the desired mode (quenching vs. non-quenching) [15] [18].

Membrane Potential Independence Testing: When investigating potential non-specific dye effects, compare TMRE staining with mitochondrial proteins tagged with fluorescent proteins (e.g., COX8a-GFP, TOM20-GFP) that localize to mitochondria independent of ΔΨm [22].

Cell Health Assessment: Combine TMRE staining with viability markers to exclude fluorescence changes resulting from plasma membrane permeability or cell death [3].

Experimental Workflow for TMRE-Based ΔΨm Assessment

Technical Considerations and Potential Limitations

Common Pitfalls and Troubleshooting

Despite its widespread use, TMRE-based ΔΨm assessment presents several technical challenges that require careful consideration:

Dye Concentration Effects: Inappropriate TMRE concentration is a frequent source of erroneous interpretation. Excessive dye concentrations can cause artifactual fluorescence due to non-specific binding or induce mitochondrial toxicity by inhibiting electron transport chain function [15] [20]. TMRE has been shown to suppress mitochondrial respiratory control, with inhibition being more pronounced than with the closely related TMRM [20]. Always perform initial concentration titration for new cell types or experimental conditions.

Non-Specific Staining: While TMRE is considered relatively specific for mitochondria due to their high membrane potential, recent evidence suggests that cationic dyes can accumulate in other cellular compartments with membrane potential, including endoplasmic reticulum and plasma membrane, particularly when used at higher concentrations [22]. This non-specific accumulation can lead to overestimation of mitochondrial mass or potential.

Photobleaching and Phototoxicity: TMRE is susceptible to photobleaching under prolonged or intense illumination, potentially leading to underestimation of fluorescence intensity [17]. Furthermore, light exposure can generate reactive oxygen species that indirectly affect ΔΨm. Implement appropriate controls for photobleaching and use minimal necessary light exposure during imaging.

Influence of Plasma Membrane Potential: Changes in plasma membrane potential can affect TMRE uptake into the cell, consequently influencing mitochondrial accumulation independent of ΔΨm [18]. For precise ΔΨm measurements, researchers have voltage-clamped the plasma membrane to 0 mV to eliminate this confounding factor [18].

Dye Leakage and Redistribution: TMRE can leak out of cells over time or redistribute during experimental manipulations, particularly after fixation [19]. This necessitates careful timing of measurements after loading and avoidance of fixatives for live-cell imaging.

Limitations in Interpreting TMRE Fluorescence

Several fundamental limitations affect the interpretation of TMRE fluorescence data:

ΔΨm vs. ΔpHm Distinction: TMRE and related cationic dyes measure only the electrical component (ΔΨm) of the total proton motive force (Δp). The pH gradient (ΔpHm) constitutes a significant portion of Δp (typically 30-60 mV out of 180-220 mV total) but is not detected by these dyes [15]. Changes in mitochondrial pH can occur independently of ΔΨm alterations, potentially leading to misinterpretation of mitochondrial energetic status [15].

Non-Protonic Charge Effects: Intracellular ion changes, particularly calcium fluxes, can influence ΔΨm measurements independently of protonic gradients. Studies have demonstrated conditions where mitochondrial hyperpolarization detected by TMRE occurred concurrently with matrix acidification, contrary to expected coupling between electrical and chemical gradients [15]. This highlights that TMRE cannot distinguish between charge contributions from protons versus other ions like Ca²⁺ [15].

Quantitative Challenges: While TMRE distribution follows Nernstian principles, quantitative determination of absolute ΔΨm values is complicated by dye binding to mitochondrial membranes, which varies with temperature and mitochondrial physiological state [18] [20]. Binding effectively increases the apparent accumulation beyond that predicted by the Nernst equation for the free dye concentration [20].

Artifacts in Mitochondrial Transfer Studies: Recent investigations have revealed significant limitations using TMRE and similar dyes as surrogates for actual mitochondrial transfer between cells. Comparative studies demonstrate that TMRE signal transfers between cells at much higher efficiency than mitochondrial-targeted fluorescent proteins, suggesting direct dye transfer rather than organelle movement [22]. This calls for caution in interpreting dye redistribution as evidence of mitochondrial trafficking.

TMRE Behavior: Principle and Confounding Factors

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for TMRE-Based ΔΨm Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| TMRE Assay Kits (e.g., ab113852) [3] | Complete kits including TMRE and FCCP control | Provide standardized protocols and optimized reagent concentrations; suitable for multi-platform detection |

| FCCP [21] [3] | Proton ionophore; mitochondrial uncoupler | Used as negative control to collapse ΔΨm; typically used at 10-50 μM for 20-30 minutes |

| Oligomycin [15] | ATP synthase inhibitor | Used to induce hyperpolarization; helps distinguish ΔΨm changes related to ATP synthesis |

| Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) | Alternative mitochondrial uncoupler | Similar function to FCCP; different potency and solubility profile |

| MitoTracker Probes [19] | Fixable mitochondrial dyes | Useful for comparison studies; some variants (e.g., MitoTracker Green FM) show different potential dependence |

| CellLight Mitochondrial Fluorescent Proteins [19] | Genetic labeling of mitochondria | Provide potential-independent mitochondrial localization; useful for normalization and control experiments |

| MitoSOX Red [19] | Mitochondrial superoxide indicator | Can be combined with TMRE for multi-parameter assessment of mitochondrial function |

| Rotenone and Antimycin A | ETC complex inhibitors | Used to investigate specific sites of respiratory chain dysfunction affecting ΔΨm |

Advanced Applications and Future Perspectives

TMRE-based ΔΨm assessment continues to evolve with advancing imaging technologies and experimental approaches. High-speed 3D imaging techniques have enabled the quantification of spontaneous, transient mitochondrial depolarizations ("flickers") with millivolt resolution, revealing heterogeneous mitochondrial behavior within individual cells [18]. These flickers, ranging from <10 mV to >100 mV in amplitude, represent dynamic mitochondrial responses to various physiological stimuli and stressors [18].

The integration of TMRE staining with advanced microscopy modalities including multiphoton microscopy and fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) provides enhanced spatial resolution and quantitative capabilities, particularly valuable for investigating mitochondrial heterogeneity in complex tissues and cancer models [17]. Furthermore, the combination of TMRE with other fluorescent indicators of mitochondrial function (e.g., Ca²⁺ sensors, ROS probes) enables multi-parameter assessment of mitochondrial physiology in live cells [17] [19].

Emerging concerns about potential limitations of TMRE and similar dyes in specific applications, particularly in mitochondrial transfer studies [22], highlight the importance of complementary approaches using genetic fluorescent protein tags for definitive mitochondrial tracking. Future methodological developments will likely focus on improving specificity, reducing phototoxicity, and enabling absolute quantification of ΔΨm rather than relative changes.

When appropriately applied with necessary controls and awareness of its limitations, TMRE remains a powerful tool for investigating mitochondrial function in health and disease, contributing significantly to our understanding of cellular bioenergetics in basic research and drug discovery applications.

Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), the electrical gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane, is a central parameter of mitochondrial function and cellular health [23]. It is generated by the electron transport chain (ETC), which pumps protons from the matrix into the intermembrane space, creating an electrochemical gradient that drives ATP synthesis [24] [25]. This proton motive force is fundamental for energy production, reactive oxygen species (ROS) regulation, calcium buffering, and apoptotic signaling [24] [25]. Consequently, deviations in ΔΨm are critical biomarkers in pathologies ranging from neurodegeneration to cancer. This application note details the central role of ΔΨm analysis, specifically using the fluorescent probe Tetramethylrhodamine Ethyl Ester (TMRE), within research frameworks investigating neurodegenerative diseases, cancer biology, and toxicological screening.

Table 1: Key Functional Roles of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

| Functional Role | Biological Significance | Pathological Consequences of Dysregulation |

|---|---|---|

| ATP Synthesis | Drives proton flux through F1F0 ATP synthase to produce cellular energy [24]. | Energy depletion, impaired cellular function [25]. |

| Calcium Buffering | Facilitates mitochondrial calcium uptake, regulating cytosolic calcium levels and signaling [25]. | Disrupted calcium homeostasis, exacerbation of excitotoxicity [25]. |

| ROS Production | ΔΨm above ~140 mV exponentially increases ROS production, particularly at ETC complexes I and III [24]. | Oxidative stress, damage to cellular macromolecules [23] [24]. |

| Apoptotic Regulation | ΔΨm collapse often precedes cytochrome c release and caspase activation [23]. | Dysregulated cell death; either excessive (neurodegeneration) or impaired (cancer) [23] [24]. |

| Protein Import | Required for the import of nuclear-encoded proteins into the mitochondrial matrix [25]. | Defective mitochondrial biogenesis and function [25]. |

ΔΨm in Biological Contexts

ΔΨm in Neurodegeneration

In neurons, ΔΨm is not uniform; a spatial gradient exists where the potential is highest in the soma and decreases along the axons, making distal synaptic mitochondria inherently more vulnerable to stress [23]. Neurodegeneration often proceeds via a "two-hit" model [23]. The first hit is this pre-existing lower ΔΨm at synapses. A second hit, such as expression of mutant proteins (e.g., amyloid-β in Alzheimer's disease), oxidative stress, or aging, can push these vulnerable mitochondria over the threshold, triggering synaptic degeneration through sub-lethal caspase activation and cytokine production [23]. Furthermore, ΔΨm is essential for mitochondrial dynamics—fusion, fission, and trafficking—processes critical for neuronal health. Sustained depolarization excludes mitochondria from the fusion pool, targeting them for autophagic removal (mitophagy) [25].

ΔΨm in Cancer Biology

Cancer cells frequently exhibit an abnormally high ΔΨm (hyperpolarization) compared to their normal counterparts [24]. This elevated potential is associated with decreased susceptibility to apoptosis and enhanced invasive and metastatic potential [24]. In vivo models show that cancer cells with high ΔΨm lead to a greater metastatic burden than those with low ΔΨm [24]. The hyperpolarized state can also drive excessive ROS production, which can act as a signaling molecule to promote proliferative pathways [24]. Furthermore, ΔΨm is implicated in therapeutic resistance, as a decrease in ΔΨm has been identified as an indicator of radioresistant cancer cells [26]. Recent evidence also positions ΔΨm as a retrograde signal that regulates cell cycle progression, where decreased ΔΨm delays the G1-to-S phase transition [27].

ΔΨm in Toxicity Screening and Drug Development

ΔΨm is a sensitive indicator of drug-induced mitochondrial toxicity. Many pharmacological agents, including certain phenylpropanoids studied in neurodegeneration, exhibit a biphasic, concentration-dependent effect on ΔΨm [23]. At low concentrations, compounds like EGCG or quercetin can protect ΔΨm and restore mitochondrial function. However, at higher concentrations, they may induce ΔΨm dissipation and apoptosis [23]. This underscores the critical importance of dose-response study designs in toxicological screening. Assays measuring ΔΨm are therefore vital for identifying both protective compounds and off-target mitochondrial toxicities in drug development pipelines.

Table 2: Pharmacological Modulators of ΔΨm in Research

| Compound | Target/Activity | Effect on ΔΨm | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| FCCP/CCCP | Protonophore (Uncoupler) | Depolarization (↓ ΔΨm) [28] | Positive control for depolarization; induces mitophagy [29]. |

| Oligomycin | ATP Synthase Inhibitor | Hyperpolarization (↑ ΔΨm) [28] [30] | Inhibits proton flux back into matrix, increasing ΔΨm but reducing ATP production. |

| Antimycin A | Complex III Inhibitor | Depolarization (↓ ΔΨm) [30] | Inhibits ETC, reduces proton pumping. Can increase ROS [24]. |

| BAM15 | Uncoupler | Depolarization (↓ ΔΨm) [27] | Dissipates ΔΨm without depolarizing plasma membrane [27]. |

| PMI | P62-mediated mitophagy inducer | Independent (No change) [29] | Indces mitophagy without collapsing ΔΨm, avoiding toxicity [29]. |

| EGCG/Quercetin | Polyphenols (Biphasic) | Low conc.: Protection; High conc.: Depolarization [23] | Models for concentration-dependent toxicity and therapeutic windows. |

TMRE-Based Analysis of ΔΨm: Protocols and Applications

TMRE Staining Protocol for Live-Cell Imaging

TMRE is a cell-permeant, cationic fluorescent dye that accumulates in active mitochondria in a ΔΨm-dependent manner. The following protocol is adapted for rat cortical neurons [28] but is applicable to various cell lines with minimal modifications.

Key Reagents:

- TMRE Stock Solution: 10 mM in anhydrous DMSO. Store in aliquots at -20°C, protected from light [28].

- Tyrode's Buffer (TB): 145 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM Glucose, 1.5 mM CaCl₂, 1 mM MgCl₂, 10 mM HEPES; adjust pH to 7.4 with NaOH [28].

Staining Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Culture cells on glass-bottom dishes (e.g., MatTek). Wash cells 3 times with pre-warmed TB or culture medium to remove serum [28].

- Dye Loading:

- Post-Incubation: For imaging, after incubation, mount the dish on the microscope stage in fresh TB with 50 nM TMRE to maintain equilibrium distribution [28] [30]. For flow cytometry, resuspend dye-loaded cells in cold DPBS with 1% FBS and analyze immediately [31].

Live-Cell Imaging and Data Analysis

Image Acquisition:

- Use a confocal laser-scanning microscope with a 63x oil immersion objective [28] [30].

- Excitation/Emission: 561 nm / 570-610 nm for TMRE [28] [30].

- Use low laser power (1-5%) and resolution (256 x 256) to minimize photobleaching and phototoxicity [28].

- Acquire a time-series to establish a stable baseline (e.g., 5-10 images over 2-5 minutes).

Pharmacological Validation:

- Apply 1 μM FCCP (uncoupler) at the end of the baseline acquisition. A successful experiment shows a rapid and significant decrease in TMRE fluorescence intensity, confirming the ΔΨm-dependent nature of the signal [28].

Quantitative Analysis:

- Region of Interest (ROI): Select ROIs over mitochondrial regions or entire cell bodies [28].

- Background Subtraction: Measure fluorescence intensity in a cell-free region and subtract this value from the cellular ROI intensities [28].

- Normalization: Normalize fluorescence intensity (F) to the average baseline fluorescence (F₀) for each ROI using the formula: ΔF/F₀ (%) = (F - F₀)/F₀ × 100 [28].

- Heterogeneity Analysis: Calculate the coefficient of variation (CV) from single-cell measurements to assess population heterogeneity [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for ΔΨm Research

| Reagent / Assay Kit | Function / Specificity | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| TMRE (Tetramethylrhodamine Ethyl Ester) | Potentiometric ΔΨm indicator [28] [30]. | Use in non-quenching mode (low nM range). Fluorescence intensity proportional to ΔΨm. |

| TMRE-Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay Kit | Complete kit including TMRE dye and optimized buffer [31]. | Streamlines workflow; includes protocols for flow cytometry. |

| JC-1 | Rationetric ΔΨm indicator; forms J-aggregates (red) in high ΔΨm [23]. | More complex signal interpretation due to aggregation; can be affected by mitochondrial morphology. |

| FCCP / CCCP | Proton ionophores; positive control for complete ΔΨm depolarization [28]. | Use at 0.5-1 μM for intact cells. CCCP may have broader cellular effects than FCCP. |

| Oligomycin | ATP synthase inhibitor; positive control for ΔΨm hyperpolarization [28] [30]. | Use at 1-2 μg/ml. Hyperpolarization is due to inhibition of proton consumption by ATP synthase. |

| H2DCF-DA | Cell-permeant indicator for general oxidative stress/ROS [28]. | Useful for parallel assessment of ROS, a key parameter linked to ΔΨm [24] [28]. |

| MitoTracker Probes (e.g., Deep Red) | Covalent mitochondrial labels; independent of ΔΨm for long-term tracking [23]. | Ideal as a morphological reference stain for mitochondrial location and mass. |

The analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential using TMRE is an indispensable tool for probing cellular health and function across diverse research fields. The precise protocols and contextual data provided in this application note equip researchers to effectively apply this technique. As evidenced, ΔΨm serves as a critical node linking metabolic state to fundamental cellular outcomes in neurodegeneration, cancer, and drug-induced toxicity, making its accurate measurement vital for advancing both basic science and therapeutic development.

A Practical Guide to TMRE Assays: From Basic Protocols to Advanced High-Throughput Applications

Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) is the electrical potential difference across the inner mitochondrial membrane, a key parameter reflecting mitochondrial health and cellular energy status [3]. It is generated by the proton pumps of the electron transport chain and is essential for ATP production through oxidative phosphorylation [3]. Dysregulation of ΔΨm is a hallmark of cellular dysfunction and is implicated in various diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders, cancer, and metabolic syndromes [3] [32].

Tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) is a cell-permeant, cationic, fluorescent dye that readily accumulates in active mitochondria due to their relative negative charge [3]. The intensity of TMRE fluorescence is directly proportional to the ΔΨm. Depolarized or inactive mitochondria exhibit a decreased membrane potential and fail to sequester TMRE, resulting in a diminished fluorescence signal [3] [33]. This property makes TMRE an ideal probe for monitoring changes in mitochondrial function in live cells across various experimental platforms, including flow cytometry, fluorescence microscopy, and microplate readers [3].

Principle of TMRE Assay and Key Signaling Pathways

The TMRE assay leverages the electrochemical gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane. The positively charged TMRE molecule is electrophoretically taken up into the mitochondrial matrix in a manner dependent on the membrane potential. In healthy, polarized mitochondria, this results in the accumulation of the dye and a strong fluorescent signal. A loss of ΔΨm, which can occur during cellular stress or the early stages of apoptosis, prevents this accumulation, leading to a reduction in fluorescence [3] [34].

The following diagram illustrates the core principle of the TMRE assay and its connection to key cellular pathways, culminating in the experimental readout.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of the TMRE assay requires careful preparation of reagents and access to appropriate instrumentation. The table below details the core components of the research toolkit.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for TMRE Assay

| Item | Function/Description | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TMRE | Cell-permeant, cationic fluorescent dye that accumulates in polarized mitochondria. | Often supplied as a stock solution in DMSO [3] [11]. |

| FCCP | Proton ionophore uncoupler; used as a positive control to dissipate ΔΨm and validate the assay [3]. | Carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone [3]. |

| Assay Buffers | For washing cells and diluting dyes (e.g., PBS). PBS with 0.2% BSA is recommended for washing steps to reduce background [3]. | Krebs-Ringer-Hepes (KRH) buffer can be used for calcium-related studies [32]. |

| Live Cells | The assay is exclusively for use with live, unfixed cells [3]. | Adherent (e.g., HeLa) or suspension (e.g., Jurkat) cells [3]. |

| Detection Instruments | Equipment for measuring fluorescence signal. | Fluorescent microplate reader, microscope, or flow cytometer [3] [35]. |

Core Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed, step-by-step methodologies for assessing ΔΨm using TMRE across three common platforms.

General Staining Protocol

The foundational staining procedure is consistent across all detection methods and must be optimized for specific cell types.

- Preparation of Staining Solution: Dilute TMRE in pre-warmed culture medium to the desired working concentration. A typical working range is 50-500 nM [3] [32]. Note: Using TMRE at concentrations <200 nM is recommended to avoid fluorescence quenching and artifactual signals [32].

- Positive Control Preparation: Treat control cell samples with the uncoupler FCCP (e.g., 1-100 µM) for 10 minutes at 37°C prior to and during TMRE staining to depolarize mitochondria [3] [34].

- Staining Incubation: Remove culture medium from cells and add the TMRE staining solution. Incubate for 15-30 minutes at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ incubator [3] [32].

- Washing: After incubation, carefully pellet suspension cells or remove the staining solution from adherent cells. Gently wash the cells 1-3 times with PBS, preferably containing 0.2% BSA, to remove excess, non-specific dye [3] [32].

- Immediate Analysis: Resuspend or overlay the cells with fresh culture medium or PBS and proceed immediately with analysis on your chosen platform. Do not fix the cells, as this will disrupt the potential-dependent staining [3] [34].

Platform-Specific Protocols and Parameters

The following table summarizes the critical instrument settings and procedural notes for each detection method.

Table 2: Platform-Specific Parameters for TMRE Analysis

| Parameter | Flow Cytometry | Fluorescence Microscopy | Microplate Reader |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Steps | 1. Prepare single-cell suspension after staining [3].2. Resuspend in PBS for analysis.3. Acquire at least 10,000 events per sample. | 1. Culture cells on glass-bottom dishes or chamber slides [35].2. After staining and washing, add a small volume of fresh medium for imaging.3. Image promptly to maintain cell viability. | 1. Seed cells in sterile, clear-bottom, black-walled microplates [35].2. Include blanks (wells with medium but no cells) for background subtraction. |

| Excitation/Emission | 488 nm laser excitation; detection with a 575 nm filter (e.g., PE channel) [3] [35]. | Standard TRITC filter set [11]. Ex/Em ~549/575 nm [3]. | Ex/Em = 549/575 nm [3]. |

| Data Output | Fluorescence intensity per cell (histograms). Enables quantification of heterogeneous responses within a population [3] [34]. | Qualitative and spatial information on mitochondrial localization and morphology within single cells [3] [32]. | Mean Fluorescent Intensity (MFI) per well, providing a population-average measurement [3]. |

| Critical Validation | Compare fluorescence intensity histograms of untreated vs. FCCP-treated cells. A clear left-shift (signal decrease) should be observed in the FCCP-treated sample [3] [34]. | Visually confirm loss of punctate mitochondrial staining and overall signal reduction in FCCP-treated cells compared to the bright, granular pattern in healthy cells [3]. | The MFI of FCCP-treated controls should be significantly lower than that of untreated cells. Data is often presented as MFI +/- standard deviation [3]. |

The workflow for all three platforms is consolidated in the following experimental roadmap.

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

Even with a robust protocol, researchers may encounter challenges. The table below outlines common issues and recommended solutions.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for TMRE Assays

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background / Nonspecific Signal | Incomplete washing of excess dye [32]. | Increase the number of washes with PBS/0.2% BSA [32]. |

| TMRE concentration is too high [32]. | Titrate the TMRE dose. Use lower concentrations (e.g., 50-100 nM) and avoid exceeding 200 nM to prevent quenching [32]. | |

| Weak or No Signal | Loss of ΔΨm due to cell death or excessive stress. | Check cell viability and health. Ensure cultures are not over-confluent. |

| Photobleaching from prolonged light exposure [32]. | Minimize light exposure during staining and analysis; use lower laser power or shorter exposure times [32]. | |

| Inconsistent Results | Inadequate FCCP control validation. | Always include an FCCP-treated control. If this control does not show a strong signal decrease, the assay is not functioning correctly [3] [32]. |

| Dye precipitation or degradation. | Ensure TMRE stock is properly stored at -20°C and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. Centrifuge staining solution before use if precipitation is suspected. | |

| Poor Mitochondrial Localization (Microscopy) | Probe accumulation in non-mitochondrial compartments [32]. | Confirm mitochondrial localization by co-staining with a validated mitochondrial marker (e.g., MitoTracker) [32]. |

Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) is a critical indicator of mitochondrial health and cellular viability, serving as a key parameter in fields ranging from fundamental cell biology to drug development. Tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester (TMRE) is a cell-permeant, cationic dye that accumulates in active mitochondria in a ΔΨm-dependent manner, making it a vital tool for assessing mitochondrial function. The reliability of TMRE-based assays, however, is highly dependent on the meticulous optimization of several key parameters. This application note provides a detailed framework for optimizing TMRE concentration, incubation time, and cell density to ensure robust, reproducible, and accurate assessment of ΔΨm. Proper optimization is not merely a technical exercise; it is fundamental to generating high-quality data that can accurately inform on mitochondrial responses to pharmacological treatments or genetic modifications, thereby supporting critical decisions in the research and development pipeline [4].

The Critical Role of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

The mitochondrial membrane potential, generated by the electron transport chain (ETC), represents approximately 80% of the proton motive force (Δp) that drives ATP synthesis. Maintaining ΔΨm is essential for mitochondrial functions, including protein import, ion homeostasis, and ATP production [4] [10]. Notably, ΔΨm is not a static metric. It dynamically reflects the balance between its generation by the ETC and its consumption primarily by ATP synthase. This means that a change in ΔΨm must be interpreted carefully: a decrease could indicate either a loss of ETC function or an increase in ATP demand and turnover [4].

Hyperpolarization and Depolarization: While mitochondrial depolarization is a well-established hallmark of dysfunction and a trigger for mitophagy, chronic mitochondrial hyperpolarization is increasingly recognized for its profound cellular effects. Research using IF1-knockout cell models has demonstrated that sustained hyperpolarization can trigger extensive transcriptional reprogramming, alter nuclear DNA methylation, and remodel phospholipids, influencing processes from epigenetics to cell cycle progression [10]. This underscores that both increases and decreases in ΔΨm can be biologically significant, necessitating precise and reliable measurement techniques.

TMRE as a Measurement Tool: TMRE is a potentiometric dye that distributes across the mitochondrial membrane according to the Nernst equation. In healthy, polarized mitochondria, the negatively charged interior attracts and concentrates the cationic TMRE, resulting in intense fluorescence. A loss of ΔΨm prevents this accumulation, leading to a diffuse distribution of the dye in the cytosol and a corresponding decrease in fluorescent signal. This property makes TMRE an excellent indicator of mitochondrial function, but its accurate application requires careful protocol standardization [11].

Optimizing Key Parameters for TMRE Staining

Successful ΔΨm measurement with TMRE hinges on a balanced interplay between dye concentration, incubation time, and cell density. The following section provides optimized parameters and a structured protocol to guide researchers.

Parameter Optimization Guidelines

Table 1: Key Parameters for TMRE Staining Optimization

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Key Considerations | Impact of Sub-Optimal Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMRE Working Concentration | 150 - 500 nM | A common effective concentration is 250 nM [11]. The optimal concentration should be determined empirically for each cell type. | Too High: Can induce mitochondrial toxicity and uncoupling.Too Low: Results in a weak fluorescent signal and poor resolution. |

| Incubation Time | 15 - 30 minutes | A standard incubation time is 30 minutes at 37°C [11]. Ensure consistent timing across all samples. | Too Short: Incomplete dye loading and underestimation of ΔΨm.Too Long: Potential for dye toxicity and artifactual results. |

| Cell Density | 50 - 80% confluency | Ensure cells are healthy and not over-confluent to avoid nutrient depletion and stress-induced changes in ΔΨm. | Too Dense: Leads to nutrient competition, contact inhibition, and altered metabolism.Too Sparse: Inconsistent imaging fields and higher well-to-well variability. |

| Post-Staining Wash | 2-3 washes with clear buffer | Use pre-warmed PBS or other clear saline-based buffer. Image promptly after washing. | Insufficient Washing: High background fluorescence from unincorporated dye.Excessive Washing/Delays: Risk of dye leakage from mitochondria. |

Detailed Staining Protocol

This protocol is designed for a single well of a 6-well plate or a 35 mm dish. Scale volumes accordingly [11].

Preparation of Staining Solution

- Prepare a 10 mM stock solution of TMRE in DMSO and store it at -20°C.

- On the day of the experiment, prepare an intermediate dilution (e.g., 50 µM) in complete cell culture medium.

- Prepare the final working staining solution (e.g., 250 nM) by diluting the intermediate stock in pre-warmed complete medium. Protect from light.

Cell Staining

- Culture cells according to standard practices, ensuring they are at an optimal density (e.g., 50-80% confluency) at the time of staining.

- Aspirate the culture medium from the live cells.

- Add the prepared TMRE staining solution to the cells.

- Incubate for 30 minutes in a 37°C incubator (5% CO₂), protected from light.

Washing and Imaging

- After incubation, carefully aspirate the TMRE staining solution.

- Gently wash the cells 2-3 times with pre-warmed PBS or another clear, buffered saline solution.

- After the final wash, add a small volume of pre-warmed clear buffer or FluoroBrite DMEM to the cells.

- Image the cells immediately using a fluorescence microscope equipped with a TRITC (or Cy3) filter set. For live-cell imaging, maintain the cells at 37°C during image acquisition.

Validation and Controls

Including appropriate controls is non-negotiable for validating the specificity of the TMRE signal.

- Depolarization Control: Treat a separate sample of cells with a mitochondrial uncoupler such as FCCP (1-10 µM) or a combination of oligomycin (1 µM) and antimycin A (1 µM) for 15-30 minutes prior to and during TMRE staining. A valid assay will show a marked reduction in punctate mitochondrial fluorescence in the control-treated sample [4].

- Viability Control: Always confirm cell viability under the chosen staining conditions, as excessive TMRE concentrations or prolonged incubation can be toxic.

- Quenching vs. Non-Quenching Mode: Be aware of the operational mode. The recommended concentrations (e.g., 250 nM) are typically for the non-quenching mode, where fluorescence intensity is proportional to ΔΨm. High, self-quenching concentrations require a different interpretation and are not recommended for standard assays [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for TMRE-based ΔΨm Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TMRE | Potentiometric fluorescent dye used to measure mitochondrial membrane potential. | Tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester; supplied as a powder, typically made into a 10 mM stock in DMSO [11]. |

| FCCP / CCCP | Protonophore uncouplers; used as a key validation control to dissipate ΔΨm. | Confirms that TMRE signal is ΔΨm-dependent. A working concentration is often 1-10 µM. |

| Oligomycin | ATP synthase inhibitor; used in control experiments to manipulate ΔΨm. | Inhibits the forward activity of ATP synthase, which can lead to a hyperpolarization of the membrane [4] [10]. |

| Cell Permeabilizer | For assays on isolated mitochondria or controlled substrate conditions. | e.g., Digitonin. Used in conjunction with substrates like succinate to energize mitochondria [10]. |

| MitoTracker Green (MTG) | A ΔΨm-independent mitochondrial mass dye. | Useful for normalizing TMRE fluorescence to mitochondrial content, helping to distinguish changes in potential from changes in mass [10]. |

| Live-Cell Imaging Medium | A clear, low-fluorescence buffer for maintaining cells during imaging. | e.g., FluoroBrite DMEM or HBSS. Helps reduce background fluorescence and maintains physiological pH. |

Visualizing the Workflow and Key Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the core principles of the TMRE assay and the experimental workflow.

Diagram 1: TMRE Experimental Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key steps for a standard TMRE staining experiment, from sample preparation to data analysis.

Diagram 2: TMRE Signal Response to ΔΨm. This diagram illustrates the fundamental principle of how TMRE distribution and fluorescence signal change in response to the health status of the mitochondria.

Integrated Analysis: Connecting ΔΨm to Broader Cellular Phenotypes

Changes in ΔΨm do not occur in isolation. Integrating TMRE-based measurements with other cellular assays provides a systems-level understanding of how mitochondrial status influences cell fate. For instance, a decrease in cell number observed in a pharmacological screen could be due to either increased cell death or decreased proliferation. A multiparametric flow cytometry approach that simultaneously measures ΔΨm (using JC-1, a dye analogous to TMRE), apoptosis (annexin V/PI), and proliferation (BrdU or CellTrace Violet) can dissect these mechanisms [12]. This integrated workflow can reveal, for example, that a drug-induced mitochondrial depolarization triggers the intrinsic apoptosis pathway, leading to increased cell death. Furthermore, changes in ΔΨm can modulate nuclear gene expression through mechanisms like phospholipid remodeling, creating a feedback loop that influences the cell's long-term adaptive response [10]. Therefore, TMRE staining serves as a critical entry point for a deeper, more comprehensive investigation into cellular bioenergetics and health.

Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) is a key indicator of cellular health, serving as a critical parameter for evaluating mitochondrial function. The electrochemical gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane drives ATP production and is essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis [37] [4]. A significant loss of ΔΨm is an early event in apoptosis and other pathological conditions, rendering cells depleted of energy with subsequent death [28] [7]. Fluorescent dyes such as TMRE (tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester) are widely used to monitor ΔΨm in live cells. However, the specificity of these dyes for ΔΨm-dependent staining must be rigorously validated using appropriate controls. This application note details the use of mitochondrial uncouplers FCCP (carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone) and CCCP (carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone) as essential controls to confirm that observed fluorescence changes genuinely reflect alterations in ΔΨm rather than non-specific artifacts [3] [28].

Theoretical Background: The Role of FCCP/CCCP in Validating ΔΨm Measurements

Mechanism of Protonophore Action

FCCP and CCCP are protonophores that function as mitochondrial uncouplers by dissipating the proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane. These lipophilic weak acids shuttle protons across the mitochondrial membrane, effectively collapsing the electrochemical gradient that constitutes ΔΨm [3] [4]. This action decouples substrate oxidation from ATP synthesis, leading to maximum electron transport chain activity without ATP production. When used as positive controls in TMRE staining experiments, FCCP/CCCP treatment should result in a marked decrease in TMRE fluorescence, confirming that the dye accumulation is ΔΨm-dependent [3] [28].

Importance of Experimental Controls

Without proper controls, fluorescence changes attributed to ΔΨm may actually result from non-specific factors including dye loading variability, changes in mitochondrial mass, plasma membrane potential alterations, or non-specific binding. The inclusion of FCCP/CCCP controls provides a critical benchmark for distinguishing ΔΨm-specific staining from these confounding factors [37] [4]. This validation is particularly important when investigating the effects of novel compounds on mitochondrial function in drug development contexts, where accurate assessment of mitochondrial toxicity is essential [14].

TMRE Staining Protocol with FCCP/CCCP Controls

Principle of TMRE Staining

TMRE is a cell-permeant, cationic, red-orange fluorescent dye that accumulates in active mitochondria due to their relative negative charge [3] [38]. The dye enters mitochondria in a membrane potential-dependent manner and is retained at higher concentrations in polarized mitochondria. Depolarized or inactive mitochondria exhibit decreased membrane potential and fail to sequester TMRE, resulting in reduced fluorescence intensity [3] [7]. TMRE is suitable for quantitative measurement of membrane potential using the Nernst equation and can be applied with various detection platforms including fluorescence microscopy, flow cytometry, and microplate fluorometry [38].

Reagent Preparation

Staining Procedure for Adherent Cells

- Cell Preparation: Plate adherent cells in appropriate culture vessels (e.g., 96-well plates, chamber slides) and culture until 70-90% confluent [3] [39].

- Positive Control Setup: Add FCCP or CCCP to designated positive control wells at final concentrations typically ranging from 1-50 μM and incubate for 10-30 minutes at 37°C [3] [28].

- TMRE Loading: Prepare TMRE working solution in pre-warmed culture medium or buffer at concentrations typically between 50-500 nM [3] [28]. Remove culture medium from cells and replace with TMRE-containing solution.

- Incubation: Incubate cells with TMRE for 15-45 minutes at 37°C protected from light [3] [35].

- Washing: Remove TMRE solution and wash cells 1-2 times with PBS or assay buffer to remove excess dye [3] [39].

- Imaging/Analysis: Immediately analyze samples using an appropriate detection platform.

Staining Procedure for Suspension Cells