Troubleshooting Nonspecific Cleavage in Caspase Substrates: A Researcher's Guide to Enhancing Specificity and Data Reliability

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals facing the common yet challenging issue of nonspecific cleavage when working with caspase substrates.

Troubleshooting Nonspecific Cleavage in Caspase Substrates: A Researcher's Guide to Enhancing Specificity and Data Reliability

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals facing the common yet challenging issue of nonspecific cleavage when working with caspase substrates. It covers the foundational principles of caspase biology and substrate recognition, explores advanced methodological approaches for detecting cleavage, details systematic troubleshooting and optimization strategies for experimental protocols, and outlines rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing current research and proteomic findings, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to accurately interpret caspase activity, minimize artifactual results, and enhance the reliability of data in apoptosis research, drug discovery, and disease mechanism studies.

Understanding Caspase Biology and the Roots of Nonspecific Cleavage

Foundational Concepts: Caspase Classification and Function

What are the main functional classes of caspases? Caspases are typically categorized into three main functional groups based on their primary roles in apoptosis, inflammation, and other cellular processes [1]:

Table 1: Functional Classification of Human Caspases

| Functional Class | Caspase Members | Primary Role |

|---|---|---|

| Initiator (Apoptotic) | Caspase-2, -8, -9, -10 | Initiate apoptosis; activated by dimerization in multiprotein complexes (e.g., DISC, apoptosome) [2] [1]. |

| Executioner (Apoptotic) | Caspase-3, -6, -7 | Execute apoptosis; cleave hundreds of cellular substrate proteins, leading to cell dismantling [3] [4]. |

| Inflammatory | Caspase-1, -4, -5, -11 (mouse), -12 | Mediate inflammation and pyroptosis; process pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β [2] [1]. |

How does the activation of initiator and executioner caspases differ? The activation mechanisms for initiator and executioner caspases follow a hierarchical cascade [1]:

- Initiator Caspases (e.g., Caspase-8, -9): Are activated by dimerization within large multiprotein complexes such as the Death-Inducing Signaling Complex (DISC) for caspase-8 or the Apoptosome for caspase-9. This dimerization allows them to undergo auto-proteolytic cleavage [1].

- Executioner Caspases (e.g., Caspase-3, -7): Exist as inactive dimers in living cells. They are activated by cleavage by an upstream initiator caspase. For example, caspase-8 or -9 cleaves caspase-3, which results in the formation of the active enzyme composed of two large and two small subunits [3] [1].

This activation cascade ensures tight regulation of the cell death process.

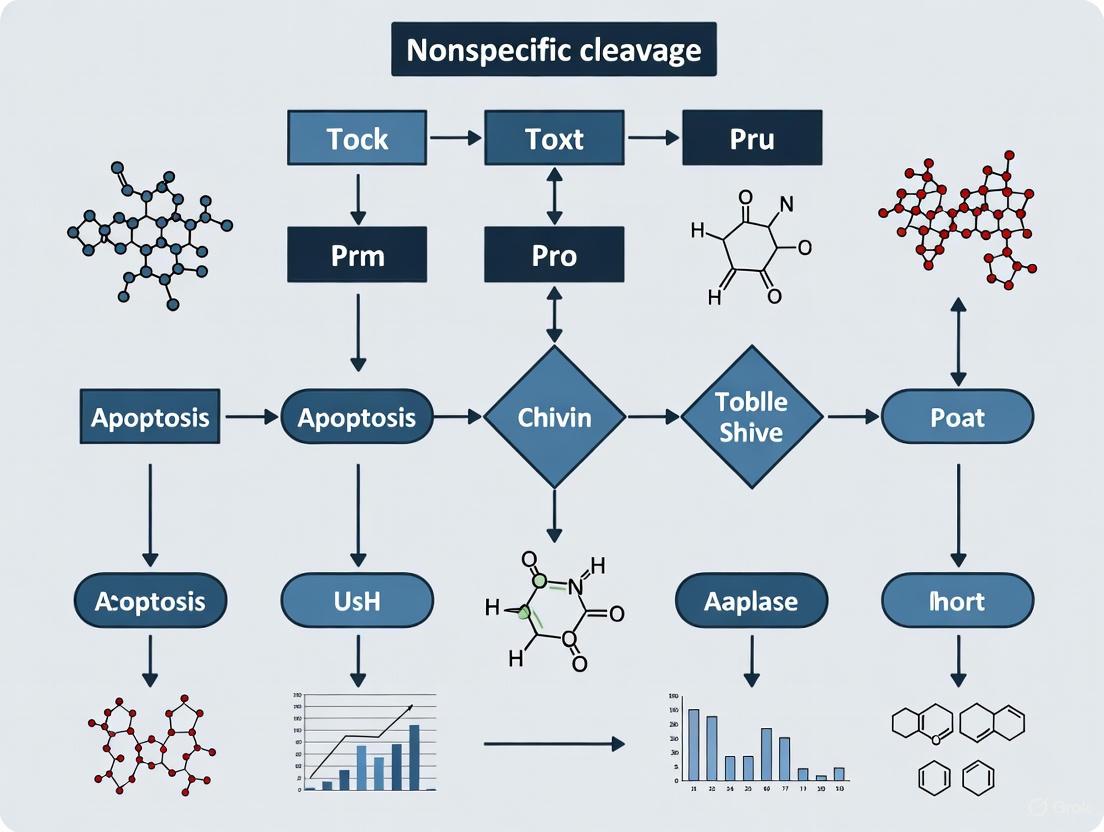

Figure 1: Hierarchical Activation Cascade of Apoptotic Caspases.

The Core Challenge: Defining Caspase Substrate Specificity

What defines an ideal caspase cleavage motif? Caspases are cysteine-dependent aspartyl-directed proteases. This means they cut their substrate proteins specifically after an aspartic acid (Asp or D) residue [3]. This aspartate is designated the P1 residue. The amino acids preceding P1 in the substrate (P2, P3, P4, etc.) determine which caspase recognizes and cleaves the site most efficiently [3].

The general recognition motif is a tetrapeptide, denoted as P4-P3-P2-P1, where P1 is always Asp (D) [3]. While the presence of an Asp is necessary, it is not sufficient for cleavage; the surrounding sequence and the structural accessibility of the site are critical.

Why do I observe nonspecific cleavage in my experiments? Nonspecific cleavage, where a substrate is cut by a caspase it is not intended for, is a common experimental challenge. The primary reason is the significant overlap in the cleavage motif preferences of different caspases [5].

Research comparing the activity of caspases on short peptide-based substrates revealed that caspase-3, in particular, can cleave most substrates more efficiently than the caspases to which those substrates are reportedly specific [5]. For instance, a substrate designed to be specific for caspase-9 might also be efficiently cleaved by the more promiscuous caspase-3 if it is present. This promiscuity means that using peptide-based substrates and inhibitors to define relevant caspases and pathways in complex systems can be problematic [5].

Table 2: Characteristic Substrate Motif Preferences for Key Caspases [3] [6]

| Caspase | Primary Function | Preferred Tetrapeptide Motif (P4-P3-P2-P1) |

|---|---|---|

| Caspase-3 | Executioner | DEXD (where X is any amino acid) |

| Caspase-7 | Executioner | Similar to caspase-3 (DEVD) |

| Caspase-6 | Executioner | VEID |

| Caspase-8 | Initiator | LETD, IETD |

| Caspase-9 | Initiator | LEHD |

| Caspase-1 | Inflammatory | WEHD, YVAD |

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Nonspecific Cleavage

FAQ 1: My substrate is being cleaved by multiple caspases in a cell lysate. How can I identify the specific caspase responsible? This is a classic problem arising from overlapping substrate specificities [5]. A multi-pronged experimental approach is recommended:

- Immunodepletion: Prior to activating apoptosis in a cell-free system, immunodeplete specific caspases (e.g., caspase-3) from the lysate. If the cleavage event is abolished upon depletion of a particular caspase, it strongly indicates that caspase is responsible [5].

- Use of Selective Inhibitors with Caution: While commercially available caspase inhibitors (e.g., Z-VAD-FMK, pan-caspase inhibitor) are useful, many peptide-based inhibitors designed for individual caspases lack absolute selectivity [5]. A purported caspase-9 inhibitor might also potently inhibit caspase-3. Always consult the manufacturer's data on inhibitor cross-reactivity.

- Genetic Knockdown/Knockout: Using cell lines with genetic deficiencies in specific caspases (e.g., caspase-9 deficient Jurkat cells) provides the most definitive evidence [5] [7]. If the cleavage is lost in the knockout cell line, the absent caspase is essential for that event.

FAQ 2: My peptide-based caspase inhibitor is not providing specific inhibition. What are my alternatives? The limited selectivity of short peptide inhibitors is a well-documented issue [5]. To address this:

- Validate with Multiple Inhibitors: Use a panel of inhibitors with different specificities and compare the results. No single inhibitor should be relied upon.

- Consider Newer Inhibitor Chemotypes: The field is moving beyond simple peptide substrates. For example, a novel pan-caspase inhibitor, Z-AEAD-FMK, was recently developed based on the identification of a new caspase cleavage motif (AEAD), and it has shown efficacy in inhibiting multiple caspases [8]. Explore recent literature for novel inhibitory compounds.

- Focus on Genetic Approaches: As above, using CRISPR/Cas9-generated knockout cells or siRNA-mediated knockdown provides a genetic validation that is independent of pharmacological inhibitors.

FAQ 3: How can I comprehensively identify the specific substrates of a single caspase, like caspase-9, without interference from other caspases? Advanced proteomic techniques are the gold standard for this. The following protocol outlines a reverse N-terminomics approach, which was used to identify 124 specific substrates for caspase-9, de-orphanizing its function beyond just activating caspase-3 [7].

Experimental Protocol: Reverse N-Terminomics for Caspase Substrate Identification [7]

Objective: To identify direct protein substrates of a specific caspase (e.g., caspase-9) in a complex native lysate.

Key Reagents & Materials:

- Cell Line: Use a caspase-9 deficient cell line (e.g., Jurkat JMR) to eliminate background activation of the endogenous caspase cascade [7].

- Purified Recombinant Caspase: The caspase of interest (e.g., active caspase-9).

- Specific Executioner Inhibitor: Ac-DEVD-fmk to inhibit any potential trace activity of caspase-3/-7, ensuring cleavages are directly from the added caspase and not a downstream executioner [7].

- Protease Inhibitor Cocktail: To inhibit non-caspase proteases during cell lysis.

- Subtiligase and Biotin-Ester Peptide Tag: An engineered enzyme for chemoenzymatic tagging of neo-N-terminal generated by proteolysis.

- NeutrAvidin Beads: For affinity purification of biotinylated peptides.

- Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): For identification and sequencing of captured peptides.

Workflow:

Figure 2: Workflow for Reverse N-Terminomics Substrate Identification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Caspase Specificity Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Caspase-Deficient Cell Lines (e.g., Caspase-9 KO Jurkat) [7] | Genetically defines the role of a specific caspase without pharmacological inhibition. | Eliminates compensatory activation of other caspases. |

| Ac-DEVD-fmk (or similar) [7] | Selective inhibitor of executioner caspases (-3/-7). | Critical in initiator caspase assays (e.g., caspase-9) to block downstream amplification. |

| Z-VAD-FMK | Broad-spectrum, pan-caspase inhibitor. | Useful as a positive control to confirm caspase-dependent processes. |

| Z-AEAD-FMK [8] | Novel pan-caspase inhibitor based on the AEAD motif. | Represents a new class of inhibitors; broad activity against caspases-1, -3, -6, -7, -8, -9. |

| Recombinant Active Caspases | For in vitro cleavage assays and biochemical characterization. | Verify direct cleavage of a putative substrate, excluding indirect cellular effects. |

| Selective Substrate Panels (e.g., DEVD, VEID, LEHD) | To profile caspase activity in samples. | Be aware of significant cross-reactivity; caspase-3 can cleave many "specific" substrates [5]. |

| Subtiligase N-Terminomics Kit | For global, unbiased identification of protease substrates [7]. | Powerful for discovery but requires specialized expertise in proteomics and MS. |

Caspases are a family of cysteine-dependent aspartate-specific proteases that play critical roles in regulating programmed cell death (apoptosis and pyroptosis) and inflammation [9] [10]. These enzymes function as crucial molecular switches in cellular fate decisions, with their activity determined by specific interactions at their active sites and auxiliary exosite regions [11] [12]. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for researchers investigating caspase substrate specificity, particularly when troubleshooting unexpected cleavage events in experimental settings.

The fundamental catalytic mechanism of caspases involves a conserved cysteine-histidine catalytic dyad that performs nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl carbon of the peptide bond immediately after an aspartic acid residue at the P1 position [13]. This action leads to the formation of an unstable tetrahedral intermediate anion, which is stabilized by an oxyanion hole formed by hydrogen bonding from backbone nitrogens of the conserved G238, the catalytic cysteine (C285), and the carbonyl oxygen of the cleaved aspartate [13].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Core Concepts

Q1: What defines the canonical substrate specificity of caspases?

Caspases primarily cleave their substrates after aspartic acid residues, with additional specificity determined by the amino acids at positions P4-P2 relative to the cleavage site [4] [14]. Each caspase has preferred recognition motifs, though significant overlap exists between family members. The substrate recognition sequences are described by the nomenclature P4-P3-P2-P1↓P1', where the cleavage occurs between P1 and P1' positions [14].

Q2: Why might my experiments show unexpected or nonspecific caspase cleavage?

Several factors can contribute to unexpected cleavage events:

- Cross-family reactivity: Apoptotic caspases can sometimes drive inflammatory cell death pathways, leading to cleavage of unexpected substrates [9] [11]

- Exosite interactions: Engagement of substrate regions distant from the active site can influence cleavage specificity [12]

- Post-translational modifications: Phosphorylation near cleavage sites can dramatically alter caspase recognition [15]

- Overexpression artifacts: Non-physiological caspase concentrations in experimental systems can lead to promiscuous cleavage [4]

Q3: How do exosite interactions complement active site recognition?

Exosites provide additional binding interfaces that enhance substrate specificity and catalytic efficiency beyond what is possible through active site interactions alone. The crystal structure of caspase-1 bound to full-length gasdermin D reveals a dual-interface engagement mechanism where the active site processes the cleavage linker while an exosite formed by the caspase-1 L2 and L2' loops binds a hydrophobic pocket within the gasdermin D C-terminal domain [12]. This exosite interface endows an additional recruitment function that contributes to substrate specificity.

Q4: What technical approaches can validate putative caspase substrates?

A combination of methods provides the most robust validation:

- In vitro cleavage assays with purified components [16]

- N-terminomic strategies like Terminal Amine Isotopic Labeling of Substrates (TAILS) [15]

- Mass spectrometry-based degradome analysis [4] [14]

- Structural studies (crystallography, NMR) to map interaction interfaces [12]

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Problem: Nonspecific Substrate Cleavage inIn VitroAssays

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Table: Troubleshooting Nonspecific Cleavage

| Problem Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Caspase contamination | Test individual caspase preparations separately; use selective inhibitors | Repurify caspase stocks; include specificity controls in assays |

| Non-physiological enzyme concentration | Perform dilution series to establish concentration-dependent effects | Use lowest effective caspase concentration; mimic physiological conditions |

| Missing regulatory factors | Compare cleavage in lysates vs purified systems | Add back cellular fractions; include natural caspase inhibitors |

| Phosphorylation status | Treat with phosphatases/kinases before assay [15] | Control phosphorylation state through buffer conditions |

Problem: Inconsistent Cleavage Efficiency Between Different Substrates

Investigation Strategy:

- Determine kinetic parameters (Km, kcat) for problematic substrates

- Check for post-translational modifications that might inhibit cleavage [15]

- Investigate potential exosite interactions through truncation mutants

- Test whether phosphorylation at P4, P2, or P1' positions blocks cleavage [15]

Experimental Approach: Systematically analyze the effect of phosphoserine throughout the entirety of caspase recognition motifs using synthetic peptides. Research demonstrates that phosphorylation generally exerts an inhibitory effect on caspase cleavage, even at residues outside the classical consensus motif [15].

Caspase Classification and Substrate Preference

Structural and Functional Classification

Caspases are traditionally categorized based on function and domain architecture:

Substrate Recognition Profiles

Table: Caspase Substrate Preference Motifs [4] [14]

| Caspase | Peptide Substrate Preference | Protein Substrate Consensus | Primary Cellular Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caspase-1 | WEHD | YVHD/FESD | Pyroptosis, inflammation |

| Caspase-2 | VDVAD | XDEVD | Apoptosis initiation |

| Caspase-3 | DEVD | DEVD | Apoptosis execution |

| Caspase-4 | (W/L)EHD | Not fully characterized | Non-canonical pyroptosis |

| Caspase-5 | (W/L)EHD | Not fully characterized | Non-canonical pyroptosis |

| Caspase-6 | VQVD | VEVD | Apoptosis execution |

| Caspase-7 | DEVD | DEVD | Apoptosis execution |

| Caspase-8 | LETD | XEXD | Extrinsic apoptosis initiation |

| Caspase-9 | (W/L)EHD | Not fully characterized | Intrinsic apoptosis initiation |

| Caspase-10 | LEHD | LEHD | Extrinsic apoptosis initiation |

Experimental Protocols for Substrate Verification

Purpose: To confirm putative caspase substrates identified through proteomic screens as bona fide caspase targets.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Purified recombinant caspase of interest

- Putative substrate protein (radiolabeled or tagged)

- Caspase assay buffer: 0.1% CHAPS, 20 mM PIPES (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl

- Protease inhibitors (leupeptin, PMSF, pepstatin A, aprotinin)

- Phosphatase inhibitors (NaF, microcystin, sodium orthovanadate) [15]

- SDS-PAGE equipment

- Detection system (Western blot, radiography, or fluorescence)

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Generate radiolabeled or epitope-tagged versions of putative substrates using in vitro transcription/translation systems.

- Reaction Setup: Incubate substrate with purified caspase in assay buffer. Include controls without caspase and with caspase pre-treated with pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk.

- Time Course: Perform reactions for varying durations (0-120 minutes) at 37°C.

- Termination: Stop reactions by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer or caspase inhibitors.

- Analysis: Resolve proteins by SDS-PAGE and detect cleavage products via autoradiography, Western blotting, or other detection methods.

- Validation: Confirm cleavage by appearance of predicted fragment sizes and inhibition by caspase-specific inhibitors.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Include positive control substrates with known cleavage patterns

- Test multiple caspase:substrate ratios to establish optimal conditions

- Consider phosphorylation status by including phosphatase treatments [15]

Purpose: Unbiased identification of caspase cleavage sites in complex proteomes.

Workflow Overview:

Key Steps:

- Prepare cell lysates with protease and phosphatase inhibitors

- Treat aliquots with/without λ phosphatase to modulate phosphorylation state

- Incubate with caspases (50-5000 nM) for 1 hour at 37°C

- Terminate reactions with z-VAD-fmk inhibitor

- Process samples using TAILS workflow:

- Dimethylate primary amines with isotopic labels

- Digest with trypsin

- Remove internal tryptic peptides with HPG-ALDII polymer

- Analyze N-terminome by LC-MS/MS

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagents for Caspase Mechanism Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Caspase Inhibitors | z-VAD-fmk (pan-caspase), VX-765 (caspase-1), Emricasan (caspase-2,3) [9] | Specificity controls, pathway validation |

| Activity Reporters | Ac-DEVD-AFC (caspase-3/7), Ac-LEHD-AFC (caspase-9), Ac-WEHD-AFC (caspase-1) [17] | Kinetic measurements, inhibitor screening |

| Phosphatase Treatments | λ phosphatase [15] | Investigating phosphorylation-dependent cleavage regulation |

| Tagging Systems | GST, His-tags, fluorescent proteins (GFP, RFP) | Substrate purification and cleavage visualization |

| Proteomic Tools | TAILS workflow reagents, HPG-ALDII polymer [15] | Global substrate identification, cleavage site mapping |

| Structural Biology | Crystallization screens, cryo-EM reagents | Determining caspase-substrate complex structures |

Advanced Considerations: Regulatory Mechanisms

Phosphorylation-Mediated Regulation

Cross-talk between phosphorylation and caspase cleavage represents a crucial regulatory mechanism. Systematic studies demonstrate that phosphorylation can inhibit caspase cleavage even at residues considered outside the classical consensus motif [15]. For example:

- Phosphorylation of Yap1 and Golgin-160 decreases their cleavage by caspases

- Phosphorylation exerts generally inhibitory effects when introduced throughout caspase recognition motifs

- Positive regulation by phosphorylation may occur through ternary structure modulation rather than direct effects on the cleavage site

Structural Basis of Dual-Site Engagement

The molecular mechanism of caspase-substrate recognition extends beyond simple active site binding. Structural studies of caspase-1 bound to full-length gasdermin D reveal a dual-interface engagement strategy [12]:

- Active site interface: Engages the GSDMD N- and C-domain linker containing the cleavage sequence

- Exosite interface: Formed by caspase-1 L2 and L2' loops binding a hydrophobic pocket in the GSDMD C-terminal domain

- Functional significance: Both interfaces contribute to enzyme-substrate engagement and physiological function in pyroptosis

This dual-interface mechanism likely extends to other physiological caspase substrates and represents an important consideration when investigating cleavage specificity.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do I observe unexpected cleavage products in my caspase-3 assay? A1: Unexpected cleavage is often due to the overlapping substrate specificity of effector caspases. While caspase-3 prefers the DEXD motif, it can also cleave at sites with high similarity, which are preferred by caspases-6 and -7. This overlap means that even in assays designed for a specific caspase, you may see cleavage of "off-target" substrates. Furthermore, initiator caspases like caspase-8 can activate these effector caspases, leading to a cascade of cleavage events in cell-based assays [4] [18].

Q2: How can I confirm that a specific protein is a direct substrate of a particular caspase in a cellular context? A2: Confirming a direct substrate is challenging due to the protease cascade. A recommended approach is to combine multiple methods:

- In vitro cleavage: Use recombinant protein and the caspase of interest to confirm direct cleavage.

- Cell-based validation: Use caspase-specific inhibitors (e.g., Z-VAD-FMK for pan-caspase inhibition) or, more effectively, CRISPR/Cas9 to knock out specific caspases and observe if cleavage is abolished.

- N-terminomics: Employ techniques like subtiligase-mediated N-terminal labeling to globally identify and quantify caspase cleavage events, which can distinguish direct substrates and provide kinetic data [19] [20].

Q3: What are the key sequence motifs that differentiate caspase-3 and caspase-6 substrates? A3: Caspase-3 has a strong preference for Asp (D) at the P4 position (forming the DEXD motif), while caspase-6 prefers Val (V) or Leu (L) at P4 (forming the (V/L)EXD motif). The P2 position is also critical; caspase-3 favors Val, whereas caspase-6 has a broader tolerance [20] [18]. However, significant overlap exists, and contextual factors in the full-length protein can influence cleavage.

Q4: My research focuses on granzyme B-mediated apoptosis. Could caspase substrates be confounding my results? A4: Yes. Granzyme B and several caspases (particularly caspase-3) share a primary specificity for cleavage after Asp. While Granzyme B prefers IEPD, there is an overlap in substrate pools, notably in proteins like Bid, PARP-1, and ICAD/DFF45. It is essential to use specific inhibitors and design substrates with the distinct optimal motifs to disentangle their activities [18].

Troubleshooting Guide: Nonspecific Cleavage

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpected cleavage bands in western blot | Overlap in effector caspase (3, 6, 7) substrate recognition; Residual initiator caspase (8, 9) activity in lysates. | Validate with caspase-specific inhibitors (e.g., DEVD-CHO for caspase-3/7, VEID-CHO for caspase-6); Use activated recombinant caspases in controlled in vitro assays. |

| High background in fluorogenic substrate assay | Contamination from other cellular proteases (e.g., granzyme B, calpains); Sub-optimal inhibitor specificity. | Include broad-spectrum protease inhibitor cocktails; Titrate caspase-specific inhibitor concentrations; Use a more specific, optimized substrate sequence. |

| Discrepancy between in vitro and cellular cleavage data | Competing cleavage by other caspases in cells; Substrate inaccessibility or localization; Post-translational modifications blocking site. | Knockdown/knockout specific caspases in cell models; Perform immunofluorescence to check co-localization; Check for phosphorylation near cleavage site. |

| Poor prediction of cleavage sites via software | Over-reliance on a single prediction algorithm; Algorithm may not account for tertiary structure. | Use multiple prediction tools (e.g., GraBCas, PeptideCutter); Manually inspect sequences for known motif patterns; Confirm experimentally [21] [18]. |

Table 1: Primary Substrate Specificity of Human Caspases

This table outlines the canonical cleavage motifs and group classifications for major caspases, highlighting the basis for substrate overlap [20] [18].

| Caspase | Type | Preferred Tetrapeptide Motif (P4-P1) | Group Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caspase-2 | Initiator/Effector | DEHD | Group II (DEXD) |

| Caspase-3 | Executioner | DEVD | Group II (DEXD) |

| Caspase-6 | Executioner | VEHD | Group III ((L/V)EXD) |

| Caspase-7 | Executioner | DEVD | Group II (DEXD) |

| Caspase-8 | Initiator | LETD | Group III ((L/V)EXD) |

| Caspase-9 | Initiator | LEHD | Group III ((L/V)EXD) |

| Caspase-1 | Inflammatory | WEHD | Group I ((W/L)EHD) |

| Granzyme B | Serine Protease | IEPD | N/A |

Table 2: Documented Shared Substrates and Key Cleavage Events

This table provides examples of proteins cleaved by multiple caspases, illustrating the practical challenge of substrate overlap [4] [22] [3].

| Substrate Protein | Functional Consequence of Cleavage | Documented Cleaving Caspases | Key Cleavage Site(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PARP-1 | Inactivation; prevents DNA repair energy depletion | Caspase-3, -7, Granzyme B | DEVD↑G (214) |

| Bid | Activation; generates pro-apoptotic fragment (tBid) | Caspase-3, -8, Granzyme B | LETD↑S (59), IETD↑S (75) |

| iCAD/DFF45 | Activation of CAD nuclease; DNA fragmentation | Caspase-3, -7 | DETD↑S (117), DAVD↑S (224) |

| Lamin A/C | Nuclear envelope breakdown | Caspase-6 | VEID↑N (230) |

| Gelsolin | Actin depolymerization; membrane blebbing | Caspase-3 | DQTD↓G (403) |

| β-Catenin | Loss of cell adhesion | Caspase-3 | Multiple sites including SYLD↓S (32) |

Caspase Activation and Substrate Overlap Pathway

Experimental Protocols for Deconvoluting Caspase Activity

Protocol 1: Differentiating Caspase Activity Using Fluorogenic Substrates

Principle: Synthetic tetrapeptides conjugated to a fluorophore (like AFC or AMC) are used to selectively monitor the activity of specific caspases based on their motif preferences [20].

Procedure:

- Prepare Reaction Mix: In a 96-well plate, add 50 µL of caspase assay buffer, 10 µL of cell lysate (or recombinant caspase), and 10 µL of the fluorogenic substrate (e.g., Ac-DEVD-AFC for caspase-3/7, Ac-VEID-AFC for caspase-6, Ac-LEHD-AFC for caspase-9). Final substrate concentration is typically 50-200 µM.

- Include Controls: Set up negative controls with lysate from non-apoptotic cells and a blank with buffer only. Include a positive control with a known caspase activator (e.g., staurosporine-treated cell lysate).

- Inhibition Assay: To confirm specificity, pre-incubate experimental samples with 10 µM of the corresponding aldehyde inhibitor (e.g., DEVD-CHO for caspase-3) for 30 minutes before adding the substrate.

- Measure Fluorescence: Read the plate immediately using a fluorescence microplate reader (excitation ~400 nm, emission ~505 nm). Take readings every 5-10 minutes for 1-2 hours at 37°C.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the rate of fluorescence increase (slope) for each sample. Specific activity is determined by subtracting the rate observed in inhibitor-treated samples from the untreated samples.

Protocol 2: N-terminomics for Global Substrate Identification

Principle: This proteomics-based method uses enzyme-mediated labeling of N-terminal α-amines to enrich for and identify neo-N-termini generated by caspase cleavage, providing an unbiased view of the substrate landscape [19].

Procedure:

- Induce Apoptosis: Treat cells (e.g., Jurkat, DB) with an apoptotic stimulus (e.g., 1 µM staurosporine, 10 µM bortezomib) and harvest at various time points (e.g., 0, 2, 4, 8 hours).

- Lyse and Label: Lyse cells and use the enzyme subtiligase to biotinylate free N-terminal α-amines of proteins. This labels the neo-N-termini created by caspase cleavage while ignoring naturally acetylated N-termini.

- Enrich and Digest: Capture biotinylated peptides with streptavidin beads, wash thoroughly, and then release the peptides by acid cleavage. Digest the peptide mixture with trypsin.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Analyze the peptides by liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

- Data Processing: Use bioinformatics tools to identify the sequences of the labeled peptides, which represent the exact cleavage sites. Quantify the abundance of these peptides over time to establish cleavage kinetics.

N-terminomics Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorogenic Substrates (e.g., Ac-DEVD-AFC) | Selective measurement of caspase activity in lysates and live cells. | High specificity for caspase-3/7, but cross-reactivity can occur at high concentrations. |

| Aldehyde Inhibitors (e.g., Z-VAD-FMK, DEVD-CHO) | Irreversible (FMK) or reversible (CHO) inhibition to confirm caspase-dependent events. | Z-VAD-FMK is a broad pan-caspase inhibitor; CHO-based inhibitors are more reversible and specific. |

| Positional Scanning Substrate Combinatorial Libraries (PS-SCL) | Defines the inherent subsite preference and optimal cleavage motif for a caspase. | An in vitro tool for biochemical characterization, not for use in cellular assays [20]. |

| Active Recombinant Caspases | Positive control for in vitro cleavage assays; used to confirm direct substrate cleavage. | Verify activity and absence of contaminants before use in critical experiments. |

| GraBCas Prediction Tool | Score-based bioinformatics prediction of potential cleavage sites for caspases 1-9 and Granzyme B in a protein sequence [18]. | A useful first pass, but predictions must be validated experimentally due to the influence of protein context. |

FAQs: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: My caspase assay is showing cleavage events that do not occur after aspartate. Is this normal, or does it indicate a problem with my enzyme specificity?

Yes, this can be a normal and validated finding. Although caspases were originally defined by their ability to cleave after aspartate (P1 position), modern proteomic studies reveal they also cleave after glutamate and, in the case of caspase-3, after phosphoserine [23]. The collective term "cacidase" has been proposed to reflect this broader specificity for acidic residues [23]. To troubleshoot:

- Verify your findings: Check if the non-aspartate cleavage site conforms to the broader caspase consensus motif (e.g., DEVD↓ for caspase-3, where ↓ is the cleavage site). Glutamate cleavage exhibits virtually identical consensus patterns and similar catalytic efficiency (only ~2-fold slower for DEVE↓ vs. DEVD↓ for caspases-3 and -7) [23].

- Check for phosphorylation: If cleavage occurs after a serine residue, investigate if it is a known phosphorylation site, as caspase-3 cleaves DEVpS↓ (where pS is phosphoserine) at a rate only threefold slower than DEVD↓ [23].

Q2: Why does the cleavage efficiency of my substrate vary significantly between different experimental setups or cell lines?

Variability in cleavage efficiency can be caused by cross-talk with other post-translational modifications, particularly phosphorylation. Phosphorylation near the caspase cleavage site can either inhibit or promote proteolysis [15].

- Inhibitory Effect: Phosphorylation at residues P4, P2, and P1' has been shown to block caspase cleavage. For example, phosphorylation of Yap1 and Golgin-160 decreases their cleavage [15].

- Promotive Effect: In some cases, phosphorylation can promote cleavage, as observed with MST3 in cell lysates, though this may be due to tertiary structural changes rather than direct effects on the scissile bond [15].

- Troubleshooting Step: Review the sequence surrounding your cleavage site for known phosphorylation motifs. Treating lysates with λ-phosphatase prior to the cleavage assay can help determine if phosphorylation is a contributing factor [15].

Q3: I am studying inflammatory models. Do inflammatory caspases exhibit the same promiscuity as apoptotic caspases?

Current evidence suggests that inflammatory caspases have a much narrower substrate range compared to apoptotic executioners. A proteomic screen identified 82 putative substrates for caspase-1, but only three for caspase-4 and none for caspase-5 under similar in vitro conditions [24]. Furthermore, the substrate profile activated in cells by inflammatory stimuli (like monosodium urate or LPS+ATP) is more restricted, highlighting the importance of cellular localization and context in regulating inflammatory caspase activity [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Unexpected Cleavage Events

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Experimental Verification Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Cleavage after Glutamate (E) | Normal, broader specificity of caspases (cacidase activity) [23] | 1. Confirm the site with mutagenesis (E to A).2. Compare kinetics to a known aspartate-site substrate. |

| Cleavage after Serine (S) | Potential cleavage dependent on serine phosphorylation by caspase-3 [23] | 1. Check databases for known phosphorylation at that serine.2. Use phosphomimetic (S to D/E) and phospho-null (S to A) mutants. |

| Variable Cleavage Efficiency | Modulation by proximal phosphorylation [15] | 1. Perform in vitro cleavage assays with and without phosphatase pre-treatment.2. Map phosphorylation sites via mass spectrometry. |

| Poor Cleavage of a Putative Substrate | The protein may not be a bona fide caspase substrate, or the cleavage is context-dependent. | 1. Use multiple caspase concentrations (e.g., 50 nM, 500 nM, 5000 nM) to test for cleavage at high enzyme levels [15].2. Validate cleavage in a cellular model of apoptosis. |

Guide 2: Optimizing Assays to Detect Atypical Cleavage

| Protocol Step | Standard Approach | Optimization for Atypical Cleavage | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate Identification | Focus on proteins with canonical D↓ sites. | Use unbiased N-terminomic techniques like TAILS (Terminal Amine Isotopic Labeling of Substrates) or subtiligase-based labeling [23] [15]. | These global proteomic methods agnostically identify all neo-N-termini generated by proteolysis, revealing non-aspartate cleavages [4]. |

| Kinetic Analysis | Use synthetic peptides with D at P1. | Include matched peptide libraries with D, E, and pS at the P1 position [23]. | Directly quantifies the catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) for non-aspartate residues, confirming their relevance. |

| Cellular Validation | Induce apoptosis and monitor D↓ cleavage. | Analyze cleavage events in both apoptotic and healthy cells to calculate fold-enrichment for each P1 residue (see Table 1 below) [23]. | Establishes the biological significance of non-aspartate cuts during cell death. |

Data Presentation: Quantitative Analysis of Atypical Cleavage

This table, derived from the DegraBase resource (http://wellslab.ucsf.edu/degrabase/), ranks the 20 amino acids by their enrichment as the P1 residue in apoptotic samples compared to healthy cells. It highlights that aspartate, glutamate, and serine are the most enriched residues during apoptosis.

| P1 Residue | % in Apoptotic Cells | % in Healthy Cells | Fold Enrichment (Apoptotic/Healthy) |

|---|---|---|---|

| D (Aspartate) | 24.41% | 6.53% | 3.74 |

| E (Glutamate) | 3.62% | 1.17% | 3.10 |

| T (Threonine) | 2.95% | 1.59% | 1.86 |

| P (Proline) | 2.85% | 1.63% | 1.74 |

| G (Glycine) | 5.41% | 3.50% | 1.55 |

| S (Serine) | 5.52% | 3.59% | 1.54 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| K (Lysine) | 9.43% | 21.41% | 0.44 |

This table summarizes the relative cleavage rates of caspase-3 for its canonical and atypical P1 residues, demonstrating that cleavage after glutamate and phosphoserine is efficient.

| P1 Residue | Peptide Substrate Motif | Relative Cleavage Rate (vs. DEVD↓) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| D (Aspartate) | DEVD↓ | 1.0 (Reference) | Canonical, high-efficiency cleavage. |

| E (Glutamate) | DEVE↓ | ~0.5 (Only 2-fold slower) | Well within the natural 500-fold range of cleavage rates for cellular proteins [23]. |

| pS (Phosphoserine) | DEVpS↓ | ~0.33 (3-fold slower) | Caspase-3 specific; the unphosphorylated serine peptide is not cleaved [23]. |

Experimental Protocols

Purpose: To globally identify protein N-termini and caspase-generated neo-N-termini in a complex cellular lysate, enabling the discovery of cleavage events after aspartate, glutamate, and other residues.

Key Reagents:

- Cell Lysate: Prepared in caspase assay buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

- Phosphatase: λ phosphatase.

- Active Caspases: Recombinant caspase-3 and -7.

- Caspase Inhibitor: z-VAD-fmk.

- Dimethyl Labeling Reagents: NaBH3CN, 12CH2O (light) and 13CD2O (heavy).

- Trypsin: For proteolytic digestion.

- HPG-ALDII Polymer: For negative selection of internal tryptic peptides.

Methodology:

- Caspase Degradome Preparation: Treat clarified cell lysates with or without λ phosphatase. Then, activate cleavage by adding caspase-3/7. Terminate the reaction with z-VAD-fmk.

- Primary Amine Labeling: Reduce and alkylate cysteine residues. Block primary amines (protein N-termini and lysine side chains) by dimethylation with light or heavy formaldehyde labels.

- Trypsin Digestion and Negative Selection: Digest the pooled protein samples with trypsin. React the resulting peptide mixture with the HPG-ALDII polymer, which covalently binds and allows for the removal of internal tryptic peptides (which have α- amines from lysine).

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: The flow-through, enriched for original N-terminal and caspase-generated neo-N-terminal peptides, is analyzed by LC-MS/MS to identify the protein and the precise cleavage site.

Purpose: To determine if phosphorylation at a specific site modulates caspase-mediated cleavage of a substrate.

Key Reagents:

- Substrate: Protein or peptide containing the putative cleavage site and phosphorylation site.

- Kinase/Phosphatase: Specific kinase or λ phosphatase to manipulate the phosphorylation state.

- Active Caspase: Recombinant caspase of interest.

Methodology:

- Prepare Phospho-forms: Generate phosphorylated and dephosphorylated versions of your substrate (protein or synthetic peptide). For proteins, this can be done in cell lysates by using okadaic acid treatment (to inhibit phosphatases) or by direct incubation with λ phosphatase.

- In Vitro Cleavage Assay: Incubate the different substrate forms with a range of caspase concentrations (e.g., 50 nM, 500 nM, 5000 nM) for a set time.

- Analysis:

- For proteins: Analyze cleavage by Western blot, looking for a shift in the protective effect of phosphorylation even at high caspase concentrations.

- For peptides: Use HPLC or MS to quantify the formation of the cleaved product and determine kinetic parameters.

Pathway and Workflow Visualization

Caspase Substrate Cleavage Specificity

Experimental Workflow for Atypical Cleavage Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Atypical Caspase Cleavage

| Reagent | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Caspases (e.g., -3, -7) | In vitro cleavage assays to define enzyme specificity directly. | Use high-purity, active enzymes for kinetic studies. Be aware that caspase-3, but not -7, cleaves after phosphoserine [23]. |

| Pan-Caspase Inhibitor (z-VAD-fmk) | To terminate caspase reactions and confirm caspase-dependent cleavage. | A critical control to ensure observed cleavage is not due to other proteases [15]. |

| λ Phosphatase | To dephosphorylate proteins in cell lysates prior to cleavage assays. | Allows investigation of how phosphorylation status affects cleavage efficiency [15]. |

| Synthetic Peptide Substrates | For quantitative kinetic analysis of cleavage specificity. | Should include variants with D, E, and pS at the P1 position to measure relative rates [23]. |

| HPG-ALDII Polymer | For TAILS workflow; enables negative selection and enrichment of N-terminal peptides for mass spectrometry. | Key for unbiased, global mapping of cleavage events [15]. |

| Okadaic Acid | A phosphatase inhibitor used to preserve the native phosphoproteome in cells. | Helps maintain in vivo phosphorylation states during initial degradome preparation [15]. |

The Impact of Post-Translational Modifications on Cleavage Efficiency

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My caspase assay is showing unexpected cleavage bands. Could post-translational modifications (PTMs) on my substrate be the cause? Yes, PTMs on your substrate are a likely cause. PTMs such as phosphorylation, S-nitrosylation, or ubiquitination can directly alter a protein's structure and obscure or expose the caspase cleavage site, thereby significantly increasing or decreasing cleavage efficiency [25] [26]. For instance, phosphorylation of a serine residue near the cleavage site can inhibit cleavage by caspases [26].

Q2: Which specific PTMs most commonly affect caspase cleavage? The PTMs most frequently reported to impact caspase activity and substrate cleavage are:

- Phosphorylation: This is a key reversible modification that can directly block the caspase cleavage site if the modified residue is near the scissile bond [26].

- S-nitrosylation: This reversible modification of cysteine residues can inhibit caspase activity. Caspases themselves can be stored as inactive S-nitrosylated forms in the cell, and their activation requires denitrosylation [25].

- Ubiquitination: The addition of ubiquitin chains typically targets proteins for degradation by the proteasome. This can regulate the steady-state levels of both caspases and their substrates, indirectly affecting cleavage efficiency [25].

Q3: How can I experimentally test if a specific PTM is affecting caspase cleavage? A standard method involves mutating the putative modification site to a residue that can no longer be modified [26]. For example:

- To prevent phosphorylation, mutate Serine (S) or Threonine (T) to Alanine (A).

- To mimic constitutive phosphorylation, mutate S/T to Aspartic acid (D) or Glutamic acid (E). Subsequently, compare the cleavage efficiency of the wild-type and mutant substrates by caspases in an in vitro cleavage assay [26].

Q4: Are there computational tools to predict if a PTM might affect a caspase cleavage site? Yes, tools like PROSPERous are designed for the rapid in silico prediction of protease-specific cleavage sites [27]. While primarily used to identify cleavage sites based on amino acid sequence, the prediction output can be analyzed in the context of known PTM sites to hypothesize potential interference.

Q5: Why does my recombinant substrate get cleaved by caspases in a purified system, but not in the cellular context? In a purified system, the substrate is devoid of its native PTMs. In cells, the substrate may be modified by inhibitory PTMs (like phosphorylation on a residue near the cleavage site) that prevent caspase access [26]. Alternatively, the cellular environment may contain competitive substrates or endogenous caspase inhibitors that are absent in the purified assay.

Troubleshooting Guide: Nonspecific Cleavage in Caspase Assays

| Problem Area | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate Purity & Design | Substrate preparation contains contaminating proteases or is natively modified. | Use recombinantly expressed and highly purified substrates for in vitro assays. For cellular studies, validate PTM status via mass spectrometry. | [26] |

| Caspase Specificity | Using a caspase concentration that is too high, leading to cleavage at non-physiological, secondary sites. | Titrate the caspase concentration to the lowest level that yields efficient cleavage at the primary site. Refer to established kinetic profiles. | [14] [4] |

| PTM Interference | PTMs (e.g., phosphorylation) on or near the canonical cleavage site sterically hinder caspase access. | Employ site-directed mutagenesis (e.g., S→A to prevent phosphorylation) to create PTM-deficient variants and test their cleavage efficiency. | [26] |

| Recognition Motif | The chosen substrate sequence matches the optimal motif for a different, more abundant caspase in your system. | Verify the specificity of your substrate. Caspase-3 and -7 prefer DEVD, while caspase-8 prefers IETD [14]. Use selective inhibitors to confirm which caspase is responsible. | [14] [4] |

| Experimental Conditions | Non-physiological buffer conditions (pH, salt) alter caspase specificity or substrate folding. | Ensure assay buffers are optimized for the specific caspase being used. Include positive and negative control substrates. | [14] |

Caspase Substrate Reference and PTM Impact Table

The following table summarizes key caspase substrates and examples of how their cleavage and function are regulated by PTMs, based on established scientific literature.

| Substrate | Primary Cleavage Site (P4-P1) | Physiological Role | Consequence of Cleavage | Documented PTM Interference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bid | LQTD (59) | Apoptosis activator | Activated (generates pro-apoptotic fragment) | Phosphorylation: Inhibits cleavage, acting as a molecular switch to regulate cell death [22]. |

| Caspase-6 | VEVD | Apoptosis executioner | Activated | Mutation (R259H): A cancer-associated point mutation causes conformational changes that reduce catalytic efficiency, demonstrating how structural changes mimic PTM effects [26]. |

| Caspase-8 | IETD | Apoptosis initiator | Activated | Mutation (G325A): A mutation identified in head and neck cancer inhibits caspase-8 activity, highlighting critical residues for function [26]. |

| Procaspases | XXXD | Caspase zymogens | Activated (proteolytic processing) | S-nitrosylation: Reversible inhibition; caspases are stored inactivated in mitochondria and activated upon denitrosylation [25]. |

| ICAD | DEMD | DNase inhibitor | Inactivated (activates CAD nuclease) | While not a PTM on the substrate, this is a key example of regulated cleavage: cleavage of ICAD activates its bound partner, CAD. |

| Bcl-2 | DAGD (34) | Apoptosis inhibitor | Inactivated (can generate pro-apoptotic fragment) | Cleavage itself can be seen as an activating PTM that converts an anti-apoptotic protein into a pro-apoptotic one [22] [28]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing the Impact of a PTM via Site-Directed Mutagenesis and In Vitro Cleavage

This protocol is used to determine if a PTM at a specific residue modulates caspase cleavage.

Methodology:

- Modeling: Based on the protein's crystal structure (from PDB), use molecular dynamics (MD) simulation packages (e.g., Amber) to model the wild-type and the mutated form of the caspase substrate. This provides insight into potential structural changes introduced by the mutation [26].

- Mutagenesis: Using site-directed mutagenesis, create mutant constructs of your substrate:

- PTM-deficient mutant: Replace the modifiable residue (e.g., Serine) with Alanine (S→A).

- PTM-mimetic mutant: To mimic a permanent modification, replace Serine with Aspartic acid (S→D) to mimic phosphorylation [26].

- Protein Expression & Purification: Express and purify the wild-type and mutant substrate proteins from a suitable system (e.g., E. coli).

- In Vitro Cleavage Assay: Incubate a fixed amount of each substrate protein with a titrated amount of the active caspase. Run the reaction products on an SDS-PAGE gel and visualize with Coomassie blue or western blotting to compare cleavage efficiency.

Protocol 2: Global Identification of Caspase Substrates and Their Modifications Using N-Terminal Enrichment and Mass Spectrometry

This proteomic approach identifies native caspase substrates and their cleavage sites in a cellular context, which can be correlated with PTM databases.

Methodology:

- Induce Apoptosis: Trigger apoptosis in your cell line of interest (e.g., via Fas ligand, staurosporine).

- Generate Cell Lysates: Prepare lysates from apoptotic and control healthy cells.

- N-terminal Enrichment: Use a positive enrichment strategy (e.g., Negative Sort or Charge-based Fractionation) to selectively isolate and label the new, caspase-generated N-termini [14].

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Digest the enriched protein fragments with trypsin.

- Analyze the resulting peptides using Liquid Chromatography-tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

- Use database search algorithms to identify the protein and the precise cleavage site (P1 aspartate).

- Data Integration: Cross-reference the identified cleavage sites with PTM databases (e.g., RESID, PSI-MOD) to find known modifications near the cleavage site that may regulate efficiency [29].

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and tools for studying caspase-PTM interactions.

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|

| PROSPERous | A computational tool for rapid in silico prediction of protease-specific cleavage sites in substrate sequences, useful for hypothesis generation before wet-lab experiments [27]. |

| Selective Caspase Inhibitors (e.g., Z-VAD-FMK) | Pan-caspase inhibitors used as negative controls in cleavage assays to confirm that observed cleavage is caspase-specific. |

| Phospho-specific Antibodies | Antibodies that detect proteins phosphorylated at specific residues; used to monitor the phosphorylation status of a substrate and correlate it with cleavage efficiency [25]. |

| Amber Molecular Dynamics Package | Software for biomolecular simulation and MD, allowing researchers to model the dynamic evolution of caspase structure and the impact of mutations or PTMs [26]. |

| N-terminal Enrichment Kits (e.g., TAILS) | Commercial kits designed to positively enrich for protein N-terminal, facilitating the identification of protease cleavage sites by mass spectrometry [14]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Commercial kits used to generate specific point mutations in substrate genes (e.g., S→A, K→R) to test the functional role of PTM sites [26]. |

Advanced Methodologies for Detecting and Characterizing Caspase Cleavage

Caspases, a family of cysteine-dependent proteases, are crucial regulators of programmed cell death (apoptosis) and inflammation [30]. These enzymes cleave cellular proteins after aspartic acid residues, orchestrating the controlled dismantling of the cell [3]. Research into caspase activity is fundamental to understanding cancer biology, neurodegenerative diseases, and therapeutic development [30]. The detection of caspase activation serves as a key indicator of apoptosis, making reliable measurement methods essential for researchers in cell biology, pharmacology, and drug discovery [30]. Traditionally, antibody-based methods have been the cornerstone of caspase detection. However, technological advancements have introduced sophisticated live-cell imaging techniques that provide dynamic, real-time insights into caspase activity within living cells [30] [31]. This article explores both classical and cutting-edge methodologies, providing a technical support framework to help scientists navigate the challenges associated with these approaches, particularly focusing on the critical issue of troubleshooting nonspecific cleavage in caspase substrates.

Understanding Caspase Biology and Specificity

Caspase Classification and Activation Pathways

Caspases are typically synthesized as inactive zymogens (procaspases) and undergo proteolytic activation during apoptotic signaling [30]. They are broadly categorized by function:

- Initiator Caspases (e.g., Caspase-2, -8, -9, -10): Activate the apoptotic signal.

- Executioner Caspases (e.g., Caspase-3, -6, -7): Carry out the apoptotic program by cleaving hundreds of cellular substrates.

- Inflammatory Caspases (e.g., Caspase-1, -4, -5, -11): Primarily involved in inflammatory responses [30] [3].

Activation occurs primarily through two pathways:

- The Extrinsic Pathway: Triggered by external death signals via cell surface receptors (e.g., Fas, TNF receptors), leading to activation of caspase-8 [30].

- The Intrinsic Pathway: Initiated by internal cellular stress signals, resulting in mitochondrial cytochrome c release, formation of the APAF-1/procaspase-9 complex (the apoptosome), and activation of caspase-9 [30].

These pathways converge on the activation of executioner caspases, such as caspase-3, which is considered the primary protease responsible for the final stages of apoptosis [30].

Figure 1: Caspase Activation Pathways in Apoptosis. This diagram illustrates the extrinsic (death receptor) and intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathways that activate initiator and executioner caspases.

The Molecular Basis of Caspase Substrate Specificity

Caspases are endopeptidases that cleave their substrates at discrete sites, typically immediately after an aspartic acid (Asp, D) residue—the source of the "c" and "asp" in their name [3]. Substrate recognition is governed by amino acids in the substrate pocket of the caspase. The nomenclature for these substrate positions is:

- P1: The target amino acid after which the cut occurs (almost always aspartate).

- P1': The amino acid following the cut site.

- P2, P3, P4...: The amino acids preceding P1 [3].

An arginine residue in the caspase's substrate pocket holds the target aspartate in position, enabling the catalytic cysteine-histidine dyad to cleave the peptide bond [3]. While the P1 aspartate is essential, the amino acids at P2-P4 determine specificity for different caspases. For example, executioner caspases-3 and -7 share a preference for the sequence DEVD (Asp-Glu-Val-Asp) [3] [32]. Other caspases have distinct preferences, which is a key consideration for designing specific substrates and troubleshooting nonspecific cleavage [4] [6].

Figure 2: Caspase-Substrate Binding Specificity. This diagram shows how amino acids in the substrate (P4-P1) bind to corresponding pockets (S4-S1) in the caspase enzyme, with cleavage occurring after the P1 aspartate.

Methodological Deep Dive: Classical Antibody-Based Assays

Protocol: Caspase Detection by Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence (IF) is a widely used antibody-based technique that allows for the visualization of caspase activation within the spatial context of individual cells [31].

Materials Required:

- Primary antibody against caspase (e.g., anti-Caspase-3)

- Prepared, fixed cell samples on slides

- Triton X-100 or NP-40

- PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline)

- Blocking buffer (PBS/0.1% Tween 20 + 5% appropriate serum)

- Fluorescently conjugated secondary antibody (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate)

- Mounting medium

- Humidified chamber [31]

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Permeabilization: Incubate fixed samples in PBS/0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 minutes at room temperature.

- Washing: Wash three times in PBS, for 5 minutes each.

- Blocking: Drain the slide and add blocking buffer. Incubate for 1-2 hours in a humidified chamber at room temperature.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Add 100 µL of primary antibody diluted in blocking buffer (e.g., 1:200). Incubate overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber.

- Washing: The next day, wash the slides three times for 10 minutes each in PBS/0.1% Tween 20.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Add 100 µL of fluorescently conjugated secondary antibody diluted in PBS (e.g., 1:500). Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature, protected from light.

- Final Washes: Wash three times in PBS/0.1% Tween 20 for 5 minutes, protected from light.

- Mounting and Imaging: Drain the liquid, mount the slides with an appropriate mounting medium, and observe with a fluorescence microscope [31].

Troubleshooting Guide: Antibody-Based Assays

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Caspase Immunofluorescence

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background Staining | Inadequate blocking or washing; non-specific antibody binding. | Use serum from the secondary antibody host species for blocking; include additional washing steps; use an isotype control to subtract Fc receptor binding [31] [33]. |

| Weak or No Signal | Low antibody concentration; poor antigen preservation; low caspase expression. | Titrate the primary antibody to find the optimal concentration; ensure proper cell fixation; include a positive control to confirm assay validity [31]. |

| Non-Specific Staining | Antibody cross-reactivity; over-fixation. | Validate antibody specificity using appropriate controls; optimize fixation time and conditions [31]. |

| Loss of Epitope | Sample not kept on ice; sample fixed for too long. | Keep samples at 4°C to prevent protease activity; optimize fixation protocol (typically <15 minutes for most cells) [34]. |

Methodological Deep Dive: Cutting-Edge Live-Cell Imaging

The Principle of Live-Cell Imaging for Caspase Activity

Live-cell imaging enables real-time monitoring of caspase activity within living cells, preserving dynamic biological processes. This is often achieved using fluorogenic substrates or genetically encoded biosensors [30] [31]. A common approach involves cell-permeable peptides containing a caspase-specific sequence (e.g., DEVD for caspase-3) linked to a fluorophore (e.g., AFC, 7-amino-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin). In the intact substrate, fluorescence is quenched. Upon cleavage by the active caspase, the fluorophore is released, emitting a fluorescent signal that can be detected and quantified over time using fluorescence microscopy [32]. This allows researchers to track the temporal and spatial dynamics of caspase activation in individual living cells.

Protocol: Best Practices for Successful Live-Cell Imaging

Materials and Instrument Setup:

- Phenol red-free culture media

- Appropriate fluorogenic caspase substrate (e.g., Ac-DEVD-AFC) or caspase biosensor

- Automated live-cell imaging system with environmental control (temperature, CO₂, humidity)

- High NA objectives

- Black-walled, clear-bottom imaging microplates [35]

Step-by-Step Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Plate cells in phenol red-free media to reduce background autofluorescence. For suspension cells, use appropriate imaging chambers.

- Environmental Control: Pre-equilibrate the imaging chamber to maintain optimal conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂, and humidity) to prevent focus drift and maintain cell health.

- Substrate Addition: Add the cell-permeable fluorogenic caspase substrate to the cells according to the manufacturer's instructions. Include controls (e.g., untreated cells, caspase inhibitor-treated cells).

- Image Acquisition Setup:

- Autofocus: Use a combination of hardware and software autofocus to maintain focus over time. For fast kinetics, autofocus can be applied to the first time point only.

- Minimize Phototoxicity: Use the lowest possible light intensity and shortest exposure time that still yields a quality image. Avoid UV light when possible.

- Acquisition Frequency: Set the time interval between image captures based on the kinetics of the biological process under investigation.

- Data Acquisition and Analysis: Run the time-lapse experiment and use image analysis software to quantify fluorescence intensity over time, correlating it with caspase activation [35] [32].

Troubleshooting Guide: Live-Cell Imaging

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Live-Cell Caspase Imaging

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Phototoxicity/Cell Death | Illumination power too high; exposure time too long. | Attenuate light source; reduce exposure time; use brighter, more photostable fluorophores [35]. |

| Focus Drift | Temperature fluctuations; inadequate autofocus. | Allow microplate to thermally equilibrate on the stage; employ robust hardware/software autofocus methods [35]. |

| High Background/ Low Signal-to-Noise | Media autofluorescence; probe concentration too low; nonspecific cleavage. | Use phenol red-free, low-serum media; titrate the substrate for optimal signal; use a caspase inhibitor control to confirm specificity [35] [32]. |

| Poor Cell Health | Evaporation-induced osmolarity changes; incorrect gas levels. | Maintain proper humidity; control CO₂ levels or use HEPES-buffered media for short-term experiments [35]. |

| Nonspecific Fluorescent Signal | Substrate cleavage by off-target proteases; probe design. | Use substrates with enhanced specificity (e.g., 2MP-TbD-AFC shows better caspase-3 selectivity than Ac-DEVD-AFC); validate with caspase-specific inhibitors [32]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Caspase Detection Assays

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Caspase-Specific Antibodies | Detect caspase protein levels and activation (e.g., by IF, Western Blot). | Anti-Caspase-3 [31]. Critical to validate for specific applications. |

| Fluorogenic Caspase Substrates | Measure caspase enzyme activity in live or lysed cells. | Ac-DEVD-AFC (for caspases-3/7); 2MP-TbD-AFC (optimized for caspase-3 specificity and permeability) [32]. |

| Caspase Inhibitors | Confirm caspase-dependent signal; negative controls. | Z-VAD-FMK (pan-caspase inhibitor) [32]. Essential for validating substrate specificity. |

| Live-Cell Imaging Media | Maintain cell health while minimizing background during imaging. | Phenol red-free media, optionally with HEPES buffer [35]. |

| Viability Dyes | Distinguish apoptotic from necrotic cells. | Propidium Iodide (PI), 7-AAD [33]. Used to gate out dead cells in flow cytometry or confirm membrane integrity. |

| Fluorescent Reporters (Biosensors) | Genetically encoded tools for real-time caspase activity monitoring in live cells. | FRET-based caspase sensors [30]. Enable spatial and temporal tracking in live cells. |

FAQs: Addressing Core Technical Challenges

Q1: My caspase substrate shows high background signal in live-cell imaging. How can I determine if this is due to nonspecific cleavage?

A: To confirm specificity, always run parallel control experiments using a broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor such as Z-VAD-FMK. A significant reduction in fluorescent signal upon inhibitor treatment confirms that the signal is caspase-dependent. If the signal persists, it is likely due to nonspecific cleavage by other cellular proteases. In this case, consider using a more specific substrate. For example, the minimized substrate 2MP-TbD-AFC has been shown to have superior caspase-3 selectivity and lower off-target activity compared to the traditional Ac-DEVD-AFC substrate [32].

Q2: In my immunofluorescence experiment, I am getting a weak signal for active caspase-3. What are the primary factors I should check?

A: A weak signal can stem from several sources. First, verify your antibody concentration by performing a titration to find the optimal dilution. Second, ensure your sample fixation and permeabilization protocols are effective, as inadequate permeabilization will prevent antibody access to intracellular caspases. Third, confirm that your apoptosis induction method is robust by including a validated positive control. Finally, check that your fluorophore is bright and stable, and consider using a signal amplification method, such as a biotin-streptavidin system, for low-abundance targets [31] [33].

Q3: For live-cell imaging of caspases, what are the key steps to minimize phototoxicity while still acquiring usable data?

A: Minimizing phototoxicity is critical for maintaining normal cell physiology. Key steps include:

- Attenuate Light: Use the lowest possible intensity from your light source.

- Reduce Exposure Time: Optimize exposure to the shortest duration that provides a sufficient signal-to-noise ratio.

- Choose Fluorophores Wisely: Use bright, photostable fluorophores that can be imaged with low light levels. Red-shifted fluorophores (e.g., Alexa Fluor 647) are generally less phototoxic than UV-excited dyes like DAPI.

- Limit Acquisition Frequency: Collect images at the longest time intervals acceptable for capturing your biological process.

- Use Hardware Autofocus: This is faster and exposes cells to less light than software-based methods [35].

Q4: How can I improve the specificity of a caspase activity assay?

A: Specificity can be enhanced at multiple levels. For substrate-based assays, choose substrates with well-defined specificity profiles. Combinatorial peptide libraries have revealed that even small changes (e.g., Valine to O-benzylthreonine at the P2 position) can dramatically improve selectivity for caspase-3 over caspases-8 and -10 [32]. For antibody-based assays, rigorous validation of antibodies using knockout cell lines or specific inhibitors is essential. In live-cell imaging, using genetically encoded FRET sensors can provide high specificity, as they are based on the precise cleavage of a defined protein linker [30].

Both classical antibody-based assays and cutting-edge live-cell imaging techniques provide powerful, complementary means to investigate caspase activity in biological research. Antibody-based methods like immunofluorescence offer high spatial resolution and are indispensable for endpoint analyses in fixed samples. In contrast, live-cell imaging unveils the dynamic nature of apoptosis in real time, providing unparalleled kinetic data. The choice between them depends on the specific research question, resources, and required throughput. By understanding the principles, optimizing protocols, and systematically troubleshooting common issues—especially those related to substrate specificity—researchers can reliably generate robust data to advance our understanding of cell death in health and disease.

Leveraging Mass Spectrometry and N-terminomic Platforms for Unbiased Substrate Discovery

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges & Solutions

Researchers often encounter specific challenges when using mass spectrometry-based N-terminomics for caspase substrate discovery. The table below outlines common issues, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High background of internal peptides | Incomplete blocking of internal peptides during sample preparation [36] | Optimize acetylation protocol; use fresh reagents; verify pH conditions for blocking reactions [36] [37]. |

| Weak or absent neo-N-terminal peptide signals | Low abundance of substrates; inefficient enrichment [36] | Increase starting material; use positive enrichment methods (e.g., Subtiligase, CHOPS) for direct isolation [36]. |

| Inability to distinguish specific caspase cleavage | Nonspecific proteolysis from other cellular proteases [36] [4] | Use "reverse N-terminomics": quench endogenous proteases before adding protease of interest [36]. |

| Misidentification of modification sites | Isobaric PTMs (e.g., tri-methylation vs. acetylation) [38] | Use high-resolution mass spectrometers (Orbitrap, Q-TOF); employ MS/MS fragmentation to confirm identities [38]. |

| Inability to pinpoint cleaving protease | Overlapping cleavage specificities among caspases and other proteases [4] [20] | Combine with caspase-specific inhibitors or activity-based probes in control experiments [30] [20]. |

| Poor separation of peptides | Suboptimal chromatographic conditions; sample contaminants [37] | Implement high-pH fractionation; desalt samples thoroughly using C18 stage tips [37] [38]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the key differences between "forward" and "reverse" N-terminomics, and when should I use each?

Forward N-terminomics is used for discovery-level profiling of global proteolytic events. You compare control and treated (e.g., apoptotic) cell populations to identify all differential cleavage events [36]. This is ideal for unbiased discovery but does not directly identify which protease is responsible for each cleavage.

Reverse N-terminomics is used to identify specific substrates of a single protease. In this approach, you first quench all endogenous proteolytic activity, then add your purified caspase of interest to the cell lysate. Any new cleavages identified are direct substrates of that caspase [36]. Use this when studying a specific caspase.

My N-terminomics experiment identified hundreds of cleavage sites. How do I prioritize which ones are functionally relevant for caspase signaling?

Prioritization is a major challenge. Use this multi-faceted approach:

- Cleavage Efficiency: Prioritize sites with high cleavage rates, as proteomics studies show cleavage rates can vary by over 500-fold, and more efficient sites are more likely to be functional [4].

- Conservation: Check if the cleavage site and surrounding sequence are evolutionarily conserved.

- Known Domains & Motifs: Determine if the cleavage occurs within a critical functional domain or a known protein-protein interaction motif [4].

- Validation: Always confirm key findings using orthogonal methods (e.g., western blotting with cleavage-specific antibodies or in vitro cleavage assays) [30].

How can I be sure my identified cleavage sites are specific to caspases and not other proteases with similar specificity?

Caspases have a strong preference for cleaving after aspartic acid (Asp, D) residues [4] [20]. While other proteases like Granzyme B also cleave after Asp, you can increase confidence by:

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Check if the cleavage site (P4-P1') matches the optimal recognition motif for your caspase of interest (e.g., DEVD for caspase-3) [20] [39].

- Inhibitor Studies: Repeat the experiment in the presence of a broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor (e.g., Z-VAD-FMK). Cleavages that disappear are likely caspase-specific [30] [20].

- Use of Predictive Tools: Employ bioinformatics tools like CAT3 (for caspase-3) that are trained on confirmed caspase substrates to score your identified sites and reduce false positives [39].

What are the major advantages of N-terminomics over traditional biochemical methods for substrate discovery?

- Unbiased Nature: N-terminomics does not require pre-existing hypotheses about substrate identity, enabling discovery of novel and unexpected substrates [36] [4].

- System-wide Scale: It allows for the identification of hundreds to thousands of cleavage events in a single experiment, providing a systems-level view of proteolysis [36].

- Precision: It identifies the exact amino acid where cleavage occurs, providing precise cleavage site information [36].

- In vivo Relevance: When performed on cell lysates or tissues, it can reveal cleavage events that occur under physiological conditions, preserving native cellular context [36].

Why might a known caspase substrate not be identified in my N-terminomics experiment?

Several factors could lead to false negatives:

- Low Abundance: The substrate or its cleaved fragment may be below the detection limit of your mass spectrometer.

- Rapid Degradation: The neo-N-terminal peptide generated by caspase cleavage might be rapidly degraded by other cellular proteases [36].

- Inefficient Enrichment: The peptide's physicochemical properties (e.g., length, charge) may make it inefficiently enriched or ionized during MS analysis.

- N-terminal Modification: If the protein has a blocked N-terminus (e.g., by acetylation or pyroglutamate formation), it will not be detected by standard Edman-based N-terminomics protocols [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in N-terminomics / Caspase Research |

|---|---|

| TAILS (Terminal Amine Isotopic Labeling of Substrates) | A negative enrichment N-terminomics method that uses dendritic polymers to covalently bind and remove internal tryptic peptides, allowing isolation of native and neo-N-termini [36]. |

| COFRADIC (COmbinalorial FRActional Diagonal Chromatography) | A negative enrichment method that uses diagonal chromatography to induce a chromatographic shift in internal peptides, separating them from N-terminal peptides [36]. |

| Subtiligase | An engineered ligase used in positive enrichment N-terminomics to biotinylate N-terminal peptides, enabling their direct purification [36]. |

| Caspase Inhibitor (Z-VAD-FMK) | A broad-spectrum, cell-permeable irreversible caspase inhibitor. Essential for control experiments to confirm caspase-specific cleavage events [30] [20]. |

| Fluorogenic/Lumigenic Caspase Substrates (e.g., DEVD-AMC, DEVD-aminoluciferin) | Peptide substrates linked to a fluorescent or luminescent reporter. Used to measure caspase activity in cell lysates and validate the proteolytic function of your caspase of interest [20]. |

| CAT3 (Caspase Analysis Tool 3) | A bioinformatics tool that uses a Position-Specific Scoring Matrix (PSSM) to predict caspase-3 cleavage sites in protein sequences with high accuracy (AUC 0.94), helping prioritize potential substrates from proteomic data [39]. |

| Positional Scanning Synthetic Combinatorial Libraries (PS-SCL) | Libraries of tetrapeptide substrates used to define the inherent substrate specificity and optimal cleavage motifs for different caspases (e.g., DEVD for caspase-3) [20]. |

Experimental Workflow: Reverse N-terminomics for Caspase Substrate Identification

Diagram: Reverse N-terminomics workflow for identifying direct caspase substrates. Control and caspase-treated samples are processed in parallel to distinguish specific cleavage events.

Cell Lysis and Quenching:

- Lyse control and apoptotic cells in a denaturing lysis buffer (e.g., 6 M Guanidine HCl) to instantly inactivate all endogenous proteases.

- Reduce and alkylate cysteine residues.

Blocking of Native N-termini:

- Block all primary amines (native protein N-termini and lysine side chains) by acetylation with stable isotope-labeled tags (e.g., light formaldehyde for control, heavy for treated). This allows for relative quantification.

Protease Incubation:

- Divide the pooled, acetylated lysate.

- Add your purified, active caspase of interest to the test sample. The control sample receives buffer only.

- Incubate at a physiological temperature (e.g., 37°C) for a defined time.

Trypsin Digestion:

- Quench the caspase reaction.

- Digest the proteins to peptides with trypsin. This generates internal peptides with free amines and neo-N-terminal peptides from caspase cleavage (which remain blocked).

Enrichment with TAILS:

- Incubate the peptide mixture with a hyperbranched polyglycerol aldehyde polymer.

- The polymer covalently binds to the amines of internal tryptic peptides.

- Remove the polymer-bound internal peptides by ultrafiltration. The flow-through contains the blocked N-terminal peptides (both original and caspase-generated).

Mass Spectrometry and Data Analysis:

- Analyze the enriched N-terminal peptides by LC-MS/MS.

- Use database search engines (e.g., MaxQuant) to identify peptides and their modifications.

- Neo-N-termini generated by caspase cleavage will be identified as N-terminally acetylated peptides that are more abundant in the caspase-treated sample. Bioinformatics tools like CAT3 can then help score and validate these sites as bona fide caspase cleavage events [39].

Caspase Signaling Pathways in Apoptosis

Diagram: Simplified caspase activation pathways. The extrinsic and intrinsic pathways converge on the activation of executioner caspases (e.g., -3, -7), which then cleave a wide array of cellular protein substrates, leading to apoptosis [30] [4].

Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) biosensors and fluorogenic substrates are powerful tools for monitoring biochemical activities, including caspase activity, in live cells. FRET is a distance-dependent, non-radiative energy transfer process from an excited donor fluorophore to a suitable acceptor fluorophore, effective within a range of 1–10 nanometers [40] [41]. This property makes it exceptionally useful for reporting on molecular interactions, conformational changes, and proteolytic events, such as those mediated by caspases during apoptosis.

In the context of your thesis research on troubleshooting nonspecific cleavage in caspase substrates, understanding the fundamental principle is key. The efficiency of FRET (E) is quantitatively described by the following equation, where R is the actual distance between the donor and acceptor, and R₀ is the Förster radius (the distance at which 50% energy transfer occurs) [40] [42]: